- Home

- Lesson Ideas

- Poetry, Picnics and Plant Pots: A Waldorf Approach to Teaching English in the First School Years

Poetry, Picnics and Plant Pots: A Waldorf Approach to Teaching English in the First School Years

Kavita Desai grew up in England and has been teaching English and French, mainly at German Waldorf schools, for the past 16 years. She currently lives in Freiburg and teaches at the Freie Waldorfschule Freiburg-Wiehre. She is particularly interested in language acquisition and bilingualism in young children.

Introduction: an invitation

“Would you like an olive?”

“No thank you. Would you like a cherry tomato?”

“Yes please! Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Enjoy!”

“May I have a cupcake?”

“Of course!”

“Thank you!”

These were simple little exchanges, but it was a delight to watch my class of eight-year-old English learners skipping about and offering each other food in English during our “English picnic.” The children discovered that they could speak English not only to each other, but also to the parents who had accompanied us on our outing. This brought a new dimension to the experience, since these were people who had not practiced the phrases with us in the classroom beforehand.

Scenes from our “English picnic”

At Waldorf schools children usually learn two new languages from grade one. In most cases one of these is English. English lessons in the first school years include recitation, singing, role play, stories, musical instruments, drawing, games, and movement - and perhaps even gardening and cookery. It is a hands-on approach built on direct experience. Children encounter the richness of the language itself, and connect to the world in which they live through meaningful experiences and the involvement of the senses.

This article is an invitation to join me in my English lessons. We will explore teaching methods and the aims of language teaching in Waldorf schools, which go beyond the obvious goal of language acquisition. Examples will open a window into what this looks like in practice in the first school years, giving the reader a taste of what it feels like to learn and teach in this way. Since an important part of Waldorf education is the teacher’s individual relationship to the subject matter, it must be emphasized that the examples given here, while consciously founded on principles of Waldorf education, also reflect my own personal approach.

Building bridges of empathy and understanding

A particular feature of Waldorf education is the focus on a direct, living experience of the sounds and colours of the new language (Kiersch, 1997). Pupils learn to listen with sensitivity, guess imaginatively and meet the surprises and ambiguities of the other language with openness and curiosity. In this way they build up an artistic relationship to the language as a sensory reality, learning to trust their senses and honing their faculties of perception (Kiersch, 1997). It is the teacher’s task to bring the essence of the language to life for the pupils, to help them feel, for example, how within a two-letter exclamation such as ‘Oh’ an entire universe of cultural experiences can reside (Denjean, 2011). Learning a new language in this way becomes a schooling in empathy and an “education for peace”, not through theoretical discussion but by learning to identify with the feelings and perceptions of others (Kiersch, 1997). The ability to access the world from another’s viewpoint is crucial, not just on the scale of international conflict, but in everyday life in societies which are becoming increasingly multicultural and diverse. How an understanding of other cultures and languages can promote tolerance and interest in otherness can be observed in intercultural Waldorf schools, such as the ‘Freie Interkulturelle Waldorfschule Mannheim’, where more than half of the student body speaks a native language other than German (Brater, Hemmer-Schanze and Schmelzer, 2007).

In this sense the Waldorf approach is more relevant today than ever. In its beginnings over a hundred years ago, Waldorf education brought a dimension to language teaching which can still challenge us to question the goals of modern language instruction today. Rudolf Steiner, the founder of the first Waldorf school in 1919, turned the tables on the widely accepted idea that languages should be learnt so that pupils can serve and function in the existing social order. By contrast, the primary question becomes: What potential do children carry in themselves, and how can this potential be developed (Kiersch, 1997)? By teaching modern languages in a way that supports the children in the development of their own humanity, language teachers can do their part in equipping them not just with language skills, but with an increased social-emotional intelligence. In the following sections, we will look at how Waldorf language teaching seeks to meet these goals.

Teaching as an art

At Waldorf schools language teaching in the first three school years takes place orally, without reading or writing. Through nursery rhymes, songs, poems, stories and games the children bathe in and become familiar with the new language. Lessons are held almost entirely in the target language, with minimal translation. Right from the beginning children are exposed to authentic, high-quality language (Kiersch, 1997). Even Shakespeare may make an appearance!

A central principle is the idea of the teacher as an artist (Kiersch, 1997). The children are placed at the centre of the process and the content supports the children’s development (Masters and Rawson, 1997). Subject matter should be delivered in a way that is relevant to the children’s age, their situation, their group and individual needs. When working with literature, “teaching as an art” means making the writing, in all its genius and subtlety, accessible to the children.

Speaking to the heart

How can this work? A poem I like to speak with third graders is in fact an extract from Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act V, scene 2:

When icicles hang by the wall,

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

When blood is nipp’d and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

To-whoo;

To-whit, to-whoo, a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

There is nearly always a child in the class who can produce a superb owl call in their cupped hands and will be happy to do so. You can even start with the owl’s hoot and the children will have understood something about the poem even before you have started speaking. Icicles can be drawn on the blackboard along with a pail of milk if you don’t have a nice old bucket that could alternately be used to illustrate this line. To show how the blood in our extremities is painfully nipped by the cold we can pinch our fingers. In this first part of the poem, we have several clear roles which can be performed to convey meaning without resorting to translation: Dick the shepherd, blowing on his hands while guarding his sheep, Tom bearing logs into the house – bring in some real logs, nice and heavy, and the children will argue over this role! – and the person carrying the frozen milk home. Hold up a white plate and ask the children, “What is this? A plate? No! It’s frozen milk!” Knock on the “milk” to show its solidity, then put it in a bucket to be carried. Finally we have Joan, scrubbing the greasy pots in the scullery. A child can scrub a real upturned pot (which doesn’t have to be greasy!) at this point in the poem. Roles can be freely mixed between genders!

This poem paints vivid pictures that teach us something of what life was like in England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and at the same time, with their elementary themes, the pictures resonate with children today. The poem also holds a wealth of alliteration. When we speak the line “When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl” in the second verse, we hear those crabs roasting and hissing. It does not matter that pupils will not understand every word of such a text. It is important to realise that language has a conceptual and an emotional component, and that while adults often focus on the former, children are more sensitive to the latter, to how language makes them feel (Wutte, 2020). For learning to occur, children need to associate feelings with what they are learning (Kiersch, 1997). Texts, as works of language and thought, should certainly be understood, but above all they should find a place in the children’s hearts (Kiersch, 1997).

Another poem I like to introduce right at the beginning of primary school is the first part of “Someone came knocking” by Walter de la Mare:

Someone came knocking

At my wee, small door;

Someone came knocking,

I’m sure — sure — sure;

I listened, I opened,

I looked to left and right,

But nought there was a-stirring

In the still, dark night.

This poem can be easily acted out using the classroom door. It can evolve naturally into a kind of game, where the child outside doing the knocking is allowed to run and hide around the corner, so indeed no one can be seen when we open the door.

It is often a challenge to create moments of quiet anticipation in a lesson. With this poem it is relatively easy to get the class to enter into the spirit of the game and wait silently until they hear the child outside knocking. What makes this activity interesting is the invisible connection to the classmate outside and the unpredictability of just how things will go this time. Some children wait a good while outside the classroom before knocking – silence! How long the class will wait at this point without speaking is often surprising. Some children knock very, very quietly, so that we really have to strain our ears. Many variations are possible. How about whispering the poem? Or whispering just certain lines? Once again, we are working with feelings, setting a mood, playing with the language by speaking at different speeds and volumes. The children are engaged on an emotional level, and this helps them to build an individual relationship to the language.

The power of artistic expression

The examples above show how the teacher, guiding the children in speaking the text and taking on roles, acts as a medium for the language in the first school years. The more the teacher can embody the language, can be the language, the easier it is for the children to absorb the language and make it their own. When we share a poem, a song or a rhyme with the children we need to have formed our own artistic relationship to what we are speaking, so that the words are “alive” when they arrive in the children’s ears.

Bearing this in mind, storytelling has enormous potential. Supported by gestures and pictures, interactive performative storytelling can bring whole worlds to life in the classroom. In addition to language acquisition, storytelling supports children’s development on many other levels (Wutte, 2020). Singing, drawing, acting and reciting are all forms of artistic expression, and as such can help children to trust in their own creativity and build up resilience (Eckart, 2020). In the light of the challenges facing children in today’s and tomorrow’s world, which can easily lead to feelings of resignation and helplessness, strengthening confidence and building up resilience is important for all children.

Discovering the world

A central part of equipping children for life’s challenges is ensuring that they gain a meaningful understanding of the world. A genuine connection to the world is a resource that can be called upon throughout life (Clouder and Rawson, 1998). Waldorf teaching methods, which work towards building life skills apply as much to modern language teaching as to any other part of the curriculum. Everything should be practical in nature so that the children, especially in the first school years, learn out of direct experiences, by first doing and then understanding (Masters and Rawson, 1997). Content should be delivered through pictures and lively descriptions rather than defined in abstract concepts (Masters and Rawson, 1997). In our teaching we move from the whole to the parts (Masters and Rawson, 1997). This does not mean that poems or stories cannot be built up over lessons. In this case “the whole” refers to working with authentic, intact language containing meaningful themes for the children. Words are learnt in context, arising out of the stories, poems, rhymes and songs which the children hear, speak and sing in lessons (Masters and Rawson, 1997). In a similar way, grammar rules can later be extracted from the language that has been lived and absorbed in the first school years. Pupils are guided to discover and formulate the rules for themselves (Kiersch, 1997). It is a wonderful moment when six graders discover and really feel the elegance of the present progressive, realising that whereas in German we need to add a word like “now” to express an action taking place at the present moment, in English there is a tense that does the job all by itself.

Engaging the senses

Waldorf education aims to address the overall development of the individual, and is sometimes referred to as an education for “the hand, the head and the heart”. In order to perceive anything at all, we rely on our senses, and sensory perception can be said to be a prerequisite for any kind of human development (Auer, 2007). Perceiving something can be understood as the first stage of the learning process, followed by relating to what has been perceived (Masters and Rawson, 1997). It follows that engaging the senses supports learning in general.

Rudolf Steiner described twelve distinct senses (Soesman, 1995) which were not universally recognised during Steiner’s lifetime. Today however, some of these senses are more widely acknowledged. Take, for example, Steiner’s sense of language which has been examined further in a modern context (Lutzker, 2017) and his sense of movement, now better known under the term ‘proprioception.’ Differences in sensory integration skills impact children’s ability to learn, since the capacity to regulate emotion and attention crucially depends on the level of sensory integration (Bundy and Lane, 2020). When we are aware of pupils’ individual needs, we can support their learning on a sensory level. This sounds complex but can be simple in practice, as shown in the following example:

A classroom play in grade two involved three children taking on the roles of bees:

“We are the busy, buzzy bees

That make honey and wax

From the flowers and the trees…”

All actors were given lumps of bees’ wax. Bees’ wax smells wonderful and becomes soft and warm when held and kneaded. Some children loved to hold it in their hands even when they were no longer speaking their lines. One boy in particular was able to become much calmer and more attentive in this way.

There are many ways of engaging the senses. Movement, including balancing, hopping, skipping, jumping and rhythmic clapping games, is a big part of language lessons in the first school years. I like to bring nature materials such as branches, leaves, moss and stones into the classroom. At Halloween, I close the blinds when we light our pumpkin lantern. When we act out a market scene I bring in real food (not every lesson!) for the children to “buy” and eat. When I sing “I’m a little teapot” with grade one, we drink fruit tea from a big tea pot, and the children guess the flavour by smell and taste, learning words for fruits and berries in the process. Lesson activities take place in English, but when they also broaden the children’s understanding of the world they are meaningful in their own right.

Life skills

It is widely agreed upon that skills preparing young people for life in a globalised world should be actively taught across all subjects. But how can we purposely teach creativity, tolerance or ecoliteracy in a way that moves these ideas beyond desirable concepts into attractive core values to live by? And how can we accomplish this goal in our English lessons? A dual-strand approach in which global skills and language competencies are taught simultaneously, has gained popularity in recent years (Babic, Platzer, Gruber and Mercer, 2022). Waldorf language teaching in the first school years is an example of such an integrated method. The way we teach the language is interwoven with the more fundamental goals of developing sensitivity and respect for others, building resilience through creativity and forming a genuine connection to the world. These are skills for life.

Bringing it all together – an example

The following section aims at integrating all previously described methods in practice.

Jack and the Beanstalk is a great story for grade three. In the classroom, we tell the story in a series of short scenes which are then repeated from lesson to lesson, each time taking the story a step further. At first, I demonstrate the gestures and speak the lines for the children to repeat. It is important that the wording is always the same. After a while the children start to speak without my help and may also find their own gestures. Each lesson, different children take on the roles. Abilities vary and some children will always need me to speak along quietly. This does not interrupt the flow of the story and is hardly noticed by the other children. Weaker English speakers are equally motivated to join in, and it is an opportunity to differentiate according to pupils’ abilities whilst still having a group experience.

Class: Once upon a time there was a poor boy called Jack. He lived with his mother in a little house with holes in the roof.

Jack: Mother, I am so hungry!

Mother: Poor boy, we have no more food, and the cow gives no more milk. You must go to market and sell the cow.

Jack: Very well.

Class: And off he went to market to sell the cow.

In the next scene Jack meets an old woman who offers him five magic beans for the cow. In scene three Jack returns home feeling very pleased with himself, but his mother is furious. “Silly boy!” she shouts and throws the beans out of the window. I provide real kidney beans (or similar) which the child playing Jack’s mother can throw out of the classroom window. The children later hunt for the beans at break time, taking the story beyond the English lesson. In scene four, Jack wakes up to find that over night the bean plants have grown right to the sky. He starts to climb up on one of the bean stalks, higher and higher, and arrives in another country.

The next lesson takes place outside. Pupils bring in plant pots and we all plant magic beans. I supply the soil and a few pots for the children who have forgotten to bring one along, and of course the magic beans (which are in fact runner beans from the garden centre and can grow to a height of 3 metres or more). To give the beans a good chance, I plan this story for May or June. Over the next weeks, as the story unfolds, we experience the magic of the beans sprouting and growing on the classroom windowsill. They grow so quickly that the children see a real difference from lesson to lesson and express excitement and wonder. One boy measured his bean plant meticulously with his ruler at the beginning of each English lesson, until the plant got too long for the ruler. At some point, of course, the children take the bean plants home and plant them in their gardens or in a bigger pot on a balcony or patio.

After the bean planting, before the story continues with a series of scenes acted out in English, I slip in an interlude in German, the children’s native language, so that important background is understood and the story can proceed in English. I tell them that in the sky, a beautiful lady in a shining dress appears to Jack and explains to him that his father, who died before Jack’s birth, was a kind and courageous knight who was slain in battle by a giant. The giant took all Jack’s father’s wealth and made Jack’s mother promise that she would never say a word of this to her son, otherwise the giant would return and kill him. So Jack grew up in poverty. However, he has now found his way to the giant’s country and all the giant’s wealth is rightfully his - if he can be daring enough to win it back.

In the next three scenes Jack first steals the giant’s money, then the giant’s little hen that can lay golden eggs, and lastly the silver harp that can sing with a human voice. Minimal props that leave a lot to the imagination help to bring the scenes to life. A pair of very large snow boots make the giant easily recognisable. The money is in a yellow drawstring bag filled with clinky coins. The little hen is made out of a sock stuffed with sheep’s wool, with a beak and comb of red felt and an opening out of which a wooden darning egg wrapped in gold foil can be squeezed when the giant commands: “Lay little hen!” The silver harp is made of cardboard wrapped in silver foil. When the giant commands: “Sing, silver harp!” the children sing a song such as the Skye Boat Song which they know from previous lessons.

Parallel to acting out these scenes, I like to invent side plots. Once Jack has stolen the giant’s money, he goes to market wearing his old, torn clothes still looking like a poor boy. The stall keepers are not interested and don’t want to serve him until he pulls out one gold coin after another. The children become involved, suggesting things that he should buy. It is up to the students whether he buys delicious food, new clothes or several new cows. Once he brought home roses for his mother. Suggestions that he buy a Mercedes or a play station can be met with humor and a reminder that the story takes place a long time ago when cars or video game consoles did not yet exist – or indeed by adding a time machine to the story and bringing Jack into today’s world for a lesson or two.

The story ends with the giant chasing Jack from his castle (around the classroom) and down the beanstalk (a jump down from a desk). Jack calls to his mother for an axe and chops down the beanstalk. The giant falls down (from the desk). In the final scene, Jack lives happily with his mother, no longer in a little house with holes in the roof but in a palace.

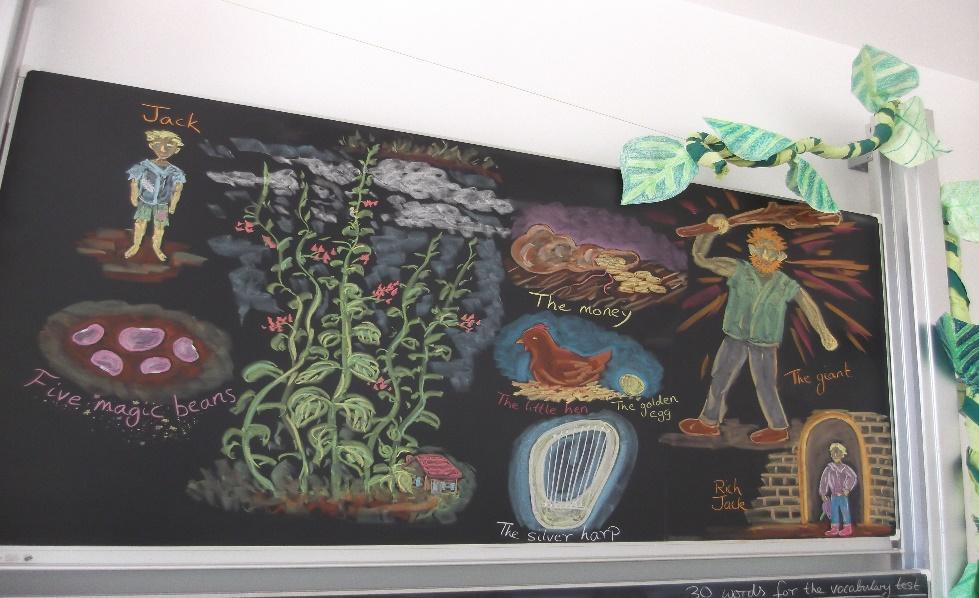

As the story progresses, I draw pictures on the blackboard while the children draw in their English books. Drawing together is another way of sharing a creative experience and forming an emotional connection to the story. In my experience, the children often draw ‘in English’, referring to items in their pictures with the English words and even repeating parts of the dialogue.

Pictures from Jack and the Beanstalk

The children continue to give me reports of their bean plants’ progress, even after the story has ended. After the summer holidays, a few children inevitably return in triumph with a handful of new magic beans.

Children today: “I can make things happen in English!”

In Waldorf language teaching during the first school years, the teacher is by necessity a focal point. The children are often able to speak a lot of English in lessons, but little English in other situations. This was long seen as unproblematic during the first three school years, with recognition that from grade four onwards a different approach is required (Kiersch, 1997).

However, in recent years, many English teachers at Waldorf schools have called for a closer look at what children need in these first school years. Waldorf education is not a closed system, but an evolving approach to education which, like any good system, aims to achieve and maintain high standards through evaluation and adjustment. Moreover, Waldorf education takes the view that different generations of children bring different qualities and needs with them.

I experience today’s children as wanting to be recognised as co-creators, as agents who have an effect on the world. They will let themselves be led in language lessons when we are willing to integrate their ideas. They are delighted when we give them a voice and let them use it, in a general sense and specifically in relation to the new language. When students realize that if they say something in English, it will make something happen, they experience their own efficacy and the immediate power of language as a tool for change.

This brings us back to the “English picnic”. The idea came from the children and arose out of the story “The very hungry caterpillar” which took the form of an interactive puppet show in the classroom. While we told the story, the caterpillar (made out of green beanbags sewn together) crawled through holes in the paper food which the children had made themselves and held upright on their desks. The children decided they wanted to eat delicious food in the lesson too. I suggested a picnic and over the next lessons we planned what we could bring, with pictures on the blackboard. We played “I spy with my little eye” so that the children soon became confident naming all the different foods (and incidentally the colours too). Expressions we would need were practiced with the whole group in the form of call and response and in snippets of role play. We agreed that food should be bite size, so that we could taste everything if we wanted to, without getting a tummy ache like the very hungry caterpillar.

When we finally went on our outing and put the picnic into action, it was magical to experience how an idea materialised into something as concrete as tasty food. The children were particularly connected to the event since they had initiated the activity and been involved in the planning. And asking for a cookie in English and receiving one as a result is a very tangible way for an eight-year-old to experience the power of language!

Conclusion: between individuality and community

Waldorf language teaching focuses on cultivating empathy and understanding, which are essential for functioning communities and cross-cultural understanding. A tendency towards a heightened individuality among young children challenges us to adapt and complement existing methods, for example by balancing our activities and making more space for the children’s initiative. Reciting and singing as a group creates an important foundation, while classroom games and projects can be included to provide more opportunities for individual speaking and interaction between the children. The art of teaching lies in finding an equilibrium between teacher-led and child-led activity.

References

Auer, W.M. (2007). Sinnes-Welten. Kösel-Verlag.

Babic S., Platzer K., Gruber J., Mercer S. (2022). Positive Language Education. Humanising Language Teaching. https://www.hltmag.co.uk/oct22/positive-language-education (accessed December 2022).

Brater M., Hemmer-Schanze C., Schmelzer A. (2007). Schule ist Bunt. Verlag Freies Geistesleben.

Bundy, A.C., Lane, S.J. (2020). Sensory Integration, Theory and Practice. F.A. Davis Company.

Clouder, C., Rawson, M. (1998). Waldorf Education. Floris Books.

Denjean, A. (2011). Die Technick des Übens im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Pädagogische Forschungsstelle beim Bund der Freien Waldorfschulen.

Eckart, R. (2020). Kunst als Brücke zum Leben. stART international e.V. (ed.) Kinder stärken – Zukunft gestalten. Verlag Freies Geistesleben, pp.31-34.

Kiersch, J. (1997). Language Teaching in Waldorf Schools. Steiner Schools Fellowship Publications.

Lutzker, P. (2017). Der Sprachsinn: Sprachwahrnehmung als Sinnesvorgang (n. Edition, Ed.). Verlag Freies Geistesleben.

Masters, B., Rawson, M., (1997). Towards Creative Teaching. Steiner Schools Fellowship Publications.

Soesman, A. (1995). Die Zwölf Sinne. Verlag Freies Geistesleben.

Wutte, Lisbeth (2020). Wieder stark und mutig sein. stART international e.V. (ed.), Kinder stärken – Zukunft gestalten. Verlag Freies Geistesleben, pp.162-173.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Teaching Foreign Languages at Primary School Age

Christoph Jaffke, GermanyPoetry, Picnics and Plant Pots: A Waldorf Approach to Teaching English in the First School Years

Kavita Desai, England, UKWorking with The Civil Rights Movement in the US in Grade 10 (16-year-olds)

Mario Radisic, GermanyWorking with Postcolonial Literature as a Learning Opportunity for the Development of the Young Person

Martyn Rawson, Scotland, UK, Germany