Comparing the Rate of Vocabulary Growth

Allison Garrett, M.Ed. is a teacher at Louisa Wright Elementary School, Lebanon, Ohio, USA. Her focus is on supporting English language learners (ELL) in the preschool classroom. E-mail: agarrett@springboro.org

Linda Plevyak, PhD. is an associate professor in the Curriculum and Instruction Program at the University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Her research focuses on testing teaching methodologies that support the development of critical thinking skills. E-mail: linda.plevyak@uc.edu

Comparing the Rate of Vocabulary Growth in Students who are English Language Learners in the Preschool Classroom

Abstract

This study looks at the growing population of students in the United States whose native language is not English. These students are learning to speak English in parallel to the school curriculum and are often referred to as English Language Learners (ELL). ELL students need a great deal of support to reach literacy and language goals and to be successful in school. Studies have shown that preschool programs rich in vocabulary help to support these students (Uchikoshi, 2006). The current study uses the Get it, Got it, Go assessment to compare vocabulary growth in both English only (EO) and ESL (English as a second language) students in the preschool classroom. The current study looks at vocabulary development over a five-month period in preschool students. The study compares students who speak English as their native language, and English language learners. The findings from this study are consistent with the studies reviewed that showed ELL students increase their vocabulary when first immersed in school.

Introduction

The population of young English Language Learners (ELL) in preschool classrooms around the United States has grown significantly over the last several decades. During the 1990s minorities made up 80% of population growth in the United States (Brice, O’Hanlon, & Roseberry-McKibbin, 2005). It is the role of an educator to be prepared to teach all students who walk in the door, and it is very clear that the population of students is shifting towards a more diverse student group from all around the world.

Students are entering schools across the country with different histories, languages, and cultures, and therefore what teachers are teaching and how they interact with students should also be shifting. Teachers need to address a culturally diverse classroom through varying learning experiences that can be understood by all students. The population of English Language Learners (ELL’s) in schools has increased by 60% between 1994-2005 (Halle, Hair, Wandner, McNamara, & Chien 2011). While the population of ELL learners is diverse, the majority of ELL students in America are from homes that speak Spanish.

Around 30% of head start students and 25% of public school preschool students in America are Hispanic (Barnett, 2007). Many factors contribute to school readiness in ELL students (Halle, et al., 2011). The number of Limited English Proficient (LEP) students has been growing in the last two decades as well. Verdugo and Flores (2007) found in their research that there is an achievement gap between LEP students and English only students in the areas of speaking and writing in English. They looked at four important factors that play into this deficit. They are School Capacity, Teacher Preparation, Testing, and Language Acquisition. The current study will be focusing on language acquisition in relation to achievement.

Literature review

Implementing differentiated instruction is important in any classroom, but is vital when working with ELL students. Like all students, English learners need a range of experiences that are both challenging and achievable. Using a child’s native language as part of the instructional method is very beneficial (Verdugo, 2007). If a student has become proficient in their native language, it will be much easier to transfer that skill to English in a classroom setting.

Researchers have also studied the transfer of vocabulary from Spanish to English in kindergarten students. One study found that there was a positive correlation in skill level across languages (Atwill, Blanchard, Gorin, Herman, & Christie, 2010). Phonemic awareness is a large precursor to reading and overall success at school. An ELL student who has weak phonemic awareness skills in his native language may have a harder time learning English than his ELL peer who has mastered these requisite skills in his first language. Some schools have addressed this issue by giving preschoolers a bilingual education. Students in one study showed that receiving a bilingual preschool education helped students gain English skills as quickly as their peers enrolled in an English only program, while maintaining skills in Spanish (Restrepo, et al., 2010).

Studies have also been completed to show the importance of early education for vocabulary development in all children, both native English speakers and ELL children (Uchikoshi, 2006). Uchikoshi (2006) states that a strong vocabulary in one’s native language is a predecessor to vocabulary development in a second language. Uchikoshi also found that many preschool experiences, including watching educational programs on television, contributed to vocabulary growth in ELL students. It was shown to be important for there to be repetition and reinforcement of new vocabulary introduced on TV shows. Uchikoshi also found that ELL students who attended a preschool program entered kindergarten with a larger English vocabulary then children who stayed home the year prior to kindergarten.

Barnett (2007) looked at English and Spanish speaking preschool children who were enrolled in two different programs. The first program was a bilingual classroom where instruction was given in both English and Spanish, and the second being an English immersion classroom that provided instruction in English only. This study looked at vocabulary and early literacy development for both the Spanish speaking and English-speaking students. Both groups increased their English vocabulary scores significantly from fall to spring, and both programs were shown to be effective in teaching early literacy skills and vocabulary. However, the bilingual classroom improved vocabulary and literacy in Spanish as well, whereas the gains seen in the English emersion classroom were seen primarily in English (Barnett, Yarosz, Thomas, Jung & Blanco, 2007). Both groups of students gained skills in English at the same rate. The bilingual classroom saw improvements in Spanish alongside the gains seen in English. This study shows the importance of early education for students who are learning English, and also shows the benefits of a bilingual classroom, without hindering English learning.

It is clearly important for English learners to become proficient in conversational and academic English to be successful in school. It has also been shown that the earlier a student becomes English proficient, the better his social and cognitive outcomes (Halle, et al., 2011). Students who are immersed in language rich programs before kindergarten have a better chance of being successful in school. These programs prove to be important for ELL children in cognitive and language development (Halle, et al., 2011). Important skills that should be taught in the preschool setting include phonemic awareness, vocabulary development and expression. These skills are vital to reading success, and are stepping stones that many ELL students come to school missing.

Farnia and Geva (2011) have researched the importance of vocabulary development in young ELL students. Students who do not speak English at home are more likely to enter school with limited English vocabularies, and it is difficult for them to catch up to English speaking peers. Farnia and Geva (2011) looked at the connection between student’s vocabulary and their memory and found links between early vocabulary and short-term memory for both English only (EO) and ELL students. Students’ phonological short-term memory was tested using nonsense words that students were asked to repeat. There were questions regarding the “word likeness” of the nonsense words used to test short-term memory that may favor English only, or more English proficient ELL children. To minimize students’ ability to pull sounds from the English language in their study, Farnia and Geva (2011) used nonsense words that were different from word formations common to English. This study found that the cognitive processes are the same for all students (EO and ELL) in developing vocabulary.

Even if students come to school with limited English vocabularies, they can use the same cognitive processes used to learn their native language to learn English. They may learn English at a quicker rate if they have strong language skills in their native language. Researchers also found that the gap in vocabulary development between ELL students and EO students did not close during their six-year study. ELL students showed a steeper rate of vocabulary development in early grades, but slowed down in upper elementary. Their steep rise in early grades may be due to the fact that many ELL students are immersed in English in a systematic manner, not having much introduction to English prior to coming to school (Farnia & Geva, 2011). EO students come to school already familiar with the English language, and in many cases, familiar with English in print. The ELL students may show a steeper rate of vocabulary at first, but they are starting out far behind their EO peers. If these ELL students are exposed to English in the school setting at a younger age, such as within a play based preschool, there is more time to close that gap of achievement and language. Farnia and Geva (2011) did not look at students who are at preschool level (age 3-5).

Masoura and Gathercole (2003) looked at long-term effects of vocabulary development as linked to short-term memory and long-term knowledge. Students in this study that scored higher on the English vocabulary section also scored higher on learning tasks. This study was done with elementary students over several years and showed that learning performance improved with vocabulary growth, but not with “non-word repetition ability” (Gathercole, 2003, p.426). This may explain why ELL students did not catch up to their peers despite short-term memory skills in the study by Farnia and Geva (2011). They could repeat the nonsense words, but were not gaining vocabulary at the rate needed.

Restrepo and Towle-Harmon (2008) looked at the importance of a preschool education for ELL students in order to close the literacy gap in later years. The researchers found that ELL students often do not develop phonemic skills as quickly as their English-speaking peers unless they have had the proper exposure and instruction in early classroom experiences. Given these skills, ELL students can transfer them between languages and an important reason why students should maintain their native language. Skills picked up at home in their native language can transfer to learning English. Many important skills are being developed in the preschool years, and an education that supports learning a new language while maintaining the native language is imperative. Halle emphasizes the importance to maintaining ones home language to help students understand cultural identity and feel like they belong to a group of people.

When an educator shows respect and value for students’ cultures, students will feel safe and can focus on learning in the classroom. Restrepo and Towle-Harmon (2008) looked at four domains that contain the skills that can help an ELL student become successful: print knowledge, phonological awareness, writing, and oral language (Restrepo, 2008). These skills, coupled with native-language skills, will help predict reading achievement in future grades. The authors also reiterated the importance of a strong relationship between home and school to foster early literacy skills in young children. Parents can help schools to value their native language while learning a new one, and can reinforce skills at home (Restrepo, 2008). Screening early literacy skills in both ELL and EO students can help to identify students that need intervention in these vital pre-reading skills (Farver, Nakamoto, Lonigan, 2007).

The current study looks at students who are enrolled in an English immersion preschool with English only and ELL students. The purpose of this study is to determine if ELL students are gaining vocabulary at the same rate as their EO speaking peers.

Method

Participants

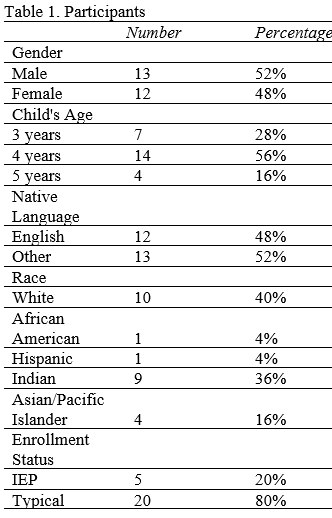

Twenty-five students in a Southern Ohio (United States) preschool participated in this study. The participants included 12 girls and 13 boys and their ages were (7) three year olds, (14) four year olds, and (4) five year olds. Thirteen students came from homes where the native language was different than the language spoken at school (English). Of the thirteen ELL students, 4 (30%) of them spoke English at home at least 50% of the time. The participants are summarized in table one.

Measures /Materials

The parents of the preschoolers filled out a family home language survey (see Appendix). Questions were adapted from multiple surveys on www.matsol.org and were reviewed by a committee before being sent home. The survey asked parents the native language of the parents and the child. It also asked what language was spoken at home and with friends. The last survey question asked what percentage of the time English was spoken at home. Parents were asked if English was spoken more or less than 50% of the time at home.

The preschool students were tested using the Get it, Got it, Go (GGG) assessment tool. The GGG is a standardized assessment tool that measures individual and growth indicators needed for literacy success. The test is designed for preschool students age three to five. The three indicators that the assessment looks at are picture naming, rhyming, and alliteration. These skills are important indicators to predict success in literacy development. For the current study, the picture naming section of the assessment was used. The picture naming assessment contains 96 picture cards that are shuffled and put in random order for each student. Students are given one minute to name as many pictures as they can. There are specific guidelines when administering the assessment and a training that all assessors are required to take prior to administering the GGG. For this study, the assessor was fully trained and administered all of the tests.

Procedures

Questionnaires were sent home to parents with a cover letter that included an explanation of the research and the GGG assessment that was going to be administered. Once surveys were returned, students were assessed. The assessment took place in a quiet room or in the hallway where there were minimal distractions. Students were tested individually. Before assessing, students were introduced to the assessor and were asked a few general questions to build a rapport and put students at ease.

The administrator began by showing and labeling four practice pictures. Students were then shown the same four pictures and asked to label them as the assessor had. All students were able to label the four practice pictures (apple, baby, bear, cat). A timer was set for one minute and students named as many pictures as they could in that minute. If students did not know the name of a picture or said the wrong name, the assessor moved on to the next picture. All students received a sticker after the assessment and went back to their classroom. Students were assessed in the fall to establish a baseline, and then assessed again after 5 months of instruction to measure their improvement.

Research findings

The two main variables of this study were native language of the students and the language spoken at home. A statistical analysis was done to compare English-only (EO) students with students who were English language learners (ELL) who spoke English as a second language.

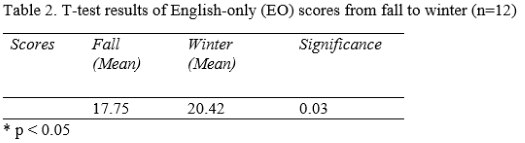

The mean score of all English-only students in the fall was 17.75. The mean score of these same students in the winter was 20.42. The means were significantly different as confirmed by a paired student’s t-test. Average scores for English-only students went up 15% from fall to winter. Of the twelve EO students assessed, two of them had the same scores in the fall and the winter and one student’s score went down one point. The other nine students saw increases ranging from one to eight points (table two).

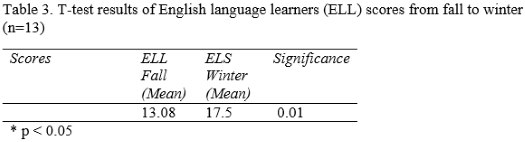

The mean fall score for the English language learners was 13.08. The mean winter for these same students was 17.5. ELL scores went up 33%. The means were significantly different as confirmed by a paired student’s t-test. Twelve of the thirteen ELL students given the GGG assessment saw an increase from fall to winter scores (table three).

Although the mean scores for the ELL students were not as high as the EO group in either testing time (EO fall- 17.75, EO winter- 20.42, ELL fall- 13.08, ELL winter- 17.5), the ELL scores went up more over the five months than the EO scores. This is consistent with research completed by Farnia and Geva (2011), which shows that ELL students will gain vocabulary at a faster rate in their first years of school. Though, other studies have shown that ELL students may never close the gap and reach their peers scores over the course of the school year. The current study shows similar results as the ELL students’ scores increase, but do not increase enough to be the same as their English Only peers.

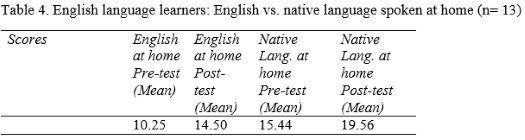

A comparison was also completed on ELL students who spoke English vs. their native language at home. Students were broken into two categories. Students whose parents stated that English was spoken at home more than 50% of the time and students with parents who stated that their native language (other than English) was spoken at home more than 50% of the time. Four out of the thirteen ELL students tested speak English at home more than 50% of the time, while 9 of the students speak their native language more than 50% of the time. The average winter score of students who speak English at home more than 50% of the time had a mean score of 14.50. Students who speak their native language more than 50% of the time had a mean score of 21.75, which is a 7.25 difference. These scores confirm the importance of continuing to speak ones native language while learning a new language.

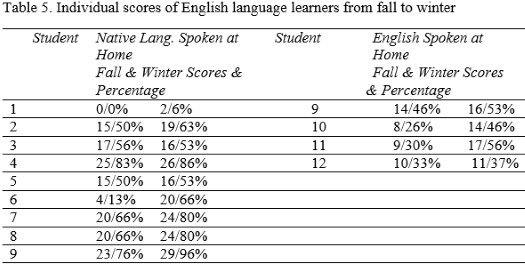

Table four looks at the ELL students tested in this study. Columns 1 and 2 look at students who speak English at home more than 50% of the time. Columns 3 and 4 represent students who speak their native language at home more than 50% of the time. As you can see both groups gained an average of 4 points on the assessment, but the students who speak their native language at home more than 50% of the time had pre- and post scores that averaged five points higher then those who speak English at home more than 50% of the time.

Table five looks at individual scores of students’ progress. Only four of the thirteen families stated that they speak English more than 50% of time at home, so there is limited data in this study to validate the importance of speaking ones native language for vocabulary development. This small sample does support research done by Uchikoshi (2006) that found that students learn the vocabulary of a new language at a quicker rate if they are speaking their native language at home, using proper grammar and structure. After interviewing the teachers of these four students, they all said that in interactions at school the parents’ of these four students were difficult to understand when speaking English and not as proficient as when they spoke to their child in their native language in three out of four cases. If students are hearing broken English on a regular basis before coming to school, it may take more time to develop early literacy skills. The four students who speak English at home more than 50% of the time, had score increases ranging from one to eight points (1, 2, 6, 8). Of the nine students who speak their native language 50% of the time or more, one student went down one point from the pre to post-test and the other eight went up ranging from one to sixteen points (-1, 1, 1, 2, 4, 4, 4, 6, 16).

There were five students on IEP’s, or individual education plans, who receive special education support that participated in this study. Two were in the ELL category and three were in the EO category. IEP students scored an average of 14 on their fall assessment and 17.2 on their winter assessment. Their scores were slightly lower then their typical peers who scored an average of 18 in the fall and 20.80 in the winter.

Conclusion

The findings described here are consistent with the studies reviewed that showed ELL students increase their vocabulary when first immersed in school (Uchikoshi, 2006). This could be due to the fact that preschool aged children are constantly learning new information through experience and play. It is unfortunate that studies show these students may never catch up to their EO peers. This current study showed an increase in vocabulary for ELL students from fall to winter by 33%, which is significantly more than the 15% improvement for EO students. The students receiving special education saw scores increase by 23%. These findings show that ELL students saw the largest percent increase (33%) as a group.

These findings coincide with the research of Restrepo and Towle-Harmon (2008), which show ELL students gaining rapid vocabulary development when first immersed into an English-speaking school program. The students in the current study were younger than the ones in the Restrepo and Towle-Harmon (2008) study and they would have more time to catch up with EO peers and be successful students in language and literacy.

Teachers can use the results of this study and take action with their ELL students. By creating experiences that will build language skills and confidence in students, teachers are preparing them to be better readers, writers, and students in general. The growth indicators targeted in the Get it Got it Go! Assessment can be used to project a plan for the classroom based on students’ needs. If students have poor vocabularies then teachers should label classroom items and surroundings. Teachers should read stories that are vocabulary rich and that clearly teach simple words needed to build upon to create larger, more intricate vocabularies.

Recommendations/ limitations

This study supports the idea that educators should provide a vocabulary rich environment that will support learning for all students. Students who are not English proficient can gain skills quickly in an environment that supports language skills including pre-reading, writing, and conversational skills. Vocabulary development is directly linked to language and literacy, and therefore is vital for school success. Labeling objects with pictures and words, reading literacy rich texts, and participating in meaningful conversations will build vocabulary in young children. By allowing students to interact with peers and model vocabulary rich conversations, educators can help students from all backgrounds build a larger vocabulary.

The current study does present several limitations. There are many variables in the small test group, including language discrepancies, age differences, gender issues, and diversity of family backgrounds. The students in the study came from two different school districts. These two school districts were used due to the fact that their programs had the largest numbers of ELL students in the area. The varying intelligence of the students’ was probably the biggest variable that we were unable to test. Student’s IQs were not tested, as IQ scores are not as accurate in students under the age of seven. We also did not look at socioeconomic status, years in the United States, or number of siblings. All of these factors have an effect on students and their language development. Future studies could assess intelligence to see how it affects vocabulary development in children.

Refernces

Atwill, K., Blanchard, J., Gorin, J.S., Herman, S., Christie, J. (2010). English-Language Learners: Implications of Limited Vocabulary for Cross-Language Transfer of Phonemic Awareness With Kindergartners. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 9(2), 104 – 129.

Barnett, W. S., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Jung, K., & Blanco, D. (2007). Two-way and Monolingual English Immersion in Preschool Education: An Experimental Comparison. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 277-293.

Farnia, F., Geva, E. (2011). Cognitive Correlates of Vocabulary Growth in English Language Learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(4), 711-738.

Farver, J. M., Nakamoto, J., & Lonigan, C. (2007). Assessing Preschoolers' Emergent Literacy Skills in English and Spanish with the Get Ready to Read! Screening Tool. Ann. of Dyslexia, 5, 161-178.

Halle, T, Hair, E., Wandner, L., McNamara, M., & Chien, N. (2011). Predictors and Outcomes of Early Versus Later English Language Proficiency among English Language Learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(1), 1-20.

Masoura, E.V., & Gathercole, S. E. (2003). "Contrasting Contributions of Phonological Short‐term Memory and Long‐term Knowledge to Vocabulary Learning in a Foreign Language". Memory (Hove), 13(34), 422-429.

Restrepo, M. A., Towle-Harmon, M. (2008). Addressing Emergent Literacy Skills in English-Language Learners ASHA Leader, 13(13), 10.

Restrepo, M. A., Castilla, A.P., Schwanenflugel, P.J., Neiharth-Pritchett, S., Hamilton, C.E., Arboleda, A., (2010). Effects of a Supplemental Spanish Oral Language Program on Sentence Length, Complexity, and Grammaticality in Spanish-speaking Children Attending English-only Preschools. Language, speech & hearing services in schools, 41(3).

Roseberry-McKibbin, C, Brice, A., O’Hanlon, L. (2005). Serving English Language Learners in Public School Settings: A National Survey. Language, speech & hearing services in schools, 36(1), 48-61.

Uchikoshi, Y. (2006). English Vocabulary Development in Bilingual Kindergarteners: What are the Best Predictors? Bilingualism (Cambridge, England), 9(1), 33-49.

Verdugo, R., Flores, B., (2007). English-Language Learners: Key Issues. Education and Urban Society, 39(2), 167-193.

Appendix

The following form was sent to families to screen for ESL students. All families who participated in the current study completed it.

Student Name:_______________________ Teacher Name: __________________

***** Return by Monday January 23rd to your child’s teacher *******

- What is the native language(s) of each parent/guardian?

______________________ Mother

______________________ Father - What language did your child first understand and speak?

- Which other languages does your child know?

- What language does the family speak at home most of the time?

- What language does the child speak to her/his friends most of the time?

- Please check one of the following:

_____________English is the only language spoken in our home.

_____________A language other than English is spoken in our home less than 50% of the time.

_____________A language other than English is spoken in our home 50% of the time or more.

Second language spoken in the home is _____________________________. (Please list the dialect you speak, where applicable.)

![]()

Please check the Methodology and Language for Kindergarten course at Pilgrims website.

Comparing the Rate of Vocabulary Growth

Allison Garrett and Linda Plevyak, USConsciousness-raising Approach in ELT Classroom

Mahshad Tasnimi, IranExperiential Listening

Michael Tooke, ItalyInvestigating EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on the Importance and Barriers of Professional Development

Zeinab Sazegar and Khalil Motallebzadeh, IranThe Map Is Not the Territory. The Cartographers, the Humans’ Territories, and the Dragons’ Territories

Gabriel R. Suciu, RomaniaWorking With Mixed Ability Adult Classes

Serafina Filice, Italy