Needs Analysis: The Pillar of Syllabus Design

Shabir Hassan Banday is a professor at Moscow University for Industry and Finance, Dubai, UAE. He holds a Ph. D degree in Commerce and Management Studies from the University of Kashmir, India. He has worked as a member of Board of Academic Studies at Graduate and Post-Graduate levels. He has several books and publications to his credit.

Email: shbanday@yahoo.com

Azzeddine Bencherab is a former faculty member at the City University College of

Ajman, UAE. He has been teaching English for more than 30 years. He is author of several

articles published in international magazines and has conducted scores of workshops all over

the Gulf Region.

Email: azzeddineb@hotmail.fr

Introduction

Since it aids in determining "the gap between what the learners' actual needs are and what should be taught to them", needs analysis (NA) is, then, the foundation of any ESP course (Brindley, 1989, p. 56). In the process of creating a language, NA is crucial, and numerous academics have recognized its significance (Munby, 1978; Richterich & Chancerel, 1987; Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). According to Takaaki (2006), NA is the methodical gathering and examination of all pertinent data regarding the learners, their requirements, and their desires in relation to the specific institutions that are involved in the learning scenarios. A few of the various methods for NA will be covered in this article.

Defining needs analysis

According to Nunan (1988), NA is a series of steps used to define the parameters of a course and gather data about learners’ needs. Widdowson (1990) claims that because NA is objective, it refers to what the learners must do in order to learn the language and become, by that point, the core of the course, leading to the specification of syllabus content. Barrantes (2009) defines NA as a continuous process rather than as a set of strict rules, which implies that all of the needs identified before a particular course are likely to change during the course. Learners’ needs can be categorized in terms of:

- Necessities: Necessities refer to what learners should master as far as language is concerned to deal with a given situation.

- Lacks: Lacks refer to any existing gap between target proficiency and actual performance.

- Wants: Wants refer to want learners want or need in addition to the institution’s requirements.

The importance of needs analysis

In effect, the emphasis on learners’ needs began in the 1970s when courses were designed to accommodate individuals’ needs (Palacios Martínez 1992, p.135). Understanding the particular needs of learners may impact the course material in terms of target needs, also known as objective needs, as well as the learners’ subjective needs, or affective needs, which include their interests, desires, expectations, and preferences (Nunan 1988).

The data collected through various methods, such as surveys, questionnaires, interviews, assessments, job analyses, and observations, can serve as a solid foundation for developing a language course. Additionally, the information obtained can be utilized for evaluating and enhancing language programs, as well as for reconciling the differences between teachers' perceptions and learners’ performance (White 1998, p. 91).

Goals of needs analysis

NA in language teaching may be used for numerous and different purposes (Richards, 2009, p. 52):

- It provides a means of obtaining wider input into the content, design and implementation of a language program.

- It can be used to set objectives and contents.

- It helps determine if an existing course adequately addresses the needs of potential learners.

- It identifies if there is a gap between what learners are able to do and what they need to be able to do.

Instruments for needs analysis

There are various ways to conduct NA. According to Richards (2009), to collect data, the following instruments can be used: questionnaires, interviews, meetings, observations.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are quite interesting because they:

- are easy to prepare

- can be used for different subjects

- provide information

To obtain reliable data through questionnaires, it is essential that the language employed is appropriate for the learners’ comprehension and free from unfamiliar terminology (Yalden, 1987). The questions can be categorized as either open or closed. Open questions allow respondents to answer in their own words, while closed questions restrict the responses to predefined options. Although open questions yield a broader spectrum of information for analysts, they are often considered time-consuming for both respondents and for the subsequent analysis.

Long (2005) argues that questionnaires, when administered to a large number of respondents, not only facilitate the collection of substantial amounts of data but are also considered to be less biased compared to interviews.

Interviews

Interviews provide analysts with the opportunity to thoroughly investigate the issue at hand although they are not feasible for very large groups. Additionally, these interviews offer the benefit of capturing the respondents' answers in a recorded format. To gain a comprehensive insight into the needs of learners, analysts should avoid restricting themselves to a set list of predetermined questions (Richards, 2009).

Meetings

Meetings allow researchers to gather a significant amount of information in a brief period; however, the data collected may lack accuracy or objectivity.

Observations

Observations serve as an effective method for evaluating learners’ needs and behaviors in specific contexts. However, since many individuals feel uneasy when being observed during a task, it is essential for the observer to have the expertise to determine what and how to observe in order to gather a substantial amount of reliable data.

Having introduced possible techniques, it could be concluded that the best result will probably be generated if a combination of methods is used. In addition, before choosing a suitable method the purposes of NA should be established, as these might vary from one learner to another. (Richards 2009, p. 52).

Models of needs analysis

Numerous models of NA have been suggested by scholars. Nevertheless, the four models that analysts frequently utilize are: Target Situation Analysis (TSA), Present Situation Analysis (PSA), the Hutchinson & Waters Model, and the Dudley-Evans & St John's Model. These models have received significant acknowledgment for their ability to identify language needs from various viewpoints.

Target Situation Analysis (TSA)

The target situation refers to the context in which language learners will apply the language they are acquiring (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). This concept involves NA that emphasizes the requirements of learners upon completing a language course (Robinson, 1991). Hutchinson and Waters (1987) highlight the importance of examining the target situation through the lenses of necessities, lacks, and wants (p. 55).

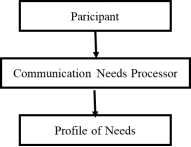

The TSA model, introduced by Munby in 1978, focuses on the communicative requirements of learners in their target context. To identify the language needs of a specific group of learners, Munby proposed a series of questions addressing various communication variables, such as topic, participants, and medium, collectively referred to as the Communication Needs Processor (CNP). The objective of Munby’s model, represented as CNP (see figure one), is to assess the extent to which learners' needs have been fulfilled by the conclusion of a language course and to evaluate their performance at the target level (as referenced in Bhatia & Bremner, 2014). This process unfolds in two phases. The initial phase of CNP involves a series of inquiries regarding essential communication variables to pinpoint the target language needs of the learners (Bhatia & Bremner, 2014). The subsequent phase utilizes the gathered data to construct a profile of the learners in relation to their specific needs.

Figure 1. Communication Needs Processor

Present Situation Analysis (PSA)

The PSA, proposed by Richterich and Chancerel (1980), can be viewed as a complementary source for TSA (Robinson, 1991). However, while TSA attempts to reveal the target needs and target level performance at the end of a language course (Songhori, 2008), PSA tries to analyze learners’ present situation and the gap between what the learners are able to do at the beginning of the course and what they need to be able to do by the end of the course in terms of language proficiency, strengths, and weaknesses (Robinson, 1991, as cited in Li, 2014, p. 1870). Questions comprised (previous learning experience, reasons for attending the course and their expectations, and attitudes towards English) in PSA determine how learners’ way of learning can be be affected by their personal background (Paltridge & Starfield, 2013).

The ultimate aim of PSA is to gather data to enhance the way a course is designed, to evaluate the teaching materials and the effectiveness of the teaching methodology at the present time in relation with the learners’ actual needs. According to Jordan (1997) and Richterich and Chancerel (1980), data collection for PSA can be obtained from three basic sources: the learners themselves, the academic institution and the prospective employer where they are required to use language.

Hutchinson and Waters' Model

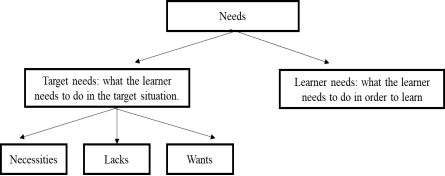

In their framework, Hutchinson and Waters (1987) delineate NA into two components: target situation needs and learning needs. The first component encompasses "necessities," "lacks," and "wants." (see figure two) "Necessities" are defined by the requirements of the target situation, representing the essential needs that allow learners to function effectively within that context. "Lacks" refer to the disparity between "necessities" and the learners’ current knowledge, reflecting their existing proficiency. "Wants," in contrast, represent the subjective needs of learners, which do not necessarily align with the objective needs identified by educators and course designers. The second component pertains to the manner in which learners acquire the language. This includes factors such as learners' motivation, preferred learning styles, available resources, the timing and location of the course, and personal characteristics of the learners. Hutchinson and Waters (1987) liken learning needs to a journey, with "lacks" serving as the starting point and "necessities" as the ultimate destination.

Figure 2. Hutchinson and Waters' Framework

As the course advances, learners' attitudes and approaches may evolve, which underscores the importance of conducting NA throughout the entire duration of the course (Richterich and Chancerel, 1987; Robinson, 1991). This means that NA should be implemented at various stages of the curriculum design process, and the identification and analysis of needs must be an ongoing endeavor (Richterich & Chancerel, 1987). Recognizing and participating in this cyclical process can assist both course designers and educators in making essential adjustments.

Dudley-Evans and St John's Model of needs analysis

Dudley-Evans and St. John, upon presenting their model, posited that NA involves determining both the "what" and the "how" of a course (1998, p.121), highlighting the significance of implementing it in a formative manner. Among the various models, their 1998 framework is regarded as the most thorough understanding of NA, as it integrates and incorporates all the previously discussed methodologies.

The primary objective of NA, regardless of the method employed by analysts, is to identify the desires and requirements of learners. By achieving this, the instructional strategies and content can be tailored to meet the learners' needs, ultimately boosting their motivation.

Conclusion

To ensure a course is effective and in alignment with the learners’ needs, it is essential to conduct a comprehensive assessment of their requirements and deficiencies before any implementation. This assessment allows educators to structure the syllabus and choose suitable materials that foster the enhancement of language skills. The significance of NA in any ESP program cannot be overstated (Munby, 1978; Hutchinson & Waters, 1987; Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001; Hamp-Lyons, 2001). In fact, performing NA prior to the course leads to a "focused course" (Dudley Evans & St John, 1998, p.121), thereby aiding in the development of course content, teaching materials, syllabus, assessments, instructional methods, and evaluation processes.

References

Barrantes, L. G. M. (2009). A brief view of the ESP approach. Universidad Nacional Costa Rica. Letras 64. Retrieved December 28, 2016 from www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/letras/article/download

Bhatia, V., & Bremner, S. (2014). The Routledge handbook of language and professional communication. Routledge.

Brindley, G. (1989). “The role of needs analysis in adult ESL programme design”. In Johnson (ed.), The second language curriculum, 63-78.

Dudley-Evans & St. John. (1998) Developments In English for Specific Purposes : A multidisciplinary Approach. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Flowerdew, J. & Peacock, M. (2001). The EAP curriculum: Issues, methods and Challenges. In J. Flowerdew, & M. Peacock, (Eds.), Research perspectives on English for Academic Purposes (pp. 8-152). Cambridge University Press.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2001). English for academic purposes. In: Carter, R. and Nunan, D. (Eds). The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages. (pp. 126-130). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hutchinson, T. & Waters, A. (1987), English for Specific Purposes. A learning-centred approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jordan, R.R. (1997). English for academic purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Long, M. H. (2000). Focus on form in task-based language teaching. In R. L. Lambert & E. Shohamy (eds.), Language policy and pedagogy (pp. 179-92). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins

Munby, J. (1978). Communicative syllabus design: A sociolinguistic model for defining the content of purpose-specific language programmes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (1988). The Learner-Centred Curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palacios Martínez, Ignacio. An Analysis and Appraisal of the English Language Teaching Situation in Spain from the Perspectives of Teachers and Learners. Ph.D dissertation. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 1992: 133-150.

Paltridge, Brian & Starfield Sue. (2013). The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes. Chichester: John Wiley & Son inc.

Richards, J.C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J.C.(2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Richterich, R. and Chancerel, J-L. 1987. Identifying the Needs of Adults Learning a Foreign Language. Oxford: Pergamon.

Richterich, R., & Chancerel, J. l. (1980). Identifying the Needs of adults learning a foreign language. Council of Europe, Pergamon Press.

Robinson, P. C. (1991). ESP today: A practitioner's guide. Prentice Hall.

Takaaki, K. (2006). Construct Validation of a General English Language Needs Analysis Instrument. Shiken: JALT Testing and Evaluation SIG Newsletter, 10(2), 1-9.

White, Ronald V. 1988. The ELT Curriculum: Design, Innovation and Management. Blackwell Publishing.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching Language as Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, Henry G. 1990. Aspects of Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Songhori, M. (2008). English for specific purposes world. Introduction to need analysis, 4, 11-15.

Yalden, J.(1987) Principle of Course Design for Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

Needs Analysis: The Pillar of Syllabus Design

Azzeddine Bencherab and Shabir Hassan Banday, UAE