How I became a Storyteller

Jamie Keddie is a Barcelona-based teacher trainer and storyteller. He is the author of 'Images' (Oxford University Press, 2008), 'Bringing online video into the classroom' (Oxford University Press, 2014). 'Videotelling: YouTube Stories for the Classroom' (LessonStream Books, 2017).

Introduction

Some people believe that storytelling is a gift – that some are born with it while others are not. But speaking from experience, I can tell you that nothing could be further from the truth. In these three parts, I would like to share my story of how I learned storytelling.

Part

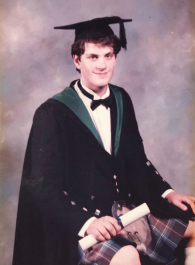

In 1994, after graduating from Aberdeen University with a degree in biochemistry, I decided that science was not my thing. What I wanted from life – above everything else – was to be a musician.

My parents were confused. They tried to persuade me to stick to the original plan and keep music as a hobby. But I had made up my mind and in 1994, I went to study jazz piano at Leeds College of Music in Yorkshire.

It wasn’t easy. I had to support myself by working four nights a week in a bar. And whereas my fellow students were able to supplement their incomes by playing music, that was not an option for me because I was nowhere near the standard required to give public performances.

I came very close to giving up, especially after suffering a humiliating incident in a restaurant. I was with some non-musician friends, and they persuaded me to get up and sit down at a piano in the corner of the room. The only thing I felt confident playing was high-energy boogie-woogie but after a couple of minutes, the waiter came up behind me, closed the piano lid on my fingers and said in front of everyone, “No more, please. I’ll actually pay you if you stop playing!”

But I didn’t give up. I worked hard and eventually, teamed up with a bass player and a drummer. We got a few gigs around the city and from there, things started to develop quite fast.

Me, as a wedding singer, some time around 1998

I built up a healthy repertoire of jazz, blues and pop standards. And when I finished the degree in 1999, I embarked upon my dream career of becoming a cruise ship musician.

A postcard of the Norstar – the ferry I worked on

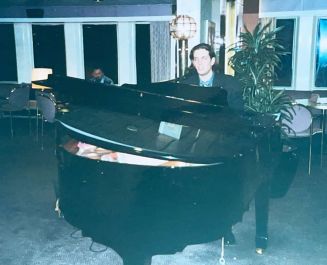

My first job wasn’t particularly glamorous. I played piano and sang on board a ferry that went between the UK and Belgium. One day I would wake up in Hull and the next day, Bruges. Then back to Hull. Then Bruges again. The route was sometimes called the booze cruise as Brits would take it specifically to stock up on cheap continental beer and wine.

This is the only photo I have of me playing on the ferry.

Can you spot my audience? I

wonder if he still thinks about me from time to time.

It was a tough gig. Every night I was required to play five sets, each lasting 45 minutes. But this was exactly where I wanted to be and importantly, I had a Caribbean cruise lined up for later in the year.

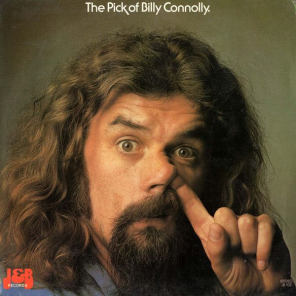

I wonder if you know Billy Connelly, the Scottish storytelling comedian. I’ve always loved the story about how he got into comedy. Connelly initially worked as a welder and played folk music, starting out performing in Glasgow shipyards. During his sets, he would take breaks to engage the audience with jokes and stories. Eventually, those jokes and stories came to dominate his performances, and he went from being a storytelling musician to a comedian who would sometimes play music.

I found this to be quite inspiring and decided that perhaps I could do the same. So, one night on the ferry, after a performance of My Baby Just Cares for Me, I decided to tell a story.

I have absolutely no memory of the story I told, but I do remember the reaction I got. It was an interruption from a drunken passenger who shouted, ‘Ah, shut up and play another song!’

Strangely, I didn’t feel rejected by this. Just a few years before, I had been offered money to stop playing. And now, here was someone who seemed to genuinely appreciate my music. That was the story I told myself, in any case!

From that moment on, I decided that jokes or stories would have no part in my sets – it would be strictly music only.

Part 2

When I was around 14 years old, I secretly wanted to be a comedian. This was the UK in the 1980s, when stand-up comedy had entered an exciting new era.

I was inspired by young, innovative performers like Ben Elton, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, Victoria Wood and, of course, the slightly older Billy Connolly, whose comedy albums regularly got played in our Scottish household.

I had a little notebook where I obsessively wrote down all my joke ideas. But I told no one. Society was much more reserved back then, and I was terrified of the ridicule I might face if people discovered my ambition.

My insecurity ran so deep that when my mum found my notebook one day and innocently asked what it was, I snatched it from her hands, insisted it was private and later destroyed it.

Just like that, my comedy dreams went up in flames.

Any lingering desires I had to be a comedian were finally extinguished 14 years later. While working as a musician on a ferry crossing between Hull and Bruges (see part one here), I attempted to tell my audience a funny story. It was not well received, and I bombed (= failed in comedy terms). From that moment, I realised that my destiny lay elsewhere – with music, I guessed.

I had actually taken my own electric piano onto the ship. This allowed me to practise during the day and learn more songs for the night. Combined with the three hours and 45 minutes of performance required each evening, this turned out to be more than my arms could bear – and the unfortunate result was repetitive strain injury.

It was bad news: the doctor ordered me to leave the ship and give up playing for at least six months. Fortunately, the ferry company was very understanding and allowed me to disembark while the ship was in dock rather than at sea.

(That was a joke.)

This is me leaving the ship.

I don't know why I look so happy.

Perhaps it has something to do

with the crate of Belgian beer

at the bottom of my trolley.

I returned to my parents’ home in Scotland and spent the summer moping around the house and generally feeling sorry for myself. After a few weeks of this, my mum suggested that I go to Barcelona and ‘do one of those TEFL courses’. (Teaching English as a Foreign Language.)

So that’s what I did. And 20 years later, I’m still here.

I didn’t turn my back on the piano – not immediately. But gradually, my passion and focus started to shift from music to teaching.

Now, at this stage, you might be wondering, ‘OK, so how did you learn storytelling?’

Well, I’ve just told you: I became a teacher.

I’ll admit it – there's a bit more to it than that and I'll explain in part III (coming next).

But my question is: Why doesn’t teaching naturally lead to storytelling for every educator? All of the best teachers I had were storytellers. Of all the resources, materials and tools at a teacher’s disposal, stories are the most fundamental, versatile and effective. Storytelling is a core function of language – and yet, in language teaching, it’s often treated as niche.

* * *

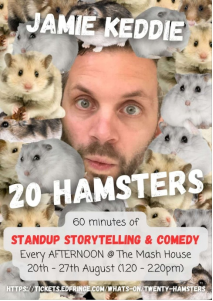

Following the COVID lockdowns of 2020, I decided to try stand-up comedy for the first time. There’s a pretty active scene here in Barcelona, and it wasn’t difficult to get onto a few open mics.

After much hard work, I managed to put together a 60-minute show. And in 2023, I was able to fulfil my 14-year-old dream of performing at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

It was an incredible experience – and one of these days, I’ll tell you what I think teachers could learn from doing stand-up comedy.

This is me leaving the ship.

I don't know why I look so happy.

Perhaps it has something to do

with the crate of Belgian beer

at the bottom of my trolley.

I returned to my parents’ home in Scotland and spent the summer moping around the house and generally feeling sorry for myself. After a few weeks of this, my mum suggested that I go to Barcelona and ‘do one of those TEFL courses’. (Teaching English as a Foreign Language.)

So that’s what I did. And 20 years later, I’m still here.

I didn’t turn my back on the piano – not immediately. But gradually, my passion and focus started to shift from music to teaching.

Now, at this stage, you might be wondering, ‘OK, so how did you learn storytelling?’

Well, I’ve just told you: I became a teacher.

I’ll admit it – there's a bit more to it than that and I'll explain in part III (coming next).

But my question is: Why doesn’t teaching naturally lead to storytelling for every educator? All of the best teachers I had were storytellers. Of all the resources, materials and tools at a teacher’s disposal, stories are the most fundamental, versatile and effective. Storytelling is a core function of language – and yet, in language teaching, it’s often treated as niche

* * *

Following the COVID lockdowns of 2020, I decided to try stand-up comedy for the first time. There’s a pretty active scene here in Barcelona, and it wasn’t difficult to get onto a few open mics.

After much hard work, I managed to put together a 60-minute show. And in 2023, I was able to fulfil my 14-year-old dream of performing at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

It was an incredible experience – and one of these days, I’ll tell you what I think teachers could learn from doing stand-up comedy.

Part 3

In January 2007, I received an email from my mum with a message: 'Please watch this video'. Below the message was a link to a mysterious 15-second video of two panda bears.

About an hour after the email, my mum phoned me on my landline to make sure I had watched the video. She thought it was the funniest thing she had ever seen. This was how we used to do the internet!

Teaching before YouTube…

Some of you might remember the old days when teaching with video meant wheeling a bulky TV set into your classroom and relying on episodes of Mr Bean, Fawlty Towers, Wallace and Gromit or whatever DVDs were on offer.

But in 2005, the world was introduced to YouTube and things would never be the same again.

Online video was exciting, unpredictable and full of possibilities. Virtually anyone could upload anything, and that changed everything – new genres, creative techniques and responsibilities for educators. Videos became shorter, more interactive and sometimes chaotic. We were no longer bound by the familiar schedules and categories of film and TV. On YouTube, you never really knew what you were going to get.

As a newly qualified teacher, I was blown away by the changes. In February 2008, I started a website called TEFLclips – a place for me to explore ideas for using online video and share them with other teachers.

In my very first post, I shared an idea based on my mum's favourite viral video. My suggestion was for a simple video prediction activity that went like this:

- Position the screen so that everyone in the class can see the two pandas. If anyone has seen the video before, make sure they do not spoil the ending.

- Play the first few seconds of the video, then press pause.

- Tell your students that something unexpected happens next. Ask them to guess what it is and get everyone to write their idea on a Post-it note.

- Ask students to stick their Post-it notes on a designated area of the classroom wall.

- Go over their ideas and offer praise and/or corrections where needed.

- Finally, play the full video and see who came closest to predicting the actual outcome.

What happened next?

As I continued exploring online video, I began noticing a change in my teaching habits. Instead of going straight for the play button, I would add a short introduction – a quick explanation about how I had found the video or why it had caught my attention.

Small changes like this seemed to make a difference. Students appreciated the personal touch. They were more curious to see the video and more invested in the activity. With the panda video, for example, it was no longer just a clip of two animals. It was a connection to Jamie’s mum.

Over time, this shift became more deliberate. I began taking a few minutes to offer some context, just as a museum guide might do with an exhibit.

Without realising it, I was starting to think of video not just as content, but as a kind of story with characters, context and connection beyond the screen.

Videotelling

In this previous LessonStream post, I wrote about my father and how many of his stories seemed to originate from the screen. He would regularly tell me and my siblings about funny adverts, TV moments, comedy sketches, film scenes and, more recently, viral videos – an everyday human act that I refer to as videotelling.

Jack Keddie, some time around 2012

Perhaps influenced by this, I began to apply the same technique to the videos I used in the classroom. To give you an example, the panda prediction activity might have started like this:

I want to tell you about a YouTube video I saw recently

It involves two pandas at the zoo: a mother and her baby

The baby is lying on the floor, sleeping

Dreaming about whatever it is that babies dream about

Meanwhile, the mother is taking advantage of this moment of peace

She is sitting in the corner eating a snack

And after a few seconds, something unexpected happens

Can you guess what happens?

Think carefully and write down your ideas on a Post-It note

This approach changed not just how I introduced videos, but how I thought about my role in the classroom. Like a museum guide, I was learning to create connections, build anticipation and offer the human context that made the experience meaningful. Museum guides do not just point at objects – they tell stories, share discoveries and invite us to care.

Over time, videotelling became the hallmark of the lesson ideas I was sharing on TEFLclips – a site that went on to win a British Council ELTons award and eventually evolved into what is now LessonStream.

Me, pre-grey, with Neil Kinnock –

the greatest prime minister we almost had!

Learning storytelling

As I developed this approach, I realised something important: I wasn’t just becoming a better teacher – I was becoming a better storyteller. Each video became a chance to practise the craft: to spark curiosity, ask good questions and respond to students' answers. It wasn’t the technology that made the difference – it was the human connection.

Teacher-led storytelling is not about taking the spotlight. It is about setting the stage. But too often, we hand over our power to the screen. We press play and step back, hoping the video will do the work. We become button-pushers instead of creators of meaningful experiences.

But our role is more than that. We have to keep students engaged and motivated. We have to immerse them in language and give them real reasons to communicate. We have to encourage them to explore ideas and develop fluency.

For me, all of this became possible when I embraced storytelling. That’s my story, anyway.

Your storytelling journey starts here!

Storytelling is at the heart of great teaching. It’s how we connect, make ideas stick and inspire learning.

Some people believe storytelling is something you’re born with. But that’s just not true.

Like playing an instrument, it’s a skill you can learn with the right kind of practice.

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website

How I became a Storyteller

Jamie Keddie, Spain