From Assessment OF Learning to Assessment FOR Learning

Ali Saukah is a professor at Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. He is a frequent speaker at language conferences in the Asian region and has published extensively in international peer review journals. His research interests include assessment, teacher professional development, and publication writing.

Abstract

This paper reports on findings from an investigation of teachers’ understanding of assessment for learning and how their understanding affects their ways in doing follow up actions. Overall, the findings indicate some gaps between the beliefs and perceptions of the teachers and the classroom practices.

Introduction

Assessment or “any systematic method of obtaining information from tests and other sources, used to draw inferences about characteristics of people, objects, or programs” (Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, published by American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.)., 2014) is an important part of education.

Assessment has been widely used as an instrument to measure the learning outcomes of the students at the end of an educational program (or their proficiency) for promotion from one level to a higher level of education, for graduation decisions, and for certification purposes. It has also been used as an instrument for school or college admissions and other selection purposes. The role of assessment designed to serve such purposes seems to cease right after its purposes have been served. Such assessment can be labelled as assessment of learning.

Assessment is also expected to contribute to collecting information about the strengths and weaknesses of the students to maximize their learning outcomes, as feedback for the teachers to modify teaching and for the students to modify learning. Assessment designed to serve such a purpose has been recognized as formative or diagnostic assessment. Such assessment can be labelled as assessment for learning.

The effect of assessment of learning and assessment for learning can be observed from the following evidence: “Students given marks are likely to see it as a way to compare themselves with others; those given only comments see it as helping them to improve. The latter group outperforms the former.” (Black et al., 2004)

Assessment for Learning: Diagnostic Language Assessment (DLA)

As a subfield of language assessment, Diagnostic Language Assessment (DLA) can be considered as assessment for language learning. Two fundamental goals of DLA are to identify language learners’ weaknesses and deficiencies, as well as their strengths, in the targeted language domains and provide useful diagnostic feedback and guidance for remedial learning and instruction (Lee, 2015a). In other words, DLA seeks to promote further learning designed to address the test-takers’ weaknesses and increase their overall growth potential. Thus, it is important to create meaningful linkages between outcomes of diagnosis and subsequent learning and instruction when designing the DLA system.

According to Lee (2015b), there are three core components of DLA: diagnosis, feedback, and remedial learning. Each is described below.

Diagnosis is the core component of DLA. The central goal of diagnosis in DLA is to identify not only one’s strengths but also weaknesses that prevent the learner from moving beyond the current level of learning (or knowledge, proficiency, ability, or competence) to the next level. Diagnosis requires developing and using various diagnostic instruments (including tests, questionnaires, and tools) and procedures for collecting, analyzing, and scoring the test-takers’ data, estimating the learners’ pattern of strengths and weaknesses in a targeted domain, and, if necessary, classifying the learners into groups of learners with the same (or a similar) pattern of strengths and weaknesses.

Feedback is designed to describe, summarize, and present the results of diagnosis to the learners, teachers, and other stakeholders of assessment in various formats. Once the strengths and weaknesses (along with the root causes of the weaknesses) are identified, such information should be communicated effectively to the learners and teachers, so that they can take necessary or recommended actions to strengthen the identified weaknesses and increase the overall learning potential.

Remedial learning (or treatment/intervention) is a set of learning activities that are designed to help the learners improve on the attributes that were identified to be weak and thereby reach the desired goals of learning and proficiency in the targeted domain of language and communication.

Studies in Diagnostic Language Assessment

There are some studies related to Diagnostic Language Assessment (DLA). Each would be presented below.

Alderson et al. (2015) developed a tentative framework which can be translated into a set of five principles for the diagnosis of strengths and weaknesses in second or foreign language:

- It is not the test which diagnoses, it is the user of the test.

- Instruments themselves should be designed to be user-friendly, targeted, discrete and efficient in order to assist the teacher in making a diagnosis. Diagnostic tests should be suitable for administration in the classroom, designed or assembled by a trained classroom teacher, and should generate rich and detailed feedback for the test-taker. Most importantly, useful testing instruments need to be designed with a specific diagnostic purpose in mind.

- The diagnostic assessment process should include diverse stakeholder views, including learners’ self- assessments.

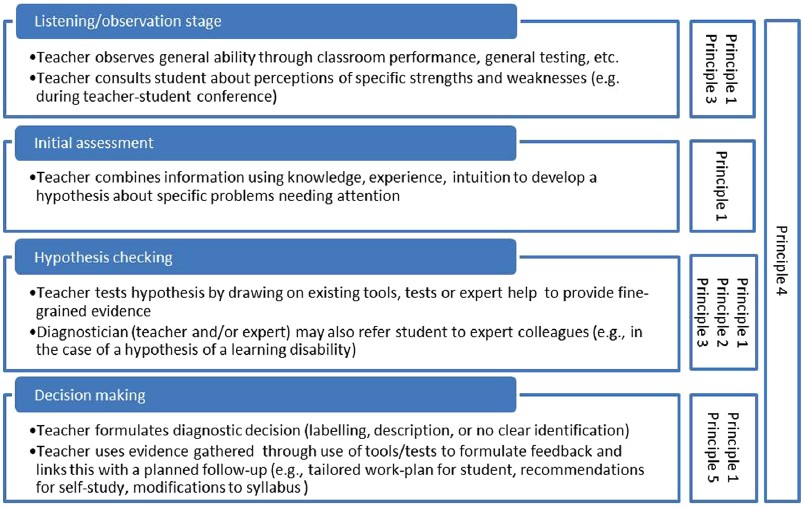

- Diagnostic assessment should ideally be embedded within a system that allows for all four diagnostic stages: (1) listening/observation, (2) initial assessment, (3) use of tools, tests, expert help, and (4) decision-making.

- Diagnostic assessment should relate, if at all possible, to some future treatment.

One of the key practical outcomes of this set of principles is the proposal for an “ideal” diagnostic process in principle 4 which is illustrated and expanded in the figure below.

Note that this four-stage process addresses principles 1, 2, 3 and 5 in its recommendations for: stake-holder involvement (including learners themselves) (principle 3); targeted, purpose built diagnostic tools, selected from a bank according to purpose (principle 2); rich and detailed feedback (principle 2); and treatment or intervention to address specific problems which have been identified (principle 5). All of this is performed by a skilled “diagnostician” 2 (principle 1).

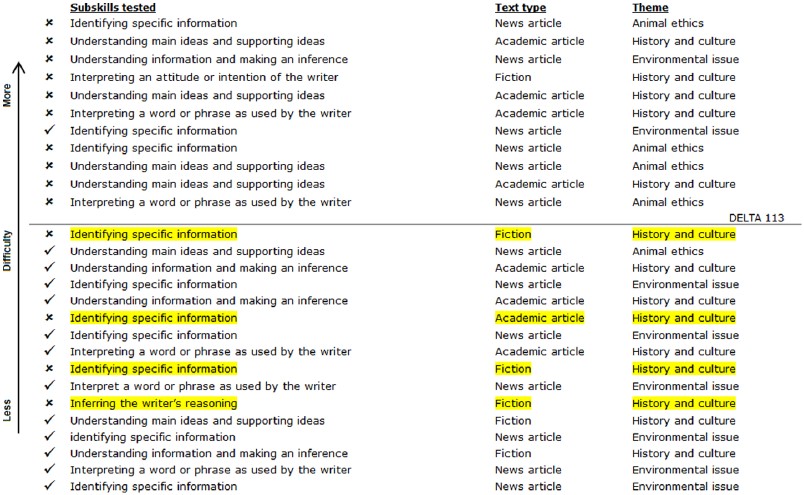

Another example of the development of Diagnostic Language Assessment is of Reading: Diagnostic English Language Tracking Assessment (DELTA) which tests a range of subskills across various text types and addresses a range of different topic areas. The figure below presents the reading subskills tested in DELTA, and gives an example of which subskills a particular learner performed poorly on (indicated with a “x” and highlighted). The diagnostic report is “based on the item difficulty relative to the student’s proficiency. If they are not answered correctly, they indicate possible weakness in that particular subskill” (Urmston, Raquel, & Tsang, 2013, p. 74 in Harding et al. 2015).

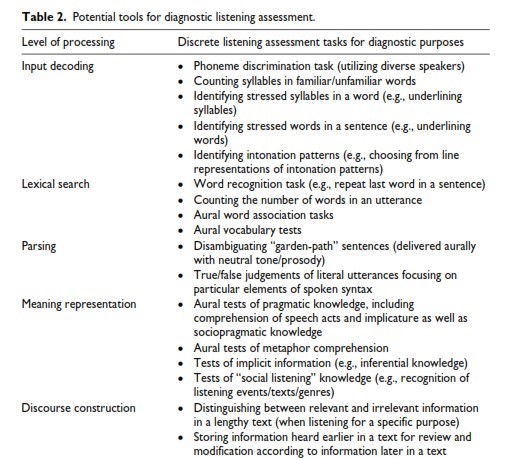

Another example, which is related to listening, is as shown in the table suggested by Harding et al. (2015) below. The table presents a set of diagnostic tools, which take into account the strengths and weaknesses in various linguistic and extra-linguistic knowledge sources that are crucial for meaning-making and for building a structure of a listening event.

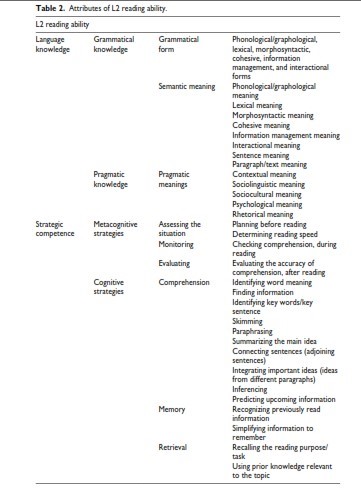

Another study related to reading was done by Kim (2015) in exploring how a placement test score could be used for diagnosing the L2 reading ability of incoming students to an adult ESL program. The list of L2 reading attributes was developed by drawing upon previous literature on language ability models as shown below:

A study on making use of national exam in Indonesia for assessment for learning purposes was conducted by Wulansari & Kumaidi (2015). The study was aimed at finding information around the National Examination on Elementary School Mathematics in the 2012/2013 academic year. The information includes: (1) the underlying attributes of the test items, (2) the materials in the questions that cause many students to make mistakes, (3) types of mistakes made by the students, (4) the location of the dominant student’s misconceptions, and (5) the main cause of the student’s misconceptions. Content analysis was used in descriptive quantitative research. The sources of the data were the student answer sheets and national exam booklet.

All of the previous studies indicated the importance of assessment for learning particularly the Diagnostic Language Assessment (DLA) to improve the quality of the teaching and learning process in the classroom. However, there has not been an in depth study conducted to describe in detail the teachers’ understanding of assessment for learning and how their understanding affects their ways in doing follow up actions.

Methods

A survey involving 108 respondents of lecturers and teachers, mostly in EFL contexts from different parts of Indonesia, is aimed at describing EFL educators’ awareness of assessment for learning. The respondents completed questionnaires distributed through emails to students, ex-students, and their colleagues.

There were some questions raised:

- In addition to using the results of mid-term tests for assigning grades, do you use them for any follow-up actions?

- In addition to using the results of final tests for assigning grades, do you use them for any follow-up actions?

- If you use the results of mid-term tests not only for assigning grades, what kinds of follow-up actions do you do?

- If you use the results of final tests not only for assigning grades, what kinds of follow-up actions do you do?

- Do you analyze the students’ responses to the tests?

- If you do, what kinds of analysis do you do?

- Do you know the difference between “assessment of learning” and “assessment for learning”?

- If you do, describe the difference between “assessment of learning” and “assessment for learning”.

Some questions were written in the closed-ended format; while the others were in open-ended format.

Findings

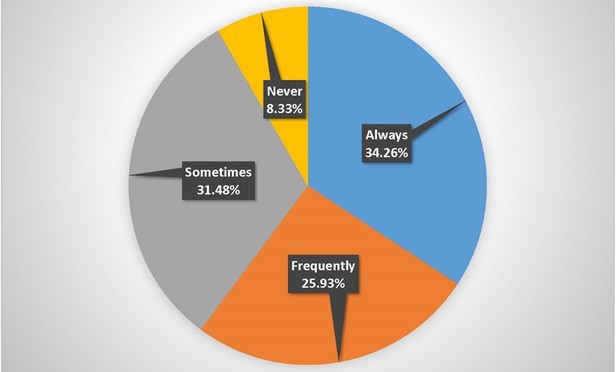

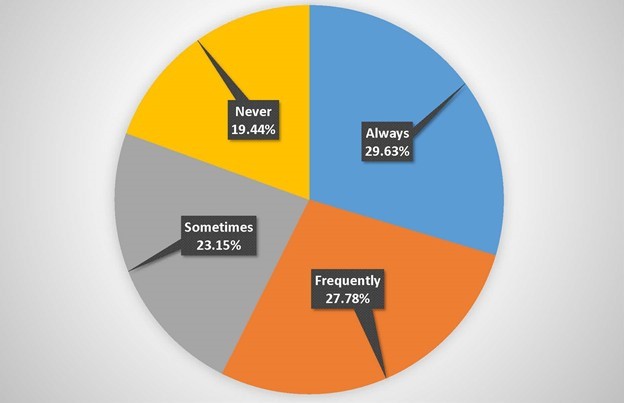

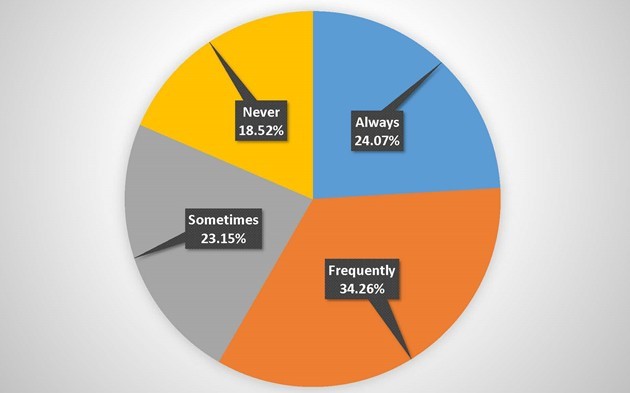

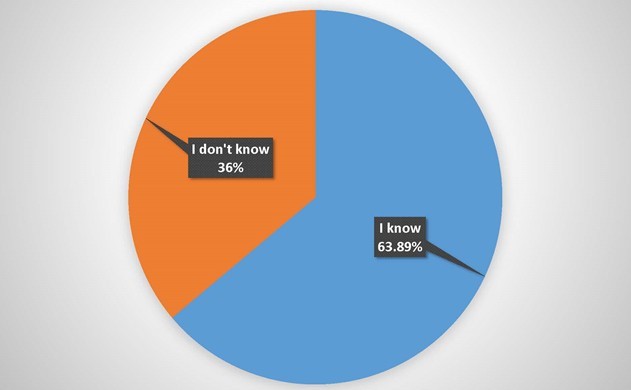

The following apple-pie charts showed the frequency of practices of follow-up actions reported by the respondents and proportions of the respondents who thought they knew or did not know about assessment for learning.

The Frequency of Teachers who Used the Results of Mid-Term Test for Any Follow-up Actions

The Frequency of Teachers who Used the Results of Final-Term Test for Any Follow-up Actions

The Frequency of Teachers who Analyzed Their Students’ Responses to the Tests

The Number of Teachers who Understood the Concept of Assessment for Learning and Assessment of Learning

The open-ended questions were intended to reveal the match between what the respondents reported as implementation of assessment for learning and the operational definitions of assessment for learning, and the match between what they reported as “knowing” and their explanation about “assessment for learning”. The results were as follows:

- The answers of the open-ended questions about follow-up actions of midterm tests were summarized into two different categories considered to be “assessment for learning related follow-up actions” (35%) and “NOT-assessment for learning related follow-up actions” (65%).

- The answers of the open-ended questions about follow-up actions of final tests were summarized into two different categories considered to be “assessment for learning related follow-up actions” (31%) and “NOT-assessment for learning related follow-up actions” (69%).

- The answers of the open-ended questions about conducting test response analysis to implement “assessment for learning” were summarized into two different categories considered to be “assessment for learning related analysis”(22%) and “NOT-assessment for learning related analysis” (78%)

- The answers of the open-ended questions about awareness of “assessment for learning” were summarized to reveal a match between their choice “know” and “what they know about assessment for learning” (50% match).

Discussion

The results of the study showed some interesting findings. First, there was an imbalance between the implementation of assessment of learning and that of assessment for learning. Second, there were gaps between respondents’ perceptions (what they think they do) and practices (what they describe in implementing assessment for learning). There were also gaps between respondents’ beliefs (what they think they know) and knowledge (what they describe about assessment for learning). In that case, a strong linkage must be established among research, policy and practice.

There are, for example, some potential research topics investigating:

- why assessment for learning is imbalance with the assessment of learning,

- how assessment of learning can be combined with assessment for learning,

- how assessment for learning can be effectively integrated into classroom assessment,

- how the results of assessment of learning (achievement and proficiency tests) can be analyzed to promote teaching and learning,

- the effect of assessment for learning on the improvement of the students’ English, and

- how to develop diagnostic language assessment in harmony with the EFL curriculum in Indonesia.

Based on research, curriculum implementation policy should allow and facilitate teachers to implement assessment for learning integrated into teaching and maintain the balance between assessment of learning and assessment for learning. As for classroom practice, teachers are encouraged to implement assessment for learning to promote teaching and learning

Conclusion

There is a need and potential for increasing the role of assessment for learning to improve the quality of education in Indonesia, especially language learning. The overall findings of this research indicate a need for more research in this field and a need for informing teachers about assessment for learning. Such knowledge will influence the teachers’ actions and decisions in their classrooms.

References

Alderson, J. C., Brunfaut, T., & Harding, L. (2015). Towards a theory of diagnosis in second and foreign language assessment: Insights from professional practice across diverse fields. Applied Linguistics, 36 (2), 236–260

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.). (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: AERA.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Assessment for Learning in the Classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 1(86), 8-21.

Harding, L., Alderson, C., & Brunfaut, T. (2015) Diagnostic assessment of reading and listening in a second or foreign language: Elaborating on diagnostic principles. Language Testing, 3(32), 317-336.

Kim, A. (2015). Exploring ways to provide diagnostic feedback with an ESL placement test: Cognitive diagnostic assessment of L2 reading ability. Language Testing, 2(32), 227-258.

Lee, Y.W. (2015a). Future of diagnostic language assessment. Language Testing, 3(32), 295-298.

Lee, Y.W.. (2015b). Diagnosing diagnostic language assessment. Language Testing, 3(32), 299-316.

Wulansari, W, & Kuamidi. (2015). Analisis Kesalahan Konsep Siswa Dalam Menyelesaikan Soal Ujian Nasional Matematika SD. Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan (JIP), 1(21), 97-105.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

From Assessment OF Learning to Assessment FOR Learning

Ali Saukah, Indonesia