- Home

- Various Articles - Issues

- Learning to Write by Rewriting Dominant Discourses: A De-colonial English Language Pedagogy

Learning to Write by Rewriting Dominant Discourses: A De-colonial English Language Pedagogy

Gautam Bisht is the founder of Sinchan Education and Rural Entrepreneurship Foundation. He is currently pursuing his PhD in Learning Sciences at the Northwestern University. His interests are in designing English language methods that are culturally responsive, youth development and indigenous knowledge systems. Email: gautambisht2025@u.northwestern.edu

What is culturally sustaining pedagogy?

Culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP) is a way of organizing learning such that it engages with the existing cultural practices of students. These cultural practices could by anything that the student engages in their day to day lives. Educators approach the idea of culturally sustaining pedagogy from two angles that may eventually converge. First is that schooling and learning for many marginalized cultures has been an institutional form of forgetting. Indigenous communities globally have to let go off their native culture to take up the culture of schools, and the culture of school is often a sedimentation of the values of the dominant groups. This angle looks at education politically, and thus culturally sustaining pedagogy is a way to resist the imperial tendencies implicit in education (Alim, 2017). The other approach is to look at this issue from the standpoint of learning theory. This approach proposes that learning is a socio-cultural process and it’s makes basic pedagogic sense to learn new things through that which is already known (Lee, 2003) Some other names through which something similar is proposed is culturally responsive pedagogy or decolonial pedagogy. There are way too many subtleties and nuances within and across these positions, which cannot be delved into here, but the overall unifying feature is an emphasis to engage with the cultural background of students.

Why is CSP important?

To explain the significance of this approach, let me make this a little concrete. As someone interested in the domain of language arts in India, I am faced with this intense desire amongst rural youth to learn English. In postcolonial settings, learning of English Language presents one of the most complicated double binds. The historical origins of English language education in India emerged primarily as a tool for governance (Macaulay, 1965). Almost two centuries after, language scholars argue that the colonial tendency of English language is far from over, as it continues to play a strong imperialistic role in the global south (Phillipson, 2009). There is an underlying poststructuralist view of language to this position (Becker, 1983). According to this view, language is not a neutral medium to describe an external world, but rather language constitutes the world as we understand it. Language is not a mere tool for communication, but it shapes how we look at the world and ourselves. Thus, the world of English would represent a worldview which often do not accommodate marginalized cultures in dignified ways.

On the other hand, in a caste ridden society like India, English is pitched as the only language of emancipation for the marginalized (Illame, 2020). In a society where educational opportunities were historically reserved for some; English became a tool to bypass the upper caste hegemony. The same educational reforms brought in by the British that are blamed to have caused a decline in local knowledge traditions, are celebrated by scholars that represent the marginalized caste groups. As an illustration of this, some intellectuals from the ‘Dalit’ community celebrate the birthday of Macaulay (Krishnan, 2017) English is in this context is seen the language of democracy and equality. Empirical studies have shown direct co-relation between English skills and higher wages (Bakshi, 2016). Even in popular discourse and folk wisdom, English is the language of aspiration for the marginalized. Thus, one cannot overstate the socioeconomic significance of English for marginalized communities.

With this growing demand and supply for English in the language ecosystem, there is a simultaneous decline in other languages, specifically indigenous languages. The social hierarchy of India is reflected in the hierarchy among languages, creating a feeling of inferiority in being associated with minor languages and cultures (Babu, 2015). As per a UNESCO report India has lost around 220 languages in the last 50 years and many more are labeled as endangered (Mohanty, 2020). In such a situation, English is both empowering and disempowering for learners from culturally and linguistically marginal backgrounds. This calls for a culturally sustaining English language learning framework that may work through this double bind. So, the task before us is to design an English language curriculum that (i) critically engage with the dominant worldview that comes with English (ii) critically engage with local culture itself by addressing the regressive elements in it and (iii) revitalizes and affirm which is significant in one’s own culture.

How to do CSP?

My description of the ‘how’ is not analytic, which means I will not give you some abstract stages of how this can be done. Rather I will provide you three broad elements that we arrived at in our particular situation of operationalizing CSP. During the lockdown, in September 2020, Sinchan organization started an online language learning project. The project virtually connects youth from various urban parts of the country to rural indigenous youth. Below I am providing you the details of the protype phase of our design, that was tested between October 2020- March 2021.

Element 1: Intimacy

The project involves online classes, and we all know how zoom classes have made it difficult to create an engaging learning environment. On top of this we are faced with a situation where complete strangers are connected virtually. So, the most important thing for our project was to create an intimate space. Two things in how we designed this project helped us create an intimate space. First is the small student teacher ratio. Usually, each urban volunteer is put in a group with 2 rural youth. Second thing that works to build intimacy is the fact that both urban and rural members are from the same age group. Both have their own share of apprehensions getting into this project. The urban youth have no prior training in teaching or pedagogy and is usually driven initially by a desire to bridge the skill divide between rural and urban India. The dominant intention going into the project is of ‘helping’. The rural youth also go into this project with a simple desire to learn English. Slowly this intimate space allows for sharing and personal conversations. Even though the urban -rural, teacher-student dynamics remains, we try to work out an intimate space, which is further intensified through the second element.

Element 2: Cultural sustaining curriculum

A culturally sustaining pedagogy is built on curriculum resources that often centers the culture and experiences of students. Though there can be many generative themes for a culturally sustaining curriculum, we chose the topic of food. There were three main reasons for doing so. The first reason was that some of the students had participated in a project on local food and health, and this gave them some entry point. Second, food is an everyday activity and yet encapsulates culture and identity in deep ways. Third, and by far the most important, food is a critical issue in the region from which the students come from. The district has a severe health and nutrition crisis. In such a situation local food and its role is important. What adds to the complexity of this situation is that young indigenous people, especially educated ones, are turning away from their cultural food. This is because food practices of the indigenous communities are looked down upon and are considered ‘poor’. A lot of uncultivated food items that the Santhal community forage from the forest is considered ‘uncivil’. At the level of school curriculum, chapters on nutrition and balanced diet also fail to recognize the indigenous food practices. Growing evidence suggests that supporting the consumption of uncultivated foods in rural communities could help achieve food security and nutritionally-diverse, sustainable diets. Thus, we decided to center the local food system of the Santhal community, as a cultural anchor of our pedagogy. Talking about local foods, made students the expert on the content and the urban youth the student. This reversal is significant to undercut the overarching hierarchy in their relationship.

Element 3: Multimodality and translanguaging

Indigenous communities in India, ‘suffer’ the highest educational drop out, along with other socio-economic deprivations. One key reason for school dropouts, that various researchers have pointed out is the alienating pedagogy, curriculum and disregard for indigenous languages in school setting. This results in poor learning levels of students as measured by standardized tests and eventual drop outs. Despite policy recommendations to engage with indigenous languages and cultural practices, not much has changed in the delivery of the education systems at the grassroots level. However, in last few years a fundamental development in learning has happened outside of schools, and this is mediated by the advent of the internet and cheap smart phones in rural spaces. If not children, but rural indigenous youth in the age group of 16 and above are populating the social media space. School drop outs, who struggle to read from school books, are passionately exchanging messages on Facebook. How is it that young people in rural areas who would end up struggling in standardized tests are doing pretty well in their literacy efforts in such spaces?

This is so because literacy as enacted on digital platforms like Facebook provides unforeseen affordances. Two of these core affordances are- multimodality and translanguaging. Multimodality means the usage of more than one form of expression (text, emoticons, symbols, images, animation, videos) to compose a message. This is literally every other post on social media. Translanguaging means that people often use multiple languages they know to communicate their point (Team, 2016). This is very effective as many marginal languages have been given a new lease of life due to its usage in digital mediums. Such affordances not just aid literacy development but transform the conception of literacy itself. Traditionally, and more so within educational institutions, literacy is taken to be a rigid monolingual cognitive skill to be inculcated into the ‘illiterate’ through specific drills. However, literacy in online spaces is innovative. Thus, our classes involved reading and writing in the style of the internet. Additionally, participation in digital spaces became a great point of convergence for rural and urban youth.

The recipe of CSP

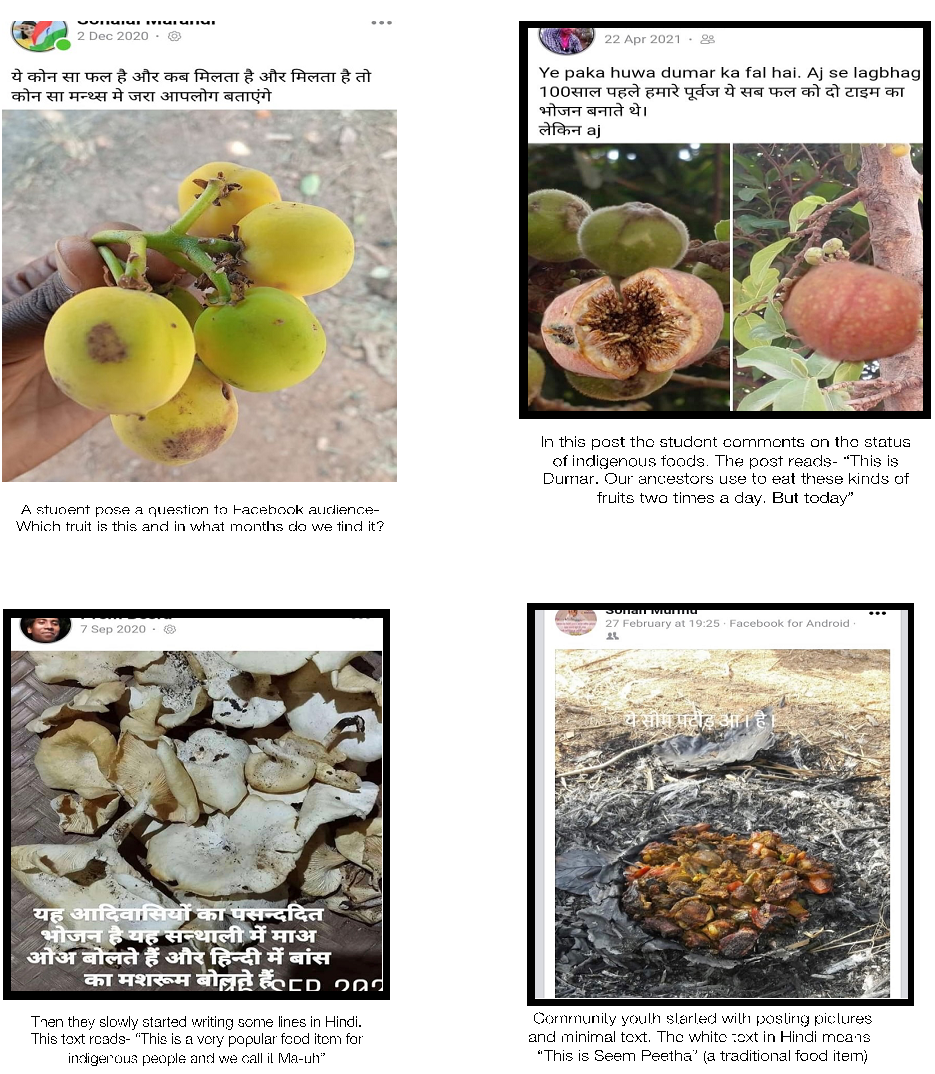

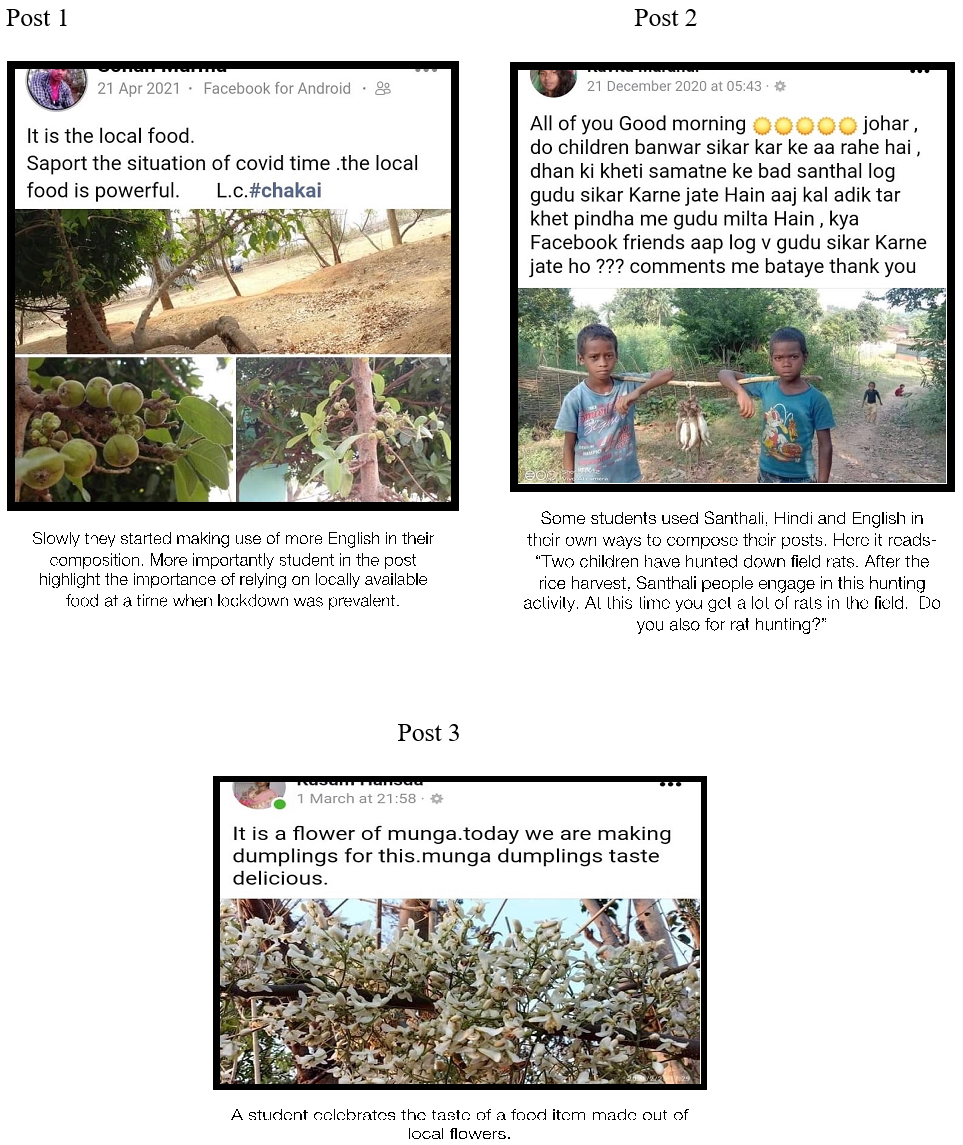

To put it all together, we had a recipe that comprised of four things: (i) aspiration of learning English, (ii) online mentors that created intimate spaces for deliberation, (iii) the theme of food systems and (iv) social media as a platform to participate in a social discourse. A very simple beginning step in the online sessions was to create a reflection on popular and unpopular foods. As prompts for discussion, they would use videos on changing food styles or read online articles that talk about declining indigenous foods. Often pictures of local food and its collection were generated by students themselves and converted into short power point tools for classes. Eventually the mentors encouraged students to make social media posts as assignments, leveraging on multimodality and the multiple languages they know. Not all students made these posts, as they still felt inhibited in using ‘wrong English’ and feeling judged by their peers online. Understanding these apprehensions, we never pushed the point of posting on social media, and kept it only as a recommendation. In the classes, students slowing started discussing about anecdotes and how their food is represented in the dominant worldview. They recounted experiences of how they had to hide their food practices from non-indigenous school friends and developed a reprehensible attitude towards it. Once the idea of telling their stories from their own vantage point emerged, students started experiment with their Facebook posts. Some of them also posted videos of their elderly and children enjoying local foods. Below I provide some examples of the Facebook posts students made in the prototype phase and how that changed over time.

What does CSP look like?

Phase 1: Students were mostly reluctant to write, so they started with just posting pictures of local food and associated practices

Phase 2: Students started writing in Hindi, the language they already knew

Phase 3: Students start using all known languages, Hindi, Santali, and English. They start writing longer text

What CSP does?

Educator John Dewey remarked the fundamental difference between ‘having to say something’ and ‘having something to say’ (Dewey, 1915). The difference is of desire. By centering a curriculum that does not speak to students and which priorities the puritan mechanics of English language, students are often placed in a position of having to say something in the class. By centering stories and voices that are often marginalized in traditional classrooms, CSP first invokes the desire to communicate. Once students have an intense desire to say something, mentors gradually help them work out the mechanics of it. But in mainstream educational settings, you can’t get away with saying that CSP enhances the desire to learn. More accepted forms to look at the efficacy of a pedagogy is to look more closely at student’s learning. This learning is often based on quantifiable parameters or a rubric. For instance, a piece of English writing is usually judged by “sentence structure”, “word choice”, “organization”, “exclusive use of target language” and “coherence”. Now if we consider some student compositions from the prototype phase against these measures, students are way off. But if our rubric includes aspects of belonging, agency, and critical thinking, can see much more in these posts. Even an early-stage composition, one can see how indigenous food systems is finding an unapologetic place in their writing. Post 2 for instance frames ‘rat hunting’ as a routine activity, centering Santhal culture and food. The student normalizes ‘rat hunting’ by asking her Facebook friends if they have ever done this, connoting the desired nature of this activity. This is very different from the usual ‘exoticized’ or ‘repulsive’ presentations which centers mainstream perspectives. Some other posts reflected on the disappearance of traditional foods, some celebrated the taste of local food, some highlighted its significance in situations when market closed down during covid and some talked about food in relation to the culture of foraging and childhood. Based on what CSP did in the prototype phase, we developed a design for the first iteration, which is currently underway. The rural youth are now trying to write a blog length multimodal piece for an online space. In this iteration we are closely looking at the development of student’s ‘voice’, ‘critical thinking’ and some conventional mechanics of their English language. Additionally, our focus is on the student teacher interaction and the teacher’s learning within CSP.

Works Cited

Alim, D. P. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies : teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. New York: Teachers College Press.

Babu, M. (2015). Breaking the Chaturvarna System of Languages. Economic and Political Weekly.

Bakshi, T. C. (2016). English language premium: Evidence from a policy experiment in India. Economics of Education Review, 1-15.

Becker, A. (1983). Toward a Post-Structuralist View of Language Learning: A Short Essay. Language Learning, 217-220.

Dewey, J. (1915). The school and society. Chicago: The University of Chicago press.

Illame, D. V. (2020). The English Language as an Instrument of Dalit Emancipation. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences.

Krishnan, M. (2017, April 1). A temple for a language. Retrieved from The Hindu: https://www.thehindu.com/books/a-temple- for-a-language/article17752224.ece

Lee, C. (2003). Toward A Framework for Culturally Responsive Design in Multimedia Computer Environments: Cultural Modeling as a Case. Mind, Culture and Activity, 42-61.

Macaulay, T. B. (1965). Minute by the Hon’ble T. B. Macaulay, dated the 2nd February 1835. Bureau of Education. Selections from Educational Records, Part I (1781-1839). National Archives of India, 107-117.

Mohanty, A. (2020). Seven decades after independence, many tribal languages in India face extinction threat. Down to Earth.

Phillipson, R. (2009). Linguistic imperialism continued. Orient Blackswan Private Ltd.

Team, E. J. (2016, July 26). What is translanguaging? Retrieved from EAL Journal: https://ealjournal.org/2016/07/26/what-is-translanguaging/

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

Do No Harm! Undesirable Consequences of Teaching about Social Justice

Mandana Arfa-Kaboodvand, EswatiniLearning to Write by Rewriting Dominant Discourses: A De-colonial English Language Pedagogy

Gautam Bisht, India