Content-based Instruction for Young Foreign Language Learning

Mija Selič is a teacher, teacher trainer and the owner of C00lSch00l private language school. She is an innovator in finding new ways of teaching and in developing teaching materials for very young language learners. She has a master’s degree in primary teaching and a degree in English. She also holds a certificate in convergent pedagogy.

Email: mija.selic@gmail.com , website: www.c00lsch00l.eu

The present article is the first in a series of articles outlining the out-of-the-box manual for teachers involved in early foreign language learning (EFLL) education that I am currently writing. The manual explains how to organise the learning process to cover language, social and communication skills using the Project-Based Approach (PBA) rather than instructing teachers how to do activities.

Twenty-first century education asks us (teachers) to focus our teaching on developing so-called twenty-first century skills: critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, communication and different fields of literacy (in short, learning autonomy). This is what modern ways of teaching suggest and apply.

Traditional manuals for teachers are most often accompanied by a fixed programme, carried out through a coursebook and/or workbook and with a set of ready-to-use materials and instructions on how to use them. The support that the manual advocates supposedly saves teachers from wasting our time creating a programme or searching for activities and making worksheets. In this way, they believe, we can focus solely on our work with children. Some coursebooks even offer us ready-to-use lesson plans.

What help is that, I wonder, when they rob us of using our intellect? No thinking is needed, just a little subject knowledge. There is no need to understand the aims, as the activities are laid out for us. No responsibility is attached, as the programme has been verified for us. All we need to do is follow what is asked of us while keeping the children amused.

Many workbooks address children the same way. There is listed vocabulary; someone has chosen it (for the children). There are pre-drawn pictures; someone has created them (for the children). There are pre-arranged units; someone has selected them (for the children). There are cut out pieces of workshop material; someone has practised fine motor skills (for the children). There are arranged questions and answers; someone has pre-planned them (for the children). All the children need to do is follow the instructions and perform some dull work, such as connecting, colouring, matching, and so on.

Again, no deep thinking needed. No discussion required. No diversity encouraged. No cooperation practised. Not enough motor and sensory skills engaged.

It is as if I had Mike do the physical training (for me), Jill work on her psychological stability (for me), Pete eat healthy food (for me), and Sally practise skiing (for me). My only job is to push myself down the hill and win the downhill race.

It doesn’t work that way, does it?

Just as sport requires one’s own effort in achieving physical and psychological fitness to win the race, teaching/learning requires one’s own (critical) thinking to be able to prepare and carry out a lesson with a useful and meaningful outcome.

We are, therefore, not only teachers but also learners for our entire life (or at least as long as we are teachers).

Traditional manuals and coursebooks encourage obedience rather than thinking (for both teachers and students). Without using our brains to exercise different opinions, to learn to accept diversity and take responsibility for our actions, we can soon end up on autopilot.

‘Modern ways of living’ can quickly push us into autopilot living. Since human beings are defined as a thinking species, we should be able to choose a different path. This is especially true of teachers; we have a unique opportunity to take a different path, if we decide to, as we work and interact with learners live, not via social media (at least most of the time).

Modern teaching/learning, therefore, does not follow instructions but instead creates an encouraging teaching/learning environment. It enables effective teaching/learning conditions, in which teachers/learners can improve in their knowledge, strategies, communication and so on by taking an active role in their own teaching/learning.

In other words, teachers/learners should be creative intellectuals who develop strategies on how to teach/learn according to our current level of knowledge.

The PBA manual, therefore, addresses teachers and learners as creative intellectuals who rely on our own minds and knowledge and seek ways to improve ourselves to be able to teach our students to rely on themselves in the same way. Thus, teachers can help students become autonomous learners as we become autonomous teachers and learners ourselves.

Developing an Autonomous Language Learner

Autonomous learners are those who know how to educate themselves without the need of assistance from a third person. They are those who can use their own thinking mind to judge what is important (for them, for the occasion, for the desired outcome, etc.), and who know how to pursue their own paths. They are the ones who doubt and ask questions in order to verify the answers, whether their own or someone else’s. They are the ones who know that nothing is fixed, or permanent, or completely true. They believe that everything is the result of one’s (personal) point of view/opinion.

Can we really say that it is possible for a young learner to be autonomous?

Our autonomy depends on many parameters: our background knowledge of the subject matter, the level of our psychological development and maturity, and also how proficient we want to become. There are some prerequisites to becoming autonomous.

When learning our mother tongue, in our first years of existence, we are thrown into life; we take in whatever surrounds us and learn through experience. We are autonomous learners then and our development depends on the ‘quality’ of our environment.

Later, when we enter an educational institution, we get assistance to deepen our knowledge systematically; our environment (the curriculum) is designed so that we can get the most out of it. At least in theory.

In practice, it is not only ‘curriculum knowledge’ that children get in school. Teachers have an important function as children’s role models; we, teachers, have an impact on building children’s confidence, motivation and socialisation just by spending time with them. And we spend a lot of time with them. More than their parents! (TA Today, Steward, Joines, 2002). It is our lifestyle, beliefs and behaviour that is subconsciously transferred to children.

As I see it, the biggest drawback in young children’s institutional education (age 5–8) is the general teaching attitude:

‘It’s too hard for them! They can’t do it!’ … searching for excuses to not try something new, something out of our established way of teaching (comfort zone).

There are certainly exceptions among teachers. Some believe in children and are open to challenges. For us, this manual can be of some assistance.

It is crucial for teachers to be open to challenges ourselves, to be independent learners; confident, mature, with high self-esteem and some knowledge of psychology. Only then are we able to give as ‘mature’ assistance as possible in raising independent students by letting THEM decide whether or not something is too challenging for them.

Children’s brains have not yet fully developed to function with their full potential, and children lack strategy. Only learning through their chance experiences, it could take years for them to gain the desired knowledge, and they may never acquire it. With the right amount of assistance from educational institutions, however, learning can be more accessible and productive.

Children’s first years of institutional learning should be focused on gaining physical and social maturity. We should provide assistance that encourages the development of the skills required (prerequisites) for children to become independent and autonomous learners (while also giving them time to discover their desired subject of interest).

We cannot ignore the fact that any assistance given is manipulation; we manipulate children to behave in a way we consider ‘proper’. There is therefore a thin line between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ manipulation, and the decision between what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’ lies in the hands of the educator.

I cannot be too wrong when I say that the majority of us were given educational assistance manipulating us to listen, obey, follow, memorise and execute without discussion. Consequently, we learned to obey authority. (Is this right or wrong?)

We were taught traditionally. And having traditional behaviour engraved in our bones, we pass on what we have learnt. I am not saying that changing our ways to become autonomous learners is easy: “… the word change is the scariest word in the English language. No one likes it, almost everyone is terrified of it, and most people, including me, will become exquisitely creative to avoid it. Our actions may be making us miserable, but the idea of doing anything differently is worse” (Emotional Blackmail, Susan Forward, PhD, 2001).

Traditional teaching

Traditional language teaching teaches the language, irrespective of the age of the learner. Since children up to the age of twelve cannot yet comprehend abstract concepts, which is what language is, all that children can take from traditional teaching is memorising isolated vocabulary, occasionally linked with some random structures that can go with particular vocabulary (I like; My favourite; I’ve got, etc.) For easier memorisation, vocabulary is presented through topics (clothes, animals, food, etc.). Even if it is gamified, the language focus is still on learning isolated vocabulary.

This is how mainstream coursebooks for YFLL are designed.

A modern approach with the PBA

In the modern approach, the target language is used for communication and thus learnt through its meaningful use.

Being introduced to a new language for the first time while also being a young learner, the PBA uses the new language to address children’s sensory, motor, social and communication skills. By using those skills, the PBA addresses strategies on how to learn language skills.

In its core, the PBA is CBI (Content-Based Instruction), only tailored to suit the young learner. For young learners, the content is the known environment (taken from a picture book story) in which children undertake gamified activities in English. In so doing, they practise their motor, sensory and social skills, through which they learn language skill strategies to communicate.

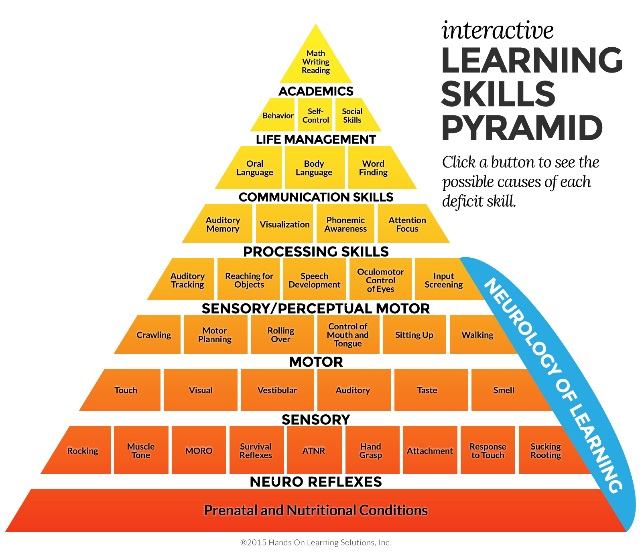

In other words, the PBA addresses the neurology of learning to build the foundations necessary for learning academic knowledge (see Fig. 1). In order to achieve this, teachers need to know the language aims, how to entwine them into the activities, and how the activities can address the neurology of learning.

HOW DO CHILDREN LEARN IN THE PBA?

Children, especially young children, deal with the world from a feeling position (TA Today, Steward, Joines, 2002). If we want them to be engaged in action, THEY need to feel good (and the teacher needs to ignore her/his reservations, should there be some).

The appropriate approach, which the traditional language approach also takes very seriously, is using games for learning.

What the traditional approach rarely considers is the children’s point-of-view, the content, and the context. In traditional teaching, children rarely experience the use of language learning; they learn merely for the sake of learning.

In the PBA, children are immersed in games and gamified activities that are based on the presented content (story). This way, all of the activities share and are embedded in the same context. All of the activities within the project work as a team; each activity has a specific aim, but at the same time all of the activities together form one complete message (project). In other words, the PBA creates language, communication and socialisation opportunities to learn.

Children use the language to be able to play (usefulness) and feel good while playing (feeling position). Usability plays a significant role in memorisation and information recall; thus, chunks, expressions and phrases become part of the children’s communication.

Gamified Activities

Children can spend the whole day playing outside, discovering, for example, the characteristics of and differences between sand, gravel and mud while building structures in a sandpit. In school, however, time is divided into lessons, and each lesson has an ‘educational’ purpose written in the curriculum. The important thing for an educator is to know how to entwine the curriculum aims into a game-like activity topped with socialisation.

Activities that have all the elements of a game, but in which the win is knowledge, are called serious games. A serious game has participants, rules, consequences if the rules are not followed, a playing time-limit, and points earned when completing a task (Gamification in Education, Kiryakova, Angelova, Yordanova). Activities that do not have all of these elements, but only some of them, are called gamified activities.

Games can offer an excellent opportunity to practise social and communication skills, while at the same time giving children a reason to use the language for playing (having fun and thus addressing the world from a ‘feeling’ position).

The quality of a serious game or gamified activity is determined by the complexity of the skills the children can use and the meaningful use of the language.

Specific elementary games consist of little or no social and communication skills; the language is focused on learning vocabulary or/and structures. They are used mainly for clarifying a specific problem (e.g., the activity ‘Can you repeat the sequence?’, described in a separate unit.)

Vocabulary repetition must be presented using a gap-fill approach (described in a separate unit), albeit a simple one (e.g., I’ve found a leaf).

Simple social games focus on exchanging information between two people (or two entities) using social and communication skills. The language is content-related but limited to the specific purpose, such as the activity ‘What are you chasing, Oliver?’ (explained in a separate unit).

Complex social games use the language for social and communication purposes, are content-related, and address the use of language appropriate for the situation. They have two or more participants or can be group work. The cooperative structure Numbered Heads Together (Kagan Cooperative Learning, Kagan and Kagan, 2009) can cover many language and curriculum aims.

Natural-like Learning

Irrespective of the method used, institutional teaching cannot be considered as a natural way of learning, because children need to be focused and prepared to learn the subject that is prepared for them at the time scheduled for them. Natural learning, on the other hand, is ‘learning-as-you-go’, using the skills and knowledge that the learner already possesses and developing them further at their own pace and time, focusing on a subject that suits the learner. Children’s natural learning is typically individual. In groups, the learning takes place through the children’s interactions, where social skills start developing.

Language instruction cannot, therefore, be ‘natural’ learning. What we can do is bring some of the natural-learning elements into the classroom and create a ‘natural-like’ environment in which children are offered an opportunity to learn.

For children to be able to learn in a ‘natural-like’ environment, they first need to learn how to focus and listen when asked to. Moreover, they need to accept their peers (because there are many children in a class and, whether they like them or not, they need to learn to tolerate them). Lastly, before the learning takes place, children need to understand and follow the arrangements that make their group function. In other words, children need to socialise in order to learn how to work in larger groups. Only then can we initiate curriculum aims and expect positive results from learning.

There is another parameter we need to consider when arranging a ‘natural-like’ environment: the learning time.

Traditionally, one lesson lasts 45 minutes. Arguments have been presented for shortening the lesson time to 20 minutes, because children’s concentration span is short. It is true that when we teach traditionally – where children are passive learners and only sit, listen and memorise – even 20 minutes is sometimes a lot.

However, modern approaches place the children in the centre of the learning process. Since their skills are still in the process of developing, children need longer to accomplish tasks (cutting, bringing, gluing, etc., even understanding). In order to make the child-centred learning process possible and effective, the time of the lessons needs to be extended to 70 or 90 minutes.

Things to remember

PBA YFLL teaching/learning places the learner in the centre of the learning process. It focuses on developing social and communication skills through projects carried out in the target language.

The teacher organises the learning process in a way that addresses children’s perception of the world, from a feeling position and addressing children’s neurology of learning.

The target language is used for communication rather than direct language learning. Thus, children learn to use the language and not only memorise it by heart.

Please check the CLIL for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creating a Motivating Environment course at Pilgrims website.

Content-based Instruction for Young Foreign Language Learning

Mija Selic, SloveniaJoining the Circles in ELT Pedagogy: Teacher Innovations in a Japanese Elementary School

Dat Bao, AustraliaPeer Interaction: Beliefs of Primary English Learners and Implications for the Classroom

Carolyn E. Leslie, Portugal