Several Tips How to Avoid Teachers’ English Speaking Anxiety

Gabriela Mikulová is an English language teacher at the higher secondary school of information technologies in Slovakia. English language is a tool she uses every day, as well as, a field of study that she is absolutely dedicated to. The foreign language on one hand and language pedagogy on the other are the subjects that she is really trying to get better at by constant English language development.

Introduction

Living and working in the technically developed 21st century provides people of different countries with many advantages but, at the same time, forces them to fulfil certain requirements, too. From the point of view of education, it is definitely the demand to master at least one foreign language, giving the greatest preference to English, if learners are to become successful graduates and future employees, or even employers. Non-native speakers are, therefore, anticipated to reach the communicative competence of the foreign language and become fully-fledged and independent language users.

Due to that fact, a great pressure is put on foreign language teachers who have to rise to the challenge and realize their own potential to educate their learners in a way they will be able to use the language properly. The fact that non-native foreign language teachers are the learners of the language too is often forgotten though. On the basis of the research done to this issue (Horwitz, 1986, 1996; Kim and Kim, 2004; Mousavi, 2007; Yoon, 2012; Medgyes, 2017) it is proved that many non-native teachers often experience feelings of uneasiness, frustration, worry or anxiety when it comes to their teaching performance. What is even worse, problems of those teachers are often put aside or trivialized and they are forced to cope with their problems individually. However, when the problem is not to be solved, avoidance behaviour follows, having a negative impact on both teachers and learners.

What makes the situation even worse is the technically advanced age we are living in when learners have the direct access to spoken performance of native speakers and, therefore, are easily able to compare and contrast teachers’ languages abilities with those of native speakers. Subsequently, anxious teachers get under great pressure while learners do not hesitate to point out on their language imperfections.

Due to the above mentioned reasons, it is vital to deal with this issue to help language teachers cope with their anxieties, or even get rid of them. To contribute to the elimination of such negative experiences from the side of teachers, it is vital to understand the concept of anxiety in general, and to recognise the ways/activities of its handling.

Foreign Language Speaking Anxiety

When learning English or any foreign language (FL), learners often experience states of uneasiness, frustration, worry or fear due to the fact that they have to perform in something that is not natural for them. Generally, when experiencing such situations in the teaching-learning process, one of the possible reasons which makes mastering a foreign language difficult is “anxiety”, which has been a monitored and examined issue of learning foreign languages for a long time.

Anxiety, in general, can be defined as “the subjective feeling of tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry associated with an arousal of the nervous system” (Spielberger, 1983). Another definition explains anxiety as “a psychological construct, commonly described by psychologists as a state of apprehension, a vague fear that is only indirectly associated with an object” (Scovel, 1991, p. 18). Doubek and Anders (2013) define anxiety as a mental and physical state characterized by specific emotional, physical, cognitive and behavioural symptoms. It is an adaptive reaction which mobilizes the organism and helps it defend, attract or avoid an anxiety stimulus. The stimulus can be a previous external or internal antecedent or trigger. To state the definite causes of anxiety can be rather complicated as it is influenced by many factors – biological, psychological, social or other.

In the case of foreign language learning, it is the speaking skill which is widely considered to be the most troublesome for language learners. The same opinion is expressed by Horwitz (2001) who states that foreign language anxiety has been almost entirely associated with the oral aspect of language use while trying to identify more specifically the sources of anxiety as a recent trend. “Since speaking in the target language seems to be the most threatening aspect of foreign language learning, the current emphasis on the development of communicative competence poses particularly great difficulties for the anxious student” (Horwitz, 1986, p. 132).

The reason is simple. Speaking is a part of so called “productive skills” of a language which means that a learner has to individually and consciously produce the language in many different situations. From the point of view of teachers, speaking is an inseparable part of every lesson while it is the teacher who gives instructions, explains topics, performs discussions with students or conducts oral examinations. Speaking cannot be avoided during language classes because teacher serves as a model for his/her students as well. Anxious teachers are not able to fulfil their educational goals to the highest potential and “create” communicatively competent language users.

The fear of speaking in a foreign language may be related to a variety of complex psychological constructs, for instance communication apprehension, self-esteem or social anxiety and may affect an individual’s communication or willingness to communicate (Young, 1990). However, there can be also lingual factors, such as insufficient mastery of language systems and skills, which can initiate anxious feelings of a language user.

In fact, when we produce any fluent spoken performance, we have to think about every aspect of the language at the same time. We consider grammatical correctness, correct pronunciation, choice of words, coherence, context, appropriateness of opinions and other. Furthermore, we must not forget that spoken utterance is going on at certain pace, so we have to act immediately. In other words, we use and pay attention to all communicative sub-competences all at once. This is the reason why speaking is considered to be the most difficult skill for non-native learners of a foreign language and why this skill gives rise the most to unwanted feelings of anxiety.

Anxiety and non-native English language teachers

When thinking about the phenomenon of foreign language anxiety in a teaching-learning process, learners are almost automatically considered to be the objects being affected the most by its influence. This is confirmed by many studies (MacIntyre, Gardner, 1989, 1991; Young, 1990; Dewaele, 2002) which were aimed at learners, researching the sources, consequences, or ways of coping with their anxiety. Teachers are, however, equally involved in the process of education, and, as researches done to this issue (e.g., Kim and Kim, 2004; Yoon, 2012; Medgyes, 2017) have revealed, many of them suffer from the feeling of FLA when performing during the lessons.

Becoming a foreign language teacher does not mean that a non-native person, who had been a student of the foreign language until the time of his/her final exams, automatically becomes all-knowing source of information and master of systems and skills of the target language Despite teachers may have gained the appropriate proficiency level in a foreign language, they are still learners because language learning is a never-ending process (Horwitz, 1996). “It is almost impossible for even native speakers to know and teach everything there is to know about English. Therefore, foreign language teachers need to admit their limits and give up their ʻperfectionistʼ attitudes” (Kim, Kim, 2004, p. 178), which are often sources of their anxious feelings.

Horwitz (1996) proposed an interesting theory that language learners who sincerely want to learn a particular language may be more likely to experience anxiety than those who have no personal stake in the effort, because there must be a desire to communicate well in order to worry about how your communicative efforts are perceived. That idea about “omniscient teachers” is often widely advocated also by the public, students and teachers often not excluding, and puts even greater pressure on the self-evaluation of teachers.

The causes of teachers’ speaking anxiety are varied, but consequences are more or less the same. They may have a considerable negative effect on teachers and their learners, and this is why this issue should definitely not be overlooked.

Anxiety relieving strategies

In an effort to help teachers cope with their English speaking anxiety, several tips which are considered to be effective have been proposed. Due to the varied nature of individually perceived anxiety causes, the following strategies aim to cover not only lingual, but professional and personal aspects of teachers’ English language production, too.

Enhancement of English language skills and vocabulary

Receptive skills

Receptive skills, or skill by which learners “receive the language”, include listening and reading skills. Watching films, discussions, news, etc. can be equally included into the category of receptive skills while watching in EL primarily involves the listening skill which is further combined with the visual perception.

Many EL learners/teachers favour practicing receptive skills because it is often more accessible and more affordable than, for example, travelling to English speaking countries. Listening and reading activities are also highly preferred by introvert or highly anxious learners who do not like personal contact or face-to-face communication but who, at the same time, want to improve their EL skills. The last but not least advantage of receptive skills is that learners can rely on themselves. S/he does not have to look for a communication partner or travel anywhere. They can develop at their convenience. In the following lines, an overview of methods/activities developing receptive skills are provided:

Subtitled films

“Watching various programmes in English” is a factor of EL improvement which is frequently recommended by many English language learners. The film genre is not deciding, anyone can choose out of many options including films, TV series, discussions about different topics, interviews, news, documentaries, etc. Watching is even more beneficial when the learner selects a subtitled programme.

An EL learner should watch the film in the original (English) language with either English or L1 subtitles. There exist different opinions on which subtitles to select, thus, the learner decides. If actors’ spoken language is well understandable, it would be effective to choose English subtitles so that it enables learners to “hear and see” the word at the same time. If the understanding of the spoken performance is difficult, L1 subtitles might be selected. Anyway, this is still better option that to watch programmes which are dubbed.

Focused listening

When we listen to a radio programme, or watch the TV, we are engaged in one-way communication, thus, we can afford to devote all our attention to the form. Before we start listening, we can choose one type of language element to focus on, for example, verb tenses, phrasal verbs, conditionals or any other language point and we concentrate only on this aspect of the language.

Suppose it is adjective-noun collocations this time. Start listening and jot down every collocation as you hear it. At the end of the listening passage, your list contains, say, twelve collocations, such as remarkable progress, full rewards or worthy goals. Now, give an oral summary of the passage, using all twelve collocations on your list. Tick them off one by one after you have uttered them (a method proposed by P. Medgyes, 2017).

Reading aloud

Respondents agree that saying a language aloud can help us to decipher its meaning and use, to store it in our memory, and to improve pronunciation and intonation. As we read and speak at the same time, information is processed in two way sensory channels: seeing and hearing.

To use this strategy, a learner reads aloud a short article in English. After that s/he realises what was s/he paying attention to, the form, or rather, to the content. S/he reads the same text aloud a second time. S/he realises whether s/he was focusing on the same things. S/he reads it aloud a third time, but now gives special emphasis to certain linguistic features, such as vocabulary items, certain phonemes or sentence structure. After that, s/he puts the article aside. S/he asks her/himself whether s/he can summarise the gist of the article. Whether s/he remembers the unfamiliar word and expressions or whether s/he can recall the features which were highlighted (a method proposed by P, Medgyes, 2017).

Productive skills

The above mentioned (any many other) activities are effective when the learner wants to improve the EL skills on her/his own, however, it cannot be forgotten that the main objective of learning a language is communication. A learner is not able to master any foreign language without producing it. Due to that, practicing productive skills is of equal importance.

The ideal option is to communicate with native speakers due to their “genuine example” of the English production. Despite the undeniable effect of such communication, its ensuring does not have to be easy for every EL learner/teacher while they often lack time, finance and energy to travel abroad. They are too tired during holidays to travel abroad and it is rather complicated during the school year. Therefore, to enhance the speaking skill, an overview of activities/methods that can make practicing speaking more manageable is provided below.

Finding a communication partner

One of the possible ways is finding a partner who a teacher will communicate in English with. Ideally, the chosen person should be a native speaker. Nowadays, many schools employ English lectors to teach at particular schools for a certain time. If s/he is present at schools, it is very effective to spend as much time as possible with her/him and discuss various interesting topics. It can be beneficial twice while the teacher can learn much interesting information for further EL practice.

If the lector is not available, it would be effective to find an online native friend to communicate with. Social networks offer various learning groups where many native speakers are a part of. These days, many teachers also participate in Erasmus+ projects where they come into contact with many native speakers. To stay in contact with these people even after the project has ended is another possible way of maintaining communication in English.

If communication with a native speaker is not possible because of any reason, it is still possible to make an agreement with any other EL learner/teacher, family member or a colleague about mutual speaking in English. The condition would be that every time they speak to each other, the communication will be in English language.

The unsolicited interpreter

A genuine way of improving speaking skills is to work as a part-time interpreter. If this is not possible, language learners can interpret “uninvited”. The point of this activity is that the EL learner translates the speaker’s words in her/his head. It is not important to waste time looking for the most appropriate term or structure or miss a sentence or two, just to catch up as soon as possible. Getting tired after a few minutes should not be making the learner upset while even professional interpreters flake out after about half an hour.

The simultaneous interpreting can be done anywhere and anytime – at home by sitting in front of the television, during discussions with colleagues or friends or anytime the learner has the chance to do so (a method proposed by P. Medgyes, 2017).

Just a minute!

Many research participants emphasized the problem with fluent speaking often accompanied with lots of hesitation and long pauses. “Just a minute” is a well-known radio game (www.bbc.co.uk/justaminute) that helps to overcome these kinds of difficulties. The point is that you have to speak non-stop on a given topic for exactly one minute. During this time, you must not stammer, hesitate, repeat the same words and phrases, or deviate from the point. The learner finds an inspiring topic, gives her/himself thirty seconds to plan the speech, puts watch in front of her/him, takes a deep breath and begins. As soon as the one minute is up, stops. It can be particularly helpful to record the speech to realise the errors (a method proposed by P. Medgyes, 2017).

Recalling the day

When the teacher has some energy at the end of the day, s/he can practice recalling events that happened during the day. The point is that s/he summarises events of the day and translates them into English. As the learner thinks about particular situations, s/he tries to “think in English” and do it automatically.

This activity does not have to be done solely at the end of the day, the learner can adjust it to any situation. For example, when cooking, it is beneficial when you comment/think about everything you do – in English. It is advised to have a dictionary at your disposal to look for words you need at the moment. This activity can be transformed also into a written form in a way of writing a diary in English.

Vocabulary

The lack of appropriate vocabulary and difficulties to recall an appropriate word are another most frequently stated learners’ responses when dealing with causes and consequences of insufficient EL competence. Many of them highlight “reading in EL” as a source of new vocabulary enrichment and it definitely works. By reading in English, it is effective to use a notebook and write new words down, together with translations and illustrative sentences. Except reading, we consider quite effective to have this notebook constantly with you and every time you come into contact with an unknown word, write it down into the notebook. Everyday life offers many various situations that clear the way for vocabulary enrichment.

In the following lines, we present an overview of methods that might help EL teachers to systematically build their elaborate vocabulary system on.

Sticky notes

Sticky notes represent an effective method helping to learn words of objects around you. The point is that you write the name of a particular object on a sticky note and paste it on a real object. For example, when learning vocabulary concerning electronic devices, you write down the names of devices (kettle, dishwasher, curling iron, etc.) and stick them on those objects. This method is quite effective while you read the name of the object in English every time you use it. The only disadvantage is that you have sticky notes everywhere.

The Goldlist method

Goldlist method is considered to be an effective method of learning new vocabulary and everything you need is just a pen and a notebook. Machová (2019) explains the detailed procedure as follows:

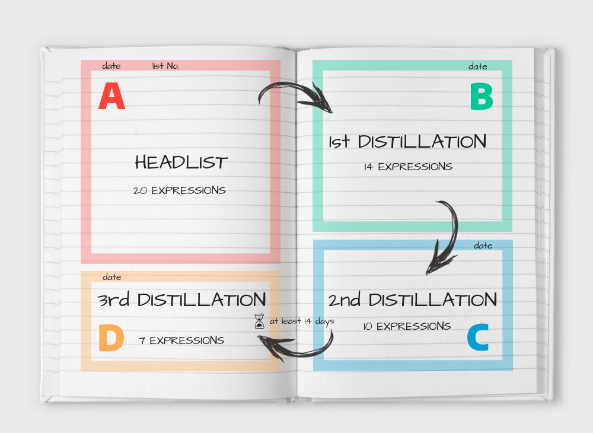

- Open a notebook and divide the first double-page spread into four sections – A, B, C and D in a clockwise direction, starting at the top of the left page. In the section A, write down today’s date followed by a list of 20 phrases you want to learn in one column and their translations in a second column, each phrase on a new line. This is called a “headlist”. Enjoy writing down interesting phrases and read every new phrase and its translation out loud slowly.

- Create a new headlist every day for the next 13 days only in section A of each new double-page spread. Don’t look at any of the older lists during these two weeks.

- Day 15: come back to the first headlist. Test yourself on how well you remember the phrases by covering up the column in your target language. You’ll be surprised to see that you remember about 30% of the expressions (6 out of 20).

- Copy the 14 phrases that you didn’t remember and their translations into section B on the opposite page. Remember to write down the date. That’s the first distillation. You won’t see these phrases for another two weeks.

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 for the second, third, and all other headlists, always making sure there are at least two weeks between rewriting the forgotten phrases from section A to section B.

- Day 29: come back to the first double-page spread and test yourself on the 14 phrases in section B. Again, you’ll have remembered about 30%. Copy the rest (10 words) in section C below and include the date. Read them aloud, and that’s it. You just made the 2nd distillation!

- Repeat this process every day with all sections: keep writing new headlists (section A) and test yourself on previous headlists and distilled lists in all sections, always at least 14 days after you wrote them. That’s why it’s important to date each list.

(adapted from Machová, 2019)

The Goldlist method is well known and considered to be effective by many students and teachers, too. A few participating teachers recommended it as a factor that had helped them to learn and remember new vocabulary. Teachers who would like to know more details about this method can get a free detailed e-book called Goldlist Method In a Nutshell (available at: www.languagementoring.com/goldlist).

The card file system

Within this method, which is aimed at vocabulary learning and retention, learners choose a text and underline or highlight as many useful words and expressions as they wish to learn. They should give priority to those items which appear to be the most relevant and do not break the flow of reading.

After that, learners look up the meaning, usage and pronunciation of each unfamiliar item. They should use dictionary or reference books available. Each new item is written down on a separate card, should first be registered in isolation, then in the sentence in which it originally occurred and one further model sentence from the dictionary to exemplify the usage.

Subsequently, learners should make conscious effort to memorise the items and build them into their active vocabulary. When plenty of sets have been collected, they should be rearranged according to new criteria, such as:

- parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.),

- topic areas (transport, shopping, illness, etc.),

- recall difficulties (“I simply cannot remember this word!”),

- frequency.

Learners should have these sets within easy reach, browse through them whenever an opportunity arises and continually eliminate those items that can already be used in speech. There exist several ways of manipulating the card file system or cards can be substituted by an easily portable notebook (a method proposed by P. Medgyes, 2017).

Professional and personal growth

Mastering the EL skills and vocabulary is very important if a learner wants to gain the language foundations, however, it just one step in overcoming unwanted anxiety experience. To become more self-confident and a balanced teacher, the one must develop her/himself both professionally and personally. In this subchapter, we would like to offer strategies and advice for EL teachers hoping that they will inspire and enable them to see the problem from a new/motivating perspective.

Language conferences and workshops

Language conferences represent an amazing way how to actively keep in contact with English language and grow professionally at the same time. Many universities organise together with various organisations (the Chamber of English Language Teachers, Macmillan Education, Oxford University Press, etc.) many interesting conferences and workshops on English language, methodology, or other pedagogical issues.

Conferences are held in the English language and it is important to register in advance. Teachers can participate individually or with friends/colleagues. Besides gaining useful knowledge, teachers can also buy various books, dictionaries, visuals, etc. that will help them during teaching. Attending conferences is enormously motivating and after it has finished, you will feel an inner desire and strength to work on yourself even harder.

English language setting

Another effective way of how to stay in a contact with English is becoming a member of EL groups on social sites (English is fun, BBC English, Learn English, etc.) which offer an amount of EL vocabulary, often visualised in a very attractive and rememberable way. Grammatical structures are often included and made into easily understandable notes as well.

Teachers can follow also various web pages dealing with EL topics/education (SCELT, various blogs, etc.). Authors publish interesting and enriching articles for teachers and EL learners. Joining these groups is another way how to improve English and learn something new.

Constant preparation for lessons

Despite the fact that many methods can help teachers to be more engaged with English, the most precious advice how to reduce anxious feeling during teaching practice is still constant preparation for every single lesson. When teachers make a plan of the lesson, visualise it and study all the materials in advance, it makes them feel prepared and the possible situations that can surprise them during the lesson are significantly lowered. Constant preparation for lessons requires teachers’ after-work time, however, plays an important role for their professional and personal well-being and, therefore, is worth spending the time.

Anxiety-relieving strategies

If no one from the above mentioned strategies brings sufficient satisfaction, trying various anxiety-relieving strategies can be an effective way for feeling balanced during English teaching. Teachers may search the Internet and look for some that they favour or they might make an appointment with a psychologist who will introduce them into the issue. It is important to realise that searching for help is not embarrassing, but exactly the opposite. It is an effective step in becoming mature, both personally and professionally.

Body posture – “power poses”

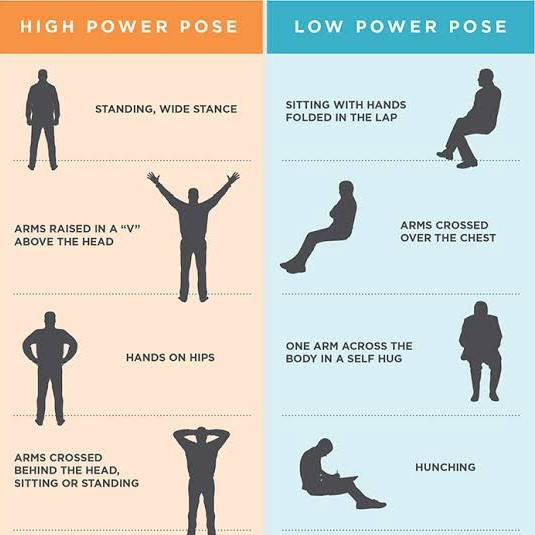

The way in which the teacher moves and uses the body language is, on one hand, characteristic to every single person, on the other, it can reveal a lot about her/his actual state or condition. Very interesting findings about the effect of the body posture were discovered by the Harvard professor A. Cuddy (2013). She argues that one’s body postures are able to change not only how other people perceive us, but can influence how we perceive ourselves as well. She termed them “power poses” and, as she further explains, they can change even person’s body chemistry. These changes subsequently affect the way a person does her/his job and interacts with other people. Below, we enclose a picture that illustrates “high power” and “low power” poses. Poses in which a person is “opened-up” demonstrate the “high power” poses and vice versa, when a person feels feeble and helpless, s/he “closes up” or wrap her/himself (Cuddy, 2013).

(adapted from Huizer, 2019)

Her research showed interesting and surprising findings. After just a two-minute “high power pose” the risk tolerance of a person soared and the risk tolerance of “low-power posers” shrank. The research found a profound change in a body chemistry. Testosterone, which is a “dominance” hormone, rose 20% in the case of “high-posers” after a mere 2-minute pose. The other hormone is cortisol. When cortisol levels drop, people are better able to handle stressful situations. Findings showed that after the 2-minute poses, the cortisol levels of the “high power” group fell sharply and vice versa, cortisol levels of “low-power posers” rose (Cuddy, 2013).

These are remarkable findings which can be considerably beneficial for teachers. As teachers stand or sit in front of their learners who observe their body language all the time, we consider “power pose” findings greatly important to know and practice. We recommend teachers to try to consciously influence their body poses in an effort to lower the unwanted feelings they experience during lesson with their learners.

60 seconds of good news

The first couple minutes of a new class can be the most intimidating part of the lesson. A good way how to get rid of unpleasant anxious feelings is to start the lesson with a ritual of 60 seconds of good news. During this time, students report birthdays, new cars, successful surgeries or other positive experiences. Besides students can talk about things/experiences they are proud of, the spotlight is on students and the teacher has more time to adapt to the conditions (Finley, 2017).

All of the above mentioned strategies/methods should serve teachers to make their anxiety experience more bearable, or potentially contribute to the absolute deprivation of anxiety. Due to the fact that anxious feelings can be caused by either lingual or externolingual factors, we provided an overview of strategies facilitating both of them. We must emphasize that given strategies represent just a selection of opportunities that we consider to be substantially effective. There exist many other methods that can be individually more effective than those described in this study.

Except proffered methods and strategies, we would like to emphasise that it is inevitable to create specialised courses or training within the university preparation of future EL teachers that would adequately prepare pre-service teachers for the possible mental strain that is to be experienced during performing their profession. Such support would definitely be priceless for in-service teachers as well, and would show teachers how to effectively cope with/overcome the anxiety experience and feeling of uneasiness.

To conclude, every teacher should find the right strategy/ies that will work for her/him the best. Getting rid of anxiety can be a highly individual process and what works for one, does not have to work for the other. However, finding the right way how to feel balanced is inevitable if teachers want enjoy their personal and professional growth which will be subsequently mirrored by the pleasure of seeing their students’ progress. And that is something worth experiencing…

References

CUDDY, A. (2013). This Simple ʻPower Pose’ Can Change Your Life and Career. [online] [cit.23.05.2020] Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/power-pose-2013-5?op=1.

DEWAELE, J. - M. (2002). Psychological and sociodemographic correlates of communicative anxiety in L2 and L3 production. International Journal of Bilingualism, Vol. 6 (1): 23-38. ISSN 0367-0069.

DOUBEK, P., ANDERS, M. (2013). Generalizovaná úzkostná porucha. Praha: Maxdorf. ISBN 978-80-7345-346-6.

FINLEY, T. (2017). 9 Tips for Overcoming Classroom Stage Fright. Edutopia. [online][cit.23.05.2020] Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/blog/overcoming-classroom-stage-fright-todd-finley.

HORWITZ, E. K., HORWITZ, M. B. & COPE, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 70, No. 2, 1986. pp.125-132. 0026-7902/86/0002/125.

HORWITZ, E.K. (1996). Even Teachers Get the Blues: Recognizing and Alleviating Language Teachers՚ Feelings of Foreign Language Anxiety. Foreign Language Annals, 29, No. 3.

HORWITZ, E. K. (2001). Language Anxiety and Achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.: vol. 21. pp. 112- 126. 0267-1905/01.

HUIZER, E. J. (2019). Be Confident and Win with these Power poses. Medium. [online] [cit.21.05.2020] Available at: https://medium.com/@ericeelde/be-confident-and-win-with-these-power-poses-754106b0e303.

KIM, S-Y., KIM, J-h. (2004). When the Learner Becomes a Teacher: Foreign Language Anxiety as an Occupational Hazard. English Teaching, Vol. 59, No. 1.

MacINTYRE, P. D., GARDNER, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and Second-Language Learning: Toward a Theoretical Clarification. A Journal of Research in Language Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 251-275. 1989. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00423.x.

MacINTYRE, P. D., GARDNER, R. C. (1991). Investigating Language Class Anxiety Using the Focused Essay Technique. The Modern Language Journal, vol. 75. pp. 296-304. ISSN 0026-79 02/ 9 | /0003/ 296.

MACHOVÁ, L. (2019) The Goldlist method: Learning vocabulary by writing it down. The Open University, 2019. [online] [cit.18.05.2020] Available at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/languages/learning-languages/the-goldlist-method.

MEDGYES, P. (2017). The Non-Native teacher. Surrey: Swan Communication Ltd.. ISBN 978-1-901760-11-8.

MOUSAVI, E. S. (2007). Exploring՚ Teacher Stress՚ in Non-native and Native Teachers of EFL. ELTED Journal, Vol. 10.

SCOVEL, T. (1991). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. In E. K. Horwitz, & D. J. Young (Eds.), Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implications (pp. 15–24). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

SPIELBERGER, C. D. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

YOON, T. (2012). Teaching English thought English: Exploring Anxiety in Non-native Pre-service ESL Teachers. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 2, no.6. ISSN 1799-2591.

YOUNG, D. J. (1990). An Investigation of Students՚ Perspectives on Anxiety and Speaking. Foreign Language Annals, vol. 23, no. 6.

Please check the Pilgrims courses at Pilgrims website.

What Motivates Slovak Students to Become English Teachers?

Elena Kovacikova, Nitra, SlovakiaSeveral Tips How to Avoid Teachers’ English Speaking Anxiety

Gabriela Mikulová, SlovakiaThree Letters to My Teachers

Jana Chynoradska, Slovakia