- Home

- Various Articles - SEN

- Investigating EFL Instructors’ Experience with Learning Disability (LD) Training

Investigating EFL Instructors’ Experience with Learning Disability (LD) Training

Jimalee Sowell is a PhD candidate in Composition and Applied Linguistics at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She has worked as in English language teacher and teacher trainer over the past fifteen years. Her research interests include disability studies, teaching writing, peace education, genre analysis, large class pedagogy, and teacher education. Email: hbqy@iup.edu

Larry Sugisaki is a PhD student in Composition and Applied Linguistics at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He has worked as a university English professor as well as an English language teacher in Japan. His research interests include disability studies and writing-center studies. Email: jztv@iup.edu

Abstract

It has been estimated that approximately 10 percent of learners have a learning disability (LD). Legislation in many countries has moved toward an inclusive model of education, where students with disabilities (learning, physical, and behavioral) study in general education classes. While legislation has moved towards inclusion, training initiatives might not have kept pace. English language teachers working in as English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts might not have been trained in inclusive teaching pedagogies and might not be specifically trained in assisting students with LDs. The purpose of this study was to find out about EFL instructors’ experiences with LD training. Major findings revealed that many participants indicated they had not received any specific training on LDs (46 percent) and lacked confidence for assisting students with LDs (70 percent). The study also revealed that the preferred formats for training include face-to-face trainings with an expert, short-term training sessions, and access to available resources. The most commonly-desired topic for training was basic training for identifying and assisting students with LDs. Recommendations include the need for more training on inclusive classroom pedagogies as well as training specifically focused on LDs for English language teachers working in EFL contexts.

Introduction

This purpose of this study was to find out about English language teachers’ experience with learning disability (henceforth LD) training. While policies and legislation in many countries have moved toward inclusive education with students with disabilities studying in general education classrooms, training initiatives to guide teachers might not be sufficient. English language teachers working in English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts might be required to work in inclusive classrooms, but they might not have received any specific training on inclusive pedagogy. These teachers might also lack specific training in assisting students with learning disabilities (LDs) in the general education classroom. In 2020, the authors of this article published a pilot study on EFL teachers’ experiences with training on identifying and accommodating students with LDs. Major findings of that study showed that the majority of participants had little or no experience with LD training (Sowell & Sugisaki, 2020). Based on feedback from reviewers of the first study, the researchers made some changes to their initial research instrument before conducting the current study. The current study sought to specifically gain a basic understanding of LD training amongst EFL instructors—whether they had such training, and, if so, what type of training they had taken part in. The researchers also wanted to find out whether the participants felt confident assisting students with LDs in their English language classes. Furthermore, the researchers were interested in learning about the study participants’ preferred methods of training to develop their knowledge and understanding of LDs. This study did not measure teachers’ knowledge and experience with LD training against the backdrop of any country’s specific laws and legislation or current educational practices, but instead sought to gain a general understanding of EFL instructors’ experience with LD training across contexts and countries. The results of this study can benefit policymakers, administrators, teacher trainers, and disability support services.

Literature Review

Defining Learning Disabilities (LDs)

The term learning disability was first defined by Samuel Kirk (1962) in his book Educating Exceptional Children. Since the publication of this book, there has been a great deal of controversy regarding definitions of learning disability as well as the terminology used to describe it. Currently, terminology often differs according to the country and sector in which the term is used. For instance, while specific learning difference is commonly used in the education sector in the UK (Kormos, 2017) specific learning disability or learning disability is used in US schools and legal systems (APA, n.d.). For the purposes of this article, the authors use the term learning disability (LD). A perfect definition with agreement from LD researchers and scholars may never exist. As a broad conceptual construct, however, Fletcher et al. (2007) have defined LD as unexpected underachievement. Burr et al. (2015) have specifically defined LD as “A neurological condition that interferes with an individual’s ability to store, process, or produce information. LDs can affect a student’s ability to read, write, speak, spell, compute math, or reason as well as a student’s attention, memory, coordination, social skills, and emotional maturity” (p. 3). Common to all students with LDs is considerable difficulty in at least one area of academic performance. Difficulties in developing literacy constitute the most common forms of LDs (Klingner & Eppolito, 2014; Pierangelo & Guilani, 2010). When determining whether a LD is present, it is important that other factors which might result in academic underperformance be eliminated. The Learning Disabilities Association of America (LDA) stated that “Learning disabilities should not be confused with learning problems which are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor handicaps; of intellectual disability; of emotional disturbance; or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantages” (Learning Disability Association of America, 2018, para. 3).

Inclusive Education

Inclusive education focuses on making schools an effective learning place for all students, no matter their differences. For students with disabilities, an inclusive education means access to the common curriculum in the general education classroom (Bryant et al., 2019; Mastropieri & Scruggs, 2017). Inclusive education has been interpreted in different ways, and, consequently, has been implemented in different ways. In some iterations of inclusion, students with disabilities receive all instruction in the same settings as other students. This practice is referred to as full inclusion. Full inclusion might include pull-in programming where students with disabilities receive some instruction from specialists in the general education classroom (Bryant, et al., 2019; Mastropieri & Scruggs, 2017). For instance, a speech pathologist or language therapist might work with some students in the general education classroom, or a special education instructor might co-teach with content teachers in the general education classroom. In another iteration of inclusion, students with disabilities receive some instruction outside the general education classroom. This is referred to as pull-out programming and could include resource rooms, special classes, and special education schools. While it was once thought that students with disabilities could perform better when educated in “special schools,” research has shown that educating students with mild or high-incidence disabilities in inclusive classrooms is effective for all students (Bulat et al., 2017; Cole et al., 2004; National Institute for Urban School Improvement, 2000; Rapp & Arndt, 2012). In an inclusive classroom, students with varied abilities learn to interact with each other, an important part of learning to be inclusive. However, students with more severe disabilities might still need to be educated in separate classrooms or schools (Rapp & Arndt, 2012), and the inclusive model might not be effective for all students.

While inclusive education has shown positive results for many students, simply placing students with disabilities in general education classes, does not guarantee successful learning outcomes (Zigmond, 2003). Instructors of inclusive classrooms often need to implement pedagogical approaches designed to help all students succeed. Teachers of inclusive classrooms might follow a framework such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Other inclusive techniques and strategies might include differentiated instruction, explicit instruction, and use of assistive technologies along with other inclusive classroom management strategies (Bryant et al., 2019; Rapp & Arndt, 2012). In addition to being able to implement inclusive pedagogies, content teachers can be benefitted by having a general understanding of how students with mild to moderate LDs can be helped in the general education classroom. Disabled students might need certain accommodations to effectively access the general curriculum (Zigmond, 2003). Training of content teachers in inclusive pedagogies as well as basic methods and techniques for identifying and accommodating students with LDs could help students with LDs succeed in the general education classroom.

History of inclusion in the US and the UK

Historically, in some countries, there has been a movement from denial of educational rights for students with disabilities to special education (which often meant students with disabilities studied in separate locations, apart from regular classrooms) to inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms (Rapp & Arndt, 2012; Smith, 2006). In the United States, prior to the 1970s, some children with disabilities were denied access to public education (Bryant et al., 2019). In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHC) was passed. In 1990, this act was renamed as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. In 2004, it was changed to the Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA). Each reauthorization was accompanied by different iterations and changes, but still focused on the rights of all children to access public education. In the UK, a similar process has taken place. Movement towards educating students with disabilities alongside able-bodied peers began with the Education Act of 1944. The 1970 Education (Handicapped Children) Act recognized that all children had the right to education. The 1981 Education Act laid the framework for shifting from separatist special education towards inclusion. In 2001, the Special Needs and Disability Act was intended to further support effective inclusion. This was followed by Every Child Matters legislation in 2004 (Lauchlan & Greig, 2015).

The authors of this study mention the general history of approaches towards education for disabled learners in the US and UK to provide a general idea of how these countries have approached educating students with disabilities. Some countries represented by participants in this study may have followed a similar trajectory towards inclusion. However, other countries might have only adopted inclusive practices recently and might not yet have a robust support system in place. In some countries, there might be a gap between laws requiring inclusive education and the tools and resources teachers have available to successfully implement it in their classrooms. While a lack of funding and available resources (including available experts), might create obvious barriers to inclusive education, in some contexts, cultural values might also play a role. Developed countries might serve as models of legislation and practices of equitable education, but each country must consider its own cultural perspectives when developing legislation and polices (Halder, et al., 2017).

International Human Rights and Inclusive Education

The United Nations Education for All (EFA) movement was principled upon making basic education available to all. Established in 1990, the EFA movement sought to identify barriers to education and to remove them. This movement was furthered with the Salamanca Convention. In June 1994, more than 300 representatives from 92 governments and 25 international organizations met for the World Conference on Special Needs Education in Salamanca, Spain to further develop and refine policies of the Education for All movement by examining the policy changes needed to promote inclusive education (Ainscow, 2020). A Framework of Action was developed at the Salamanca Convention, the guiding principle of which stipulated that regular schools should educate all children regardless of physical, intellectual, social, linguistic, or other conditions, with the exception of students with severe needs that require more specialized support (UNESCO, 1994). The Salamanca Framework detailed actionable items governments should implement to support inclusive education. Alongside policies and funding for inclusive education, the Framework of Action specified the need for pre-service and in-service training on inclusive teaching pedagogies (UNESCO, 1994).

A little over a decade later, in 2006, The Convention on the Human Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations, 2006) established that persons with disabilities (both learning and physical disabilities) are entitled to the same rights and freedoms as all others. The CRPD outlined protections that must be in place along with accommodations or adaptations that might be required so that persons with disabilities are granted the same rights as all others. Article 24 of the CRPD states that persons with disabilities have the right to education and that governments have the responsibility to provide inclusive education with adequate accommodation and support services for persons with disabilities. Developed from the Incheon Declaration at the World Forum on Education in 2015, UNESCO published the 2030 Framework for Action, which emphasizes inclusion and equity as important principles for quality education (UNESCO, 2015).

Despite movements toward inclusive education, barriers to education for persons with disabilities still exist. Data from the World Health Survey showed that fewer students with disabilities finish primary school and that disabled students, on average, have fewer years of education than their non-disabled peers (WHO, 2011). Disability Rights Promotion International (DRPI), an international organization that monitors the rights of persons with disabilities, has reported that in many countries, both high- and low-income, many children with disabilities do not attend school and receive little to no education (DRPI, 2014). Disabled students who do attend schools are often placed in separate schools or segregated classrooms, or they are not provided with teaching methods and materials suitable for their needs (DRPI, 2014).

Lack of training as a significant barrier to Inclusive Education

While there are numerous factors that may present barriers to inclusive education, one of the most critical relates to training. In spite of initiatives to make schools more inclusive, several researchers (e.g., Al-Busaidi & Tuzlukova, 2018; Alkhateeb, 2014; Forlin, 2006; Huang, 2011) have found that teachers lacked sufficient training in inclusive teaching practices. Not only do teachers who are not adequately trained often have difficulty meeting the educational needs of students with disabilities (Halder, 2008, 2009), but, additionally, teachers without sufficient training often develop an unfavorable view of inclusion (Corbett, 2001; Kristensen et al., 2003; Reid, 2005; Winter, 2006). Smith (2006) has pointed out that there are various barriers to training. Funding limitations might prevent the implementation of training programs. In some locations, there are not enough specialized experts to deliver the needed training. Institutions themselves might thwart training initiatives by not providing teachers enough time off to attend training sessions.

Additional barriers to training sometimes come from teachers themselves. Some teachers might resist inclusive education because they do not believe that students with disabilities should be educated in the same classrooms as their abled peers (Al-Busaidi & Tuzlukova, 2018; Smith, 2006). In some contexts, this resistance might relate to cultural beliefs (Hassanein, 2015; Singal, 2008), which are part of the larger social context. Lack of community support of inclusion and negative attitudes towards disabilities can present major challenges to inclusive education in some contexts (Hassanein, 2015; Singal, 2008). Singal argues that not only is there a need to provide teachers with training in inclusive practices, but also a need to challenge existing cultural beliefs about disabilities. Ainscow (2020) argues that for inclusion to work, it must become a part of the fabric of the community. Governments need to foster relationships with key stakeholders which include parents, teachers, policy-makers, and administrators (Ainscow, 2020).

Previous research on Learning Disability Training in EFL Contexts

To date, little previous research has focused specifically on learning disability training of English language teachers in EFL contexts. In a pilot survey study of 94 primary school EFL instructors in Northern Greece, Lemperou et al. (2011) found that nearly half of the respondents (45 percent) indicated they had little knowledge of dyslexia and how it affects language learning; however, the majority (87 percent) indicated a willingness to attend training seminars on dyslexia. Huang’s (2011) qualitative study of five in-service special education EFL teachers in Taiwan suggested the need for more teacher education training programs focusing on inclusive education with content on teaching students with LDs. In our own previous research (Sowell & Sugisaki, 2020) with former and current EFL instructors, the majority of study participants (83 percent) did not feel confident in their ability to assist students with LDs, with 57 percent of study participants indicating they were not sure whether they possessed the knowledge and skills to teach learners with LDs. In the same study, among the respondents who had received training on LDs, the majority (52 percent) indicated that the training they had received had been minimal—lasting a day or less.

Methods

Research Sites and Data Collection

After receiving Institutional Research Board (IRB) approval from Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), the researchers sought to collect data from two venues. The researchers distributed their survey through IUP’s listserv to MATESOL students and Composition and Applied Linguistics PhD students. The researchers targeted these two programs because, among all IUP programs, they were they most likely to have students with experience teaching in EFL contexts. In addition to distributing the survey to current IUP students, the researchers also posted the survey link to a closed social media group exclusively for current EFL teachers working in different countries around the world.

The following research questions guided the data collection for this study: 1. What training (if any) did the study participants have for assisting students with LDs? 2. Do participants feel confident in their ability to assist students with LDs? 3. What type(s) of LD training would participants like to have? 4. What are the participants’ perceptions of the importance of LD training?

All data for this study were collected via Qualtrics software. The survey contained 12 questions: 10 closed-ended questions and two open-ended questions. The survey was open from June 15, 2020 to November 11, 2020. When the researchers closed the study, 106 responses had been collected. However, 11 of the 106 surveys were not complete. All incomplete responses were deleted prior to analyzing the data (Hittleman & Simon, 2006). In total, 95 completed responses were analyzed.

Data Analysis

Closed-ended questions were analyzed with descriptive statistics using SPSS software. Open-ended questions were coded using the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), which “involves multiple rounds of coding in which codes, categories, and patterns are generated, compared, evaluated, and refined” (Polio & Friedman, 2017, p. 210). After reading the raw data a few times, the researchers engaged in initial coding. By reading the data line by line, the researchers developed initial codes and sub-codes. The researchers then compared “data with data, data with codes, and codes with codes” (Thornburg & Charmaz, 2012, p. 78) to establish the more frequent and important codes. At this stage, some codes were refined. Once codes and subcodes were established, the researchers then counted the frequency of the codes and selected representative examples for each code.

Results

Question 1: Question 1 explained the study and asked for consent. Those who did not consent to the study were automatically exited from the survey.

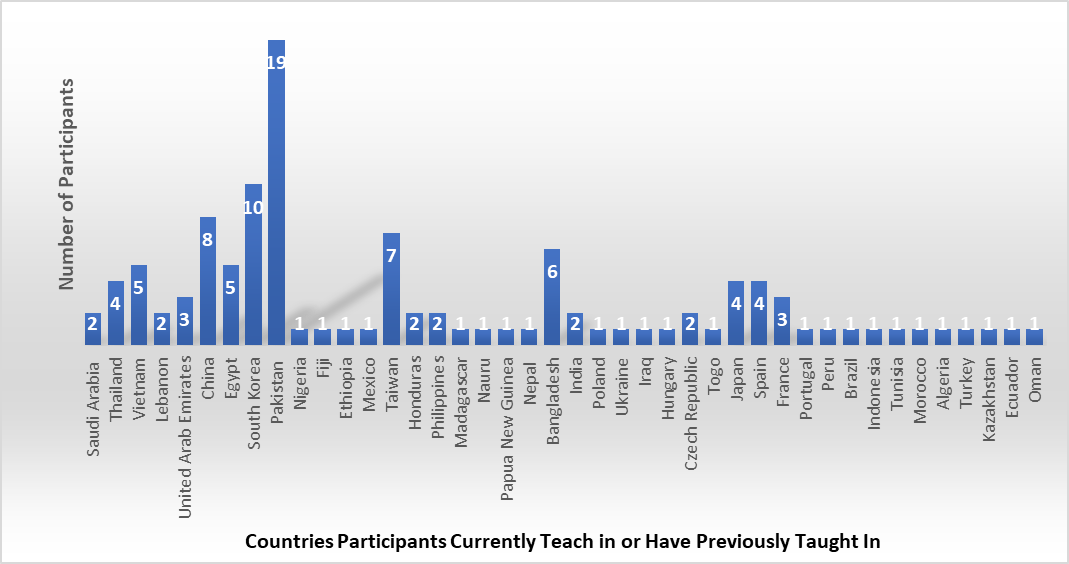

Question 2: Please indicate the country you currently teach in or the countries you have taught in previously.

The purpose of this question was to ensure that the participants in the study had EFL teaching experience and to verify whether the population of participants was representative of a number of countries. Pakistan had the most representation (19), followed by South Korea (10), China (8), Taiwan (7), Bangladesh (6), Vietnam (5), Thailand (4), Spain (4), Egypt (4), Japan (4), and France (3). All other countries had one or two participants. In total, 42 countries were represented.

Figure 1. Countries Participants Currently Teach in or Have Previously Taught In

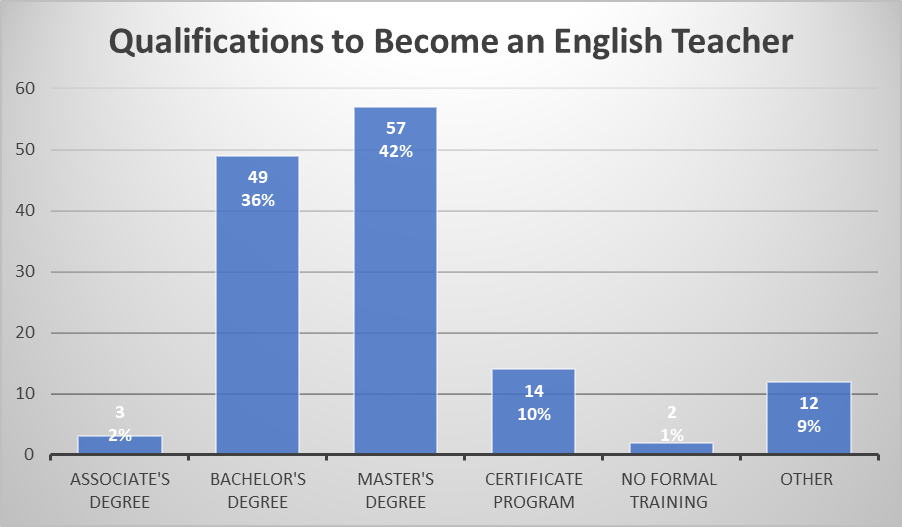

Question 3: What specific formal training have you received to become an English language teacher? Check all that apply.

This question was meant to provide a general idea of the level of education of the study participants to qualify them as English teachers. Study participants were allowed to check multiple responses to this question as they might hold various qualifications. One hundred thirty-seven responses were recorded. The majority of participants (42%) were master’s degree holders. This was followed by participants with a bachelor’s degree (36%), a certificate program (10%), and an associate’s degree (2%). One percent indicated they had no formal training. Nine percent of participants indicated training for English language teaching not listed among the answer choices. Amongst the nine percent who had checked “other,” 4 percent had obtained a PhD or were PhD candidates; 0.73% had completed an advanced certificate in ELT; 0.73% indicated they had completed master’s degree coursework but had not graduated; 0.73% had completed online courses; 0.73% had advanced certification in ELT; 0.73% had American English training; and 0.73% had begun teaching with a BA but no formal qualifications in English language teaching.

Figure 2. Qualifications to Become an English Teacher

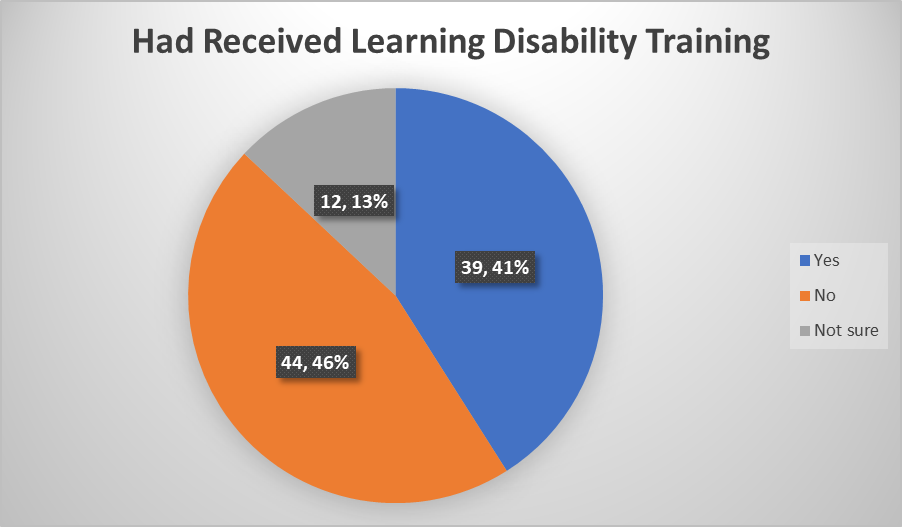

Question 4: Have you received any training on how to assist students with learning disabilities?

The majority of participants (46 percent) indicated they had not received any training on methods for assisting students with LDs. Forty-one percent of participants indicated they had received training on LDs. Thirteen percent of respondents were not sure whether they had received any LD training.

Figure 3. Had Received Learning Disability Training

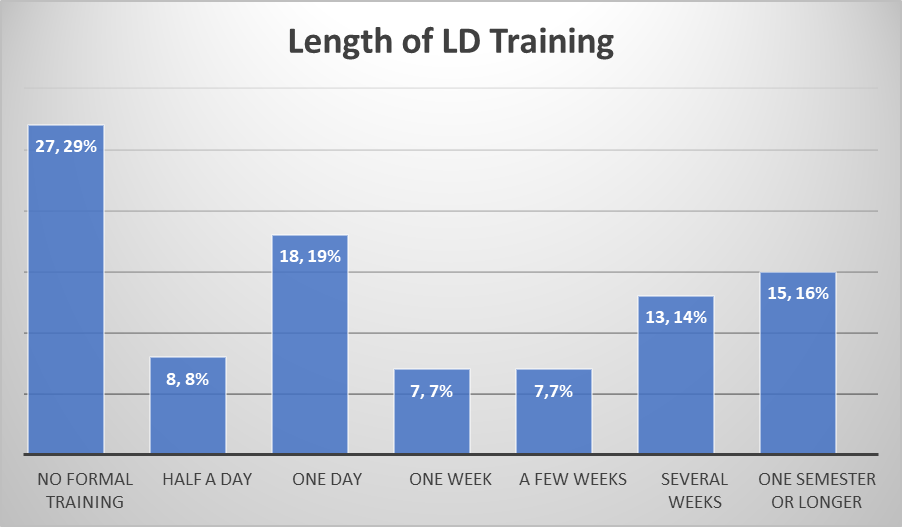

Question 5: In total, what was the length of your training?

The largest number of participants (29 percent) indicated they had not received any sort of formal training. This was followed by a one-day training (19 percent). Training that lasted four-to-eight weeks came in at 14 percent as did training that lasted one semester or longer. Eight percent of participants had engaged in a half-day training. Training lasting one week and training lasting a few weeks both garnered 7 percent of responses.

Figure 4. Length of LD Training

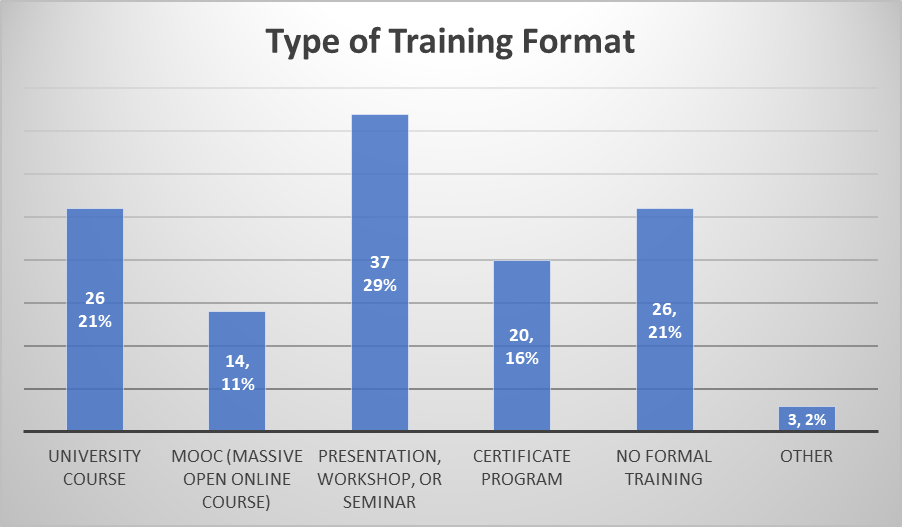

Question 6: Which class format most closely describes the training you have received?

The largest number of participants (29 percent) received training through some sort of short-term training: a workshop, seminar, or presentation. This was followed by training through a university course (21 percent) and no formal training (21 percent). Sixteen percent of respondents had participated in some sort of certificate program. Eleven percent of participants took part in a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Two percent of participants indicated “other.” Among the other responses, one participant had learned about LDs in a course on writing centers and while working in a writing center. Another participant had taken part in a mentorship program which offered a brief presentation by the director of the disability office to explain how teachers could refer students. One participant simply mentioned teacher training but provided no details.

Figure 5. Type of Training Format

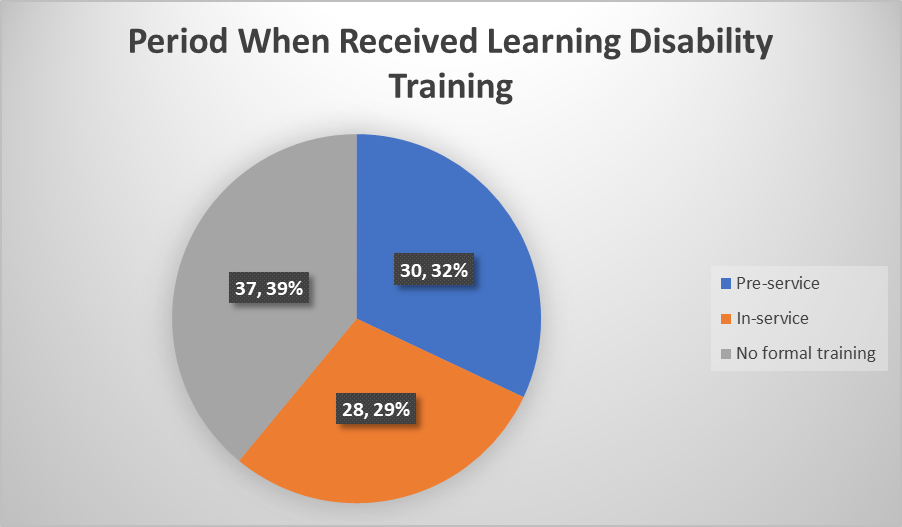

Question 7: When did you receive the majority of your training?

The majority of participants indicated they had received no formal training (39 percent). Responses for pre-service and in-service training were nearly the same with 32 percent of participants indicating they had received training on LDs during pre-service training, and 29 percent indicating they had received learning disability training while working as in-service teachers.

Figure 6. Period When Received Learning Disability Training

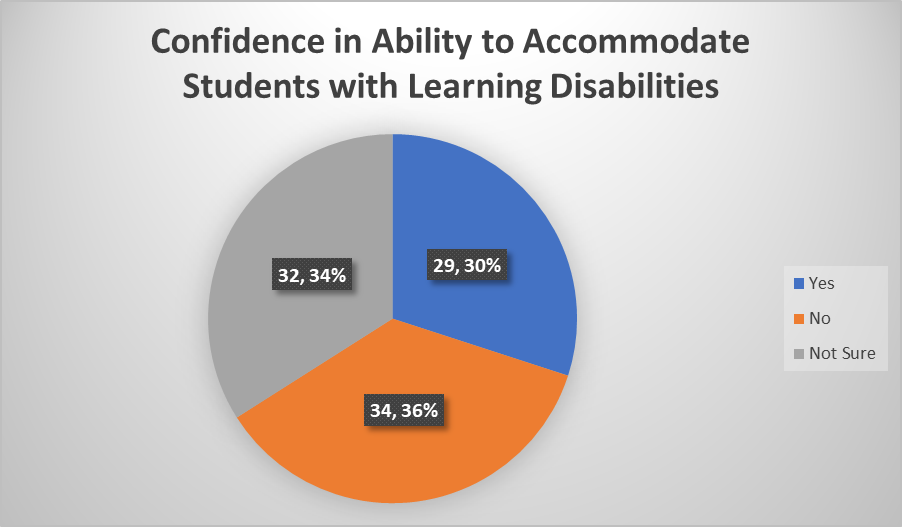

Question 8: Do you feel confident in your ability to accommodate students with learning disabilities in your classroom?

Thirty-six percent of respondents indicated that they did not feel confident in their ability to assist students with LDs. Thirty percent reported that they do feel confident in their ability to accommodate students, and thirty-four percent were not sure whether they felt confident accommodating students with LDs.

Figure 7. Confidence in Ability to Accommodate Students with Learning Disabilities

Question 9: What type of training do you think would be most beneficial to you in terms of improving your understanding and performance in accommodating students with learning disabilities?

Question nine was an open-ended question. Responses were coded and are listed in the table below.

Table 1. Desired Format of Training

Desired Format of Training

|

Codes |

Number of Participants with Particular Code |

Examples |

|

Theory and Practice |

|

|

|

Training with a Practical Aspect |

5 |

A. This should be supported by some real-life classes (application) where I can actually apply what I learned in a real classroom. B. Training in natural environment, where, instead of bookish language, practical usage is preferred. C. Theoretical training then observation during implementation then follow up and evaluation/feedback for improvement. |

|

Resources |

|

|

|

Training with Institutional Resource Support Representatives |

3 |

A. A Q & A session with our school or institution’s disability services office. Sometimes I feel there is a disconnect between teachers of students with learning disabilities and the disability office. Like we are given a paper with their list of accommodations and are just expected (without training) to be able to implement, adjust our course, and accommodate these students without any training or help form the disability office. B. What would be helpful to me is understanding and knowing what resources or help can be offered to not only a student with learning disabilities, but the teacher who teaches him or her. |

|

Resources on LDs |

15 |

A. I think an online guide or resource that could give me a very clear explanation of key signs of a specific learning disability and ways/tools to help students in my classroom overcome these disabilities from a teacher’s standpoint would be very helpful. B. I believe the most beneficial type of training I could receive is a resource I could turn to—online resource, textbook, or PowerPoint, etc. C. I think having a textbook, online resource we teachers are aware of that we can easily access and get proper assistance in not just identifying a specific disability but a clear explanation (online for face-to-face from an expert) on how to best help a student within my class at the tasks that will and do come up in my course. |

|

Face-to-Face Training |

|

|

|

Interaction with a Learning Disability Expert |

20 |

A. Face-to-face given by teachers who know about language teaching, usually the training is given by psychologist. B. I think continually being updated by personal and teaching experts in my region on the most current and up to date methods, approaches, and training on how to best accommodate students with learning disabilities is something I would want. C. I want some face-to-face training where I am being taught by a disability expert and most of all, have the opportunity to ask questions. |

|

Peer-Discussion and Support |

4 |

A. I say we share the experiences of others, I mean teachers who have been through the same thing. They can tell us their stories and what did they do and learn, and share the information with others. B. Q & A session talking with teachers who have personal experience working with and accommodating students with learning disabilities in their classroom. Being able to ask them questions and getting input of not only them, but other teachers at the session. |

|

Courses |

|

|

|

Online Courses (MOOCs and Regular Online Courses) |

8 |

A. Online courses B. MOOCs |

|

Content Course |

2 |

A. I think it would be useful if teacher candidates could receive content courses related to addressing the needs of students with learning disabilities during their college education. B. A particular course that could best describe the techniques and strategies for teaching students with disabilities. |

|

Ongoing Training |

|

|

|

Regular, Ongoing Training Sessions |

4 |

A. I wish we could have some sort of monthly teacher meetings where we could ask other teachers or disability experts for help, suggestions, and how other teachers have accommodated students with LDs. B. Being able to attend a yearly training over several days where we can get some sort of presentation on various topics related to learning disabilities and how to help students with learning disabilities would be very helpful. C. On-going workshops on recent research and best practices. |

|

Short-Term Training |

|

|

|

Workshops, Seminars, or Presentations |

15 |

A. Workshops that include teaching, small group discussions, group problem solving, and sharing. B. I prefer to get training in workshop-style environment where I am able to ask questions if I have any to a presenter or expert on the topic of learning disabilities. D. Face-to-face training in the form of presentations, workshops, and seminars. |

Table 2. Desired Topic of Training

Desired topic of training

|

Coordination Between Institution and Teachers |

|

|

|

Technology |

|

|

|

How to Incorporate Technology to Accommodate Students with LDs |

4 |

A. I think being educated and taught how to incorporate technology into my class to accommodate students with different learning disabilities would be helpful. B. Learning specific types of applications or technology is available to help make content accessible. |

|

Basic Training |

|

|

|

How to Identify and Assist Students with LDs |

33 |

A. For me and my colleagues, I believe the best way to service and teach students with types of learning issues, we as teachers need to be able to know the basic types of learning disabilities, how it impacts a student’s learning, and what steps the teacher and school can take to make the student successful. B. I would also like to know how a learning disability impacts a student’s learning so I can teach around this disability and accommodate the student as best I can. C. For each particular type, how do we as teachers accommodate that student. I want this particular type of information. What is their disability’s characteristics/symptoms and how we best accommodate them? |

|

Inclusive Classroom Pedagogy |

|

|

|

Effective Teaching Techniques for an Inclusive Classroom |

7 |

A. Learning how to make my lesson plan more inclusive and accommodating for students with learning disabilities would be very helpful. B. How to engage students with disabilities without making them feel bad of being in such situation. C. Steps and guidelines I could take in editing and adjusting my course material and course as a whole to allow students the best opportunity to succeed. |

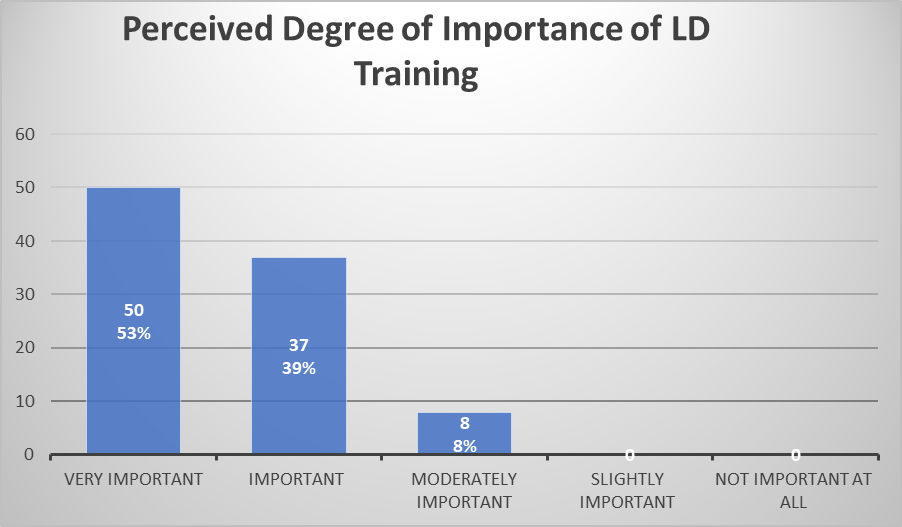

Question 10: How important do you think it is for English language teachers to have learning disability training?

Most participants in this study indicated that they believe training on LDs is important, with most participants indicating that LD training is either very important (53 percent) or important (39 percent). Eight percent felt that LD training is only moderately important. No respondents indicated they felt that LD training is only slightly important or not important at all.

Figure 8. Perceived Degree of Importance of LD Training

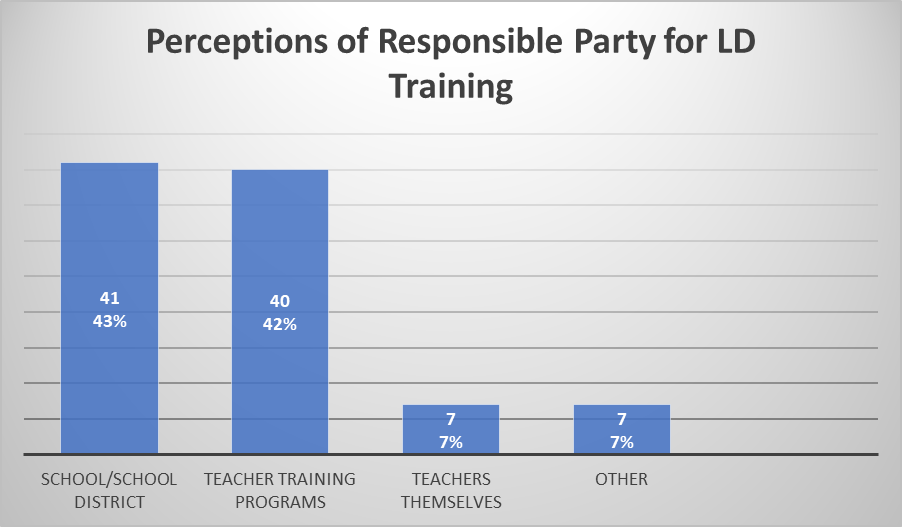

Question 11: Who do you think should be responsible for carrying out learning disability training?

Most respondents (43 percent) felt that it is the responsibility of the school district to provide training on LDs. This was closely followed by the belief that the responsibility for LD training should be held by teacher training programs (42 percent). Only seven percent indicated they believed teachers themselves should be responsible for learning about LDs by independently seeking out resources and training opportunities. Seven percent of respondents checked “Other” in response to this question. Among the “other” responses, five percent of respondents indicated that school districts, teacher training programs, and teachers themselves should share the responsibility for LD training. One percent suggested that NGOs should be responsible for LD training, and one percent suggested that school districts should provide financial incentives for teachers to take part in LD training initiatives and should fund professional development workshops and conferences.

Figure 9. Perceptions of Responsible Party for LD Training

Question 12 provided participants the space to add any further comments on LD training not previously covered in the survey.Question 12: Is there anything else you would like to say about learning disabilities or learning disability training?

Table 3. Participants’ Further Comments on LD training

|

Codes |

Number of Participants with Particular Code |

Examples |

|

Training |

|

|

|

A. A Need for Training |

22 |

A. I think it should be included in a teacher training program. B. So, it is really best to attend trainings on learning disability to realize the goals of inclusive education. C. As higher education continues to educate the masses, it will be increasingly important to receive training in this area. |

|

B. Recognition of the Need to Educate Oneself About LDs |

2 |

A. Thus, it is a wise idea for language teachers to educate themselves about learning disabilities. B. I am becoming increasingly aware of its importance. I think I’ll try to find a course online to take if my workplace fails to train us properly. |

|

C. Short-Term Training May Not Be Sufficient |

4 |

A. I believe that for me as a teacher to be significantly more confident in accommodating a student with a learning disability, a half or single day of training may not be enough. I think a training over several days is more helpful. B. I think having a single workshop or training day dedicated to the subject of learning disabilities is not enough. C. I think learning disability training is not just some topic that can be crammed into one workshop or a single day. |

|

Support |

|

|

|

A. Lack of Support from Institution for Supporting Students with LDs |

7 |

A. Some of these disabled children find almost nobody to take them to schools, youth clubs, or for entertainment. B. Schools have accommodations programs but the last two institutions I have worked for don’t tell how teachers need to accommodate. C. I feel in many cases, the schools we work at try to help us, but can do so much more. |

|

B. Need for Explicit Information on Laws and Legislation |

2 |

A. As an English teacher in a foreign country, what is the best way to go about the country’s legislation and view on learning disabilities? A guideline would be helpful. B. Within the context of the countries I have taught in, is their learning disability laws and legislation similar to my home country, and what is the extent of the accommodation I can provide would be nice to know. |

|

Impact of Culture |

|

|

|

Culture Not Accepting of Disability |

4 |

A. A vast majority of the students I taught were not diagnosed as having a learning disability because the culture that they lived in ignored them completely. B. In my country, we do have many people and especially children with disabilities who [are] neglected by their [parents]. B. I feel there still exists a certain discourse that hinder students with (learning) disabilities from participating in (regular) schools. |

Discussion

Lack of training

Reponses to questions focused on discerning whether participants had LD training showed inconclusive results. In response to question 4, which directly asked participants whether they had any training on LDs, 46 percent of participants indicated they had not received LD training. However, in response to other questions where participants could select “I have not had any learning disability training,” among other choices, answers varied in percentages. For question 6, 29 percent indicated no formal training; for question 7, 26 percent indicated no formal training, and for question 8, 39 percent of respondents indicated no formal training. Across survey items, 26 percent to 46 percent of respondents indicated they had no training on LDs.

While 41 percent of study participants indicated that they had received some sort of LD training, (question 4), only 30 percent of study participants indicated they felt confident in their ability to accommodate students with LDs (question 8); 36 percent indicated they were not confident, and 34 percent were not sure about their ability to accommodate students with LDs. This means that 70 percent of study participants were either unsure of their ability to help students with LDs or were sure that they did not know how to assist these students. These results were not too far from our pilot study in which 17 percent of participants indicated they felt confident helping students with LDs and 83 percent did not (Sowell & Sugisaki, 2020). The previous and current study provide a strong indication for the need for LD training among EFL instructors. Respondents themselves seemed to understand the need for LD training. In response to question 12, that gave participants the opportunity to leave final comments, the most frequent response was that there is a need for LD training.

Level of education

The majority of participants in this study (63 percent) had achieved a high level of education (question 2) with 57 percent holding master’s degrees and 4 percent PhD holders or PhD candidates. Only 1 percent indicated they had no formal training for being an English teacher. This shows that LD training for EFL teachers does not necessarily have a relationship with level of education.

Limited training

A. Format of training

Among those who had received LD training, the majority (29 percent) indicated they had taken part in some sort of short-term training such as a workshop, presentation, or a seminar. This was followed by a university course (21 percent) and a certificate program (16 percent). Only 11 percent had taken a MOOC. These results could be an indication that many participants had only taken part in short-term trainings. Even those who had some LD training during a university or certificate course might not have taken a full course on LDs but might have only had a small part of the course dedicated to LDs, such as a module or assigned chapter with a few pages on LDs. While MOOCs might currently be one of the most accessible forms of training in terms of flexibility of use and cost, some participants might not have been aware of them.

B. Length of training

When asked to indicate the length of their training, 41 percent of respondents indicated they had taken part in relatively short-term training that lasted from a half day to a few weeks; 30 percent had taken part in a longer training lasting from several weeks to one semester or longer. While the short-term trainings might have been a good introduction to effective techniques for working with students with LDs, short-term trainings might not have provided participants with sufficient training to effectively support students with LDs. Smith (2006) found that indeed longer trainings were more beneficial in helping teachers learn to assist students with LDs and physical disabilities. Length of training might offer some explanation as to why 41 percent of participants indicated they had LD training, but 70 percent were either not sure about their ability to assist students with disabilities or were sure that they did not know how to help these students. In response to question 12, some respondents mentioned that short-term trainings, such as a one-day workshop, might not be sufficient.

C. When training was received

When asked when training had been received, most participants (39 percent) indicated that they had not received any training. Among those who had received training, 29 percent indicated they had received their training while working as in-service teachers while 32 percent had received training on LDs during pre-service training. The Framework of Action specified the need for pre-service and in-service training on inclusive teaching pedagogy (UNESCO, 1994). While training on a larger scale is needed for both pre-service and in-service teachers, this result shows that training is being carried out in both pre-service and in-service training initiatives. This does not necessarily mean that the same teachers are receiving both pre-service and in-service training as would be ideal.

Impact of Culture

Some participants pointed out that attitudes toward disability are affected by the local culture (Question 12). One participant mentioned that students with LDs are generally not recognized and provided with proper accommodations because the culture they live in refuses to recognize the existence of LDs. This relates to Singal’s (2008) point that for inclusion to be successful, additional work needs to be carried out to change attitudes and beliefs about disabilities so that students with disabilities are not “othered” but are a part of the classroom. Successful inclusion does not happen just within schools. Community involvement is an important aspect of making inclusion work (Ainscow, 2020), and this involvement might require shifts in thinking. Teachers who do not feel that their culture is supportive of disabilities might find it difficult to implement inclusive pedagogies even when they are knowledgeable about them. Some teachers working in such cultures might also be reluctant to take part in trainings that would help them learn how to better assist students with disabilities, including LDs (Hassanein, 2015; Singal, 2008). Training initiatives need to look beyond just focusing on teachers and find ways to involve relevant stakeholders.

Preferred types of training

This study provided an indication of the types of training EFL teachers would like to participate in. Preferences were indicated through an open-ended question, so responses often exhibited some overlap. Responses were categorized according to the training format preferred and preferences for topics to be covered. The most desired training formats were trainings conducted by a LD expert; short-term trainings in the form of workshops, seminars, or presentations; and access to available resources on LD training. Many participants indicated interest in available resources, such as textbooks or websites. Some participants indicated a preference for online courses (both regular online courses and MOOCs). Some respondents indicated a preference for training with a practical aspect. Some respondents were interested in training involving peer discussion and support with other teachers. A few participants pointed out the importance of training involving institutional resource support representatives. A few respondents indicated that a content course on LDs would be valuable.

Ideally, teachers would be able to access different types of trainings. Workshops can be particularly useful training formats because they provide a platform for participants to interact with a topic expert as well as opportunities for workshop attendees to share knowledge and experiences with colleagues (Sowell, 2016). Online courses could be useful because they offer a certain amount of flexibility. Participants who indicated a preference for practical training might prefer a “learning by doing” approach that dates back to Dewey (1938); but has been an important aspect of many educational approaches, such as experiential learning and activity-based learning. Available resources, such as textbooks and websites, could be a great way for English language teachers to access information as needed, when needed. For some teachers, such resources might be the only way they could obtain information on LDs. In other instances, these resources might work in tandem with other types of training such as workshops or online courses.

The most requested topic was for basic training on how to identify and assist students with LDs. Respondents’ interest in basic training indicates that teachers might have received little training on LDs or that the training they received had not been sufficient. The second most-desired topic was effective teaching techniques for an inclusive classroom. While teachers might be working in schools with inclusive classrooms, they might not have received enough training on inclusive classroom pedagogy (Al-Busaidi & Tuzluova, 2018; Alkhateeb, 2014; Forlin, 2006; Huang, 2011; Singal, 2008, 2009). A few respondents were interested in learning how to use technology to accommodate students with LDs. Knowledge of use of technology with students with LDs could possibly help teachers further assist some students.

Perceived importance of LD Training

The majority, 92 percent of respondents, indicated a belief that LD training is important, with 53 percent believing it is very important, and 39 percent believing it is important. Only 8 percent indicated they believe LD training is only moderately important. No participants indicated a belief that LD training is not very important or not important at all. This shows some alignment with Lemperou et al.’s (2011) study whereby teacher participants demonstrated understanding of the importance of training for their own development. This recognition might have arisen from participants’ experience teaching students with LDs in their classrooms. Some participants might recognize shortcomings for effectively assisting students with LDs, and some participants might have realized that the training they have taken part in has helped them more effectively work with students with LDs. Taking part in this survey might have encouraged some participants to reflect on their knowledge of LDs and techniques to accommodate them which might explain why, in response to Question 12, a few participants indicated the need to educate themselves about LDs. This recognition might encourage some participants to actively seek out opportunities to develop their understanding of LDs.

Perceptions of responsible party for Learning Disability (LD) training

The majority of participants believed that either the school or school district should be responsible for training (43 percent) followed closely by teacher training programs (42 percent). Only 7 percent believed that teachers themselves should be responsible for seeking out training on learning LDs. Ainscow et al. (2020) argue that for a culture of inclusion to be successfully implemented, shared beliefs and assumptions about inclusion need to happen at the administrative level. Ainscow (2020) pointed out that education departments must be responsible for the promotion of inclusion. When administrators actively move toward supporting inclusive education, teachers are more likely to support it as well. There are numerous advantages of training implemented by a school or school district. Institutional trainings can create a cohesiveness whereby the institution and teachers can jointly work together to understand national laws and policies related to inclusion and LDs as well as effective teaching strategies and techniques. The need for institutional support was further reinforced in question 12 by some respondents who pointed out that they had not received sufficient support from their institutions.

Recommendations

- There is a clear need for more for more training on LDs for English language teachers in EFL contexts. This training might occur within the fold of trainings on inclusive pedagogies. However, specific training on LDs is also needed. Longer trainings are more likely to yield better results.

- Institutional training can help establish and reinforce relationships between institutional recourse centers and personnel and can also provide teachers with platforms for peer discussion and support. Teachers can also establish and nurture their own support systems once institutional trainings have been created.

- Teachers can set up their own Professional Learning Networks (PLNs). PLNs are social media platforms teachers use to communicate and collaborate. Through PLNs, teachers can provide support to each other and share experiences and knowledge on LDs and inclusive pedagogies.

- Connections between disability support offices and teachers are important. Disability support offices could support teachers by offering trainings on inclusive pedagogies and LDs. Disability offices should further clarify the kinds of support available within the institution to help teachers and students with LDs. Disability offices could also help teachers become aware of available resources on LDs.

- While many teachers in this study showed a preference for face-to-face trainings with an expert, in some contexts, experts might not be readily available. Institutions might need to think broadly about possible ways to approach LD training. For instance, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) with topics related to inclusion and LDs are now available—many at no cost. To create a space where teachers can discuss the content of the MOOC and share experiences and teaching strategies, institutions could set up MOOC Camps where teachers meet regularly for facilitated sessions. These sessions could be administered by school administrators, disability offices, or teachers themselves.

Limitations of the study

This study sought to find out about EFL teachers training on LDs through self-reports. What teachers report might not be an accurate reflection of their actual experiences. In this study, in particular, participants’ responses on whether they had LD training varied across questions. This could have occurred because study participants were confused about the questions or because they were hesitant to respond accurately to some questions. Additionally, while participants represented a range of countries, there were many countries that had no representation. Therefore, the responses and experiences respondents reported might not be fully representational of EFL teachers in general. Furthermore, the study only obtained data through a survey. Follow-up interviews could have provided more details regarding participants’ experience with LD training.

Conclusion

The research from this study has demonstrated that there is a need for more training on LDs amongst EFL teachers. While governments and institutions in many countries have adopted an inclusive model of education, training of teachers on inclusive pedagogies and specific training on LDs is still lacking. Laws, legislation, and policies are important, but in of themselves do not guarantee that an educational movement is successfully implemented or adequately meets the needs of the students it is intended to serve. Inclusion needs to be supported by adequate training, which should include ways to assist students with LDs. Ideally, training on inclusive pedagogies and LDs would be administered at national, district, and school levels and would adequately involve relevant stakeholders. Furthermore, teachers would adequately be supported by disability support offices within their institutions. In some schools, however, training on inclusive pedagogies and LDs might currently be inadequate or even non-existent, and robust training programs might not be initiated anytime soon—even in institutions that have adopted an inclusive model. In such cases, teachers themselves might need to seek out knowledge development on inclusive pedagogies and LDs. Teachers who currently do not have access to institutional trainings, might find their own learning opportunities by enrolling in online courses or accessing online resources or textbooks and taking part in support networks with other teachers. All English language instructors will inevitably encounter students with LDs. Teachers with the knowledge of inclusive pedagogies and specific knowledge and strategies for assisting students with LDs will be better prepared to help students with LDs successfully access the general curriculum.

References

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

Ainscow, M., Chapman, C., & Hadfield, M. (2020). Changing education systems: A research-based approach. Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273674

Al-Busaidi, S., & Tuzlukova, V. (2018). Teachers’ perceptions of practices and challenges of innovating for the inclusion of special needs university English language learners in Oman. Mağallaẗ Al-dirāsāt Al-tarbawīyyaẗ Wa-al-nafsīyyaẗ, 12(4), 659-671. http://dx.doi.org/10.24200/jeps.vol12iss4pp659-671

Alkhateeb, N. (2014). Female general education teachers' knowledge of and perceived skills related to learning disabilities in the Qassim Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Publication No. 3684747) [Doctoral dissertation, Washington State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.) What is specific learning disorder? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/specific-learning-disorder/what-is-specific-learning-disorder

Bryant, D., Bryant, B., & Smith, D. (2019). Teaching students with special needs in inclusive classrooms (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Bulat, J., Hayes, A. M., Macon, W., Ticha, R., & Abery, B. H. (2017). School and classroom disabilities inclusion guide for low-and middle-income countries. RTI Press. 10.3768/rtipress.2017.op.0031.1701

Burr, E., Hass, E., & Ferriere, K. (2015). Identifying and supporting English learners with learning disabilities: Key issues in the literature and state practice. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED558163.pdf

Cole, C., Waldron, N., & Majd, M. (2004). Academic progress of students across inclusive and traditional settings. Mental Retardation, 42(2), 136-144.

https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<136:APOSAI>2.0.CO;2

Corbett, J. (2001). Supporting inclusive education: A connective pedagogy. Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00219

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. The Macmillan Company.

Disability Rights Promotion International. (2014). Disability rights promotion international. https://drpi.research.yorku.ca/

Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L. S., & Barnes, M. A. (2007). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. Guildford Press.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(3), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173415

Haas, E. M., & Brown, J. E. (2019). Support English learners in the classroom: Best practices for distinguishing language acquisition from learning disabilities. Teachers College Press.

Halder, S. (2008). Rehabilitation of women with physical disabilities in India: A huge gap. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counseling, 14(1), 1-15.

https://doi.org/10.1375/jrc.14.1.1

Halder, S. (2009). Prospects of higher education of challenged women in India. International Journal of Inclusive Education (IJIE), 13(6), 633-646.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802094764

Halder, S., Assaf, L. C., & Keefe, M. (2017). Disability and inclusion: Current challenges. In S. Halder & L.C. Assaf (Eds.), Inclusion, disability, and culture: An ethnographic perspective traversing abilities and challenges (pp. 1-11). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55224-8_1

Hassanein, E. E. A. (2015). Inclusion, disability, and culture. Sense Publishers.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-923-4

Hittleman, D. R., & Simon, A. J. (2006). Interpreting educational research: An introduction for consumers of research. Pearson/Merrill-Prentice Hall.

Huang, Y. (2011). Developing English as a foreign language pedagogy for students with

learning disabilities in Taiwan: Insights from individual cases. (Publication No.

3488948) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison]. ProQuest

Dissertations and Theses.

Karmel, P. (1973). Schools in Australia: Report of the interim committee of the Australian Schools Commission. Canben-a: Australian Government Printers.

Kirk, S. A. (1962). Educating exceptional children. Houghton Mifflin.

Klingner, J., & Eppolito, A. (2014). English language learners: Differentiating between language acquisition and learning disabilities. Council for Exceptional Children.

Kormos, J. (2017). The second language learning process of students with specific learning disabilities. Routledge.

Kristensen, K., Omagor-Ioican, M., & Onen, N. (2003). The inclusion of learners with barriers to learning and development into ordinary school settings: The challenge of Uganda. British Journal of Special Education, 30(4), 194-201.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-3383.2003.00310.x

Lauchlan, F., & Greig, S. (2015). Educational inclusion in England: Origins, perspectives, and current directions. Support for Learning, 30(1), 70-82.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12075

Learning Disabilities Association of America. (2018). Types of learning disabilities. Learning

Disabilities Association of America

https://ldaamerica.org/types-of-learning-disabilities/.

Lemperou, L., Chostelidou, D., & Griva, E. (2011). Identifying the training needs of EFL

teachers in teaching children with dyslexia. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences,

15(1), 410-416.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.113

Mastropieri, M. A., Scruggs, T. E. (2017). The inclusive classroom: Strategies for effective differentiated instruction (6th ed.). Pearson.

National Institute for Urban School Improvement. (2000). Improving education: The promise of inclusive education. The Office of Special Education Program: US Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED441926.pdf.

Pierangelo, R., & Giuliani, G. (2010). Prevalence of learning disabilities. www.education.com/reference/article/prevalence‐ learning‐disabilities.

Polio, C., & Friedman, D. A. (2017). Understanding, evaluating, and conducting second language writing research. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315747293

Rapp, W. H., & Arndt, K. L. (2012). Teaching everyone: An introduction to inclusive education. Paul Brookes Publishing.

Reid, G. (2005). Learning styles and inclusion. Paul Chapman Publishing.

https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446212523

Singal, N. (2008). Working towards inclusion: Reflections from the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1516-1529.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.01.008

Smith, A. M. (2006). Inclusion in English language teacher training and education [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lancaster University.

Sowell, J. (2016). How to conduct an ELT workshop. English Teaching Forum, 54(3), 2-9. https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/etf_54_3_pg02-09.pdf

Sowell, J., & Sugisaki, L. (2020). An exploration of EFL teachers’ experience with learning disability training, Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 13(1), 113 – 134, https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2020.13.1.7

Thornburg, R., & Charmaz, K. (2012). Grounded theory. In S. D. Lapan (Ed.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs (pp. 41-68). Oxford University Press.

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. Adopted by the world conference on special needs education: Access and equity. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427

UNESCO. (2015). Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

Winter, E. (2006). Preparing new teachers for inclusive schools and classroom. Support for Learning, 21(2), 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9604.2006.00409.x

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf?ua=1

Zigmond, N. (2003). Where should students with disabilities receive special education services? Is one place better than another? Journal of Special Education, 37, 193-199.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669030370030901

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

Investigating EFL Instructors’ Experience with Learning Disability (LD) Training

Larry Sugisaki, US;Jimalee Sowell, US