- Home

- Various Articles - Primary

- English in Public Primary School in Venezuela, Experiences 2018-2019: A Case Study

English in Public Primary School in Venezuela, Experiences 2018-2019: A Case Study

Juana Sagaray is the Project Manager at the British Council, Venezuela. She was a teacher trainer for 25 years. She has been a researcher and a materials designer. She holds a PhD in Education with a speciality in the teaching of English. Email: juana.sagaray@britishcouncil.org.ve

Maria Teresa Fernandez is a teacher trainer and monitoring and evaluation of learning (M&EL) researcher. As an ELT-Consultant Associate she has worked in different design and M&EL projects. She holds a PhD in Education with a speciality in the teaching of English.

Email: mariateresaf@elt-consultants.com

Wendy Arnold is the co-founder of ELT Consultants, founded in 2009, with 55 global Associate consultants. She has 30 years’ experience in ELT as a primary teacher, trainer, materials writer, and Consultant. Her special interest is early literacy and learning language through projectwork. She has published on both these interests. She holds an MA in Teaching English to Young Learners (5 to 17 years).

Email: wendy@elt-consultants.com Website: https://www.elt-consultants.com/

Introduction

Background

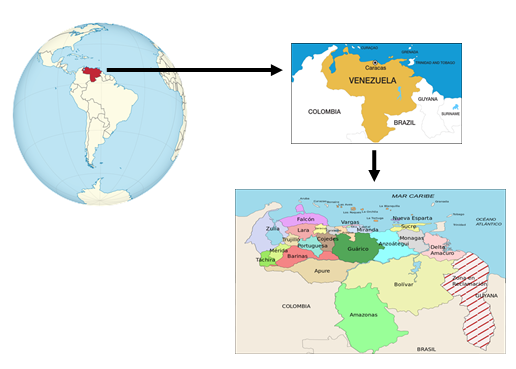

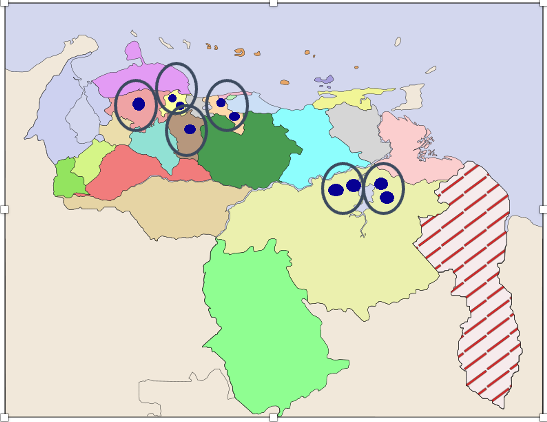

Venezuela is the most urbanised of all the Latin American Countries. Most of the population live in the urban areas in the north of the country (93%). There are 24 States, including the capital district in Caracas. Refer to figure 1.

Figure 1: Latin America, Venezuela, 24 States including the capital district

The main language in Venezuela is Spanish but there are 30 indigenous languages in addition to immigrant languages which include: Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian and Portuguese. English is mainly spoken by professionals, academics, and businesses such as the oil industry, and tourism.

The teaching of English in Venezuela is mandatory in the public Secondary schools, and despite it being in the 2007 Venezuelan National Curriculum for Primary education it is rarely done because there are not enough trained speciality English teachers.

In 2013, The British Council together with Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador (UPEL) collaborated with ELT Consultants who trained 60 UPEL teacher trainers to design 10 modules of a new teacher training programme. As there was a lack of trained speciality English teachers it was decided that generalist class teachers in the public schools could be trained with some English language proficiency and appropriate methodology for delivering language lessons. The teachers were approximately Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) A0/A1 and the training was delivered extensively over a year. The programme was called ‘Diploma in English Language Teaching from Primary school teachers’ or DiPELT. The innovations for this project were:

- the primary teachers were generalist trained, that is they were trained to deliver all the national curriculum subjects

- the primary teachers had no/little English language proficiency

- the primary teachers did not have experience in the appropriate methodology to deliver a foreign language, but they were already experienced teachers who knew their students

- each module of the teacher training programme was divided into 3 workshops. Each workshop had two components: a) language proficiency, and b) continued professional development (CPD) to exemplify the methodology needed to deliver language classes. The CPD component was sequenced with the trainer modelling a teaching technique in workshop 1, micro-teaching of the demo technique in workshop 2 and reflection in workshop 3. Workshop 3 also included designing an ‘action plan’ for incorporating the teaching technique in a lesson. See Table 1 below for a breakdown of the module content.

Table 1: Breakdown of module content

|

MODULE |

||

|

Workshop 1 |

Workshop 2 |

Workshop 3 |

|

Language proficiency |

Language proficiency |

Language proficiency |

|

CPD – Trainer demo |

CPD – micro-teaching |

CPD – reflection and planning ‘action plan’ |

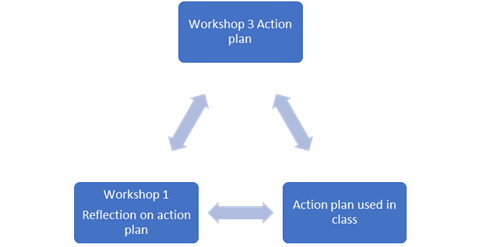

Reflection on how the ‘action plan’ worked is built into the next module workshop 1 CPD. So, there is continual looping of teaching methodology being modelled, micro-teaching, putting into an action plan (which develops into a lesson plan) and reflection. See Figure 2 below to show the looping of demo lesson into practice.

Figure 2: Looping cycle of action plan planning, used in class, reflection in following module workshop 1

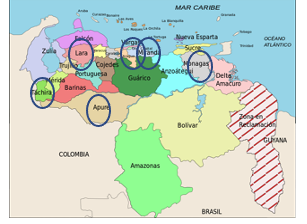

The 60 teacher trainers worked in pairs and delivered training to teachers in 6 States around the country. Over 900 generalist teachers were trained. Refer to Figure 2 for UPEL teacher training colleges.

Figure 3: UPEL teacher training colleges in Venezuela

DiPELT was piloted but not continued for administrative issues and country security challenges.

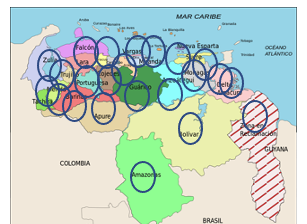

In 2016, a new collaboration was formed with the British Council and the Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Educacion (CENAMEC) who had a language speciality department called ‘Programa Nacional de Formacion Avanzada Lenguas Extranjeras’ (National Programme for Advanced Training of Foreign Languages) or PNFA. As CENAMEC were already established in all 24 States, this gave the programme a much wider reach. The DiPELT programme was re-branded, PNFA, but the other innovations itemised above remained. See figure 4 below for CENAMEC/PNFA training groups.

Figure 4: CENAMEC/PNFA training groups

The PNFA teacher training programme has been accredited by the Ministry of Education (CENAMEC) and the degree is given by the Micromisión Simón Rodríguez and Universidad Nacional Experimental del Magisterio “Samuel Robinsón”. In 2021 the 4th cohort of teachers are taking part in the programme. Teachers’ English language proficiency levels have increased by CEFR +1, so are now CEFR A1/A2. There have been 4 published reports (2017, 2019, 2020 and 2021) identified in the references below.

The numbers impacted since 2016 are:

- 289 tutors and facilitators trained

- 4,277 generalist public primary teachers trained using PNFA courses

- 78,651 public primary school students introduced to English

Training materials

Trainer (Facilitator) and Teacher training materials designed for the PNFA include:

PNFA Facilitator’s Guide (Trainer’s Manual) – Modules 1 to 10 (see Figure 5 below for sample)

PNFA Participant’s Guide (Teacher’s workbook) – Modules 1 to 10 (see Figure 5 below for samples):

Figure 5: samples of a Facilitator’s Guide and Participant’s Guide

Trainer (Facilitator) training materials to cascade training to teachers have also been designed and delivered for classroom materials described below. This includes training when both the PNFA and classroom materials were digitalised in 2020-2021 and training and teaching had to continue remotely due to the Pandemic.

Classroom materials

After a year of the PNFA teacher training and positive feedback from the monitoring and evaluation of learning (M&EL), classroom materials were commissioned for Primary Grades 4 to 6. These materials use a spiral curriculum based on five topics: animals, environment, geography, health, and us. The spiral curriculum ensures recycling both across topics in a grade but also up the grades, so learners come across each topic in greater depth each year, as well as recycling the language they have learnt previously.The learners receive a booklet with all five topics. See Figure 6 below for learners’ booklets.

Figure 6: Classroom learning booklets for learners with 5 topics

There are also five Teacher’s Books per grade, which include a facsimile of the learners’ books plus detailed scripted lesson plans. See Figure 7 below for Grade 4 to 6 Teacher’s books.

Figure 7: Teacher’s books for Grades 4 to 6

Two of the innovations with the classroom materials were:

- Realistic consideration was taken about the level of the teacher’s English language proficiency and the steps for delivering the lesson was written in Spanish, but the classroom delivery instructions and the target learning language was in English

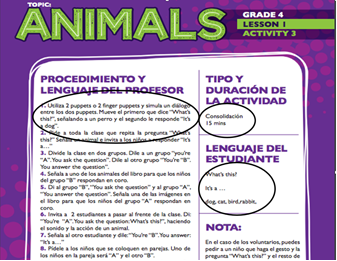

- There were 6 hours of classroom lessons in each topic, these were divided into one-hour lessons, further sub-divided into four fifteen-minute parts. As the teachers are generalist teachers, they teach all the subjects, breaking a lesson into smaller parts gives the teacher more flexibility about when they deliver the English class, it also considers their English language proficiency and their ability to deliver a lot of English at one time. See figure 8 below identifying the steps scripted in Spanish but the deliver language scripted in English.

Figure 8: the steps scripted in Spanish, but the delivery and target language scripted in English

Case study

The goal of the case study was:

“To evaluate the impact of the [PNFA] programme”

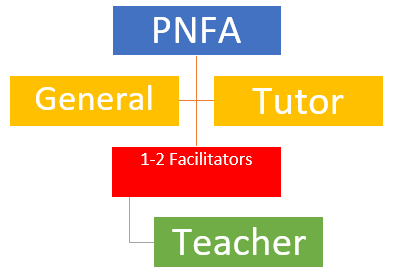

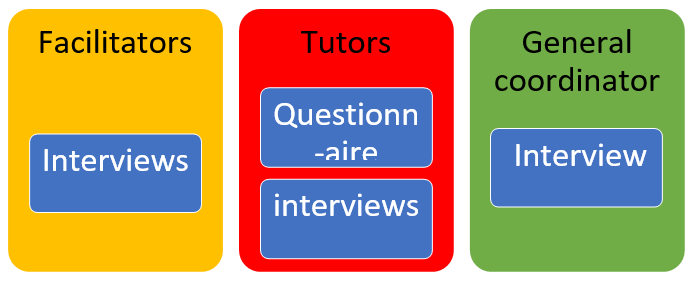

The PNFA programme is delivered by 1-2 ‘facilitators’, these are teacher trainers who have undergone the training for delivering the programme. Each region has a ‘tutor’, who also attends the PNFA teacher training programmes, as well as a ‘general co-ordinator’ who organises the training logistics. Refer to Figure 9 below for the hierarchy of the PNFA regional teacher training programme.

Figure 9: the hierarchy of the PNFA regional teacher training programme.

Methodology

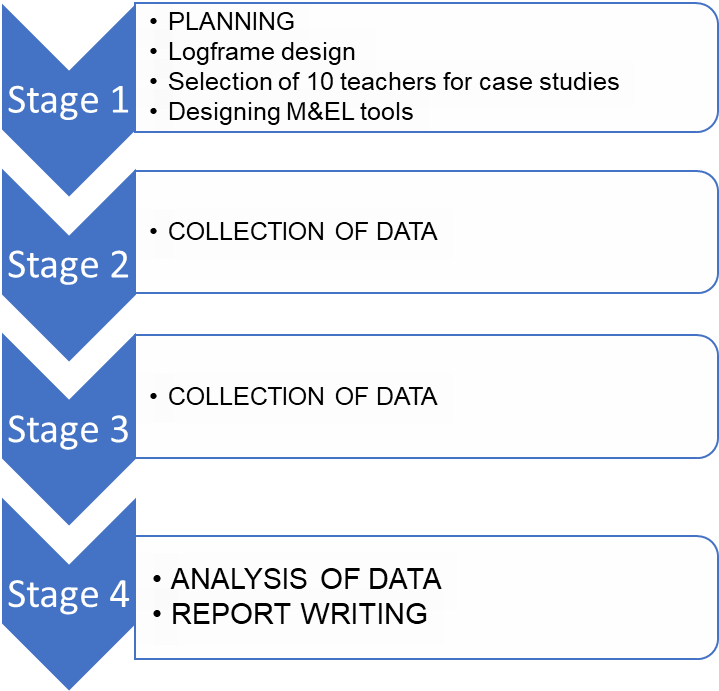

The case study was carried out with Cohort no. 2 of the PNFA training. There were four stages in the M&EL which are described in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10: Four stages of the monitoring and evaluation of learning for the case study

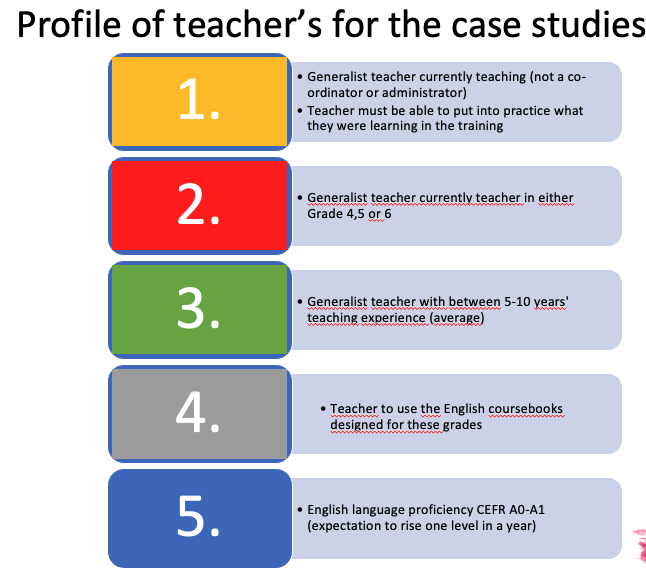

One of the critical aspects of the case study was the selection of the teachers. Refer to Figure 11 for a breakdown of the selection profiles of the teachers.

Figure 11: a breakdown of the selection profiles of the teachers.

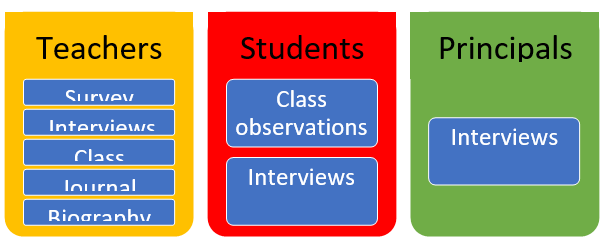

The stakeholders were divided into two groups and data collection tools were designed for each group. Refer to Figures 12 (Group 1) and 13 (Group 2) for a breakdown of the stakeholders within each group and the data collection tools applied.

Figure 12: Data Collection tools – Stakeholders Group 1

For the purpose of reporting the findings, these will be divided into three groups which were impacted by the project, being the teachers, the students and the community.Figure 13: Data Collection tools – Stakeholders Group 2

In addition to the teacher’s selection profiles itemised in Figure 11 above, the researcher needed to ensure that there was a balanced regional selection. Six regional centres were identified, and 1-2 teachers were selected for case studies in each. Refer to Figure 14 to see the case study regions.

Figure 14: Regions where the case studies were carried out.

Findings

For the purpose of reporting the findings, these will be divided into three groups which were impacted by the project, being the teachers, the students and the community.

The teachers

Teaching Strategies

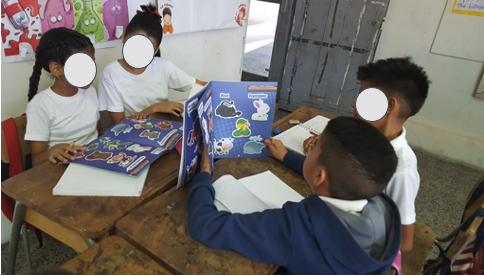

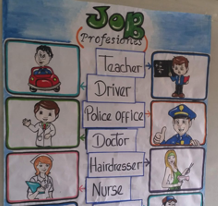

The teachers reported that the strategies they had learnt, during the PNFA teacher training CPD methodology section, also worked for teaching other subjects. These included using pair and groupwork, introducing new games, songs and fun activities, and making their own sustainable teaching resources using recycled carton. Refer to Figure 15 and Figure 16 for some photos exemplifying some of the teaching strategies.

Figure 15: learners working in groups and pairs.

Figure 16: Teacher made teaching resources using sustainable materials, e.g. recycled carton

Attitude

The teachers reported that the PNFA programme had impacted on their general attitude. They were proud of learning a new language and felt that they were doing something useful for their students. The teachers also reported that their own self-esteem increased despite all the challenges they encountered.

Challenges

The teachers reported the challenges they encountered during their teaching, which included:

- students not coming to classes regularly

- the hours of teaching were reduced to 3 hours a day

- there were regular ‘blackouts’ when there was no electricity

- there was no transportation, either gasoline could not be bought for the transport or people had run out of cash to pay for the transport

The Students

Motivation

Teachers reported that the motivation of their students increased, one teacher said:

‘The children love it [English]. They want more and more. They want English classes every day’

Another teacher reported:

‘… children who didn’t bring their assignments started bringing English assignments. I told them ‘if you don’t improve in the other subjects, we won’t have English class’ … surprisingly, they did improve in the other subjects in order to have their English class.

Behaviour

Teachers also reported that the student’s behaviour changed, one teacher reported:

"... . Even their behaviour has had a positive change. If they are misbehaving, I say that I’m not going to teach English today, then, they get quiet immediately.”

Another teacher reported:

"... I have a difficult group. When I say ‘listen’, they pay attention but if I say it in Spanish they do not pay attention to me.

The community

The community being the stakeholders in the school community which included: parents, principals, colleagues, other children, janitors, as well as the school cooks. They were all very supportive of the teaching of English and recognised it as a positive action which they approved. There was also a willingness to take an active part by joining in with greetings.

The School Principals reported that:

“Many parents have come to this school asking for a place for their children to study here because they were told we were teaching English”

“We are really glad. Children now greet us in English.”

“The teacher represented our school, she took all the resources and everybody was surprised in the regional educational event”

Reflections on the findings

The researcher found that they could divide the findings into sub-sections as follows:

- Re-dimension of the roles in the classroom

There was ‘dual learning’. Both the teacher and the student were learning English at the same time and there was an ‘emerging cooperative learning’.

- Empowerment of the teacher

Teachers felt a sense of achievement, they gained status within their school and classrooms. They felt they were doing something positive for others and they were receiving recognition from their family, school authorities, as well as, their colleagues and of course, the children themselves.

- Empowerment of the Student

Students also reported gaining status and confidence in learning a new language.

- Rising Facilitator

There was a group of new Facilitators who were formerly trainees, graduates from the first cohort of the PFNA. These new Facilitators were generalist trained teachers, so were deemed ‘knower of the learning environment’. They had taken part in the training programme and understood its benefits. These Facilitators were highly motivated and very creative. They were very good at identifying strategies which worked. Although, the Facilitators, as generalist trained primary teachers who had taken part in the PNFA training were competent, their English proficiency still needed development. This looping of generalist teachers trained through the PNFA programme makes the project more likely for long-term sustainability.

- General findings

There is a transition towards a ‘communicative’ class. The students are working in pairs and groups as teachers become more confident and they can see that these kinds of social interactions support other types of learning.

The classroom environment has changed, and this trigger supports deeper learning.

There is an integration between the school and the community.

Post-case study innovations to support teachers during the pandemic

The current ongoing disruption to education around the world is going to have a significant impact on the learning of students. Primary students are particularly impacted as they are laying the foundation of their learning. In order to mitigate some of the damage, the British Council commissioned the following innovations:

- Transferring the PNFA teacher training programme onto an app or downloadable on the Canaima’s* so that the training could continue

- Transferring the classroom materials onto an app or downloadable on the Canaima’s* so that teachers could continue to teach online (Note: Canaima’s are laptops given to children and teachers in primary education. The Canaima’s have been made in Venezuela since 2013.)

- Commissioning 5 stories per grade to be delivered by local radio stations. The stories are scripted into five, fifteen minute sessions, to be delivered on a daily basis. The stories are aligned to the topics of the classroom materials for Grade 4 to 6

References

Canaima https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/7647 Accessed: 280621

López de D’Amico, R. & Gregson, M. (2017). Se respira cambio. Transformando la enseñanza del inglés en el sistema educativo venezolano. Caracas: British Council & CENAMEC https://www.britishcouncil.org.ve/sites/default/files/serespiracambio_version_en_linea.pdf

López de D’Amico, R. & Gregson, M. (2019). La Primaria en Venezuela y la segunda lengua: Educación continua. Caracas: British Council & CENAMEC. https://www.britishcouncil.org.ve/sites/default/files/la_primaria_en_venezuela.pdf

López de D’Amico, R. & Hutchinson, R. (2020). Venezuelan Primary English: Empowering teachers and young learners. Caracas: British Council, CENAMEC & UNEM. https://www.britishcouncil.org.ve/sites/default/files/2020-libro-venezuela-primary-english-empoworing-teahcers-and-young.pdf

López de D’Amico, R. & Hutchinson, R. (2021). Experiencias de formación en el área de Inglés durante la pandemia. Caracas: British Council, CENAMEC & UNEM. https://www.britishcouncil.org.ve/sites/default/files/2021-experiencias-de_formacion-de-ingles-en-venezuela-enero2021_def.pdf

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

English in Public Primary School in Venezuela, Experiences 2018-2019: A Case Study

Juana Sagaray and Maria Teresa Fernandez, Venezuela;Wendy Arnold, United Kingdom