- Home

- Various Articles - Reading

- Small Versus Whole Group Reading Instruction in an Elementary Reading Classroom

Small Versus Whole Group Reading Instruction in an Elementary Reading Classroom

Kelsey Martinez, Med, has been an elementary teacher for three years and recently completed her master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Cincinnati, OH. Email: marti3kz@mail.uc.edu

Linda Plevyak, PhD is the graduate director of the School of Education at the University of Cincinnati, OH. Email: linda.plevyak@uc.edu

Abstract

An effective teacher is one who is always striving to best meet the needs of the students they serve. To do this, the type and quality of instruction being provided must constantly be evaluated to assure effectiveness. Techniques and strategies that may have once been considered most effective might no longer meet the needs of the current population of school-age children. In this study, strategies for best practice for reading comprehension instruction to occur in mixed-ability 2nd grade classrooms are explored with a goal of determining the most effective way to assure mastery of Common Core State Standards for Reading. Small group, differentiated reading instruction is compared with whole group, generalized instruction in order to determine how the needs of students can best be met in elementary classrooms. The findings of this study support the idea that students learn best in a differentiated, small group setting where the teacher meets student needs within their Zone of Proximal Development using texts at individual, instructional reading levels.

Introduction

Teaching and learning styles have evolved drastically throughout the history of public education. These changes happen as a result of shifts in society, the value and emphasis placed on education, changes in students themselves, and, most importantly, changes in our understanding of how educators can best meet the needs of our students. These changes serve to help us achieve the goal of elementary education, which is to build and support a strong foundation for learning, especially in reading. While there is no single right or wrong way to best educate today’s youth, an argument can be made that students are not all the same, and, therefore, do not learn in the same ways. While students often share common academic goals, the learning paths they require to reach said goals vary greatly from one another (Roy, Guay, & Valois, 2014). It is becoming increasingly clear that when students are viewed as one collective, unified group, many learners fall through the cracks of our educational system on both the high-achieving and low-achieving ends of the learning spectrum.

Traditional classrooms are learning environments that utilize instructional techniques aimed to provide all students with the same instruction in the same way at the same time (Tieso, 2003). These classrooms are teacher-focused, textbook driven, and rely heavily on lecture. Because of this, teachers often employ teaching strategies that ‘teach to the middle’ with the goal of reaching a majority of the students through generalized instruction (Nicolae, 2014). While many students can adapt to this teaching style and are able to find success, a large population of students, on both the lower end of the learning spectrum and students who struggle to stay focused in whole-group settings, struggle to grasp concepts and keep up with the rest of the class. While it may not seem like a significant problem for a handful of students to not comprehend one unit of information, when this problem is viewed from an elementary perspective—where students are learning how to read—we can easily see how the inability to master basic skills can negatively impact future learning and success across multiple content and social contexts.

Much research has been done to support the idea that a change needs to be made to our current teaching practices to better support and meet the needs of our elementary students, and many agree that differentiation will play an important role in this change. While differentiation can take many forms, one of the most effective styles for early elementary students in heterogeneous classrooms is small group instruction. A small-group, differentiated learning environment is one where instruction is administered in small group settings and targeted to meet individual student strengths and needs. This small group instruction is a pedagogical practice designed to accommodate the differences between students and tailor instruction to their readiness levels and learning styles to promote maximum personal growth (Valiandes, 2015).

Differentiation is a unique teaching style because it recognizes students’ strengths and provides resources to strengthen their weaknesses (Suprayogi, Valcke, & Godwin, 2017). While many believe that differentiation is important, a disconnect can still be seen between this understanding and actual implementation in the classroom. It is fairly easy for a trained teacher to see differences in students’ reading abilities and where their strengths and weaknesses lie, though many teachers struggle to find an effective way to begin and maintain small group instruction that can target and assess students’ needs in an organized way or for them to master the Common Core State Standards. Hence, this study focuses on the following question, when compared with generalized, whole group instruction, how does small-group reading instruction impact second grade students in meeting required state standards in a mixed-ability classroom?

An action research project to compare small-group reading instructional strategies and generalized, whole group instruction will be conducted to determine the most effective way to assure students are learning and mastering all reading State Standards while receiving instruction at their individual reading levels. The outcome of this project will provide information about whether instruction is more effective when all students are working in leveled small groups on the same skills, with differentiated reading materials, or if all students should work from the same mentor text with instruction occurring in a whole group setting. This project is important because while all students are unique and enter the classroom with various levels of reading abilities, they are all held to the same standards and are assessed over their mastery of those standards at the end of the school year. It is important to determine the most effective use of instructional time in order to assure that students are getting the most out of their instruction, and that instruction targets the various needs observed at different reading levels.

Review of literature

This literature review is organized into three subsections. Together, these subsections will provide evidence to outline the need for differentiated instruction to support early reading growth in elementary students and the ways it can be most effectively implemented in the school setting.

Quantity versus quality of instruction

We often hear the phrase ‘practice makes perfect’ in terms of helping students meet and master reading goals. Topping, Samuels, and Paul (2007) define practice as, “facilitating the transfer from working memory to long term memory, so consciously controlled processing becomes automatic processing (associated with higher speed and lower effort)” (p. 254). This implies that the more a student is exposed to an idea, concept, or text, the greater the chances it will be absorbed and internalized. The problem with this way of thinking arises when considering the types of questions students are being asked that allow them to work toward a high quantity of practice. Another problem occurs when considering the pace students work and process. In the time it takes one student to answer one question, another could have completed five, which brings into question the quality of instruction slower working students are receiving if they do not have access to as wide a variety of questions or adequate processing time. Research shows that quality reading instruction targeted to individualized student needs is more beneficial to student achievement than the quantity of instruction.

Much of teaching and student learning happens as a result of teachers asking questions in order to elicit student responses that demonstrate their understanding of concepts being taught. If a student can accurately answer a question, it can be assumed that they have a solid foundation of understanding that topic. The types of questions that teachers ask can be categorized into levels of knowledge measured in Bloom’s Taxonomy—ranging from higher order questions, requiring reflection and thinking beyond the text, to lower-order questions, requiring recall of facts (Şahin, 2015). Şahin (2015) studied the types, quantity, and quality of questions asked in the classroom in order to determine their effect on student understanding and reading comprehension. The results of this research show that asking fewer, higher-order, guiding questions provide students with a deeper grasp of concepts than more, lower-level questions. While practice is important in order to help students become better readers, the quality of that practice plays a larger role in their academic success than the sheer mass of questions to which they are exposed.

This understanding leads to the need for teachers to create an environment that promotes both quality reading and reading instruction for all students. While it is beneficial to know that quality should be strived for, the question now becomes how can this quality-reading environment be established in elementary classrooms containing a wide variety of reading abilities? Topping, Samuels, and Paul (2007) investigated this question, finding that both quality reading and quality reading instruction allows for maximum student growth across grade levels. Opportunities for quality reading come from providing students with reading materials within their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which is where they are pushed just slightly beyond their comfort zones in order to challenge themselves to become better readers. Quality reading instruction comes from meeting students at their individual levels to ask higher-order thinking questions and promote stronger comprehension. These higher-order thinking questions will vary greatly with the wide range of reading levels that can be found in a typical, early-elementary classroom. This requires an environment that allows for all students to receive guided, quality reading instruction at their level. Topping, Samuels, and Paul (2007) state, “Appropriate, effective implementation involves not only the monitoring of reading practice, but also implies action to guide the student toward successful comprehension” (p. 262). This individualized guide toward success is the foundation of a differentiated learning environment.

With quality instruction occurring in small, focused, guided groups, an obstacle many teachers face is assuring that student learning is equitable and allows for every individual to show growth. When reading levels vary as greatly as they do in elementary classrooms, it can be easy to assume that differentiated instruction is not equal if students are working at different levels and on different concepts or strategies. Valiandes (2015) aimed to investigate the equity of differentiated instruction, finding that while students may be working at different levels and on different tasks, focused work in their ZPD served to provide higher-quality learning—as measured by their end-of-year growth—than traditional, teaching-to-the-middle practices (Valiandes, 2015). Through the use of differentiated instruction, teachers are able to target instruction to students’ strengths and scaffold learning in areas where they show weakness, which is not something that can be as easily accomplished in a whole-group setting. Instruction that teaches to the middle, which often occurs in whole-group instruction, can result in students not achieving to their full potential (Connor, Morrison, and Underwood, 2007).

When approaching the idea of equality from a differentiation mindset, it is important to understand that equity does not mean ‘equal’ or ‘same’, because each student is not the same. Rather, equity comes into play through the high expectations and opportunity for challenge that differentiated instruction affords each student by meeting them where they are within their ZPD (Valiandes, 2015). Quality instruction is that which helps a student make growth toward their own individualized goals, with differentiation serving as a tool to help close the achievement gap that often is unsupported through generalized, traditional teaching practices.

Reading behaviors and reading environments

Differentiated instruction is an effective instructional strategy that allows for teachers to teach students to read using strategies that best fit their learning styles. Not all students learn and achieve in the same ways, therefore, reading instruction must be tailored to individual students needs in order to allow for maximum student growth (Connor, Morrison, and Underwood, 2007). Students in early elementary grades come to the classroom with very different levels of exposure to written and spoken language, significantly affecting their vocabulary development and their comprehension skills as they begin learning how to read. With this high variation between student reading abilities, struggling students may develop a negative self-concept and attitude toward reading when they compare themselves to their peers during generalized, whole-group instruction. Roy, Guay, and Valois (2015) investigated the effects of differentiated instruction strategies on academic self-concept, finding that when classroom environment is adapted to meet the needs of individual students, feelings of negative self-concept related to reading ability were reduced. When instruction is differentiated and students are able to work toward personal goals by demonstrating understanding in a way that reflects their learning styles, struggling readers at this age are less likely to compare themselves to their peers, but rather can use their own growth and achievement to form the basis of their self-concept (Roy, Guay, & Valois, 2015).

By establishing a positive attitude toward reading early in reading development, especially with struggling readers, teachers can help foster a positive outlook toward reading that will follow students through their academic careers. LaRocque (2008) investigated the relationship between students’ feelings toward their classroom environment and their academic achievement. LaRocque (2008), found that students need to feel safe, challenged, and satisfied with their learning environment in order for instruction to be effective. Through a differentiated learning environment, students can feel safe knowing they are being challenged at their developmental level, with a goal of showing personal growth. This allows for teachers to create a safe learning environment that encourages students to push their reading abilities and make mistakes without fear of failure or of being compared to peers.

When creating this safe, but challenging differentiated learning environment that fosters reading growth, it is important to consider the type of instruction and the expectations of reading that are being set both explicitly and implicitly throughout the day. McIntyre (1992), in her study of how classroom contexts establish beginning reading behaviors, found that the expectations teachers set for reading in different contexts of the school day play a large role in the behaviors observed in beginning readers. When students are learning to read, independent, unstructured reading time, such as silent reading, is often ineffective in helping students build fluency and comprehension because they do not yet know the expectations of reading and how to gain meaning from a text. Early elementary students just learning to read do not yet have the stamina or independence to develop reading skills and require a close teacher presence to help them begin to read for meaning. McIntyre (1992), states, “an ideal setting could include social interaction in small groups where the expectation is clear that children will successfully read” (p. 368). Through these small groups, the teacher can establish an expectation of reading for meaning by differentiating instruction to target specific strengths and needs of students within their individual reading levels.

Connor, Morrison, and Petrella (2004) in their study of beginning-of-the-year reading comprehension skills and effective types of instructional activities, found that student reading levels at the beginning of the school year play a very important role in the type of instruction that will allow them to show the most growth in their reading comprehension throughout the school year. Students who enter the school year reading above grade level benefit more from child-managed explicit instruction while students reading at or below grade level require teacher-managed explicit instruction in order to meet grade level reading and comprehension expectations (Connor, Morrison, & Petrella, 2004). This means that students reading above grade level can be successful with tasks where they are asked to complete a specific task more independently while on grade level and struggling readers require more structured, teacher lead instruction to complete reading tasks. This is important to consider when planning and implementing instruction in the classroom because not all strategies work for all students. When instruction is targeted specifically to the needs of the individual student, greater learning and growth is able to occur. This will not only allow struggling, lower achieving students to make appropriate growth based on their individual needs, but it will also provide opportunities for enrichment for higher achieving, advanced students, whose needs are often not effectively met in traditional classroom settings (Tieso, 2003).

Teachers’ beliefs towards differentiation

While a differentiated, small-group learning environment has been shown to provide the supports and setting necessary to meet the variety of needs seen in beginning readers, this teaching style is still not effectively used as common practice among a majority of early elementary reading teachers. In classrooms where teachers are attempting to create a differentiated classroom, they often do so in a way that doesn’t center on the individual needs of the students. In these cases, teaching remains the same for every student, but is administered in small groups rather than a whole group. This disconnect between theory and practice begs the question: Why aren’t teachers implementing the strategies they know to be beneficial for young readers?

In order for differentiation to successfully occur in classrooms, teachers need support, tools, and resources to help develop confidence in their abilities to effectively implement best teaching practices. One of the main reasons teachers find it difficult to utilize small groups in the classroom is because they lack confidence in their abilities to successfully implement this teaching strategy. Suprayogi, Valcke, and Godwin (2017) found that teachers who had high self-efficacy were more likely to attempt and keep up differentiation practices in the classroom than teachers with low self-efficacy.

Differentiation can be an extremely daunting task because it requires teachers to both proactively modify existing curriculum to fit the small-group setting and constantly adjust materials, teaching strategies, and groups as students’ strengths and needs change throughout the school year. Adapting teaching practices in this way requires a shift in thinking about what teaching looks like in the everyday classroom. Small-group instruction requires teachers to move away from a teacher-focused mindset to a student-centered approach with consideration of individual student strengths and needs at the forefront of decision-making (Nicolae, 2014). Many teachers don’t feel willing or able to put in the time and effort needed to commit to the task of differentiating their instruction, and therefore, choose to stick with traditional, generalized teaching practices for matters of convenience.

This lack of confidence many teachers feel relating to their ability to successfully create and manage a differentiated learning environment stems greatly from the absence of opportunities for teachers to see effective differentiation in action. Suprayogi, Valcke, and Godwin (2017) state, “without a solid understanding of a theoretical rationale, teachers find it difficult to implement new ideas in the classroom” (p. 294). When teachers have opportunities to see and experience small-group differentiation in action, through professional development opportunities or observations of colleagues’ teaching, self-efficacy improves because teachers feel supported in their efforts to try something new. In their study of the factors that lead to successful implementation of differentiation practices in schools, Smit and Humpert (2012) found that schools with teachers who were like-minded, supportive, and open to trying new things were more likely to implement differentiation practices with success, as measured by student growth on end-of-year standardized assessments. Walker-Dalhouse, Risko, Esworthy, Grasley, Kaisler, McIlvain, and Stephan (2009) find that differentiation works best when teachers work together to provide supports the students need. This happens best when teachers are provided with opportunities for professional development and given opportunities for observation of and continued support by fellow teachers experiencing success. These studies show us that an academic community, where teachers feel supported by their team of fellow teachers, is necessary for differentiation to take hold. These communities of like-minded teachers promote an easier transition into the implementation of this challenging, new teaching practice.

Discussion

Within this literature review, a need for small-group, differentiated instruction was established by highlighting the ways in which students benefit from this teaching practice in ways that traditional, generalized teaching strategies do not. All of the research analyzed through this literature review showed that differentiation strategies are not a quick, easy fix to meeting the needs of the wide range of readers seen in early elementary classrooms, but it is a necessary step to assure that all students develop a strong foundation for reading.

An open, supportive community of teachers and school leaders with a shared commitment to doing what is best for each and every student is essential for differentiation to take root and allow results to be observed through an increase in reading abilities. The creation of an environment where teachers feel safe and supported in their attempts to try new techniques and feel comfortable in sharing their success with colleagues is a direct reflection of the administration of a school. Findings from the studies included in this review support the idea that when principals and other school leaders work diligently to create an environment where teachers feel supported, empowered, and encouraged by their community, differentiation is more likely to be seen implemented successfully in classrooms (Goddard, Neumerski, Goddard, Salloum, & Berebitsky, 2010).

Methods

Participants

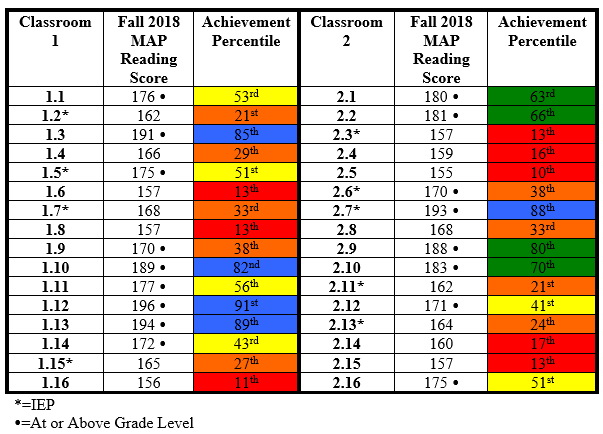

Research for this study was completed in a rural, Southern Ohio (United States) school in a district of around 1,500 total students. The study was conducted in two separate 2nd grade classrooms, each composed of readers with abilities ranging from beginning of first grade level to middle of third grade level as measured by the Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System. Classroom 1 is the classroom that received individualized, small group instruction while Classroom 2 served as the control classroom and received standard, whole group instruction for the purposes of this project. Both classrooms worked on the same standard over the course of this study. Classroom 1 had a total of 22 students. Five of those students were on Individualized Educational Programs (IEPs), one of which had reading goals that were serviced by our Intervention Specialist rather than small group, classroom instruction, and therefore were not included in this study. Classroom 1 also had five students who received TITLE 1 reading services by a specialized reading teacher, and therefore were not included in this study. This brought the total number of participants in this study for Classroom 1 to 16 students. Classroom 2 had a total of 23 students. Five of those students were on IEPs, but still received whole group instruction and participated in this study. Six students in Classroom 2 received TITLE 1 reading services and were not included in this study. This brought the total number of participants in this study for Classroom 2 to 16 students. Participants in this study that were on an IEP are noted in all tables with an asterisk (*).

Procedure

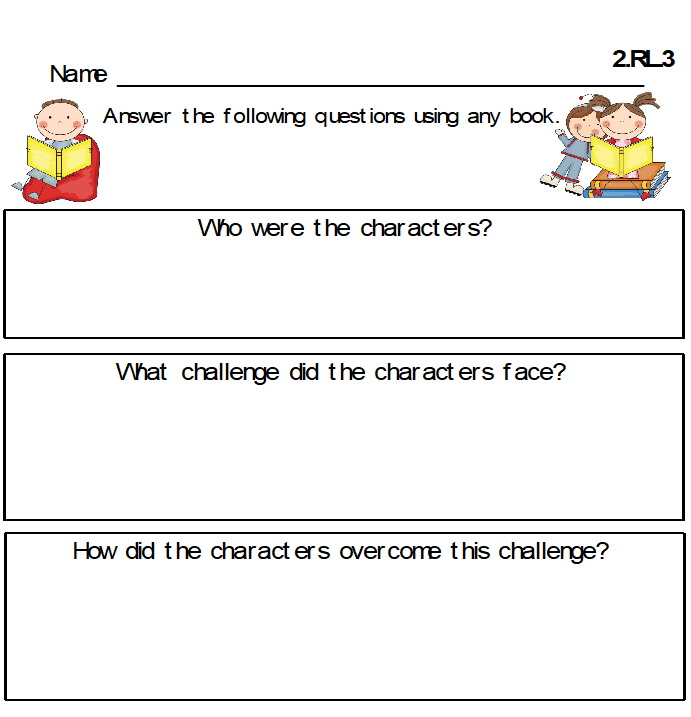

Through this study, data have been collected and analyzed to answer the following question: when compared with generalized, whole-group instruction, how does small-group reading instruction impact second grade students in meeting required state standards in a mixed-ability classroom? To answer this question, I have explored various ways reading instruction can be administered with an overall goal of assuring all students at all reading levels master the goals outlined in Ohio’s Second Grade Common Core State Standards (CCSS). Participants in this study are mastering Ohio’s Second Grade CCSS 2.RL.3: Describe how characters in a story respond to major events and challenges. This is a reading comprehension skill that students in second grade are expected to master in order to develop their reading abilities and deepen their understanding of the texts they read. In this study, students answered questions about who the characters in a story are, what challenges they face, and how they overcome their challenges. A copy of the graphic organizer used to analyze all texts in this study can be found in Appendix A.

In this study, two classrooms of students are used to evaluate the effectiveness of various teaching styles with the outcome being student mastery of CCSS 2.RL.3. A description of the participants was given in the ‘Participants’ section of this study. The first teaching strategy used is small-group, differentiated instruction, organized by providing standards-based instruction through the use of leveled texts at each groups’ individual reading levels. In this model of small-group differentiation, all students will be working on the same skills at the same time, but they will be doing so using a text that is at their instructional reading level. The second teaching strategy is whole group instruction that provides standards-based instruction through the use of a common, mentor text. In this traditional model of reading instruction, all students will be working with the same text and they will receive whole group, generalized reading instruction to complete these tasks based on the needs of the average student observed in the classroom.

This study took place over the course of two weeks. While this is not an adequate amount of time to truly evaluate the effectiveness of various teaching strategies, it did allow students to become familiar with the standard and the texts used to monitor student growth and achievement. Both classrooms began this study by taking the same Pre-Assessment, which asked students to read No Bullying, a 160-word, grade-level passage and respond to the questions from Appendix A. Students in both classrooms were asked to complete this cold-read task independently, which means this was the first opportunity students had to view and respond to the text. This pre-assessment, and all other activities in this study, were graded using the common rubric located in Appendix B.

Students from Classroom 1 were divided into small groups based on their Fountas & Pinnell (F&P) reading level measured at the start of the school year. These reading groups met with the teacher every day for 15-minutes over the course of the 2-week study. Each week, students read a text at their reading level and worked together to answer the questions from the graphic organizer in Appendix A.

In week one, students reading at a level I read the story The Last Muffin by Jenny Feely, a F&P level I text, students reading at a level J read the story The Ugly Duckling by Maryann Dobreck, a F&P level J text, and students reading at a level L read the story Moving by Mia Coulton, a F&P level L text. The first three days of small group instruction were spent taking turns reading the stories aloud two times in order to build fluency and increase comprehension of the texts. Students were also asked to read the story to themselves during their Read-to-Self time when they were not working with the teacher in small group. The last two days of small group instruction were spent discussing and answering questions from the graphic organizer located in Appendix A. Our focus was on answering questions in complete sentences and restating the question within our answers.

Classroom 2 completed the graphic organizer located in Appendix A together as a whole-group using the story The Rough-Face Girl by Rafe Martin, which is a text used in our second grade Fairy Tale Unit reading curriculum. This text was read aloud to both classes and students completed the standard lessons and activities associated with this text as outlined in our reading curriculum guides. In addition to this, Classroom 2 also participated in whole group-teacher lead discussions centered around answering questions about characters from the story and the challenges they faced. At the end of the first week of instruction, both classes were asked to complete the 2.RL.3 graphic organizer to serve as a formative assessment midway through the study to measure the effectiveness of both teaching strategies thus far.

For week two of this study, students from Classroom 1 were again divided up into their leveled reading groups. These groups remained the same as week one. This week, students in the level I group read the story The Spelling Bee by Jill Sherman, level J read the story Monster Cowboy by Maribeth Boelts, and Level L read I’m The Guest by Karen Mockler. Reading groups again spent the first three days taking turns reading the stories two times each, as well as once independently during Read to Self. The last two days of small group instruction were spent answering questions from the 2.RL.3 Graphic Organizer (Appendix A). This week, the focus of instruction was on providing evidence to support our answers when identifying the challenges from the story and how the character overcame this challenge. Classroom 2 continued to verbally engage in whole-group, teacher lead discussions about the characters and challenges of a story using the next mentor text from our Fairy Tale unit, Cendrillon by Robert D. San Souci. This text was read aloud to the class by the teacher and the teacher modeled answering the 2.RL.3 Graphic Organizer questions for the whole group.

Both classrooms also ended this study by taking the same Post-Assessment, which asked students to read a 379-word, grade-level story, I Broke it by Edie Evans, and respond to the questions from Appendix A. This is a level J text as measured using the F&P leveling system. According to this leveling system, students should be reading at a level J at the beginning of second grade. In both classes, students with a reading level of J or higher—as measured by the benchmark assessment scores second grade teachers collected at the start of the school year—read this text to themselves and completed this assessment independently while students reading at a level I or below read this text aloud in a small group with the teacher. This post-assessment was also graded using the common rubric from Appendix B.

Results

Across both classrooms, students in this study started this school year struggling with their reading and reading comprehension. The results from the Fall Reading MAP test students took at the start of the school year showed that only 56% of students in Classroom 1 and 50% of students from Classroom 2 were reading at or above grade level (Appendix C). While this is not the only tool used to measure student achievement, MAP Scores do play a very large role in both students’ projected success on the 3rd Grade Reading Guarantee State Assessment they will take next year, and teacher yearly evaluations of effectiveness. Based upon the overall scores observed in these classes, it is clear that implementation of a rigorous instructional practice is essential to help these struggling readers become successful and return to an ‘on-track’ status for future reading assessments.

Pre-Assessment

The results of the Pre-Assessment students took at the start of this study showed that overall, the two classrooms that participated in this study were very comparable in ability. The average score on the No Bullying Pre-Assessment for Classroom 1 was 10.4/16 and the average score for Classroom 2 was 10.4/16. This shows that both classrooms started out with a comparable level of background knowledge regarding their understanding of the 2.RL.3 standard measured in this study. Some of the biggest gaps in understanding observed in both classes as measured by student performance on this Pre-Assessment were in students’ abilities to answer questions in complete sentences and provide evidence to support their answers. When answering the questions about the challenge characters faced and how they overcame this challenge, a common student answer was “A mean girl” or, more simply, “Ivy”. While this is not technically an incorrect answer—as Ivy was the bully in this story—answers like these lack a depth of understanding by the student necessary for student success with this skill as they continue to work with more challenging and complex texts. The results of this Pre-Assessment were the driving factor for the focus of instruction over the course of this two-week study.

Week 1 instruction

Following the Pre-Assessment, Classroom 1 began small group instruction with texts at each group’s instructional reading level. All students in Classroom 1 showed growth on this activity as compared to the Pre-Assessment, with the biggest growth in scores coming from students’ use of complete sentences and their ability to restate the question within their answers. While this growth is exciting to see, it is important to note that the graphic organizer from Appendix A was completed together in each group, with heavy modeling and a discussion of responses prior to students writing their own. Guided Reading Group Week 1 scores are not a true measure of student mastery of this standard, but rather served as a practice tool for instruction occurring throughout the week with specific skills within this standard.

A more true sense of the effectiveness of instruction that occurred in Week 1 can be seen in the results of the Formative Assessment given at the end of Week 1. While all scores from Classroom 1 went down from their Guided Reading Group Week 1 scores, almost all students showed improvement on this assessment as compared to the Pre-Assessment scores. Only students 1.3 and 1.8 received the same score on both the Pre and Formative Assessments. This shows that while students were not able to apply all new learning and understanding gained from Week 1 Guided Reading Group instruction to their own, independent work, the instruction that took place throughout this week did provide students with a better understanding of how to answer questions in complete sentences and how to accurately identify the problem and solution in the story.

Classroom 2 took the same Formative Assessment as Classroom 1. During Week 1 of this study, both classes were reading The Rough-Face Girl as a read aloud during our whole-group reading time, and we completed activities aligned with our reading curriculum using this story. In addition to our assigned reading curriculum, Classroom 2 also studied this text with the focus of mastering CCSS 2.RL.3 for the purposes of this study. Instruction for this week in Classroom 2 was similar to Classroom 1 in that the focus was on answering questions in complete sentences and restating the question within their answer, however the difference was that this was completed through whole group, teacher-lead discussion instead of small groups. At the end of the week, students were asked to apply what they had learned from their week-long discussion and analysis of the text on their own using the graphic organizer from Appendix A. The class average on the Formative Assessment for Classroom 1 was 11.8/16 and the class average for Classroom 2 was 11.3/16.

While the scores for Classrooms 1 and 2 remain comparable when looking at the overall class average, we start to see some variation in the achievement of students in the classroom when we look at the growth of students from the Pre-Assessment to the Formative Assessment. In Classroom 1, as mentioned previously, 87.5% of students showed growth from the Pre to the Formative assessment, 12.5% of students remained the same, and no students showed decline in scores. In Classroom 2, only 62.5% of students showed growth from the Pre to the Formative Assessment, 31.3% remained the same, and 6.2% of students declined in scores. This data shows us that more students from Classroom 1 were able to retain and apply their new understanding from Week 1 instruction than the students in Classroom 2.

Week 2 instruction

In Week 2 of this study, Classroom 1 continued small group instruction with texts at each group’s instructional reading level. 87.5% of students in Classroom 1 showed growth on this activity, and 12.5% of students’ scores declined on this activity as compared to the Formative Assessment. The biggest growth in scores in Week 2 came from students’ use of evidence from the text to support their answers. The two students who received scores that dropped from their Formative Assessment scores (students 1.7 and 1.8), left answers blank seemingly due to lack of attention during their small group instruction and running out of time to complete the activity. While this overall growth is exciting to see, like Week 1, it is important to note that the graphic organizer from Appendix A was completed together in each group, with heavy modeling and a discussion of responses prior to students writing on their own. If this study were to continue, instruction would follow the Gradual Release model, where modeling and scaffolding of these strategies would gradually reduce as student understanding and ability increased. Guided Reading Group Week 2 scores are, again, not a true measure of student mastery of this standard, but rather served as a practice tool for instruction occurring throughout the week with specific skills within this standard.

Classroom 2 continued whole group, teacher-lead instruction of CCSS 2.RL.3 through the use of another text from our reading curriculum, Cendrillon by Robert D. San Souci. This text was again read aloud during whole-group reading time and activities were completed that aligned with our reading curriculum for this story. In addition to our assigned reading curriculum, Classroom 2 also studied this text with the focus of mastering CCSS 2.RL.3 for the purposes of this study. Like Classroom 1, the focus of instruction for this week was on supporting answers with evidence from the text. This activity was completed through whole group, teacher-lead discussion and completed with the teacher writing class-generated responses on the board using the overhead projector. Due to the whole group nature of this lesson, individual scores were not recorded for this activity.

Post assessment

At the end of Week 2, both classes were given the same Post-Assessment to measure student growth over the course of this study. The average score on the Post-Assessment for Classroom 1 was 14.3/16. The average score on the Post-Assessment for Classroom 2 was 11.1/16. Overall, both classrooms demonstrated growth from the start of the study to the end. Classroom 1’s class average grew 3.9 points from the Pre to the Post assessment while Classroom 2’s class average grew 0.7 points from the Pre to the Post assessment. In Classroom 1, 93.8% of students showed growth and 6.2% of students declined in the 2 weeks of instruction. In Classroom 2, 75% of students showed growth, 18.8% of students stayed the same, and 6.2% of students declined in the 2 weeks of instruction.

Conclusions

Through analysis of the data collected as part of this study, both instructional practices presented in this study—small group, differentiated instruction, and whole group, teacher-lead instruction—provided students with an overall better understanding on the standard being assessed than they had coming into this study. In both classrooms, students were exposed to a variety of texts that were used to help build their understanding and ability to identify characters, challenges, and solutions in the stories they read. Even some of the lowest and most struggling readers, like some of the students on IEPs or students who scored in the lowest percentile bands on their Fall MAP Reading Test were able to come away from this 2 week study with the ability to analyze a text more deeply than they were before. This shows us that the expectations and level of rigor presented in this study were developmentally appropriate for the students in these classes as it used their strengths and weaknesses, measured by the pre-assessment, to guide instruction.

The goal of this study was to answer the question: when compared with generalized, whole group instruction, how does small-group reading instruction impact second grade students in meeting required state standards in a mixed-ability classroom? I believe that the results of this study indicate that, when compared with whole group instruction, small group instruction, occurring at students’ individualized, instructional reading level, more effectively target and grow the specific areas of need that students exhibit in their efforts to master new reading comprehension skills. This can be seen most clearly when looking at the amount of growth made in Classroom 1 from the results of the Pre-Assessment to the Post-Assessment. At each benchmark assessment in this unit, almost all students continued to make steady growth from where they started, with a total average growth of 3.9 points from beginning to end. This shows that the instruction students received in the small group setting, with texts at their instructional reading level, were specific to the individual needs of the child and could be tailored to specific problems or needs observed by the teacher at each level. When students were broken up into groups based upon similar reading levels, differentiated instruction helped provide students with reading materials within their Zone of Proximal Development and the teacher was able to more actively see the thinking and ability of all students, specifically the quiet students that tend to shy away from participation in the whole group setting.

By placing these students in smaller groups and giving them texts to work with that they could read themselves with limited scaffolding from the teacher, not only did their confidence increase, but the teacher observed large shifts in their willingness to participate and offer their own answers and opinions. This was a particular struggle that the teacher of Classroom 2 faced through whole group instruction in this study. She found that her students who raise their hand to answer almost every question were typically the ones who made the most growth with this standard, however her quiet students who never ask or answer questions seemed to fall through the cracks, and ended up being the students who made little or no growth in this study. There are strategies like Think-Pair-Share, where students are given the chance to discuss with a partner prior to the teacher calling on a student that could be used to reach these quieter students. While this is a beneficial teaching strategy, it has been my observation that many quiet students still rely heavily on their peers to provide answers, and therefore do not always receive the full extent of instruction when it is presented in this whole group setting. I believe that an unwillingness to ask and answer questions in front of a whole class of peers played a large role in the reason why Classroom 2 only showed a total average growth of 0.7 points from the Pre to Post assessment as compared to Classroom 1’s 3.9 point growth.

Generally, instruction that occurred in the small group setting allowed for more focus and engagement from the students with both the texts and the instruction provided. Having frequent, short, and focused time spent on individual skills with several students rather than a whole group, each student is able to benefit more from the time spent working on each skill. In the whole group instruction, the teacher reported that a lack of attention and focus was a frequent part of instructional time by many students. With as many readers that are struggling to meet grade-level expectations as represented within this study, it is not surprising that maintaining the focus of these students is a challenge. Many of these students do not like to read because it is difficult for them. As beginning of the year second graders, they do not yet have the mental stamina or desire to work through a challenge to better themselves as readers. Because of this, the tasks that we ask our students to complete must be more hands on, engaging, and relatable to the student.

Overall, while the data from this study supports the idea that small group, differentiated instruction allowed more students in a mixed-ability classroom to be successful when learning and improving their reading comprehension skills than whole group instruction, it is important to remember that the size and scope of this study is not large enough to generalize the findings here to the larger school setting. For the 2nd grade students of the school where this study took place however, I believe that a small group approach to instruction with texts at students’ instructional reading level is a more effective approach to instruction than whole group, teacher-lead instruction. This approach allows for more hands-on learning, more attention and focus on shy and easily distracted students, and allows teachers to provide immediate feedback regarding understanding of new skills.

References

Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., & Petrella, J. N. (2004). Effective reading comprehension instruction: Examining child x instruction interactions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 682-698. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.682

Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., & Underwood, P. S. (2007). A second chance in second grade: The independent and cumulative impact of first- and second-grade reading instruction and students’ letter-word reading skill growth. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11(3), 199-233. doi:10.1080/10888430701344314

Goddard, Y.L., Neumerski, C. M., Goddard, R. D., Salloum, S. J., & Berebitsky, D. (2010). A multilevel exploratory study of the relationship between teachers’ perceptions of principals’ instructional support and group norms for instruction in elementary schools. The Elementary School Journal, 111(2), 337-357.

LaRocque, M. (2008). Assessing perceptions of the environment in elementary classrooms: The link with achievement. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(4), 289-305. doi:10.1080/02667360802488732

McIntyre, E. (1992). Young children’s reading behaviors in various classroom contexts. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(3), 339-371.

Nicolae, M. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs as the differentiated instruction starting point: Research basis. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128, 426-431. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.182

Roy, A., Guay, F., & Valois, P. (2015). The big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept: The moderating role of differentiated instruction and individual achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 110-116. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.009

Şahin, A. (2015). The effects of quantity and quality of teachers’ probing and guiding questions on student performance. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 5(1), 95-113.

Smit, R. & Humpert, W. (2012). Differentiated instruction in small schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 1152-1162. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.003

Suprayogi, M. N., Valcke, M., & Godwin, R. (2017). Teachers and their implementation of differentiated instruction in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 291-301. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.020

Tieso, C. L. (2003). Ability grouping is not just tracking anymore. Reoper Review, 26(1), 29-36.

Tomlinson, C. A., Callahan, C. M., Tomchin, E. M., Eiss, N., Imbeau, M., & Landrum, M. (1997). Becoming architects of communities of learning: Addressing academic diversity in contemporary classrooms. Exceptional Children, 63(2), 269-282.

Topping, K. J., Samuels, J., & Paul, T. (2007). Does practice make perfect? Independent reading quantity, quality and student achievement. Learning & Instruction, 17(3), 253-264. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruct.2007.02.002

Valiandes, S. (2015). Evaluating the impact of differentiated instruction on literacy and reading in mixed ability classrooms: Quality and equity dimensions of education effectiveness. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45, 17-26. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.005

Wahlstrom, K. L. & Louis, K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 458-495. doi:10.1177/0013161X08321502

Walker-Dalhouse, D., Risko, V. J., Esworthy, C., Grasley, E., Kaisler, G., McIlvain, D., & Stephan, M. (2009). Crossing boundaries and initiating conversations about RTI: Understanding and applying differentiated classroom instruction. The Reading Teacher, 63(1), 84-87. doi:10.1598/RT.63.1.9

Appendix A

Characters/Challenge Graphic Organizer

2.RL.3: Describe how characters respond to major events and challenges

2.RL.3: Describe how characters respond to major events and challenges

Appendix B

Grading Rubric

2.RL.3: Describe how characters respond to major events and challenges

(Circle):

Pre Assessment

Formative Assessment

Guided Reading Groups: Level ______

Post Assessment

Score: _______/16

Appendix C

Fall 2018 NWEA MAP Reading Assessment Scores and Norm Achievement Percentile as compared with students’ peers nationwide

NWEA Norms Percentile Color Key:

Red: 1-20th Percentile

Orange: 21-40th Percentile

Yellow: 41-60th Percentile

Green: 61-80th Percentile

Blue: 81-100th Percentile

Please check the How to Motivate Your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Small Versus Whole Group Reading Instruction in an Elementary Reading Classroom

Kelsey Martinez, US ;Linda Plevyak, US