Understanding Scaffolding and Organic Mediation

Gabriel Diaz Maggioli holds a doctorate of Education from the University of Bath in the UK. He is currently the director of Ludus, the professional development and teacher research and innovation centre at the Catholic University in Uruguay. He has written over 24 books and various articles in peer-refereed and professional journals. Current professional interests include teacher learning and development within a Sociocultural perspective. Email: gdiaz@ucu.edu.uy

Introduction

Scaffolding is a ubiquitous term in language teaching. As it has been the case with many professional terms, it has slowly become part of the idiolect of language teachers thus embodying various meanings stemming from the individual understanding of the term by the teacher who uses it. In this respect, we can claim that the term scaffolding has become literalized, that is to say, it has lost – for many – its original meaning and it has been used to nominate a wide array of educational practices. These are not always in line with what the developers of the metaphor of scaffolding had in mind.

Cognizant that the words we use shape not only our discourse but the intentionality of the message we want to convey, and, given recent developments in the area of teacher education, I would like to invite readers to reflect on this powerfully ubiquitous term so as to position in its right dimension and clarify potential misunderstandings which ensue from its use.

I will start by providing a historical account of the term. Next, I will position scaffolding amongst other mediational experiences and will finish by providing a framework for identifying organic mediational episodes, those where the true spirit of scaffolding, as well as other forms of mediation, can be recognized.

A brief history of scaffolding

The term scaffolding appeared for the first time in an article on tutorial interactions written by Wood, Bruner and Ross in 1976. The article was concerned on how a tutor can support a learner in achieving success in completing learning tasks. Seen in this context – an object driven, one to one interaction, oriented at the solution of a problem – their introduction and definition of the term looks quite unambiguous. They wrote:

“[Scaffolding is] a process that enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his [sic] unassisted efforts” (Wood, et al., p. 90)

Notice that the emphasis in this definition is in assisting the learners so that a task can be accomplished with support. Ideally, that support would be phased – or discontinued – once the learner is able to operate on his/her own.

Given this widely cited definition of the term, scaffolding has come to mean anything from direct instruction, to individualized learning plans, or even, using specific tools to promote the solution of a task or problem. Notice, however, that no reference is made to the concept of learning. Hence, when we see the terms used to explain how learning happens, there is a certain epistemological dissonance, as the original definition is not concerned with learning but with problem solving.

Incidentally, in the same year as this article was published, one of its authors, Bruner (who, incidentally, is credited with coining the term), co-wrote a chapter examining the game of Peekaboo with Sherwood. In that chapter they examine how the game is played across cultures and describe the mother-child interaction as the mother scaffolding the appropriation by the child of the rules and mechanics of the game. In this sense, scaffolding is seen as the progressive and responsive bestowing of control over an activity from a more knowledgeable one to a less knowledgeable one with the purpose that the less knowledgeable one becomes able to perform the activity without support.

This second conceptualization is more akin to the concept of mediated learning. For a start, the authors do refer in this chapter to the child learning the game. Also, while the former definition saw scaffolding as a one directional intervention. In contrast, the second conceptualization sees it as an interactive endeavor during which expert and novice react to their evolving level of learning about each other, which stems from their interaction.

In trying to understand teaching and learning, the latter depiction of scaffolding as a form of mediation makes more sense than that of direct teaching. In the next section, I will explore the concept of mediation and provide a framework for assessing whether a mediational move is organic in the sense that it responds to the students’ learning needs.

Mediated Learning and Scaffolding

The notion of mediated learning stems from the work of Lev S. Vygotsky (1978; 1986; 1987; 1994). Vygotsky posited that learning involves interactions between novices and experts whereby the novice’s understanding is facilitated by the expert who uses conceptual or material tools to carry meaning across so that the novice can appropriate the social forms of regulation that bind a certain activity.

In other words, a mediated learning experience is one where a more knowledgeable other intentionally fosters the understanding of social activity and the rules that bind it for a novice who is not yet able to participate in the activities as s/he lacks the necessary self-regulation to do so in an autonomous way. Learning, according to Vygotsky progresses from an interpsychological state (where the expert mediates the understanding of the novice through purposeful interaction) to an intrapsychological state (where the less knowledgeable other has appropriated the means to self-regulate).

This interaction is oriented towards the less-knowledgeable other learning ways of self-regulation. When learning has taken place, Vygotsky claims, a Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) opens as a space where the interaction oriented at transferring control to the novice over the activity takes place. Once the novice has appropriated the mediational tools and can use them independently, we can see s/he has developed.

While Vygostky never talked of scaffolding, we can see the parallelism between Bruner’s metaphor and Vygotsky’s concept of mediation. However, for mediation to take place a certain number of conditions have to be put in place. It is to a discussion of these that I will now turn.

The Organic Mediated Experience (OME)

We say that a process is organic when it helps the individual come to full development, that is, an organic process, such as learning, should result in a definitive transformation of the subject from a lower to a higher state. In terms of learning, organic mediational experiences are those which, given the necessary conditions, result in learning that leads to development.

Diaz Maggioli (2013) cites five criteria for an organic mediational experience. Because this is an organic approach, the absence of one of these characteristics might imply that mediation is not achieved, hence, the need for all criteria to be present.

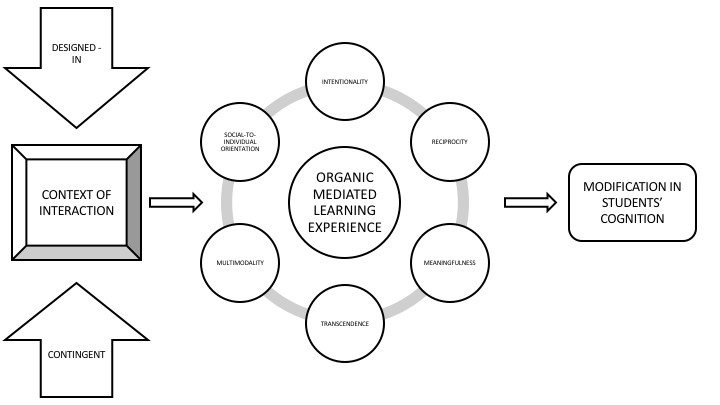

Organic mediation is the byproduct of the interplay between a designed-in level (Hammond and Gibbons, 2005; Sharpe 2006), which occurs before the actual encounter between the teacher and learners; and a contingent level, which evolves as a result of the interaction between the teacher and learners.

To Holton and Clarke (2006, p. 131), “Scaffolding anticipates some act of construction. It is not an act of closure.” At the designed-in level of scaffolding the instructor approaches the task of planning for teaching by fine tuning their instructional decision making to the level of cognitive development of learners as perceived through his or her interaction with them. This tentative representation opens up opportunities for the design of learning experiences that focus on tasks that are within the learners’ ZPD. The function of this level of scaffolding is to provide an organized sequence of work so that students can achieve specific learning goals. However, it should be noted that in planning, the teacher also has to make decisions as to how the handover of responsibility to students will be implemented, a move referred to as “fading” in the literature (Sharpe, 2006, p. 15).

Fading is important since it is the removal of the scaffold that prompts the transition from the interpsychological plane to the intrapsychological one, thus enabling self-regulation by the learners. Johnson and Golombek (2016) prefer the construct of “growth point” (McNeill, 2012, cited in Johnson and Golombek, 2016, p. 44) instead of the construct of fading, as providing evidence of learning. To them, a growth point acts as a vehicle for mediation which, when organically implemented, is conducive to learning. Because a growth point acts as a vehicle that allows thinking to be externalized while it is being shaped, and it surfaces during interaction, it can be said to attest to the fact that the mediated person has managed to appropriate the new conceptual tool and hence, mediation is no longer necessary. However, for growth points to emerge it is necessary that mediation be enacted within certain parameters.

According to Vygotsky (1986; 1978) and some of his followers (e.g. Feuerstein et al., 1980; Kozulin, 1998; Moll, 2014), an MLE possesses three criteria, which are rather self-explanatory: a) intentionality/reciprocity (active engagement by both expert and novice), b) transcendence (focus on the level of potential development) and d) meaningfulness (imbuing the interaction with meaning). Diaz Maggioli (2013) contributes two further criteria: contingent multimodality and social-to-individual orientation. By contingent multimodality he means the use of semiotic resources other than language as mediational tools. Hammond and Gibbons (2005) and Wertsch (2010) also support this view. The latter considers that semiotic tools other than language are crucial in the social and psychological development of individuals, particular in the twenty-first century when multimodality seems to be the new normal.

Finally, a social-to-individual orientation implies that culture and society act as a “generative force shaping the very nature of the human mind” (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006, p. 50). During our ontogenesis we learn and appropriate concepts already existing in our culture that are historically constructed and preserved in and through the social practices that embody them.

Conclusion

It should be evident from the discussion above that using the term scaffolding should not be taken lightly. This form of organic mediation acts as a metaphor of principled teaching that holds the potential to result in powerful learning that leads to development.

Applied to the field of language teaching, this theory holds many promises. First, it positions the teacher as a co-learner with the group that s/he teaches as s/he will have to become keenly aware of his/her students, their learning preferences, their learning needs and their approaches to learning. Secondly, it is only when the six characteristics of the organic mediational experience act in unison that learning has a chance to happen and thus, prompt development. Lastly, the role of the teacher as provider of knowledge is overshadowed by a conceptualization of the teacher as someone who mediates students’ understanding at the point of need.

Now that a theoretical framework for scaffolding and other forms of mediated learning has been clarified, we have the daunting task ahead of us to turn these theoretical inputs into pedagogical outputs that may best serve teachers and their learners. It is in this process that I am now engaged, translating theory into its practical applications.

References

Bruner, J., and Sherwoord, V. (1976). Peekaboo and the learning of rule structures. In J. Bruner, A. Jolly, and K. Sylva (Eds.). Play: Its role in development and evolution. pp. 277-287. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books.

Diaz Maggioli, G. (2013). Of metaphors and literalization: Reconceptualizing scaffolding in language teaching. Encounters/Encontres/Encuentros on Education, 14, 133—150.

Hammond, J. and Gibbons, P. (2005). Putting scaffolding to work: The contribution of scaffolding to articulating ESL education. Prospect, 20 (1), 6—30.

Holton, D. and Clarke, D. (2006). Scaffolding and metacognition. International Journal of Mathematical Education, 37 (2), 127—143.

Johnson, K.E. and Golombek, P. (2016). Mindful L2 Teacher Education: A Sociocultural Perspective on Cultivating Teachers’ Professional Development. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kaptelenin, V. and Nardi, B.A. (2006). Acting with technology: Activity theory and interaction design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sharpe, T. (2006). “Unpacking” Scaffolding: Identifying discourse and multimodal strategies that support learning. Language and Education, 20 (3), 211—231.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of Lev S. Vygotsky. Volume I: Problems of General Psychology. (Edited by Rieber, R. and Carton, A.). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1994). The problem of the environment. In R. Van Der Veer and R. Valsiner (Eds.), The Vygotsky reader. (pp. 338–354). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., and Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89-100.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Course for Teachers and School Staff at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to Motivate Your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Listening: Problems from Learners’ Perspectives

Annie McDonald, UKLearner Autonomy: Research and Practice

Jo Mynard, JapanCreating a Thinking Environment for English Language Learners

Michelle Hunter, GermanyCommunity Counts. Reflecting on the Power of Relationships, Motivation and Connection in the Classroom and Beyond

Sarah Elizabeth Sprague, BrazilHow to Teach Demotivated Students by Humanising Language Teaching

Susan Brodar, ItalyUnderstanding Scaffolding and Organic Mediation

Dr. Gabriel Díaz Maggioli, UruguayOvercoming the Speaking Headache: A Speaking Project Idea

Maria-Araxi Sachpazian, Greece