Humane Intelligence: The Basis of Educator Wellbeing in the Age of AI

Effie Kyrikaki is the founder of NeuroLearningPower® (NLPower), the evidence-based mentoring framework and training methodology that empowers and certifies teachers in their enriched roles as Educational Neurocoaches. As a Master NLP Trainer, coach, and international teacher educator specializing in wellbeing in education, she has supported over 3,000 teachers and their students to flourish. Her work focuses on Wellbeing in Education through Humane Intelligence, inclusion, and the empowerment of teachers as whole beings. She writes for educators seeking to reignite purpose, harmony and wholeness in their personal and professional lives. Email: effie@metamathesis.edu.gr

Introduction: The Birth of Humane Intelligence

The world of education stands at a fascinating crossroads. Artificial Intelligence (AI) can now write lesson plans, assess essays, and even simulate human thinking and empathy. Yet the more advanced technology becomes, the clearer it is that the essence of education is not intelligence alone, it is humane intelligence.

Humane Intelligence (HI) was born from years of observing teachers in classrooms, mentoring conversations, and wellbeing research in schools. As I was observing Chat GPT and other LLM models grow, one pressing question infiltrated my thoughts and research: How do we stay deeply human in an increasingly automated world? The answer was the construct of Humane Intelligence.

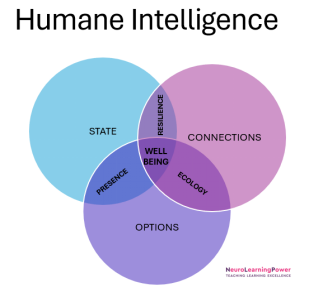

I do not consider Humane Intelligence (HI) to be a competitor to AI. Rather, it is its essential differentiator, the compass that keeps teaching and learning human. Humane Intelligence refers to teachers’ capacity to regulate ourselves, relate to others meaningfully, and respond consciously, even under pressure. These three capacities form the pillars of HI: State, Connections, and Options, as this Venn diagram illustrates.

Figure 1

The Structure of Humane Intelligence

Note. The three interlocking circles illustrate the dynamic system of Humane Intelligence. State, Connections, and Options represent the core capacities supporting holistic educator wellbeing. Their intersections form Resilience (State + Connections), Presence (State + Options), and Ecology (Connections + Options), with Wellbeing at the centre.

Humane Intelligence draws from relational neuroscience, coaching psychology, NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming), and the growing body of research on self-compassion and teacher wellbeing (Brown, 2019; Davidson & McEwen, 2012; Kyrikaki, 2026; Mercer & Gregersen, 2020). It positions wellbeing not as an afterthought, but at the heart of the process as the soil in which learning, resilience, and creativity grow. The wellbeing of teachers thus becomes a prerequisite for the wellbeing of learners.

As Parker Palmer famously wrote, “You teach who you are.” Humane Intelligence begins exactly there - with who we are when we teach.

PILLAR 1. STATE – The Inner Climate of Teaching

Have you ever entered a class only to be welcomed by your learners’ anxious questions: “are you OK today, Miss?” before you even open your mouth to utter a word? Every class begins long before the first “Hello, children.” It begins with the teacher’s state. The teacher’s breathing, tone, pace, and body carry silent messages that shape the emotional weather of the classroom.

In NLP terms, state is the dynamic interplay between the body, the brain, and the environment, the mental and physical conditions one experiences at any given moment, what Stephen Porges (2011) calls the neuroception of safety. It is sometimes conscious and sometimes not. In the previous example, you may have not even realised you were bothered when you had entered the class until your learners pointed your attention to that direction. When teachers are regulated, their nervous systems signal safety to students. When stressed, their physiology transmits threat, through subtle non-verbal cues. In other words, the first coursebook an educator teaches is their own neurology.

Research shows that wellbeing teaching and learning are interdependent (Kyrikaki, 2023). Emotional regulation supports executive functioning, creativity, and empathy (Davidson & McEwen, 2012). For teachers, self-regulation becomes the foundation for effective pedagogy and relational presence. Additionally, we now know that teacher wellbeing has a positive impact on students’ success. Specifically, it influences students’ experiences in the classroom, and their learning outcomes (Duckworth et al., 2009; Braun et al., 2020; Braun, 2021).

Teacher wellbeing, therefore, is not simply the secret sauce in the recipe of learning, it is the recipe itself. Where do we stand globally in this respect? When my first presentations 10 years ago talked about teacher flourishing, I sounded like a joke. Who cares about the emotional state of teachers? Not even teachers themselves. As Rita Pearson said in her famous TED Talk “I have a lesson to teach. I teach it, they learn it, case closed.” Well, the case is only now opening.

Teacher burnout is a global concern. Teachers leave the profession in drones and countries are already facing shortages at alarming rates. If you are a nursery teacher and wish to relocate to New Zealand, the country will pay you an extra 10.000 NZ dollars as relocation benefit. In language teachers social media groups in Greece, the main discussion is alternatives to working as a unappreciated, badly paid teacher who has to work away from home repeatedly in the first years of his/her career. A 2023 study of 786 Greek primary teachers found high levels of chronic stress, sleep difficulties, and unhealthy coping habits (Zagkas et al., 2023). Similar findings echo across Europe and the U.S.: the Eurydice Network (2021) reports emotional exhaustion among European educators as a “systemic risk,” while a RAND (2022) survey found U.S. teachers twice as likely as other professionals to experience frequent stress.

Empowering educators is not simply a matter of retention. It is a matter of inspiring the very heart of education to not only remain in the profession but also beat at the rhythm of humane growth as models for their students. Self-compassion, as Sarah Mercer (2021) argues, is a vital path to that optimal state. It allows teachers to respond to difficulty with kindness rather than self-criticism, maintaining access to the calm, cognitive parts of the brain that enable both good teaching and authentic care. In turn, it models the very emotional literacy we want students to develop.

Humane Intelligence offers a path forward; not by adding tasks, but by deepening awareness of state. Regulation becomes not an indulgence, but a professional responsibility. Action research among student teachers at the University of Athens and Thessaly has revealed a deep need for emotional regulation strategies. As a participant stated at the evaluation of an experiential workshop on how to safeguard their own wellbeing before they enter the classroom: “This is exactly what I needed as a student teacher now and for my future career as an educator.”

Practice Box

Humane Intelligence Practice: The Teacher’s State

Try it yourself before class or a meeting.

Purpose

Self-regulation, optimal state

How it works:

- Stand still, feet on the ground.

- Inhale through the nose for four counts, exhale for six. Repeat 4 times

- Feel your shoulders drop; soften your jaw.

- As you are holding the doorknob, whisper an intention: “I lend calm.”

Notice how your breath changes your physiology and this in turn changes your state- and your presence in that optimal state changes the room.

Humane Intelligence Practice: The Room’s State

Try it with your students at the beginning of class

Purpose

Self-regulation, concentration of attention, optimal learning state

How it works:

- Have students sit, back straight, feet on the floor and guide to start breathing deeply.

- Ask them to touch the thumb and index finger of one hand and rub them together concentrating on the feeling of touch for about 30’’. If a thought comes, just let it go and keep concentrating on touch.

- Now have them touch their palms and let one palm slowly glide along the other palm for 1 min.

- You will notice some students close their eyes, and that’s ok if they wish to.

- With a slow, deep voice tone, guide students to feel around a book or a notebook with their eyes still closed.

- At the end of about 1 more minute ask them to open their eyes and look at the centre of the class (pointing at yourself).

Ask them to notice the quiet in their heads at the end of this sensory regulation activity.

PILLAR 2. CONNECTIONS – The Space Between Us

“Connection,” writes Brené Brown (2019), “is why we are all here.” As social beings, we are wired to connect. Dunbar’s (1998) work on social cognition reminds us that the human brain evolved to manage complex relational networks.

In Humane Intelligence, Connections refer to the interwoven webs of relationship within and beyond the classroom — between teachers and students, among colleagues, peers, and families, and crucially, between the teacher and the self.

Connections cannot be extras to learning; they are the medium through which learning flows. Teachers draw strength not only from inner calm but from relational safety — the support of peers, mentors, and loved ones.

The Impact of Chronic Stress on Connection and Learning

When Maria, a dedicated teacher, noticed herself snapping at students she once understood intuitively, she felt both guilty and numb. She wasn’t uncaring, she was exhausted. Her body had been in fight-or-flight mode for months.

Prolonged stress like Maria’s floods the brain with cortisol, disrupting the prefrontal cortex—the area responsible for empathy, reflection, and emotional regulation - while overactivating the amygdala, the brain’s alarm centre (Arnsten, 2009; McEwen & Morrison, 2013). Over time, this rewiring impairs memory, focus, and relational capacity, often manifesting as compassion fatigue, where emotional depletion replaces genuine connection (Figley, 2002). As cortisol suppresses oxytocin and serotonin, the chemistry of trust and belonging fades (Heinrichs et al., 2009).

In education, such chronic stress doesn’t just drain individuals, but it quietly dismantles the relational and cognitive foundations of learning. Restoring wellbeing, safety, and humane connection is therefore not a luxury but a prerequisite for genuine teaching and learning (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

Relational safety allows students to take risks, to speak, to err, to grow. As Mercer and Gregersen (2020) highlight, emotional safety enables authentic engagement and resilience.

In mentoring work with teachers and counsellors, mentoring itself often becomes a scaffold — a structure of trust and reflection that allows a teacher to grow beyond what they could do alone. Humane mentoring models the same compassionate communication teachers later extend to students: guidance without control, support without judgment.

State + Connections → Relational Resilience

When State meets Connections, we see resilience in relational form, not as personal toughness, but as the ability to stay emotionally connected to oneself and others amid the moment-to-moment demands of teaching, enabling teachers to stay strong through pressure, not despite it. It is the ability to remain open, empathetic, and grounded even when the system demands speed or perfection.

When teachers experience trust and belonging, their nervous systems recover more quickly from stress. This co-regulation fuels the stamina to remain compassionate and present in challenging classrooms (Mansfield et al., 2016). Relational resilience thus becomes the heartbeat of humane wellbeing in the educational ecosystem.

Practice Box

Humane Intelligence Practice: The 10-Minute Idea Exchange

Friday: Ask for one idea

Monday: Try it out

Tuesday: Give thanks and feedback

Purpose

To transform isolated exhaustion into bounded collaboration.

How it works:

On Friday send a Chat / SMS /Email or speak In person

“Hi ___. I’m stuck with ___ (e.g., transitions getting noisy).

Do you have 10 minutes to share one idea that worked for you?

I’ll try it on Monday and let you know how it goes.”

Humane Intelligence features

- It protects energy – 10 minutes only, not an endless conversation.

- It regulates emotion – shifts from “complaining” to “experimenting.”

- It models dignity – a clear request, a clear commitment.

Small details that make a big difference

- Ask for one idea, not “anything you’ve got.”

- Name when you’ll try it (“Monday, first period with class B1”).

- Keep the 10-minute limit, use a timer if necessary.

- Close with a thank-you. Absolutely remember to provide a short update as soon as you try the suggestion. It strengthens the peer-to-peer connection, which solidifies both parties’ relational resilience.

PILLAR 3. OPTIONS – The Freedom to Choose Our Response

“Between stimulus and response there is a space,” wrote Viktor Frankl. “In that space lies our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

The third pillar of Humane Intelligence is Options — expanding the space between impulse and response.

For teachers, options are not only classroom strategies; they are ways of perceiving behaviour, managing energy, and maintaining boundaries. A self-regulated teacher can see possibilities instead of problems, curiosity instead of threat.

Under stress, the brain’s survival systems narrow perception — everything feels urgent or personal. Regulation and reflection reopen access to perspective, allowing teachers to see students not as obstacles, but as young humans seeking connection and meaning.

Options + Connections → Ecology

Where Options meet Connections, Ecology expands. In HI ecology is the awareness that every choice ripples through a relational ecosystem. A teacher’s tone, feedback, or pacing does not act in isolation but within a web of emotional and social consequences. Teachers aware of the ripple effects of their actions create systems of trust and curiosity. They teach choice, not control, modelling the humane intelligence of agency.

A teacher who used to complain about one of her ESL teenage classes had such a moment of epiphany after a NeuroLearningPower training session. With a knowing smile and eyes wide open with surprise, she whispered, “They’re not misbehaving, they’re calling for connection.” That shift in perception transformed her classroom. She stopped fighting behaviour and started guiding growth.

Humane Intelligence is this art of pausing before reacting, of seeing through the eyes of compassion. It is how wellbeing becomes wisdom. Ecological awareness invites us to act with relational ethics — to teach with the understanding that wellbeing is collective.

That’s Humane Intelligence at work: the quiet transformation of the relational field.

Options + State → Presence

At the overlap of Options and State emerges Presence — the capacity to remain grounded and conscious in the moment. Presence allows teachers to pause, breathe, and engage choicefully rather than reactively.

Practice Box

Humane Intelligence Practice: Expanding your Options

Purpose

Learn to reframe challenges as useful information

How it works:

- When faced with a difficult moment, ask: What am I feeling right now? Openly name your emotion.

- What is my internal dialogue? (e.g. "This class is unbearable.")

- What is an unhelpful belief about the situation? (e.g. “Teenage students are always creating trouble.”)

- Change the belief to information: "Their restlessness is information: perhaps the pace of my activities needs better adjustment."

- Repeat daily for a week. Patterns will emerge — and so will freedom.

Humane Intelligence Practice: Relational Options

Do in class on a free speaking slot

Purpose

Idea generation, practice seeing multiple options, focus on solutions instead of problems, critical thinking, asking for help, relational safety

How it works:

- Have students in groups of 4 and give them post-it notes or cards to write on.

- Quickly revise ways to suggest ideas on the board (you could/ an idea can be to/ an option is, etc)

- Ask each student to write very briefly about a situation that concerns them. (e.g., I find it hard to get up in the morning.)

- Place all the cards facing down.

- Students in each group take turns drawing one situation card and reading it aloud.

- As a team, they find at least 3 different options for each situation without judging them as right or wrong.

For each situation, they discuss:

- “Which option helps me stay calm?”

- “Which keeps my connection with others alive (if others are involved)?”

- “Which opens the best path for everyone (if others are involved)? ”

Closing Reflection: The Teacher as Humane Intelligence Model and Compass

The Humane Intelligence framework reminds us that teaching is not about perfect plans, but about presence. It is about being aware enough to regulate ourselves, kind enough to connect, and wise enough to choose consciously. It places wellbeing at the heart of this integration, not as an end goal, but as the meeting point of harmony, inner regulation, connection, and conscious action.

In a world fascinated by artificial intelligence, Humane Intelligence brings us back to the essence of education: humans supporting other humans to grow.

Reflection for the Week

What kind of presence do I bring into my classroom — and what kind of presence do I want to leave behind?

References

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Braun, S. S. (2021). Promoting teacher wellbeing: A review of evidence and policy implications. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1773–1799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09606-4

Braun, S. S., Roeser, R. W., & Mashburn, A. J. (2020). Teacher wellbeing, classroom quality, and student outcomes: A multilevel perspective. Educational Psychology, 40(6), 645–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1705247

Brown, B. (2019). Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. Random House.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3093

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903157232

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6(5), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<178::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-8

Eurydice Network. (2021). Teachers in Europe: Careers, development and wellbeing. European Commission. https://education.ec.europa.eu

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

Heinrichs, M., von Dawans, B., & Domes, G. (2009). Oxytocin, vasopressin, and human social behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 30(4), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.005

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Kyrikaki, E. (2023). Emotional and Professional Support Measures for ESOL Teacher Well-being - Peer Support and Mentoring as Factors of (Women) Educator Flourishing. In J. Miller & B. Otcu-Grillman (Eds.), Mentoring and reflective teachers in ESOL and bilingual education. IGI Global.

Kyrikaki, E. (2026). Humane intelligence and educator wellbeing: A new perspective on professional flourishing. [Manuscript in preparation]. NeuroLearningPower Education Series.

Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidence-informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016

McEwen, B. S., & Morrison, J. H. (2013). The brain on stress: Vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron, 79(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.028

Mercer, S. (2021). Exploring teacher wellbeing: The importance of self-compassion. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 847–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211014937

Mercer, S., & Gregersen, T. (2020). Teacher wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. Jossey-Bass.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

RAND Corporation. (2022). Teachers are not OK, even though we need them to be. RAND Research Report. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-4.html

Zagkas, K., Kyriazis, G., & Kotsis, K. (2023). Occupational stress, burnout, and coping strategies among Greek primary school teachers: A cross-sectional study. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 20(2), 151–169.

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website

Humane Intelligence: The Basis of Educator Wellbeing in the Age of AI

Effie Kyrikaki, Greece