Language Policy: The Case of Hong Kong

Ivy Lai Chun is a postgraduate graduate in Hong Kong (with two MAs in CUHK, and a BA in HKU). She is an independent researcher, and simultaneously has been working at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) for more than 5 years as a full-time administrator. Her HKU Scholar Hub page is: http://hub.hku.hk/cris/rp/rp01886. She is currently the Knowledge Exchange Manager at HKU. Her professional research interests in education are language policy, innovation and curriculum design, and applied linguistics. She had presented on “dim sum” vocabulary in the English classroom in an International Applied Linguistics Conference in Tai Wan. Previously, she was a full time English language teaching academic in a sub-degree programme in one of the community colleges in Hong Kong. She had been a teaching assistant or a research assistant in various universities in Hong Kong (namely HKU, CUHK, HKBU). Her strong education background enabled her to apply knowledge into practice at the workplace in a number of education settings. Her official email address is ivylolaicc@hku.hk

Introduction

Language policy has a huge impact on professionalism of language teachers. Language teachers speak of their own stories to articulate issues pertinent to language policy to illuminate the ways in which they professionally respond to language policy. Language policy imposed by the government, as the teachers say, is strongly connected to their professionalism in language teaching.

Literature Review

Global English vs. learning English as a national mission

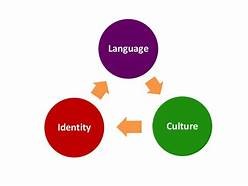

Ever since, there lies in a cross-over of boundary between global and local. While English teachers are greatly influenced by the hegemony of English and globalization when teaching English, in many Asian countries, the states strongly intervene by emphasizing that learning English is known as a 'national mission' (Tsui, p. 4). Learning English in their own nations enables learners to construct and reconstruct their own identities discursively, upon which ideology is based. For example, Hong Kong students are skeptical about the Hong Kong identities by questioning themselves the values of learning English in relation to globalization and hegemony of English, especially for being torn by the British rule in the past and the Mainland Chinese rule at the present. Hong Kong learners are attempting to assert their Hong Kong identities when Hong Kong English gradually emerges. As Amy Tsui puts it, language and cultural identity are 'mutually constitutive' (Tsui, p. 2).

The paradox: preserving national traditions vs. learning global English

In spite of supporting learning English as a national mission, there have been heated debates about how to preserve traditional national interests while promoting to learn global English. 'How do governments in Asian countries resolve the paradox of preserving or building national cultural identities and promoting a foreign language that embodies different values, cultures and traditions?' (Tsui, p. 3) This paradoxical issue has been controversial for long. For example, the mother tongue policy implemented in Hong Kong has, on one hand, encourages the use of mother tongue to boost national education; on the other hand, the incentives to learn English have been hampered that not many elites proficient of English can be produced. The access paradox conveys that student access to global English perpetuates the dominance of the global language English; however, denying student access to global English will be perpetuating their marginalization in society, limiting their life chances (Janks, p. 33). The dominance of global English language permeates in so far as segregation takes place in society, albeit the attention for preserving national traditions is being paid alarmingly. This leads to discussion about the demand for native vs non-native speakers in teaching English.

Non-native speakers (NSS) vs native speakers (NS) as English teachers

There has been a common misconception that native speakers (NS) are more superior than non-native speakers (NNS) as English teachers, which 'has never stopped plaguing NNS professionals in the field of TESOL (Lee and Sze, p. 2).' Phillipson has debunked the notion that a native speaker (NS) is the ideal English teacher and thus names it as 'the native speaker fallacy' (ibid.) The NS versus NSS debate revolves around whether NS or NSS are better English teachers (ibid). While the hegemony of English under the influence of globalization constitutes a belief that NS is essentially in need of English teaching, NSS also plays an important role in teaching English in Outer Circles or Expanding Circles not only by employing bilingualism or code-switching but also by sharing their reflective experience of teaching and learning English. Icy Lee, a NSS teacher who teaches English in Vancouver, outlines the advantages a NSS teacher possesses.

'Because NSS teachers themselves have learned English as a second language (L2) or foreign language, they understand the needs and experience of L2 students better. As L2 learners themselves, they have probably spent a great deal of time and effort trying to master the language. How they learned grammar, how they attempted to expand their vocabulary, and how they overcame the problems they faced during learning are all precious experiences that they can share with students. Their determination to succeed, and the fact that they did succeed, provide an excellent example for L2 students (ibid, p. 17).'

According to Icy Lee, the 'nationality' (i.e. the skin Colorado) or accent does not matter in contributing to being good English teachers (ibid, p. 18). Most importantly, it is the 'drive', the 'motivation' and the 'zeal' within NSS teachers to help their students 'make a difference' that defines their competence (ibid).

The implementation of mother-tongue policy in Hong Kong

Although the NSS teachers could be excellent English teachers, there has been controversy over how many teachers can effectively exercise the use of English in class to facilitate students understand the subject better.

In 1998, a year after the handover of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong government enforced the new language policy to promote the use of mother tongue (CMI) in school. Only were 114 schools allowed to use English as the Medium of Instruction (EMI), given they had satisfied the requirements imposed by the policy. There have been heated debates about having enough teachers and resources in carrying out EMI in these schools. If their requirements had not been met, they would not be permitted to use EMI, and fall into CMI. This is what most parents do not wish to see, as they believe the EMI schools they send their children to provide them with elite education that will give them a more prosperous future. This seems inequitable and socially unjust. According to Phillipson (1992), the hegemony of English offers learners linguistic capital. The spread of English is perceived as linguistic imperialism (Tsui, p. 2, cited from Phillipson).

This will lead to the discussion of to what extent how far EMI and learning English could contribute to the understanding of the subject matters.

Are using EMI in teaching and learning English inter-related? While some educators address that EMI would make students feel perplexed in terms of understanding, Angel Lin argues that the development of a strong English enrichment programme that has a focus on academic registers of the subjects could facilitate students understanding of the subjects in English better (Lin, p. 83). The boundary between teaching subjects in English and using English has to be 'cross-overed' or 'destabilised' by this innovative approach (ibid). For example, learning Science in English is mastering the discourse of Science in a discipline-specific way in English (ibid, p. 85). The awareness of and collaboration between English teachers and content subjects should be promoted in immersive learning English environment that an EMI school is obliged to

In view of the fact that the general English standard of students in CMI schools will decline, more English enhancement courses could be provided for CMI students that would enhance their exposure to English. For example, English Enhancement Scheme was introduced in CMI schools to strengthen the teaching and learning of English holistically in a strategic way to ensure the English proficiency of CMI students could be improved

(http://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/edu-system/primary-secondary/applicable-to-secondary/moi/support-and-resources/english-enhancement-scheme/edbcm06047e.pdf ). Although there lies in the assumption that the English standard of EMI students is higher because of more exposure, compared with CMI students, many parents overlook that the intension of government implementing mother tongue in class is to facilitate students understanding in class. Rather, parents believe that if their children can get into the scarce elite EMI schools, more opportunities at work or in further studies of their children in the future can be guaranteed. Sadly, this is against the government's language policy of carrying out the intended outcomes.

The controversial issues over implementing mother tongue policy in school have opened up an alternative, which is to employ code switching and bilingualism in class.

Code-switching and bilingualism

It is argued that code switching and bilingualism not only consumes a lot of time in teaching, but also it is 'detrimental (for students) to learn Chinese or English well (Lu, p. 376)’. However, some teachers may claim that code switching and bilingualism could improve students understanding in class, or even increase their vocabulary in two languages. As David Li stresses, 'outlawing code switching (and bilingualism) as a cause of lower achievement in language learning has mistaken the symptom of the disease (Lu, p. 378, cited from Li).'

In fact, the new language policy of implementing mother tongue policy in class would affect students adapting to English medium education that could be bridged to university education. After finishing their secondary three, there is no guarantee they will be able to use EMI which is necessary in university studies. As Dan Lu puts it, it will 'impede the students' growth in their academic studies with this switch from one medium to another (ibid., p. 378).' This is a flaw of adopting CMI in school.

Methodology

The language policy issues discussed can be exemplified in my English teaching in a university college. This methodology I use is to testify the language and policy issues in my role of being a teacher as a reflective educational practitioner. The findings in discussion will shed light on the practice of language policy in actual language classroom, thereby opening up new insights into language teaching pedagogy.

Findings in discussion

1 Global English in relation to Hong Kong

English is an international language with which to increase human capital. The higher proficiency one speaks in English, the more opportunities in jobs and studies one can get. English as an international language has its recognition worldwide. English becomes global. As an English teacher, I have the vision of inculcating students with more opportunities to speak English. My philosophy is that students should not only speak English in class but also speak English outside class. As youngsters are pillars of society, if they are well trained to speak English, they could contribute to society more effectively and efficiently in English. The unprecedented rise in global English propels them to necessitate the use of English in society.

While the spread of global English exists, the Hong Kong government intervenes by highlighting it is a national mission to carry out language policy to promote the use of English. I, as the English teacher, correspond to the government's language policy in practice. Language policy is all about language practices, language ideology or beliefs and language management or planning (Spolsky, p. 186). My national mission in teaching English is to integrate materials about Hong Kong history so that students can construct their Hong Kong identities. Hong Kong was a fishing village in the past. It was then turned into entrepôt, where business and trade took place. It was later developed into manufacturing industry, for example, garments industry. Students were so excited to know about the past of Hong Kong. The handover of Hong Kong in 1997, a historical moment of Hong Kong, was most striking to the students. They were skeptical about whether they were Hong Kongers or Chinese "under one country, to system". Through these Hong Kong teaching materials, students were gaining more awareness of Hong Kong history and thus their national identities had been constructed. Learning English is not simply about learning a language itself. In the Hong Kong classroom context, it could encompass knowing about Hong Kong history, culture, memories and national values. As Amy Tsui points out, ‘Embodied in a language is the history, the beliefs, the cultures and the value of the speakers (Tusi, p. 2).’ I as the English teacher believe that the national mission of teaching English in correspondence to language policy has been successful.

2 Appreciating the interrelations between Language and Culture

Preserving national cultural identities and promoting foreign language are crucial to the government putting forward the language policy.

A Preserving national cultural identities

As I mentioned previously, integrating materials on Hong Kong history into English lesson could enable students to construct and reconstruct their Hong Kong identities in critical reflection.

Also, learning authentic "dim sum" vocabulary in English allows students to communicate with foreigners their Chinese culture. This could reinforce their sense of belongings to the Chinese culture.

B Promoting foreign language

Exploring British culture through visits, media and other different forms in class and outside class could help students to learn English better. Immersing in British culture would eventually get them familiar with English language and culture. For example, newspaper about royal British family not only stimulates their interests in the establishment of royal British history but also arouses them to learn royal British languished in distinction with lower class or grassroots.

Besides, learning authentic British "full breakfast" and other British food vocabulary could tap students into British food culture. Examples are muffins, scones, sausage and scrambled eggs.

C Cross cultural experience and Intercultural Communication

Students could resort to speaking English to talk about their Chinese and British cultures. With high proficiency in the global language English, they are competent enough to speak of cross cultural experience dexterously.

It is indeed one of the educational aims that students are trained to develop excellent intercultural communication skills. For instance, students could take advantage of English to communicate with foreigners about their Chinese culture; likewise, they could be able to comprehend what the British is talking about the British culture.

Language and culture are inseparable. To speak a language well, one must be immersed in the culture to heighten their sensitivity to using the language. In teaching students in my English class, I was attempting to put the government's language policy into practice. That is, to preserve national cultural traditions while to promote a foreign language, in the appreciation of the interrelations between language and culture.

I am a non-native speaker (NNS) who teach English

In the English team, there were native speaking (NS) colleagues and non-native speaking (NNS) colleagues. I was a non-native speaker (NNS) who taught English. Even though students might feel that non-native speaking (NSS) teachers are less superior and competent than native speaking (NS) teachers, I tried my best to convince them that my experience as a second language learner of English could be valuable for them to learn English reflectively. For instance, I listed out many common errors of second language learners so that their sense of awareness of not committing to making those mistakes could be heightened. An example is that many Hong Kong students wrote 'There have trees.' The error of 'there have' is so common in their system of Chinese language. In English, 'there are trees' is correct because of the existential meanings of verb to be. There 'is/are' is right, but not there 'has/have'. The listing of common errors for second language learner is so helpful as they may not be able to detect them as a second language learner. I can fulfil mission of being an English teacher who can use the edge of sharing experience in learning English as the second language to benefit Hong Kong students to learn English.

EMI vs. CMI, bilingualism and code switching

My college policy stipulates that the subject English must be conducted in English as the medium of instruction.

This could be detrimental to those who are weak in English or those mature students who find it hard to catch up with English.

In order to facilitate the majority of students learning English in class, in the first lesson, students were asked to allocate time to learn different aspects of English- reading, writing, speaking and listening regularly and equally to obtain autonomy in learning. Independence learning was strongly encouraged so that they could practice English not only inside class but also outside class. Also, resources were provided, such as BBC links for listening practice. As a teacher, I believe I have the mission of training students to be independent, autonomous and industrious English learners.

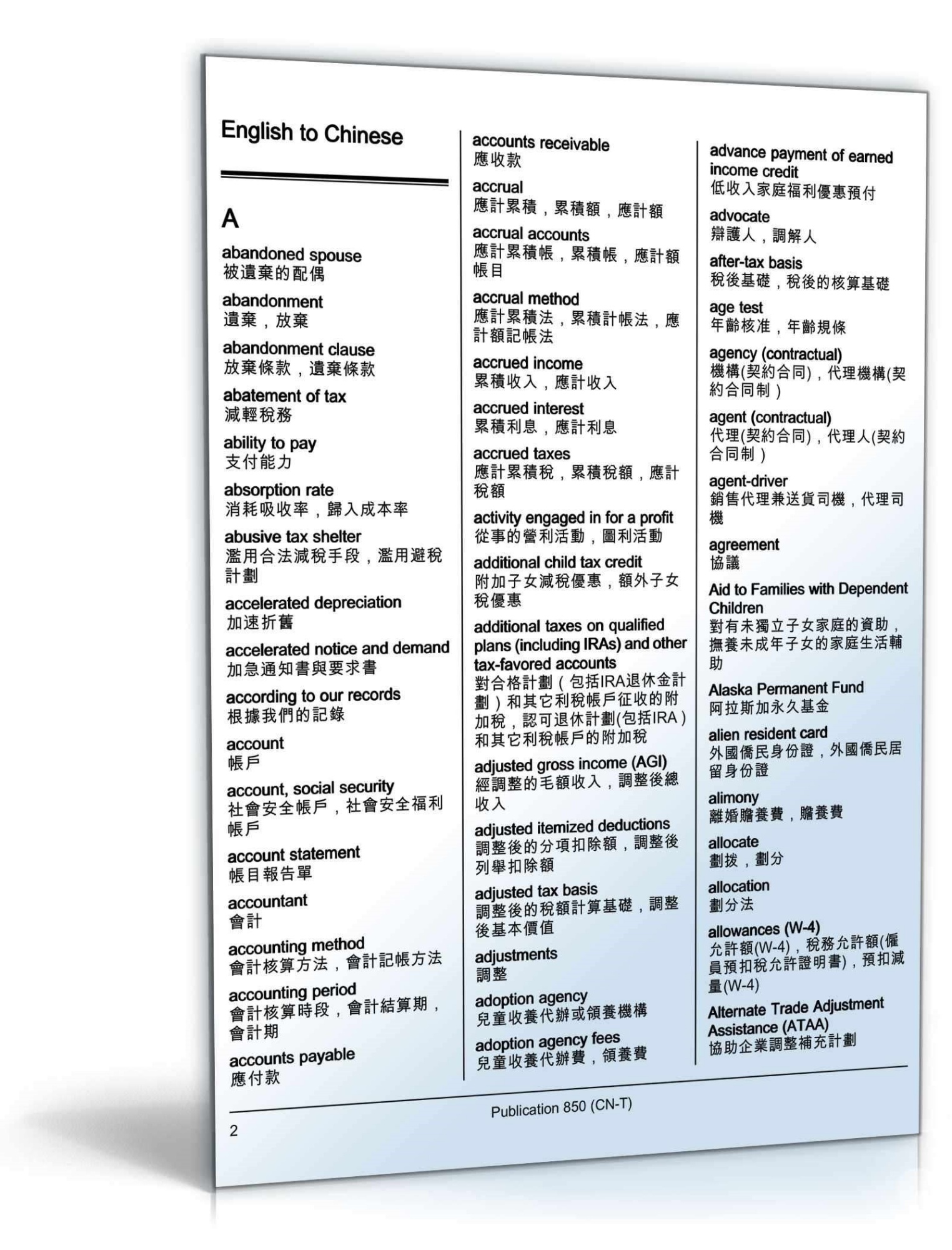

Provided that students did not have a habit consistently to learn English by their own initiatives, it could be difficult if students could hardly understand English in class. The use of Chinese was forbidden. What the teacher could do is to provide some prompts in some simple and clear of instructions, for instance, guessing what the word means by the context itself or looking at the speaker's gesture. Natural acquisition of language is all by guessing and remembering. If code switching for some of the vocabulary was not allowed in speaking, perhaps students could be asked to jot down those words that were put down on the board, and at home they could write down words in translation in the form of (English-Chinese) glossary on the notebook and study them hard. These are the methods I could devise to help students to learn better in English.

Conclusion: New Insights into Language Teaching Pedagogy

To sum up, English has a global status. To arouse Hong Kong students in learning English, Hong Kong history and Hong Kong “dim sum” can be integrated into English class so that they can be more resonant with Hong Kong by building up their Hong Kong identities. This is in line with the Hong Kong government policy upholding the preservation of maintaining national traditions while promoting foreign language. Cross cultural experience and intercultural communication could be fostered. To see how all these intertwine, I as a non-native speaker (NNS) share my English language teaching experience so as to put my language practice and language beliefs or ideologies into language management. These triangular results open up a new insight into language teaching pedagogy, which is to immerse oneself in the culture to have 'a vision' of the ways in which "the language is being used in the culture".

New Insights in language teaching pedagogy

It is crucial to

IMMERSE oneself in the culture

to have a VISION of the ways in which

“the LANGUAGE

is being USED in

the CULTURE”.

References

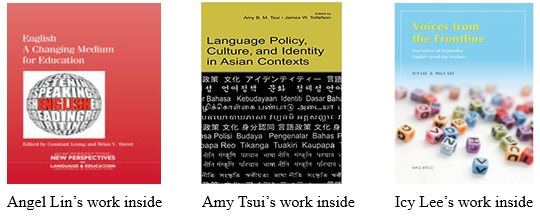

Lin, Angel. “Multilingual and Multimodal Resources in Genre-based Pedagogical Approaches to L2 English Content Classroom” in English: a Changing Medium for Education, edited by Constant Leung and Brian V Street, Bristol: Multi-lingual Matters, 2012.

Lu, Dan. “English in Hong Kong: Super Highway or Road to Nowhere? Reflections on Policy Changes in Language Education of Hong Kong” in Regional Language Centre Journal, 34.3 (2003), p. 370-384

Tsui, Amy B. M. “Language Policy and the Social Construction of Identity: the case of Hong Kong” and “Language Policy and the Construction of National Cultural Identity” in Language Policy, Culture and Identity in Asian Contexts, ed. By Tsui, Amy B. M. & Tollefsen, James W., London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007.

Janks, H. “The Access Paradox” in English in Australia. 139 (2004): 33-42

Lee, Icy & Sze, Paul. Voices from the Frontline: Narratives of Nonnative English Speaking Teachers. Hong Kong: the Chinese University Press, 2015.

Spolsky, Bernard. Language policy. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

HK EDB links:

Note. Esteemed scholars on language policy in Hong Kong: Angel Lin, Amy Tsui and Icy Lee

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Course for Teachers and School Staff at Pilgrims website.

The Good Teacher, the Metaphorical Tickle Trunk, and the Survival of the Fitter

Terence McLean, CanadaWhy I Am and Am Not Just a Teacher: A Reflection on Teacher Identity and Classroom Emotion in Language Learning

Richard Pinner, JapanCatalysts for Narrative Reflection from Other Fields

James W. Porcaro, JapanThe Power of a Successful Classroom… Principles to Live By

Lisa Ng, MalaysiaLanguage Policy: The Case of Hong Kong

Ivy Lai Chun Chun, Hong Kong