- Home

- Various Articles - Working with Indigenous Languages

- The Politics of Language Learning in New Zealand

The Politics of Language Learning in New Zealand

E ngā iwi, tēnā koutou katoa.

He uri nō Ngāti Hine ahau.

Ko Motatau te maunga

Ko Taumarere te awa

Ko Ngatokimatawhaoroa te waka

Ko Otiria te marae

Ko Tūmatauenga te whare tupuna

Nō Peowhairangi ahau

Ko Paraone te whānau.

Charlotte Goddard is currently working as a Māori language specialist at Waikato Waldorf School and is the across-schools leader for culturally responsive work for Waldorf schools in Aotearoa.

Email: tekahuiwhetu1@gmail.com

Neil Boland is a former Waldorf teacher and works in the School of Education at Auckland University of Technology. Born and brought up in England, he first moved to New Zealand in the 1980s. Email: neil.boland@aut.ac.nz

Abstract

This article considers the importance in schools of teaching and learning te reo Māori, the Indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand. It explores the vital role language plays in working to deconstruct colonial binaries of Māori–Pākehā in Aotearoa and their attendant, unequal power structures, allowing contemporary New Zealanders to explore spaces between these fixed identities and understand better different ways of viewing and experiencing the world.

We are co-writing this article to examine language learning within Waldorf schools in Aotearoa New Zealand, specifically the teaching of the Indigenous language of the country, te reo Māori. This is not a conventional piece on language learning but one which explores language as central in philosophical, epistemological and political discourses, where the social dimensions of language learning are arguably of greater weight than linguistic fluency. It engages with questions of the normalisation of minority languages, persistent colonial legacies, and the position of Indigenous languages in countries which have been ‘settled’ by Europeans [settler countries are usually understood as those in which the colonising population greatly outnumber the original inhabitants, such as the CANZUS countries (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States), as opposed to colonised countries in which the colonisers imposed their rule but remained a minority, for instance, India or Kenya].

After initial context, the article gives extracts from a conversation between us in December 2022, followed by a brief discussion. The dialogue has been lightly edited for length and understanding. A glossary of Māori terms is given at the end of this article. Te reo Māori text is treated as normal text because, as one of the official languages of Aotearoa, Māori is normal. It is not differentiated from English typographically. New Zealand English uses Māori terms frequently as reflected in this article.

A little history

Māori came to Aotearoa sometime around 1300 and were the first people to live here. They spread throughout the islands, establishing the Māori language and culture. Europeans first set foot on the land in 1769, with the European population expanding rapidly from the 1820s onwards. Missionaries were the first colonisers, followed by ever-increasing numbers of settlers. In 1840, many Māori chiefs signed a treaty with the British Crown, Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The Treaty promised to protect Māori culture and to enable Māori to continue to live in Aotearoa as Māori. At the same time, the Treaty gave the British Crown the right to govern New Zealand and to represent the interests of all New Zealanders. The terms of the Treaty remain contested and settlements of Treaty claims for land taken by the colonisers have been heard by the Waitangi Tribunal since the 1970s. Whatever the intent at the time, the status of te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and te ao Māori [Māori language, customs and worldview] declined steadily until the Māori revival of the 1970s.

In many countries, learning additional languages is a question of being able to communicate with people in other countries or learning a ‘useful’ language to increase one’s future earning power. In New Zealand there are additional, or different, considerations. Over the last 200 years, the place of te reo Māori and te ao Māori has lessened as the English language and a Western worldview has dominated. This is not just a question of communication. As in other colonised countries, understanding and speaking English was seen as a way forward for Māori, the colonists’ world was more ‘advanced’, ‘modern’ and desirable. This “reach of imperialism into our heads” (Smith, 2001, p. 21) furthered the hierarchical division of the country. The Native Schools Act of 1867 saw the establishment of Māori schools, separate from schools for European children. One of the priorities of the ‘native’ schools was that all teaching was in English; in later years, speaking Māori at school became a punishable act. Beyond the 3Rs [reading, writing and arithmetic], the curriculum concentrated on domestic and practical subjects. The Act stayed in effect until 1969 [for further information see Calman, 2012].

To give a present-day snapshot, te reo Māori became an official language in 1987. Total immersion preschools for children from birth to school entrance age (kohanga reo) and bilingual and total immersion schools (kura) were established in the 1980s and are now found throughout the country. 17% of the New Zealand population identifies as Māori. Although English is overwhelmingly the language of everyday communication, 20% of Māori can speak te reo Māori and its use in everyday communication increases steadily. Māori words and concepts are used increasingly in New Zealand English (as in this article). The language is not compulsory in schools, unlike for instance Welsh or Irish in their respective countries and has been taught in Steiner schools since the 1980s. Nonetheless, te reo Māori is classed as a taonga (treasure) in Aotearoa and is the most commonly spoken language after English. The next most common community languages are Samoan, Northern Chinese (including Mandarin), and Hindi (StatsNZ Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2018). Te reo Māori can never be referred to as a foreign language as it is the original language of the country. If anything, it is English which is the foreign tongue.

Traditionally, European languages were learned in New Zealand schools, although these have been joined and to some degree supplanted by Japanese, Chinese, Spanish and others which reflect our geographical position as a Pacific Rim country. Teaching and promoting Māori encounters familiar questions of language hierarchies, which languages are considered ‘important’, which often is in part an economic decision. We think it is fair to say that Indigenous languages are not taught in schools in most settled countries.

Conversation

NB: Why is it important for you that te reo Māori is taught in New Zealand Steiner schools?

CG: It’s about building a connection with the Māori culture. If you don't have a connection, if you don't understand the culture, then how are you going to understand learning the language? The majority of languages have a defined structure: there are ways in which sentences should be structured grammatically. The Māori language sometimes follows that path, but other times, the language deviates from this and follows a different track altogether. It becomes more of a language which could be classed as a form of poetry. Understanding the culture out of which the language comes is then essential to understanding how the language works.

If we go to the culture first and begin to look at the beliefs of the culture, how people lived, how people grew up, and then look at how Māori culture has changed through time, a connection is built which creates a spark that ignites interest in the language in learners. If you are learning about someone's culture, you don't realise that you are learning language at the same time.

A lot of Māori teachers use standard resources – workbooks, resources which explain how we use verbs and nouns and all those types of things. They are frequently based on repetition. Short chapters can be set on what you could say at a chemists’ or at a hospital, playground, at home, or at school, learning simple phrases and establishing basic sentence structures.

Then there are resources like rakau, also known as Cuisenaire rods. It is a way to teach the language through the senses. Te Ataarangi (2013) is an organisation in Aotearoa which uses these rods to create pictures and talk to them. The idea is that, in a rūmaki setting (total immersion), you hear through your eyes and you look with your ears. It is also a way to learn Māori customs and values. Their website gives details.

Others, including me, concentrate on pronunciation, learning how to place Māori sounds in your mouth. Aside from the advantage of this for learning the language, it is invaluable on an everyday level as there are so many Māori loan words in New Zealand English – and it is important for Māori that these are pronounced correctly. The same with place names. While Auckland is still called Auckland, it is increasingly known by its pre-European name of Tāmaki Makaurau, the same with Christchurch / Ōtautahi. Much greater emphasis is placed on the correct pronunciation of other place names such as Kaikōura and Taupō which are no longer anglicised. It is a completely phonetic language, so once you know what syllables there are and how to say them, you can write and pronounce any Māori word you like.

NB: Can you talk about the importance of children learning te reo in a country which has been colonised and learning a language that at one point was banned?

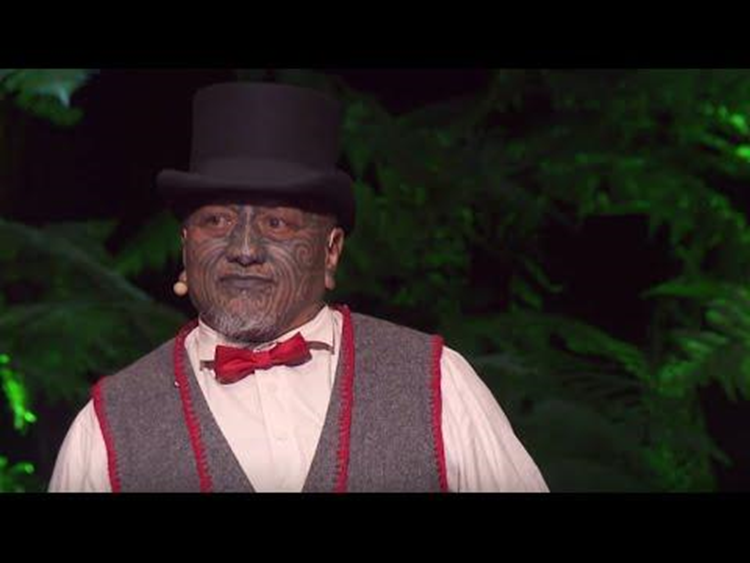

CG: An essential concept in Māori culture is mana. I like how Tame Iti talks about mana in his Ted talk (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qeK3SkxrZRI&t=86s): “Everyone has some form of mana. A part of it is knowing who you are, where you come from and your connection to your land. Mana grounds you; mana makes you solid; mana binds you to your past, present and future.”

(Iti, 2016)

Māori suffered a loss of mana over generations when our language, culture, and knowledge was not seen as of the same value as Pākehā language, culture and knowledge. Overcoming this loss of mana is profoundly important for Māori. Learning te reo Māori, other people learning te reo Māori, using tikanga, acknowledging the importance and value of te ao Māori in Aotearoa is important for us to overcome the past and, with it, decades of inferiorisation and suffering.

Learning and using our language is an important means of overcoming the past. Te reo Māori being used more widely in Aotearoa (e.g. in news broadcasts which increasingly incorporate the language) helps dismantle stereotypes. Māori who were not brought up speaking te reo experience a degree of whakamā – many from this group are learning it as adults, reconnecting with their roots. Reclaiming their culture. This does not happen without some pushback of course. Some Pākehā regularly complain whenever a newsreader says kia ora.

It is important that children who identify as Māori experience that their language has value. They can otherwise feel like they are not being seen in the classroom. They don't know why, they can't explain it, but they can feel like they are not visible. [It was out of this need for children to be ‘seen’ in their own classrooms that Gloria Ladson-Billings developed culturally responsive pedagogy in 1995.] They can't explain it because their parents can't explain it.

Dealing with the past is difficult. It’s also a generational thing, I think. Because of the experiences that my grandfather had, not being allowed to speak his own language in the native schools, having to go into the army, his generation has experienced a lot of hurt. That's why my grandfather didn’t talk about the wars; he didn't talk about his challenges or the hurt he experienced in his past to his mokopuna. It is hard to open up because, for my grandfather’s generation, the past is painful. They carry these hurts which become part of their DNA. We have to decolonise knowledge, so that this generation can have the strength to talk about their experiences. Our grandparents fought really, really hard to start kohanga reo. It has been extremely hard to teach the language where you have conflict, and where in [non-Māori] communities people think that the Māori language shouldn't be taught, that it is not going to get your anywhere, because English is the official language of the country, though of course Māori is too.

When I was younger, it was very much thought that the Māori language is only for Māori, that English should be the language of instruction. Foreign languages should be taught also because that was the way of the future. This has changed. Now we know that we can't survive if we don't have everyone learning the language. For me, personally, I think if you have a connection to Māori culture and you want to learn the language, you are very welcome to learn my language, because you can pass it on to your descendants. Then they can understand better what has happened in our history, and the world will be better for it.

I can't tell you how many times I've been stereotyped for what I wear. You know, going into a supermarket in gumboots after a school camp with a few children and hearing ‘There goes another dole bludger, look at all her kids.’ But this is me. This is how I walk in the world. I used to look at the world with rose-tinted glasses. I thought that everyone was good and kind. I was brought up in a small, rural community and te reo Māori was my first language. I knew what it was like for me to grow up in that situation, and then realise, hey, actually, everyone was growing up in that type of situation. In that community, people should be more respectful towards each other.

It is essentially about recognising each other as human beings. It feels like we have moved on. We want to be equal.

NB: In schools in Aotearoa, including in Steiner Schools, learning the Indigenous language is accepted; it has become more or less expected. What would you say to Indigenous groups in other so-called settled countries like Australia, or Canada, or the US where in the schools by and large they don't learn their Indigenous languages?

CG: I feel really mamae for them, I feel really sad. We need to realise that those that have colonised us, they have to step up. We don’t live in those times anymore. I think it's a big power struggle, if you like, because Pākehā have always been used to being superior. And when you bring in an Indigenous culture, and factor that in, [Pākehā] still need to remain superior at each level. So, the more we go up, they need to go up further.

NB: How is it being a Māori language teacher in schools?

CG: I'm an across-schools teacher. I visit schools which don’t have anyone with a good knowledge of the language. They know that they have to use the language in their teaching, but they don’t have the concepts.

For me, it's not primarily about learning the language, it's about understanding the culture. And if you can understand the culture, you can move forward by learning the language. Teachers think, ‘How am I going to do this?’ Our workload is so full it's not funny, and then to be told that you have to learn and then teach a language at the same time is too much.

Putting the emphasis on learning the culture, rather than becoming technically proficient in the language, is different to what schools overseas might do. It isn’t about passing exams; the priority here is different.

I still remember being at school as Māori. I was fluent in te reo Māori, it was my first language. But to put it to paper, to pass an exam as a first language speaker, I was struggling. Everyone in my bilingual unit had to get trained, repetitively trained, to understand the Pākehā way of thinking, of giving information towards a qualification. This happened when I was away from home, disconnected from my family. I was in another region where you had to wear shoes while walking down the footpath. A very different experience.

By building a connection, creating a spark, an interest, we can move forward, be open to the experience. And if you are closed off and you have a padlock on your heart, then you’re never going to absorb the world and have that human experience.

As a (te reo Māori) teacher, you have to be really resilient. You’ll constantly hear ‘I can’t’ or ‘It’s not for me’ from your students. Despite those negative sentences, we have to keep on going and be supportive, with ‘You can do this!’ or ‘Just follow me, let’s go’. Over time, doing this changes perspectives, which is what we hope for.

The importance of Māori concepts in contemporary Aotearoa

As well as an ever-increasing number of Māori loan words in New Zealand English, Māori concepts play a growing role in describing societal functions and processes in Aotearoa. Among these is kaitiakitanga or guardianship. This concept illustrates the marked difference between Māori and European approaches to the environment, if it is seen as something to be looked after and to be passed on healthy and intact to future generations, or something to extract profit from. Basing governmental environmental policy on kaitiakitanga is an important feature of New Zealand’s response to the climate crisis.

Aotearoa’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic also drew heavily on Māori concepts. It was summed up by the proverb or whakataukī – He waka eke noa | we are all in this together. The then Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, spoke regularly, almost daily, of the importance of whakawhanaungatanga, building relationships, looking after each other. Kia kaha (stay strong) became many people’s email footer. This same phrase was taken up by Queen Elizabeth II who closed her rare address to the New Zealand people during the pandemic in Māori with the words “Kia kaha, kia māia, kia manawanui.”

In these ways, language can be used to help move past and overcome difficult history. It can also aid the building of relationships and connection to help counter present day stereotypes and intolerance. It is usual for students to learn world languages (e.g. English, French, Spanish) for their commercial potential, for study, for advantages which accrue to the individual. However, it is possible to flip the coin and view this differently.

It is not necessary to teach or learn a language from an Indigenous group; it could also be a minority or community language of those from colonised spaces. For instance, learning Arabic in France, Urdu or Bangla in the UK, Turkish in Germany. These languages are, we believe, rarely taught to or spoken by those outside these minority, often marginalised, communities. What kind of gesture would it be for these languages to be taught and learnt, not to pass exams or for self-advantage, but to better understand and communicate with your fellow citizens?

Conclusion

We hope that in this short article we have illustrated some aspects of teaching and learning te reo Māori in Aotearoa. Bringing the language into schools helps make te reo something which belongs to everyone, no matter what their whakapapa. When you go to a big rugby match in New Zealand, the national anthem is always sung twice. The first time is in English and seems to serve as a warm-up for the second time, in Māori. This is when everyone in the stadium, no matter what their background, really opens their lungs.

Language plays a vital role in working to deconstruct colonial binaries of Māori–Pākehā in Aotearoa and their attendant, unequal power structures. It allows contemporary New Zealanders to explore spaces between these fixed identities and understand different ways of viewing and experiencing the world. It encourages everyone to engage with each other to potentially create the kind of cooperative relationship which was hoped for in 1840 by Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Tōku Reo, tōku ohooho — My language, my awakening

Tōku Reo, tōku Māpihi Maurea — My language, my cherished possession

Tōku Reo, tōku Whakakai Mārihi — My language, my precious adornment

Waiho i te toipoto, kaua i te toiroa

Let us keep close together, not wide apart

Nō reira e te iwi,

Tēnā koutou,

Tēnā koutou,

Tēna koutou katoa.

To all, greetings to you once, twice and to all once again.

[This whakataukī speaks to the importance of keeping connected, of maintaining relationships and dialogue so that we can keep moving forward together. It could be used when sharing information about community events or projects that bring people together.]

Glossary

|

Ao Māori, te |

The Māori worldview |

|

Aotearoa |

The contemporary Māori name for the islands of New Zealand (meaning Land of the Long White Cloud). It is becoming increasingly common when speaking English to refer to the country as Aotearoa or Aotearoa New Zealand. |

|

E ngā iwi, tēnā koutou katoa |

Greetings to all tribes |

|

He waka eke noa |

We’re all in this together (lit. we are all in the same waka / boat) |

|

Kaitiakitanga |

Guardianship |

|

Kia kaha, kia māia, kia manawanui |

Be strong, be brave, be patient |

|

Kia ora |

Hello |

|

Kohanga reo |

Total immersion early childhood setting (lit. nest of language) |

|

Kura kaupapa Māori |

Total immersion school |

|

Mana |

Binding, authoritative, valid |

|

Mamae |

Pain, hurt |

|

Mokupuna |

Grandchildren |

|

Pākehā |

European, non-Māori |

|

Te Ataarangi / Rakau |

Cuisenaire rods |

|

Reo Māori, te |

The Māori language |

|

Rūmaki |

Total immersion |

|

Taonga |

Treasure |

|

Tikanga Māori |

Māori custom |

|

Tiriti o Waitangi, te |

The Treaty of Waitangi |

|

Whakamā |

Shame |

|

Whakapapa |

Genealogy |

|

Whakataukī |

Proverb / saying |

|

Whakawhanaungatanga |

The building and maintenance of relationships |

References

Calman, R. (2012, June 20). Māori education – mātauranga. Te ara. The encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-education-matauranga

Iti, T. (2016). Mana: The power in knowing who you are [YouTube Video]. TEDxAuckland. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qeK3SkxrZRI&t=86s

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Smith, L. T. (2001). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. University of Otago Press.

StatsNZ Tatauranga Aotearoa. (2018). Language. https://www.stats.govt.nz/topics/language

Te Ataarangi. (2013). Te Ataarangi [YouTube Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UBmi1r7blM

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

The Politics of Language Learning in New Zealand

Charlotte Goddard, New Zealand;Neil Boland, New Zealand