- Home

- Various Articles - Story telling

- Story, Story, Tell Us a Story: Storytelling in Language Teaching and Learning

Story, Story, Tell Us a Story: Storytelling in Language Teaching and Learning

Vera Cabrera Duarte holds a post-doctorate degree in Interdisciplinary Studies, Ph. D and master’s degree in Educational Psychology. She is a professor at the College of Philosophy, Communication, Languages and Arts of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo. She has been carrying out a research project entitled Living Drama in the Classroom: a proposal for Significant Learning. Email: veracabrera@livingdrama.com.br

Elizabeth M. Pow has taught on graduate and undergraduate programmes at Faculdade São Bernardo do Campo and Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Brazil. She holds an M.A. in Applied Linguistics. Her research interests are Phonology, Teacher Education and Teaching Materials Writing. E-mail: elizabethpowelt@gmail.com

Maria Aparecida Caltabiano is a Professor at Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP), Brazil. She holds a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics, and her area of research are Linguistics/Applied Linguistics, with emphasis on teacher and translator training, multilingualism and bilingual education, use of technology in education, and analysis of language in different contexts. E-mail: cidacalt@pucsp.br

Note

This article was originally published in Torresan, Paolo; Peruta, Vanessa Della (Org.). Ensino de línguas. Caminhos para a formação docente. 1ª.ed. São Carlos: Pedro & João Editores, 2025, v. 1, p. 243-269.

“Everyone has a story to tell as we are instinctively born with the ability to tell stories. Since stories can touch students’ hearts before their minds, they are recognized as deeply appealing and motivating. The process of building stories in the mind is a meaning-making process.”

David Heathfield, 2023

Introduction

It is widely known that storytelling, or the art of telling stories, has been present in language teaching for many years, regardless of the pedagogical approach recommended at the time. More recently, storytelling has also played a role in the fields of psychology, communication, and the arts, such as cinema, drama, literature, and marketing. Thus, storytelling fosters a significant interdisciplinary field for research and classroom practice. Our article will delve into this area, connecting it to educational psychology and language teaching, especially to the affective aspects of an additional language teaching-learning.

In our case, as experienced teachers, and our colleagues, we certainly agree on the enormous potential of this practice to create an engaging and meaningful learning environment for students, even though they are immersed in the digital world, surrounded by media. When encouraged and involved in their own narratives, while reflecting on themselves and their own experiences, learners tend to use the language they are learning more naturally, thus arousing interest in their peers and in the audience at different events.

In terms of language acquisition, the use of storytelling involves oral production and comprehension, vocabulary, colloquial expressions, grammatical structures, pronunciation, intonation, among other aspects, which we will discuss in this article.

From a cross-cultural perspective, storytelling provides knowledge of and engagement with what is different, with what is ‘foreign´, with what surprises us in other cultures, or in other environments. By sharing diverse cultural elements, typical of people, a community, or a family, we can get to know one another better and develop empathy and solidarity with other people.

Our focus will be on English language teaching and learning in higher education, but the ideas discussed here can be applied to a variety of educational contexts, including early childhood education and languages in general (German, Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, etc.) as first and second languages. Because telling stories has shown to be such an effective practice, it has been a recurring theme and the subject of plenty of research in teaching and learning additional languages.

In our review of the literature for this article, we found a variety of perspectives on storytelling. Research can include procedures for the teacher as storyteller, as in Cameron's work (2001), aimed at teaching languages to children between 5 and 12, and in Dujmović's article (2006). In works such as those by Dilli Nunes and Morelo (2019), the focus is on the role of the student as storyteller, in this case in a course of Portuguese as an additional language for foreigners. This perspective converges with ours.

Historically, authors such as Hill (1965), Byrne (1970), Byrne & Wright (1974); Underwood (1976), Kleber (1988), Wright (1995), were well known to English language teaching in the 1970s to 1990s, proposing the use of storytelling in teaching practices for oral comprehension and expression. The titles of the works - Advanced stories for reproduction; What do you think? Pictures for Free Oral Expression; What a Story! Listening Comprehension - reflect the focus on teaching at various times: stories for reproduction, production and listening.

In the last decades, Duarte (1996, 2015), Heathfield (2015, 2017, 2023) and others have worked with storytelling as a teaching activity and as an object of research which, in some ways, can bring forth a complementary perspective. By prioritizing elements such as affection, empathy, and cultural aspects such as folklore, legends and tales, stories can unite people from all over the world. Heathfield (2023), introducing his Creative and Engaging Storytelling for Teachers (CrEST) course, says: “It´s hard to express the sheer joy of a CrEST course. The course feels like an intercultural coming together of hearts and minds, a celebration beyond borders, a free and creative sharing of wit and wisdom from around the world.”

The article is organised into four parts: first, we will review the use of storytelling in different periods and studies, including relevant authors in the field. Secondly, we will discuss project-based learning, followed by a report on successful experiences at two private universities in São Paulo, within the Storytelling: Engaging and Learning Project, which is part of a wider research project called ‘Living Drama and an interdisciplinary look at English language teaching and learning contexts: theatre activities in focus’. We will conclude by pointing out ways to promote the implementation of storytelling in undergraduate courses and in extension projects, as language, art and interdisciplinarity are essential themes for our future teachers today.

Time tunnel: storytelling in textbooks and classroom practices

As a human activity, storytelling is known to be as old as the use of fire, and it is through stories that the past can be linked to the present and bridge the gap to the future.

In language teaching, we could say that stories have been dealt with in several ways; initially, they appear in short texts in textbooks for the learning of the target language, specifically designed to teach grammatical items, vocabulary, and certain language structures. In coursebooks grounded on methods such as grammar and translation and the direct method, for example, stories tend to be merely a pretext for describing images or situations, for presenting and illustrating a specific grammatical item, as already mentioned.

Simplified stories in teaching materials can also be adaptations of works of literature and are intended for comprehension practice, with interpretation questions or to be translated, depending on the method. On the other hand, textbooks began to include stilted texts, in which there was only the practice of replacing narrative elements to make up a "new" one or retelling the story.

Stories also appear in publications aimed specifically at practicing different skills, as can be seen from the titles mentioned above: Advanced stories for reproduction; Pictures for free oral expression. Hill (1965) provides short stories with pictures in his more advanced work. The Introduction suggests procedures for using them: Listening and Speaking, Listening and Writing, Reading and Writing. Students listen to a story read by the teacher and then reproduce it orally or in writing or, if working on their own, they can read it, close the book, and then write down the text from memory. By the same author, in Volume I Elementary, we find a short case, followed by comprehension questions easily found in the text; then, a proposal to write a half-finished story related to the initial text, in which learners are only asked to fill in the blanks with a word (Write this story. Put one word in each empty place. You will find all the correct words in the story on page 4).

Another aim of oral and written production activities was to practice verb tenses in the past or connectives, with expressions such as then, after that, once upon a time, one day, when I was a child - typical of narratives. However, in the daily, natural use of language, we see that stories are also told in the present tense. Therefore, the use of stories as a pedagogical resource was initially conditioned to the teaching of structure and vocabulary, an influence of the structuralist perspective of the time in different fields of education and language teaching.

With the communicative approach in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the focus shifted from the system and structure of language, lexicon, and grammatical rules to meaning and communication. For Canale and Swain (1980) and various other researchers discussing the communicative language movement at that time, there should be a combination of emphasis on grammatical correctness and meaningful communication.

According to Leffa (2012):

'It was discovered that people did not learn languages to pronounce syntactically correct sentences without an accent, but to achieve practical goals aimed at specific outcomes, such as understanding an instruction manual, interacting properly with a customer, or obtaining information about a product. The lexicon and syntax of a language exist not only to express notions of time and space, to represent the reality that surrounds us, but also to transform that reality. A simple sentence like 'I'm tired' can be uttered not only to reveal tiredness, but also to justify a mistake made, to decline an invitation to dinner, or to tell someone that you want to leave the party and go home (p. 397).

Teaching materials are clearly beginning to reflect this change, as can be seen from the titles of publications from the 1980s. Books such as Klippel's (1984) Keep talking. Communicative Fluency Activities for Language Teaching and Klebber (1988) - Build your case: Developing Listening, Thinking, and Speaking Skills in English provide plenty of suggestions for working with students, focusing on fluency and oral communication (listening, thinking, speaking).

In the guidelines for using the proposed activities, Klippel (1984, p. 4) makes an important observation that reminds us of one of the communication processes mentioned by Morrow (1981) when discussing the communicative approach, namely the information gap. In real communication, when a question is asked, one of the participants may not know something that the other knows. Klippel makes two suggestions in this respect: teachers should work with activities where there is an information gap and an opinion gap. Information gap activities lead participants to exchange information to find a solution (e.g., rewriting a text, summarizing, solving a problem). Opinion gap activities involve texts with controversial ideas that lead students to defend their points of view. This category includes activities in which participants share feelings about common experiences. Such activities include storytelling.

There is an information gap in the suggestions made by Klippel (1984, p. 130), even though some of them are pre-defined. They can be done in pairs, individually or in groups, real or imaginary. For example, the teacher brings pictures cut out from newspapers, and in groups students have to write a newspaper report; the teacher hands out papers with the beginning of a sentence (When I was a little boy/girl...; I used to have/ I would like to have...) and the students are to continue; and similarly, the teacher hands out papers with a noun, a verb and an adjective on them to all the students, and starts a 'story', while the students have to continue it using the pre-selected words (chain story). Looking at Klippel’s (1984) suggestions, we can see that some of them are certainly still used in language teaching today.

But there are other factors to consider. Talking about oneself, even for experts, as Klippel (1984, p. 6) remarks, is not easy; if the environment is unfriendly or hostile, the learner will fear being ridiculed. So, the teacher's role is essential in creating a calm and friendly atmosphere, as students will tell others about their feelings and preferences. These observations are in line with authors such as Moskowitz (1978), Krashen (1982), Oxford (1991) and Arnold (1999) who are concerned with care, affect, fear and empathy. Again, the titles of the works reflect the focus of their research: Caring and sharing in the foreign language classroom, Dealing with anxiety, Affect in language learning.

This perspective has been influenced by humanistic psychology in education. We remember the work of Carl Rogers, the creator of the person-centered approach, especially the concept and relevance of meaningful learning (1985). The student is considered the center of the teaching-learning process, and a more humanistic view tends to prevail, with special emphasis on the affective component of the teaching-learning process. A global rather than a fragmented view of the human being is favored, and in the classroom, this global perspective seeks to recover emotions, feelings and, consequently, to enrich interpersonal relationships (Rogers, 1959; 1985; Duarte, 2004, p. 125).

But what is meaningful learning from Carl Rogers' perspective and how does it relate to storytelling? We highlight four of the ten basic principles of meaningful learning presented by Mahoney (1976), quoted in Duarte (1996). They are:

1. Every student has the potential to learn and tends to fulfill their potential. Learning is inherent to human beings, as it involves an inner capacity for realization.

2. Every pupil has an 'organismic capacity to appreciate'. In other words, they can evaluate, in all their human dimensions, the choices to make, based on the satisfactions and dissatisfactions of their experiences.

3. Every student shows resistance to meaningful learning. Such resistance indicates a regulatory defense mechanism inherent to human beings and represents the body's reaction to change, as meaningful learning will necessarily imply transformation. Therefore, it is understood that by reducing threat, resistance tends to be reduced.

4. When the learner's resistance to meaningful learning is low, they are more likely to fulfill their potential to learn.

In this way, the relationship between meaningful learning and storytelling, as presented here, comes about because the didactic proposal underlying the projects is based on an environment which can favour openness to learning. Such an environment can occur where empathy and respect for differences are key, that is, when the learner´s personal goals are considered, by valuing their historical moment, which is determined by a socio-economic, political, cultural and religious context (Duarte, 2002, p. 38).

Project-based learning: why projects?

As we have said, storytelling is not a recent activity, but its practice has changed over the years. Whereas in the past language teaching focused on the language system, the teacher's methodology and the student's passive attitude, in recent years, especially with the growing use of digital information and communication technologies in teaching, the focus has shifted to the student and their learning. Not the student in isolation, but in their family and social context, communicating with peers, the group and the world.

In this sense, we resort to the words of Valente (2014) when referring to changes in higher education: 'As for the classroom, it will have to be rethought in its structure as well as in the pedagogical approach used' (p. 81). To cater for this 'new' student, academics have been working with active methodologies, including Project Based Learning.

In Caltabiano and Duarte (2023), we reported on the successful experiences we have had in two undergraduate courses at our university: Portuguese/English Languages and Literatures, and English/Portuguese Translation. In that work, students have developed projects focusing on interdisciplinarity, languages, linguistic-cultural diversity, and human rights.

Once again, we bring in Valente (2017), who states:

Active methodologies are understood as alternative pedagogical practices to traditional teaching. Rather than teaching based on information transmission, on rote learning, as criticized by Paulo Freire (1970), in active methodology the student will take a more participative stance, solving problems, developing projects, thus creating opportunities for the construction of knowledge. (p. 78)

As pedagogical practice, storytelling continues today, not as an isolated activity for developing spoken production, but as part of a project requiring different procedures. Students, seen as the protagonists, will research, find information, work in groups, share their work, make decisions, under the teacher's guidance; there is planning that involves a lot of individual and collaborative work, especially as their creations will be made available in the language they are learning.

However, for students to have the theoretical background for their projects, there is still a way to go: they need to know the additional language and know what and how to speak. Besides, students also learn about narrative structure and prosody (intonation, pauses, pronunciation, rhythm).

Before sharing our experiences, let us take up the words of Celani (1996), quoted in Cysne, Soares and Duarte (2007):

I see the language teacher as someone involved in a process of development arising from the need to satisfy inner demands, a process that Barnett (1994) calls becoming, which leads to the construction of the self through critical dialogue and mutual reflection, with colleagues, in a learning community in which the group finds its own dynamics, making use of unconstraining models and frameworks (Celani, 1996).

Let us now look at how the projects were carried out at the two participating universities, culminating in the Storytelling Corner: Joint Events that contributed to the development of a learning community. Firstly, we will present the route guide that paved the way to preparing the stories that were shared in four meetings. Next, we will describe the organization and implementation of the project.

Storytelling: project-based learning experiences - teachers' views

As already mentioned, storytelling is one of the oral production practices in language teaching in the context of the Portuguese and English course. However, it is not an isolated practice, but part of yearly projects. Storytelling: Engaging and Learning was a project carried out over four semesters (2021-2022), in which students of Portuguese and English language/literature courses in two private institutions in São Paulo shared their stories in four meetings per semester. The subjects in the curriculum were English Language: Oral Narratives and the Classroom and English Language: Oral Practice Workshop. As such subjects are taught at the beginning of the undergraduate course, students may sometimes feel uneasy because they are experiencing a new stage of life, that of university. At the same time, certain demands of the subjects make it difficult for some students to communicate orally in English. Therefore, the project aims to encourage the desired engagement and confidence in students by sharing experiences, ideas, values, and visions, and by exploring the potential of narrative and storytelling in learning and improving English.

The guide...

To make our planning clearer, here is a guide drawn on the projects we have implemented, and which accompanies us whenever we start a class. The steps presented on the table below can be adapted to each teacher's context. There are targeted questions to help develop the stories and tips/reminders to get students to perform more confidently when telling their stories.

Chart 1. Route guide to storytelling

|

1. Warm-up activity

|

Is storytelling fun? What is your experience? Have you ever been told stories? What kind of stories do you remember listening to? Who told you stories? Tell us a little about this person: name, relationship, or friendship. |

|

2. How is a story structured?

|

Stories are an important part of our daily lives. They have a beginning, a middle, and an end. a) How does the story start? Where does it take place? Who are the characters? What essential information sets the mood? b) How does the story develop? What is the main event that causes a conflict in the story? When exactly does the conflict arise? What tension, suspense and emotions does the conflict unleash? c) How does the story end? How is the climax revealed? How is the tension released? How is the conflict resolved? What decisions do the characters make? What secrets are revealed and what secrets remain? How do the facts fit together? What feelings are expressed (empathy, love, pity, disappointment, betrayal, deception)? |

|

3. Building stories. Themes. |

Personal stories, folk tales, fairy tales, legends, ancestral tales, etc. |

|

4. Linguistic aspects

|

|

|

Prosody and pronunciation |

Pay attention to the pronunciation of ed endings (/t/ /d/ /id/) in regular verbs and adjectives, and irregular verbs in the simple past and past perfect tense. |

|

Grammar. Stories. |

The sequence of events is the order in which they occur in the story. It is important that they occur in clear order so that they make sense to the reader and listener. Generally (but not always) stories are told in the past tense because they describe past events, such as personal accounts. Avoid mixing the present and the past when talking about past events. This can confuse the reader or listener as to when the event took place. |

|

Verb Tenses and Adverbs of time |

Past simple - We left on a rainy day. Past continuous - It was pouring down at midday. Past perfect - It had rained off and on for ten days when we arrived there. Past simple + past perfect - When we got there, they had already left. Past perfect continuous - We had been waiting to escape for what seemed to us ages and ages. Expressions of time - last week, the day before yesterday, last month, in 2020, three weeks ago, all of a sudden, suddenly, out of the blue, in a nick of time. |

|

. Telling stories is different from reading stories. So, remember: . Write your stories and then get ready to TELL your story. . Use mind maps, draw your stories, use keywords, make an outline to remember your story. . Practice, record, rehearse, work in pairs, work in groups - these are all essential elements for improvement. . Pauses, eye contact, interactions, and body language are essential in storytelling. |

Final product: Storytelling Corner 1, 2, 3, 4

Storytelling Corner: Joint Events were the online meetings held in 2021-2022 via Zoom platform, where the students told their stories to teachers, classmates, and friends from both institutions. They were organised as follows: the teachers first presented the activity, explaining its objectives and theoretical background; then the students presented their stories, while the guests had the task of commenting on the content, organization and form of communication chosen by the presenter. The days leading up to the presentations were busy with rehearsals, individual and group tutorials with the students, which were productive learning moments.

The activities carried out by university 1 were personal stories linked to objects that were meaningful to the students or memories of unforgettable scenes that served as a means of illustration and inspiration. For example, L. presented her 'precious treasure', which she called 'my precious box', and her story was about each object that she carefully took out of the box. Another student recalled her first day at university and told us how she overcame the fear and embarrassment of starting university. Sharing personal stories created such a powerful sharing of experiences that it helped promote an environment of meaningful learning, as one student said: ´I found it very interesting to hear about the storyteller present in each person's life, and I learned that sharing stories brings us closer to those who tell them´.

The words of one of the students at the end of the storytelling session reveal joy, pleasure and gratitude: …’ to be there, to look and tell how important that hammer and that key-ring are to me...to revisit my past and to realize how much my life has changed and how much those objects have also changed who I was meant to be who I am today...to be able to say what they mean to me was a big challenge. But I confess that nervousness is no match for the feeling of nostalgia, and the joy I feel at being who I am... Thank you so much for everything. Another student highlights the importance of listening to her colleagues during her storytelling: ...It was even more interesting to present and interact with people. When they asked questions and made comments, I felt that people were also open to listening to me and being receptive to the stories I was telling.’

Sharing memories is rarely seen as a common practice in the classroom, but as the participants pointed out, it can have a role to play in interpersonal relationships as it involves sharing experiences, ideas, and feelings. Students get to know one another; they may be more open to new relationships while developing empathy in the learning process.

To celebrate the centenary of Modern Art Week, an arts and cultural movement linked to Brazilian identity, University 2 encouraged the creation of stories about diversity and identity in a session entitled 'This is who I am'. Students shared stories about their Indigenous, African, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish ancestors, as well as their trials and tribulations. In preparation, the students had weekly meetings over four semesters to share, plan and record their ideas. By working in small groups, they wrote their stories in both languages and presented them to the participants at the event. At the end of the project, in a meeting with the students to reflect on and assess the process, the development of English language skills was highlighted: oral production and creative writing, collaborative work, planning the stages of the project, familiarization with specific literature, the use of technological resources, as well as the exploration of other professional areas where storytelling is used.

According to one student: 'Telling my story - with imperfections in both languages - made me appreciate who I am and my roots'. Another student, enthusiastic about the project, spontaneously created a narrative in English and Portuguese, linking all the testimonies of his classmates and proposing a conclusion.

The practice of oral narratives, the creation of a website to publish those recorded stories and the proposal of an extension course on storytelling were some of the paths taken by the students from both institutions. Feedback from the students showed a gradual change: greater self-confidence and development of their communicative skills in English.

On assessing the project, from its design, preparation, and implementation through meetings, we believe the objectives were achieved. Feedback reports by the students from Institution 2 stress a few positive points: the students were able to create personal stories of becoming more competent in the English language, while building an environment that promoted a sense of belonging to the group; favoring the development of autonomy and authenticity of action, as behavior that is intrinsically motivated and directed by personal choices rather than by impositions. Our idea was that the proposal should arouse attention and adherence to the desire to know. We envisaged the Storytelling project as an opportunity for meaningful learning in Rogers´s perspective (1985), and that is what happened.

This collaborative project was the result of actions that allowed our students to choose their objectives, their pace and the content shared in presenting their stories. As educators, we encouraged them to act spontaneously, based on their choices and according to their English language proficiency. We share our experience here as an example of what can be done with storytelling in a project. These are ideas that can be adapted by the teacher according to their context, as we do with each new class.

Talking to future teachers

What can we suggest to future teachers and colleagues? For those studying English in a country like Brazil, with few opportunities for real interaction, it is essential to set out spaces where students can experience real communicative situations and, as in our proposal, get them to talk about and listen to situations that affect them personally.

As teacher educators, we are aware that our future teachers currently have countless resources at their disposal through digital platforms to autonomously develop their knowledge, linguistic-discursive competence and fluency in English. However, we also know that the personal contact that takes place in and through storytelling, based on revisiting lived experiences and empathetic listening in a classroom situation, shows how important affect can be in the teaching-learning process.

Two institutions, two different and formative disciplines with common objectives: English language learning, and the aim of contributing to learners´ holistic development in its intellectual, emotional, and cultural dimensions. Taking up Celani (1996), our activities sought to fulfill inner energies in the search for self-construction through critical dialogue and mutual reflection, by creating a learning community in which students felt welcome in their attempts to take risks. Additional language teaching can play a key role in terms of fostering cooperation and empathy. As teachers we want our students to be sensitive to the feelings of others, and assessment of the project shows this happened. More than a language learning initiative, we see a wider scope of storytelling in extension activities that can strengthen the links between university and community.

References

Arnold, J. (2005) Affect in Language Learning. Fourth. Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [1999].

Barnett, R. (1994) The Limits of Competence, Knowledge, Higher Education and Society. Buckingham: SRHE and The Open University Press.

Byrne, D. (1970) Intermediate Comprehension Passages. With recall exercises and aural comprehension texts. London: Longman.

Byrne, D.; Wright, A. (1974) What Do You Think? Pictures for Free Oral Expression. London: Longman.

Caltabiano, M. A.; Duarte, V. C. (2025). Aprendizagem baseada em projetos: o aluno como protagonista. In: Vallejo, Almudena Santaella. (Org.). Experiencias de innovación educativa aplicada a la formación del profesorado. 1ª. ed. Madrid: Editorial Dykinson, S.L., v. 1, p. 31-41.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Canale, M.; Swan, M. (1980) Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1 (1), p. 1-47.

Celani, M. A. A. (1996) O perfil do educador do ensino de línguas: O que muda? Mesa-redonda do 1º Encontro Nacional de Política de Ensino de Línguas – I ENPLE. Florianópolis, SC.

Cysne, A. E. M.; Soares, M. F.; Duarte, V. C. (2007) Aprendizagem de língua inglesa na universidade. Claritas, 13, p. 83-99.

Dilli Nunes, C.; Morelo, B. A.(2019) Contação de histórias no ensino de gêneros orais em Português como Língua Adicional. Orientes do Português, vol. 1, p. 91-102. https://doi.org/10.21747/27073130/ori1a9

Duarte, V. C. Aprendendo a aprender. Experienciar, refletir e transformar. Um processo sem fim. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. Tese de doutorado, 1996.

Duarte, V. C. Transformando Doras em Carmosinas: uma tentativa bem-sucedida. (2002). In: Celani, M. A. A. (org.) Professores e formadores em mudança. Relato de um processo de reflexão e transformação da prática docente. Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras, p. 37-54.

Duarte, V. C. (2004) Relações interpessoais: professor e aluno em cena. Psicologia da Educação, 19, , p. 119-142. https://revistas.pucsp.br/psicoeduca/article/view/43348

Duarte, V. C. (2015) Teaching/Learning English as a foreign language: overcoming resistance through drama activities. Third 21st CAF Conference at Harvard, in Boston, USA. Conference Proceedings vol. 6, n.1. ISSN 2330-1236.

Dujmović, M. (2006) Storytelling as a method of EFL teaching. https://hrcak.srce.hr/11514

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Heathfield, D. (2015) Storytelling with our students. Techniques for telling tales from around the world. Peaslake: Delta.

Heathfield, D. (2017) Spontaneous speaking: Drama activities for confidence and fluency. Peaslake: Delta.

Heathfield, D. (2023) Let me tell you a story you haven´t heard before: Setting up global online storytelling courses and coaching. Humanising Language Teaching Journal. https://www.hltmag.co.uk/oct23/let-me-tell-you-a-story

Hill, L. A. (1965) Elementary Stories for reproduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hill, L. A. (1965) Advanced stories for reproduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kleber, R. E. (1988) Build your case: Developing listening, thinking, and speaking skills in English. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Klippel F. (1984) Keep talking. Communicative fluency activities for language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krashen, S. D. (1982) Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Leffa, V. J. (2012) Ensino de línguas: passado, presente e futuro. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, vol. 20, n.2, p. 389-411, julho/dez.

Mahoney, A. A. (1976) Análise lógico -formal da teoria da aprendizagem de Carl Rogers. Tese de Doutorado, PUC-SP.

Morrow, K. (1981) Principles of communicative methodology. In Johnson, K. and Morrow, K. (Eds.) Communication in the classroom. Applications and methods for a communicative approach. London: Longman.

Moskowitz, G. (1978) Caring and sharing in the foreign language class. New York: Newbury House.

Oxford, R. (1991) Dealing with anxiety: some practical activities for language learners and teacher trainers. In: Horwitz, E. K. & Dolly, J. (eds.) Language anxiety from theory and research to classroom implications. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rogers, C. (1959) A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships as developed in client-centered framework. In: Kock, S. (ed.). Psychology of Science, vol. 3, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, C. (1985) Liberdade para aprender em nossa década. Tradução de José Octávio de Aguiar Abreu. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas.

Underwood, M. (1976) What a story! Listening Comprehension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Valente, J. A. (2014) Blended learning e as mudanças no ensino superior: a proposta da sala de aula invertida. Educar em revista, número especial 4. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.38645

Valente, J. A. (2017) A sala de aula invertida e a possibilidade do ensino personalizado: uma experiência com a graduação em midialogia. In: Bacich, L.; Moran, J. (orgs.) Metodologias ativas para uma educação inovadora: uma abordagem teórico-prática. Porto Alegre: Penso.

Wright, A. (1995) Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

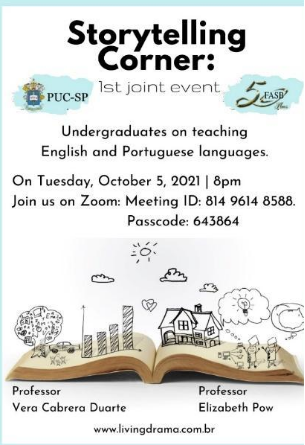

The event poster

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

Story, Story, Tell Us a Story: Storytelling in Language Teaching and Learning

Vera Cabrera Duarte, Brazil;Elizabeth M. Pow, Brazil;Maria Aparecida Caltabiano, Brazil