- Home

- Various Articles - Approaches in practice

- Developing Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric to Assess Secondary Students’ Text Review Competence

Developing Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric to Assess Secondary Students’ Text Review Competence

Intan Pradita, Ista Maharsi, and Irma Windy Astuti are lecturers in Islamic University of Indonesia. Intan and Ista are interested in critical language awareness, and Irma is interested in teachers education. Three of them have published their works in some international journals.

Abstract

Teaching critical reading skills for high school students struggling to read may be challenging yet assessing the learning process without rubric may even be a daunting task for teachers. Although concepts, trainings, and exposures are available, more practical and context-bound rubric for assessing critical reading skills are deemed urgent for teachers. This study is aimed to develop a critical reading assessment rubric for high school students, put it on trials, and measure it. Results show that the reliability and validity of the rubric is high and is able to help teachers elicit students' reasoning and evidences. However, as the scope of this study is limited, improving the rubric for better benchmarking followed by extensive rubric testing is of high priority for future research.

Introduction

Studies of critical reading practices in EFL context in the last decade have concerned more on instructional design and language devices (Emilia, Habibi, and Bangga, 2017; Kien & Huan, 2017; Pradita (2018); Pfelpsen, et.al., 2016; and Wallace, 2010). The findings of those studies have also suggested critical reading assessment mechanisms, yet, rarely do their developed taxonomy also provide the assessment tools along with their rationale. The presence of assessment tools would, among others, help school teachers to diagnose their students' current level of critical reading, and in so doing, become more capable of navigating their critical reading class. As with the practices of critical reading, especially in the context of EFL high schools, the trend seems to suggest their high demand implementation for the school-teachers and students (Kien & Huan, 2017). Floyd (2011) investigation, additionally revealed that the students especially of Asian cultures tend to lack of critical reading habit which among others, due to the teachers' traditional teaching. This relatively corresponds to the critical reading practices in Indonesian secondary schools, following the government policy on setting the standard of critical reading for high schoolers despite the teachers' focus only on teaching the knowledge basis rather than on literacy competence. The incompatilibity between the Indonesian government's High Order Thinking (HOTs) policy and the high school teachers's way of teaching was reflected in Emilia, Habibi, and Bangga's (2017) as it documented the struggling process of exposition text production, especially in employing textual resources, and cohesive links. The limited number of studies on the present day's HOTs implementation in Indonesian high schools is what concerns this study the most, particularly in the development of critical reading assessment tools.

This research is, thus, aimed to fill the void by proposing an assessment tool to assist high school teachers in Indonesia to assess their students' critical reading proficiency. The theoretical basis for the development of the assessment tool is based on two constructs. The first one is the text analysis construct adopted from the Register Analysis framework of Wallace (2010) which includes field, mode, and tenor of the discourse. The second construct is Wallace's (2010) and Floyd's critical literacy framework (2011) which cover biases, exploiting social messages attitudes, and digging opinions and values that are conveyed in a text were employed. One of the empirical study that employed Wallace's critical reading framework was Pradita (2018). Through integrating field, mode, and tenor analysis in reading a text, the students were observed to have more critical language awareness, especially in sensing the grammar.

Research design

A single development study was implemented in this study which includes analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate activities. This study took place in two senior high schools in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. A group of high achievers and those of mid achievers; 25 students of school A and 26 students of school B participated in this study. The observations were conducted twice during the analyze process and once in the try out process, whereas the teachers were interviewed twice in the analyze and tryout process. Thus, the teachers of both schools were serving as the study main participants as the users of the Critical Reading Inventory rubric developed for this study. The two teacher-participants were senior teachers who have been appointed as the provincial in-service teachers assessors. Two lecturers of reading subjects were, in the end involved, as the second raters to prevent biases in assessing the students' critical reading from the try-out session.The result of try-out session was used to measure the validity and reliability of the developed rubric. The Critical Reading Inventory rubric proposed by this study was created together with the questions. In this context, the rubric as a form of post-test was used. The text source was adapted from esl-lab.com while the core competence that was assessed was related to a language function of expressing invitation and giving opinion. The rubric is displayed below:

In the analysis, point four and five represented the assessment of critical literacy as suggested by Kien & Huan (2017), and point one to three represented the assessment of text analysis as critical reading proficiency. Point four and five were manifested in the scoring altogether with the aspects of field, mode, and tenor assessment. Based on the quantitative analysis, the validity of this rubric was considered as very high.

Research findings

Two recurrent themes, namely teachers' experiences before and after using Critical Reading Inventory (CRI) rubric and teachers' perception in using the assessment tool were identified from the interview and observation data. Both teachers of the two schools had attended critical reading workshops conduted by the government, and had also implemented critical reading activities in their classroom. In their verbal remark, ‘we stimulated the students not only to answer what questions, but also the why' (interview) was also proven during observation in which both teachers asked the students to make opinion upon their comprehension. In school A, the teacher was also seen assessing the reasoning based on true and false only. Whereas, in critical reading, the teacher should accept various answers that were supported with non fallacy(Wallace, 2010).

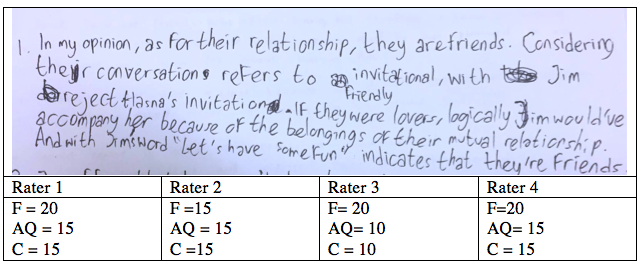

In school B, however, the teachers made an information gap discussion, to facilitate a group discussion. One's involvement and contribution in a discussion are of an important scaffolding to build critical literacy (Kien & Huan, 2017). However, the assessment of group discussion performance is more on how active the students raise their voices. It did not cover the quality of the arguments that were delivered. Whereas, the essence of critical reading and literacy is more on how to assess the arguments in a text, and the process of how readers found textual resources and linguistic features as evidences (Wallace, 2010; Emilia, Habibi, and Bangga's, 2017). There is a tendency that the teachers relied on the main reference that they got from the government's workshop. Neither extensive approaches nor theoretical basis of critical reading assessment provided by the teachers for making practical and easier to be taught. Below is the portrait on how the teachers and external raters use Critical Reading Inventory to assess the students' critical reading:

Finding shows that the rubric is helpful for teachers as the statistical analysis proved that the reliability score was α = 0.87 and the validity score was α = 0.892. The teacher of school B said that the rubric raised her view on critical reading, that it is not as simple as encouraging students to deliver opinion. She also said that she was benefited by her students' reading skill input. Before having the rubric, she said that it was difficult to assess the quality of arguments because most of her students have been able to deliver opinion and supported it with evidences. By using this rubric, she is able to assess the quality of the arguments. The teacher of school B said that the rubric was a bit difficult to use because it was very detail. In her school context, it required more time to assess into details. However, the rubric has made her to be more encouraging in making her students to be braver and explorative in delivering opinion. This is because her students tend to be reluctant to deliver opinion, let alone the evidences. They felt sufficient to just answer the comprehension questions.

Although the current study was conducted in Indonesia context, the findings have pedagogical implication for secondary school teachers' critical reading assessment mechanism. As traditional critical reading assessment tools focused on only the encouragement of being active in delivering opinion, the assessment on how qualified the opinion and its evidences were not provided. However this study provides evidences that the traditional assessment tools are not effective to support criticality in text analysis. It is more on stimulation of being active without considering the quality of the opinion. Therefore, by using this assessment rubric, the teachers are more stimulated to teach critical reading by providing more exposure on textual resources and knowledge on fallacy.

References

Emilia, Habibi, Bangga. (2017). An Analysis of Cohesion of Exposition Texts: an Indonesian Context. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(7), 515-523.

https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i3.9791

Floyd, C. B. (2011). Critical thinking in a second language. Higher Education Research and Development, 30(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.501076

Kien, L. T., & Huan, N. B. (2017). Teacher beliefs about critical reading strategies coin English as a Foreign Language Classes in Mekong Delta Institutions, Vietnam. European Journal of English Language Teaching, 2(4), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.816208

Pradita, I. (2018). Critical Language Awareness As Text-Mediated Language Analysis: Learners as Critical Readers. The Asian EFL Journal. 2(20), 97-109.

Pflepsen, A., Gove, A., Warrick, R. D., Yusuf, M. B., & Bello, B. I. (2016). Real life lessons in literacy assessment: The case of the early grade reading assessment in Nigeria. International Perspectives on Education and Society, 30(December), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-367920160000030011

Thomas, K., & Choi, M. (2017). Using multiple texts to teach Critical Reading skills to linguistically diverse students. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 32(03), 143–158.

Wallace, C. (2010). Critical Language Awareness: Key principles for a course in Critical Reading. Language Awareness, 8(2), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658419908667121

Please check the 21st Century Skills for Language Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website

The Big Picture of the Project-Based Approach (PBA) Language Learning

Mija Selic, SloveniaProblem-based English Language Teaching and Learning in Korea

Insuk Han, South KoreaDeveloping Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric to Assess Secondary Students’ Text Review Competence

Intan Pradita, Indonesia;Ista Maharsi, Indonesia;Irma Windy Astuti, Indonesia