Applied Peace Linguistics: Some Pioneers and their Contributions

After studying linguistics and education, Jocelyn Wright began working in the Department of English Language and Literature at Mokpo National University in South Korea. Currently, she is exploring applications of peace studies to the context of language teaching, learning, and research. Email: jocelynmnu@yahoo.com

Introduction

Being you, you have multiple identities and wear many hats. As language learners, how often do you reflect critically on your psycho-social purposes for learning? As language users, how often do you consider the impact of your expression and its role in promoting harmony and justice? As language teachers, how often do you teach with the intention of reducing conflict and violence or building peace? As language researchers, how often do you carefully examine learning, use, and teaching from a peace perspective? If rarely, what has prevented you from doing so? Perhaps, you feel quite busy with and possibly burdened by your normal workload and daily routine? Or maybe you have simply never heard of the field of (applied) peace linguistics (PL)?

If the former case resonates with you, first and foremost, I want to empathize with you. Language learning requires continuous effort, using languages necessitates confidence and competence, teaching is a worthwhile but demanding profession, and research comes with its own set of challenges. If you have never heard of PL, you are not alone. I myself only became aware of the field recently, although its academic roots extend as far back as the 1987 Linguapax Conference at least!

So, are you curious as I have been to learn more about this interdisciplinary field? Biography can be an entry point, and I have been able to identify and get in touch with several individuals around the world who self-identify as peace linguists (Figure 1) and have contributed explicitly in various ways to PL. By introducing these inspirational and dedicated human beings and their work, I hope to give you an idea of the diversity of experiences and orientations of each as well as a general sense of how the field is slowly developing in interesting and promising directions. Moreover, I hope to present avenues for you to continue your learning about important concepts, useful pedagogies, practical activities, and more with plentiful resources. Ready for a brief chronological presentation?

Figure 1. Diverse faces of peace linguistics

Francisco

First of all, you may be interested to learn that many people consider a founding father of PL to be a Brazilian scholar named Francisco Gomes de Matos. This visionary peace linguist, whose colorful career spans over 60 years, and who was recently recognized as a Teacher of Peace by PAX Christi USA, became an English teacher in 1956 and a linguist in 1960 after graduating with a Master’s in Linguistics from the University of Michigan. He completed his Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics at Pontifícia Universidade Católica in São Paulo in 1973. In his dissertation on linguistic principles and in his early work, he argued for the humanisation of language teaching and learning. Though he sometimes claims his commitment to PL started in the 1990s when he coined the concept-term of ‘communicative peace’, essentially referring to constructive and dignifying communication, he had previously begun advocating for human and linguistic rights and responsibilities as well as peace as a universal priority in language education.

Francisco is a prolific writer of academic and creative works. Some that he highlights include his Portuguese book Comunicar para o bem: Rumo à paz comunicativa [Communicating for good: Towards communicative peace] (2002), a chapter about PL entitled ‘Language, peace and conflict resolution’ in the Handbook of conflict resolution edited by Morton Deutsch and Peter Coleman (2006) and an article more focused on language education ‘Peace linguistics for language teachers’ (2014). However, he also recommends a poster he created on ‘The goals of peace linguistics’ in Rhymed reflections: A forest of ideas, ideals and ordeals (2018), a collection in his unique style. Throughout his work, he demonstrates a humble commitment to humanising language teaching and PL, and advocates on behalf of peaceful communication, and the pursuit of nonkilling, nonviolence, and peace. One particular strength of Francisco’s is his creative and imaginative approach to PL and language teaching. Some of his signature ‘createchniques’/‘crea(c)tivities’ include having students produce posters (Figure 2), checklists, pleas, poems, puzzles, and other word play involving translating, translanguaging, and transmediation. Proposing questions as prompts for praxis, Francisco (2014) asks how one can:

- express their communicative dignity in speaking, writing, or signing?

- nurture compassion communicatively?

- convey communicative harmony during classroom interactions and in on line communication?

- improve mutual understanding, bilingually or multilingually?

- cultivate communicative serenity (through uses of prose or poetry)?

- prevents [sic] acts of communicative aggression?

- improve their communicative humility by apologizing when being unfair to someone?

- use languages to improve intra and intergroup communicative harmony?

- help peace initiatives, movements, projects (of a local, national, regional, or international scope)?

- imagine and establish a Peaceful Language Users` Club in [their] school or community?

- humanize their critical/questioning competence in a discussion?

- encourage peaceful uses of languages through artistic productions?

- contribute to strengthening uses of languages on the Internet for international cooperation and solidarity?

- use languages peacefully as communicative-life-improving forces?

- educate themselves and others (in their family, for instance) to learn to use languages peacefully for the good of all living beings? (pp. 420-421)

Normally, after such a list, Francisco would ask if you could think of other questions to add.

Figure 2. Posters by Gomes de Matos from www.estudenaaba.com

David

While he declined to take credit for pioneering the field, world-renown British linguist David Crystal, supported the movement towards peace by publishing the first formal definition of PL in A dictionary of language (1999) and A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (2003), respectively. His definition is:

A climate of opinion which emerged during the 1990s among many linguists and language teachers, in which linguistic principles, methods, findings, and applications were seen as a means of promoting peace and human rights at a global level. The approach emphasizes the value of linguistic diversity and multilingualism, both internationally and intranationally, and asserts the need to foster language attitudes which respect the dignity of individual speakers and speech communities. (1999, pp. 254-255)

You can probably agree that such an approach would be relevant to contemporary language teaching and learning as well as varied situations and contexts of use.

Patricia

The next pioneer is another Brazilian scholar, Patricia Friedrich. Patricia received her Ph.D. in English linguistics from Purdue University in 2001, but her educational background includes the study of both languages and literatures. In her writing, she has covered a wide range of critical topics. Those interested in learning especially about ‘peace sociolinguistics’ may be pleased to know that she has published a book called Language, negotiation and peace: The use of English in conflict resolution (2007) and Applied linguistics in the real world (2019) with a chapter entitled ‘Working on peace, diplomacy, and negotiation’ and edited volumes, notably Nonkilling linguistics: Toward practical applications (2012) for the Center for Global Nonkilling and English for diplomatic purposes (2016). She is currently editing a book on anti-racism and linguistics and Englishes online. Very much in line with her mission of peacebuilding, she is drawn to projects that further understandings of justice and inclusiveness, peaceful communication, and cultural awareness. Quite suitably, she teaches courses in sociolinguistics, forensic linguistics, and the history of English. Among other notable achievements, Patricia has facilitated the creation of such degrees as Disability Studies and Conflict Resolution at New College and chairs the New College Anti-Racism Council in her unit.

You may find sociolinguistic insights from Patricia’s different works which often combine theoretical, empirical, and practical elements critically enlightening as have I. Whatever your context, the following questions from her 2019 text may also stimulate reflection:

- If two otherwise identical university courses were offered to students with similar profiles, where one class is taught regularly and the other is overtly instructed to use more peaceful communications, would outcomes assessment turn out different for each class?

- What would the attitude of English learners be to the instruction of a curriculum of peace linguistics to the general offering of their program?

- What would a discourse analysis of essays of First Year Composition students, overtly taught about peace and language, reveal?

- Would a group of business people be able to identify and change, where appropriate, elements of their boardroom negotiations after being instructed about peace linguistics? What would their attitude about those changes be?

- What would the feedback of future diplomatic workers be if they were overtly taught about peace linguistics in an effort to facilitate their future interactions in the field?

- What would a discourse and content analysis of ESL/EFL/world Englishes/English as an International Language instructional materials reveal with regards to their peace-fostering potential?

- What would an inventory of peace-enhancing and conflict-fostering content in different media (movies, TV series, recent bestseller books) reveal and how could the result influence our next steps in peace linguistics and peace education?

- What could a survey of academics reveal regarding their openness to attitudes toward peace linguistics education (and peace education in general) at the university level? (pp. 127-128)

Rebecca

While the American Professor Emerita and distinguished scholar-teacher Rebecca L. Oxford, famous for her award-winning work on language learning strategies, has not used the exact term PL much in her publications, she has contributed in noteworthy ways with her interdisciplinary and multimethods ‘language of peace approach’. Rebecca’s educational background (with degrees in Russian language and educational psychology from prestigious universities), her distinguished career, and life experiences have enabled her to publish 15 volumes, of which seven are on peacebuilding, transformative education, and spirituality. Three that particularly stand out are The language of peace: Communicating to create harmony (2013), an edited volume, Understanding peace cultures (2014), and a recent co-edited text Peacebuilding in language education: Innovations in theory and practice (Oxford, Olivero, Harrison, & Gregersen, 2021). At the moment, she also co-edits two book series: Spirituality, Religion, and Education and Transforming Education for the Future, and she will soon publish another practical peace book for language teachers: Teaching languages for global expertise: Peace and positivity across cultures. If you would like to read about diverse perspectives on the concepts of peace and peacebuilding, example research projects, or multimodal activities for integrating peace into the classroom, you may wish to turn to her works for inspiration.

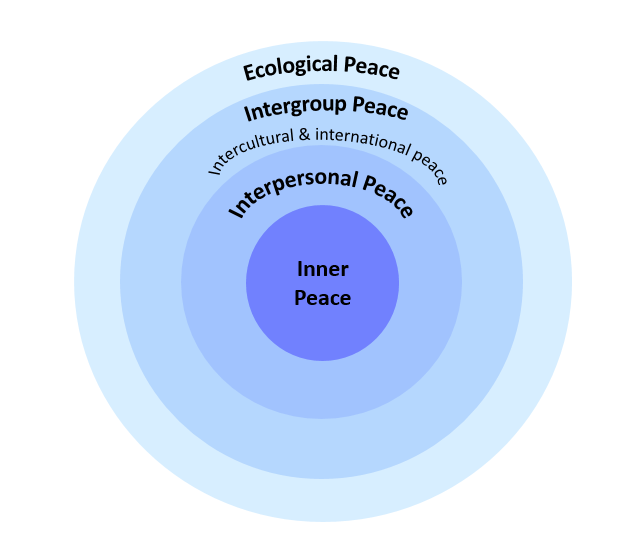

One especially important contribution to PL is her multidimensional framework (Figure 3), which has proven productive as an organizational structure for later projects. This can be useful for incorporating ‘peace consciousness’ into our lives and practice. Below, I purposefully leave you with a sampling of occasionally liberally modified peace language activity titles from Oxford (2017) to stimulate your curiosity and imagination: Peace Mural Collaboratively, Fight Bad Feelings Through Counterevidence (or Visualisation), Use Paradoxical Intention, Do Situation Analyses, Use Positive Self-Talk, Use the SMILES Approach, Learn and Mirror Neurons, Communicate with Nature, etc.

Figure 3. Oxford’s (2013) multidimensional peace framework (adapted)

Frans

Another academic, who has worked on the connection between peace education and Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) for almost a decade, is Frans Kruger. Frans is currently a senior lecturer in educational philosophy and theory at the University of the Free State in South Africa and serves on the editorial board of In Factis Pax, an online peer-reviewed journal of peace education and social justice, and as associate editor of Education as Change. In his research, Frans has explored the connection between critical peace education and TESOL by drawing on Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s immanent materialism and how this has been taken up in Multiple Literacies Theory. The title of his 2015 doctoral dissertation, which he completed at the University of Pretoria, is Mapping peace and violence in the TESOL classroom. Through this project, Frans explored how adult language learners transformed themselves corporeally and incorporeally through the process of becoming literate. Frans has also published research related to critical peace education, social and ecojustice education, and critical posthumanism.

In his 2012 article, he emphasized the social responsibility of TESOL professionals as communications specialists being “at the forefront of promoting peaceful interaction” (p. 17) as “models of peaceful interaction” (p. 20) while acknowledging that they were actually playing only “a peripheral role in educating for peace” (p. 17). After presenting concepts, summarizing previous research, he offers ideas for critically integrating peace education into local communicative language teaching and content-based courses for teaching peace, including themes to incorporate into language curriculum (from affective aspects, multicultural understanding, and human rights to conflict resolution, global issues and social imagination), principles of peace education (such as democratizing the classroom and practicing linguistic non-violence), and humanistic and communicative methods to use (discussions, role-plays, collaborative problem-solving tasks, games, brainstorming, and projects) to develop both communicative competence and communicative peace. He also argues that “TESOL training programmes at universities should all include courses on peace theory, conflict resolution and peace education [and that t]hese topics should be addressed from a critical perspective” (p. 25). Provocatively in later work (e.g. 2015), Frans emphasizes the plurality of peace literacies and argues that we cannot teach peace, but must invent it. Those keen on post-structural philosophy may appreciate his different perspective.

Noriko

A pragmatician over in Japan, Noriko Ishihara, has been working on PL since about 2016. In an email, this Professor of Applied Linguistics and (T)EFL at Hosei University described her work as follows, “I facilitate language teachers' professional development courses in Japan, online, and elsewhere with a special focus on second language (L2) pragmatics and intercultural communication. I am working to bridge peace linguistics and critical awareness of equity and diversity in language learning/teaching”.

The practical new second edition of Noriko’s book Teaching and learning pragmatics: Where language and culture meet (2022), with Andrew Cohen, includes PL with examples of how it could be applied in language learning/teaching. This research-informed book on systematic pragmatic instruction is very useful for anyone interested in PL, given the importance of situated and contextualized language use. It emphasizes and illustrates principled and reflective teaching and aspects of communication that are often neglected in L2 textbooks (e.g. listenership, gendered language) which play a role in empowering language users to manage conflicting relations and build and maintain more peaceful ones in multilingual and multicultural interactions. In chapter 2, she identifies the components of teacher knowledge required for L2 pragmatics instruction: knowledge of a range of pragmatic norms in the L2, of pragmatic variation, metapragamatic awareness, of how to teach L2 pragmatics, of how to assess pragmatic competence, of learners’ identities, cultures, proficiency, and other characteristics, of the (pragmatics-focused) curriculum, and of the role of L2 pragmatics in educational contexts (p. 21). Since these may not have been taught in many teacher education programs or language classrooms, they may mention here may motivate further professional development, personal learning, or inquiry.

Andy

Andy Curtis, an applied linguist living in Canada who served as the 50th President of TESOL International, is accredited with designing and teaching the first credit-bearing PL course for undergraduates at Brigham Young University–Hawaii in 2017. (This interdisciplinary course is still being offered.) He was also the guest editor for the landmark 2018 TESL Reporter Special Issue entitled ‘From peace language to peace linguistics’. Since 2017, he has published around a dozen articles on PL, and he has recently been researching and writing about what he dubs the New Peace Linguistics (NPL). In an email, he stated that NPL “has a much more explicitly political focus, on those with the power to bring about peace or to start wars. For example, analysing the language of leaders like Trump and their followers.” Andy’s book called The new peace linguistics and the role of language in conflict is due out in 2022.

Andy’s efforts to flash a light on PL in the past few years has made the field more visible. If you are interested in setting up a PL course at the college or university level, his co-authored article, ‘Peace linguistics in the classroom’ (Curtis & Tarawhiti, 2018) may offer useful considerations as well as insights for doing so. In initiation, the stated learning objectives were that successful students would complete the course being able to:

- demonstrate an in-depth understanding of the fundamentals of communicating for peaceful purposes, using written and spoken language

- explore, examine and articulate the cultural and linguistic aspects of the languages of conflict and of peace

- gather, analyze and present data on people's perceptions of peace, in relation to language and culture

- present/perform and explain an original, creative work — poetry, song, painting, dance, etc. — reflecting what they have learned on the course

- carry out a critical discourse analysis of a text which shows how language can be used to create peace or to create conflict. (p. 83)

Usman

In Nigeria, Usman Muhammed Bello teaches in the Department of English at the University of Abuja. According to him, he has contributed to the development of PL through his application of pragmatic and grammatical frameworks. As he states, regarding a 2020 publication: “My article, ‘Minimising conflicts and confrontations in language use: Perspectives from peace linguistics’, blends these two frameworks in the theorization of a non-confrontational approach to matters of disagreement.” We congratulate Usman on recently completing his Ph.D. dissertation, entitled The lexico-syntactics of peace linguistics: A linguistic analysis of selected international land and maritime boundary agreements (2021). Usman has joined only a handful of others who have also published PL-explicit theses or dissertations.

Like Andy, he is interested in textual analysis, but rather than focus on the discourse of leaders, he prefers to examine the language in diverse texts surrounding conflict-related issues. Those who read his work may gain ideas about how to go about this as well as awareness about different language choices in authentic texts and their effects.

Sandra

On the other side of the globe is a Colombian peacebuilder, applied linguist Sandra Liliana Rojas-Molina. Sandra completed her undergraduate studies in philology and languages with an emphasis on English and did an M.Sc. in Amazonian Studies at Universidad Nacional of Colombia. She also holds an M.Sc. in Applied Linguistics from Barcelona University. Currently, she is working as a professor at Institución Universitaria Colombo Americana in Bogotá, where she has taught subjects like linguistics, language and society, and pedagogy. Sandra has carried out research on sheltered instruction observation protocol, sociolinguistics (Colombian indigenous languages in contact) and PL.

A major PL project of hers to date is the extensive working report she published in 2019 entitled ‘Peace linguistics in the language classroom: A document analysis research’. This paper, which offers a broad overview, compiles concepts, theoretical foundations, and concrete pedagogical actions from PL literature as well as few examples of recent empirical research. It may be helpful to those starting out in the field and lead to further exploration.

Jocelyn

And where do I fit into all this? A newcomer to the field, based in South Korea, I first heard about PL in 2018 when I was studying and learning to practice nonviolent communication (NVC) and happened upon some of Francisco’s work. I became fascinated with his life journey and wrote a biographical piece about him for Humanising Language Teaching in 2019 entitled ‘Peace linguistics: Contributions of peacelinguactivist Francisco Gomes de Matos’. More recently (2021), I published a book review in In Factis Pax on Peacebuilding in language education by Oxford et. al in which I included a typology of PL and a poem on its evolution. I expect to publish more PL pieces soon and hope my involvement in linguistics, reflective practice, social justice education, and other areas of value to language teaching will guide me well.

On a practical note, I have been experimenting with incorporating NVC and peace-related topics, materials, and skills into classes and my local curriculum, and I am currently quite excited to be transforming some of my skills-based courses into English for Peacebuilding Purposes (EPP) ones. For my upcoming writing classes, I plan to integrate brainstorming and expressive writing combining poetry and journaling in one section and more dialogic writing activities and storytelling in writing circles in the second with scaffolded peer feedback as we explore peace-related themes and issues and experiment with processes informed by some of the previously-mentioned references.

Conclusion

The connections between PL and your life and work may now be more obvious to you, but in case you are still asking yourself ‘So what?’, let me summarize. As language users, learners, teachers, or researchers interested in peace and peacebuilding in your own contexts, you can systematically analyse texts, discourses, and interactions, your own and others. In language teaching, you can choose to focus more on transformative language-related objectives or educational ones. For example, you could help students develop awareness of and use of communicative peace or the language of peace through practical language activities. You could focus on cultivating peace-promoting interactions and relationships in your classrooms through meaningful, holistic, and collaborative pedagogical practices and advocacy. More focused on peace education, you could choose, adapt, or develop curriculum, contents, and materials related to the topic of peace. As learners, you could also request these! Through such efforts, you may model, develop, teach/invent, or research peace-promoting awareness, understanding, attitudes, and behaviours.

In this brief article, I presented only 10 short biographies of peace linguists. Numerous others are contributing to PL although they may not yet be using the term or may only recently have started to do so! If you are one of those, you may be glad to know that I launched a Facebook group to connect scholars and practitioners around the world who are interested in discussing, researching, and reporting on PL and peace language education. I welcome you to join our growing group by visiting this link (https://www.facebook.com/groups/peacelinguistics) or getting in touch with me! Together, we can work towards “the goal of promoting peace and peacebuilding through systematic study, deliberate teaching, and conscious use of languages spoken, written, and signed” (Wright, 2021) in our classes, schools, and communities!

Selected references

/Very many references have been listed above. Below, I list only those mentioned in citations/

Crystal. D. (1999). A dictionary of language (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Curtis, A., & Tarawhiti, N. (2018). Peace linguistics in the classroom. TESL Reporter, 51(2), 77-95.

Friedrich, P. (2019). Applied linguistics in the real world. New York: Routledge.

Gomes de Matos, F. (2014). Peace linguistics for language teachers. DELTA, 30(2), 415-424.

Ishihara, N. (2022). Teaching and learning pragmatics: Where language and culture meet (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Kruger, F. (2012). The role of TESOL in educating for peace. Journal of Peace Education, 9(1), 17-30.

Oxford, R. L. (2013). The language of peace: Communicating to create harmony. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Oxford, R. (2017). Peace through understanding: Peace activities as innovations in language teacher education. In T. S. Gregersen, & P. D. MacIntyre (Eds.), Innovative practices in language teacher education: Spanning the spectrum from intra- to inter-personal professional development (pp. 125-163). Cham: Springer.

Wright, J. (2021, July 6). ELT Concept #12: Communicative peace and (applied) peace linguistics. Willy's ELT Corner. https://willyrenandya.com/elt-concept-12-applied-peace-linguistics/?fbclid=IwAR2_k9MpgHhoKh9ovnHD3Wrxabzap8MaxPcxhhCT8nFdZfvv-_UAJoB7gGI

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

101 EFL Activities for Teaching University Students – Book Preview

Hall Houston, TaiwanApplied Peace Linguistics: Some Pioneers and their Contributions

compiled and edited by Jocelyn Wright, South KoreaThe Socratic Method: A Practitioner’s Handbook

reviewed by Brian Welter