Working Through Paths

Daniel Costa has worked as a corporate online language educator for Woospeak for more than a decade, teaching mainly English but also Portuguese, Italian and Spanish to learners from several fields and countries. A regular MET contributor, he has written for publications such as the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, Encyclopaedia Britannica and academic journals. He has a CELTA, a BET, a COLT, an MA in History (Birmingham), an MA in ELT (Southampton) and a BA in Philosophy (London). He is currently doing his PhD in history at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, a multilingual project related to scientific knowledge during the spice trade. Linkedin profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/danielcostaeducator/

Introduction

Which features of literary practice can foster meaningful interaction between writers and their readership? While unfamiliar to many, ergodic literature is characterised by strategies which have been used by a number of writers in different languages and cultural contexts in an attempt to engage more thoroughly with their audiences. The current article delves into such features by considering examples of texts written by exponents of the genre. These can be used as models for learners willing to enact their creativity, which can enhance motivation, performance and flair.

Beyond reading

Coined by Espen Aarseth, ‘ergodic literature’ is one which requires nontrivial effort on behalf of the reader. This stands in contrast to ‘nonergodic literature’, where the effort is trivial and consists, for instance, of mere eye movement and page turning. The concept was explored in Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (1997), stemming from the Greek ἔργον (‘work’) with ὁδός (‘path’). It is therefore related to energetic notions such ‘ergonomics’, ‘ergograph’, ‘ergogenic’ and ‘ergodicity’. Such linguistic companions underline the prominence of work in establishing the essence of the genre: the reader is seen as an active rather than a passive participant in the making of the story. Aarseth defied the centrality of medium, placing greater emphasis on function, as the text can be paper-based or electronic but “in a material sense includes the rules for its own use” (Aarseth, 1997: 179). In this context, cybertext – which involves calculations to produce scriptons – is viewed as a subgenre of ergodic literature. Examples include chat bots, where calculations generate textual responses. Another case in point is I Ching, a Chinese divination manual whose 64 symbols or hexagrams can either be produced with 50 yarrow stalks or three coins. This can ultimately prompt the production of more than 4,000 texts.

The reader in the novel

While the concept offers promising avenues for constructivist learning, what do these paths involve? A glimpse of the literature can provide us with examples that can be used as models for learners. A direct way of engaging with the reader in egordic literature is by means of grammar. A case in point is Italo Calvino’s Se una notte d'inverno un viaggiatore or If on a winter's night a traveler (1979), where the author uses the second-person narrative and invites the reader to reflect on the process of reading itself. Every chapter consists of two sections, the first of which narrates the process inherent in reaching the novel’s next chapter. The second one describes the first part of a new book found by the reader. Since its chapters are the first ones of different books, the novel’s protagonists include novelists, translators, governments and even book-fraud conspiracies.

Easier said than done

In this context, engaging readers can involve puzzle solving. Maze, by Christopher Manson (1985), was conceived as a children’s puzzle book and was apparently the world’s most puzzling one ever released at the time. Here, the reader is the guardian of a mansion visited by schoolchildren during a trip and each page is a room in the maze with puzzles to be deciphered. Readers are supposed to find the shortest route to the centre and back, so every page contributes to solving a larger puzzle.

Such endeavours can also occur when the reader is not treated like a character. S. (2013) by Doug Dorst and J. J. Abrams is a story within a story involving a dialogue between two college students Eric and Jen. They seek the identity of Straka, the author of the novel Ship of Theseus. The adventure involves handwritten letters, book excerpts, newspaper clippings, birthday cards, memorabilia, black and white photographs, official documents, a map and even a boarding pass. The authors also include handwritten marginal notes. Such elements contribute to its multilayered narrative, which involves the reading of the novel, the notes made by its translator Caldeira and the students’ marginalia. The latter echoed Abrams’ days at university, where note taking seemed to be commonplace. In an interview for New York Times, the author asked:

“What if, instead of putting it back for someone else to read it, the person who received the book saw those notes and felt compelled to continue the conversation?” (J. J. Abrams and Doug Dorst Collaborate on a Book, ‘S.’ - The New York Times (nytimes.com))

Challenging conventional sequence

Such intricate puzzle solving can involve unconventional sequence as well, as Cain’s Jawbone from the Torquemada Puzzle Book (1934) exemplifies. Written by Edward Powys Mathers, the reader is a detective and has to cut or tear the narrative’s 100 pages. He then has to rearrange them accordingly to uncover six mysteries. This involves countless possible combinations and very few readers have actually succeeded. The author also uses wordplay, hidden clues, several literary allusions and spoonerisms, which occur when the first sounds of two terms are swapped to produce an intended and often funny meaning (E.g. runny babbit instead of bunny rabbit).

Marc Saporta treats the reader to another twist which challenges conventional sequence. Composition No 1 (1961) consists of 150 unbound pages which the reader is supposed to shuffle like a game of cards. An early ‘book in a box’, its pages are devoid of numbers and are printed on one side only, prompting 150 opening paragraphs. As a result, it is up to the reader to connect different fragments on the quest for a linear narrative sequence to tell the story of a mysterious character called X.

Similarly, Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela or Hopscotch (1963) exhibits a strikingly unusual sequence. It tells the story of Argentinian writer Horacio Oliveira living in Paris in the 1950s. He spends his time with a lover called La Maga and a group of intellectuals known as “The Serpent Club” but eventually leaves France to go back to his homeland. The novel, which consists of 155 chapters (99 of which are “expendable”), can be read in two ways: one can either approach it sequentially from the first to the fifty-six chapter or (quite fittingly) hopscotch the whole book following instructions provided by Cortázar. In the latter version, the 55th chapter is left out, leading to a recursive loop where one is left hopscotching between chapters 58 and 131 ad infinitum.

Engaging layouts

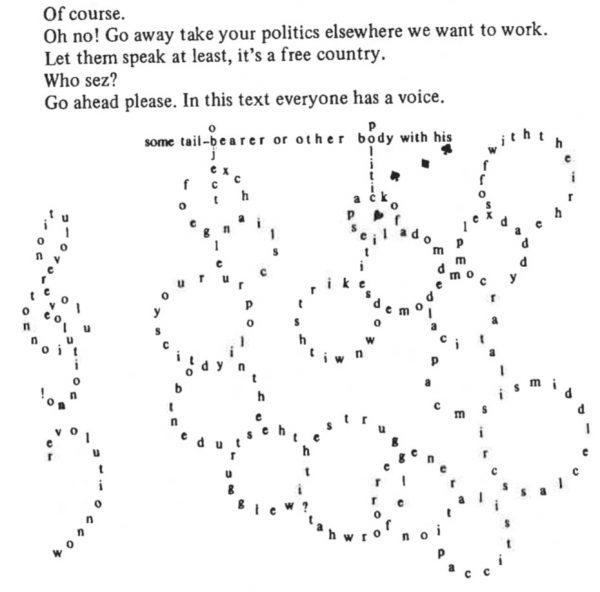

Ergodic literature can also be interactive and stimulating by means of layout, as Thru (1975) by Christine Brooke-Rose vividly shows. The book, related to a seminar on literary theory and shaped by disappearing and recurring narratives by different narrators, involves the use of concrete poetry, mesostics (When vertical phrases intersect lines of horizontal texts), videograms, graphics, spreadsheets and lists. Certain images, such as the ‘caution’ road sign or a rectangle mimicking a car’s rearview mirror, appear repeatedly throughout the novel. The practice of using words to create images provides readers with visual cues which alter conventional layout in line with the author’s musings, as figure 1 illustrates.

Figure 1

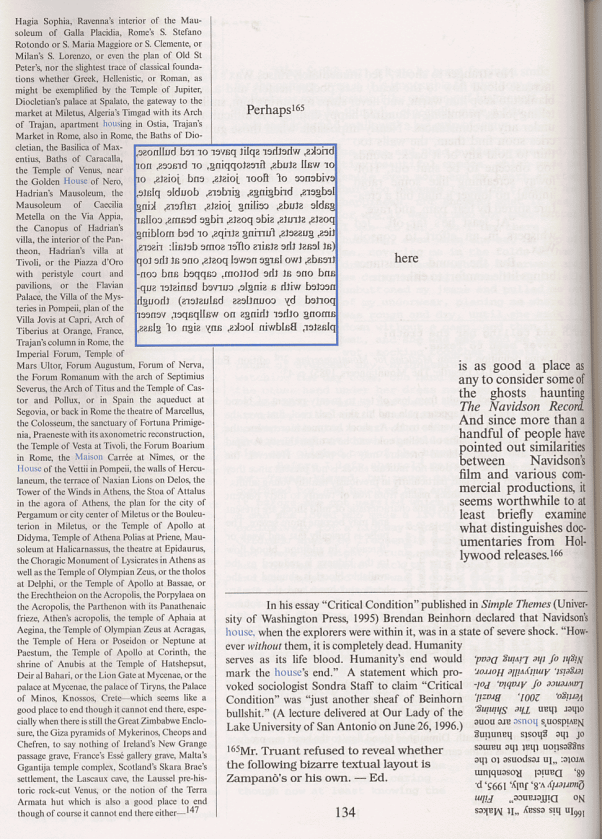

Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000) provides further inspiration for writers seeking to engage with their readers by means of layout. The book – whose multilayered narrative revolves around Johnny Truant’s discovery of Zampanó’s The Navidson Record – must occasionally be rotated to be read (see figure 2) while some pages only have a few words or lines, thereby reflecting the book’s storyline. Other techniques used by the writer include appendices, footnotes, several font colours and typefaces and mirror writing (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Unconventional layout, however, can go beyond the page, as the arrangement of ideas to present a plot can adopt a broader scope. Interaction with readers can also occur by using different formats, as Chris Ware’s Building Stories (2012) visibly exemplifies. The release consists of fourteen printed works packaged in a box set which includes cards, a board game, foldouts, flipbooks, broadsheets and a hardback graphic novel. Such elements are used to tell the story of an unnamed female protagonist from Chicago whose physical disability does not prevent her from becoming a mother. Like books mentioned previously when exploring the unfamiliar sequences offered by ergodic literature, it can be read in any order.

Interacting through form

Interaction with readers can also occur by means of form, whose flexibility can prompt much creativity. For instance, Raymond Queneau’s book in a box titled Cent mille milliards de poèmes or Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (1961) consists of ten sonnets with the same length (fourteen lines) and rhymes. Each page was printed as fourteen strips, meaning that every line can be replaced by another one by the reader, who would turn them accordingly. The interactive nature of the book can prompt millions of poems, leading Aarseth (1997) to dub it a ‘sonnet machine’.

Embracing human rights

Ergodic literature can also serve as a powerful means to voice the struggle of those displaced by the harsh reality of war. Andrea Davis Pinkney’s The Red Pencil (2014) takes readers on a young girl’s journey to a refugee camp in Sudan. Amira’s peaceful village is shattered upon the arrival of the Janjaweed, prompting her to lose what she values until she finds a red pencil which invites her to find comfort in art. This piece of ergodic fiction, based on the Darfur conflict and an ode to the colours of childhood, uses poetry based on testimony and abstract visuals. It serves as a reminder of the potential of literature to engage with readers by raising awareness of human rights.

Conclusion

As shown, ergodic literature uses several elements which language learners can adopt to be more daring when writing. These include grammar, puzzle solving, layout, sequence, form and theme. While such endeavours may be considered far-fetched and incoherent with the constraints of a given syllabus or curriculum, they offer a glimpse of the underlying promise at the heart of the genre: working through its winding paths can be as challenging as it can be alluring.

Questions for readers:

- Which of these strategies would you introduce to your learners?

- Which examples from the literature would you use as models?

- How would your learners benefit from the use of ergodic literature to learn English?

References

Aarseth, E. (1997) Cybertext. Perspectives on ergodic literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Brooke-Rose, C. (1975) Thru. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd.

Calvino, I. (1979) Se una notte d'inverno un viaggiatore. Torino: Einaudi.

Cortázar, J. (1963) Rayuela. Bogotá: Oveja Negra.

Danielewski, M.Z. (2000) House of Leaves: The Remastered Full-Color Edition. New York: Pantheon Books.

Abrams, J.J. and Dorst, D. (2013) S. New York: Hachette Book Group.

Manson, C. (1985) Maze: A Riddle in Words and Pictures. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Mathers, E.P. (1934) The Torquemada Puzzle Book: A Miscellany of Original Crosswords, Acrostics, Anagrams, Verbal Pastimes and Problems, Etc., Etc. & Cain’s Jawbone, a Torquemada Mystery Novel. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Pinkney, A.D. (2014) The red Pencil. New York : Hachette Book Group.

Queneau, R. (1961) Cent Mille Milliards de Poèmes. Paris. Éditions Gallimard.

Saporta, M. (1961) Composition No. 1: A Novel. Paris : Éditions du Seuil.

Ware, C. (2012). Building stories. New York: Pantheon Books.

J. J. Abrams and Doug Dorst Collaborate on a Book, ‘S.’ - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Coming soon! Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Working Through Paths

Daniel Costa, InternationalBeing in Language - The Importance of Stress in all Productive Practice

Peter O’Neill, Ireland