- Home

- Various Articles - Technology

- Taiwanese Freshmen’s Preferences and the Effects on Vocabulary Acquisition of Online Annotation for Reading an Extended Text

Taiwanese Freshmen’s Preferences and the Effects on Vocabulary Acquisition of Online Annotation for Reading an Extended Text

Chin-Wen Chien received her Doctor of Education degree from the University of Washington (Seattle, USA). She is a professor in Department of English Instruction of National Tsing Hu University in Taiwan. Her research interests include language education, language teacher education, and curriculum and instruction. Email: chinwenc@ms24.hinet.net

Introduction

When reading texts, individuals often encounter unfamiliar or challenging vocabulary. In response, some readers may choose to consult traditional or online dictionaries, while others may rely on annotations—defined as “an explanatory note, or body of notes added to a text, especially with regard to literary work” (Wolfe, 2002, p. 491). For language learners in particular, multimedia annotations or glosses offer notable benefits. These include enhanced reading comprehension, improved vocabulary acquisition, and support for diverse learning preferences and needs. Moreover, such annotations facilitate access to and engagement with authentic texts, making them a valuable pedagogical tool in language learning contexts (Boers et al., 2017; Zhang & Zou, 2020; Zou & Teng, 2023).

Recent empirical research on annotations primarily examines the impact of different annotation types and their spatial placement on vocabulary acquisition among English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners (Boer et al., 2017; Papin & Kaplan-Rakowski, 2024; Yeh & Wang, 2003; Zhang & Zou, 2020; Zou & Teng, 2023). While several studies have investigated the role of video-based annotations in enhancing both vocabulary acquisition and listening comprehension (Chen et al., 2022), others have focused on the relationship between annotations and learners’ vocabulary development in conjunction with reading comprehension (Boer et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2022; Zhang & Zou, 2020; Zou & Teng, 2023).

Nation (2001) identifies three dimensions of word knowledge: form, meaning, and use. Despite the growing interest in multimedia annotations for language learning, existing research has largely overlooked how these dimensions of word knowledge are represented in online annotation tools. Specifically, few, if any, studies have examined the types of word knowledge that such tools provide. This study seeks to address this gap by investigating the word knowledge components embedded in three online annotation tools, as well as exploring first-year university students’ preferences and vocabulary learning experiences with these tools. From a pedagogical standpoint, the findings aim to inform curriculum design by offering insights into how multimedia annotations can be effectively integrated to support EFL learners’ vocabulary development.

Three online annotation tools—Lingro, VocaGrabber, and WordSift—were introduced to 26 first-year university students enrolled in a freshman English course at a university in northern Taiwan. This study addressed the following research questions. First, what types of word knowledge are provided by these three online annotation tools? Secondly, in what ways do these tools support vocabulary learning? Thirdly, what challenges do freshmen encounter when using online annotation tools for vocabulary acquisition? Based on the findings, the study offers practical suggestions for designing and selecting effective multimedia annotations to enhance vocabulary learning in EFL contexts.

Literature review

This section reviews literature in three key areas: definitions of annotation, the benefits of annotations in relation to word knowledge, and a comparison of empirical studies on the effects of annotations on learners’ vocabulary acquisition. Following this review, the research gap will be identified, and the conceptual framework for the study will be presented.

An annotation, or gloss, refers to the practice of adding comments or notes to clarify difficult words, phrases, or ideas by providing their definitions or meanings within a specific context (AbuSeileek, 2008). Annotations or glossaries, as technology-enhanced tools, can present word meanings through various modes (e.g., textual, visual, auditory), formats (e.g., images, videos, audio clips, text), and positions within the text (e.g., side, bottom, or top margins; pop-up windows; or at the end of the text) (AbuSeileek, 2008).

Scholars widely support the use of annotations in facilitating vocabulary acquisition among EFL learners, particularly those that combine textual definitions with visual elements such as pictures (Yeh & Wang, 2003). Annotations have been shown to positively impact vocabulary learning by enhancing information processing and engagement. First, multimodal annotations—those that integrate different types of input—offer learners multiple channels through which to process and retain information (Boers et al., 2017; Yeh & Wang, 2003). For example, multimedia annotations can provide immediate access to word meanings through various formats, including text, audio, and visual aids (Martinez-Lage, 1997). Second, online annotations create interactive and motivating learning environments that support language practice (Lo et al., 2013). Such tools enable learners to access definitions or explanations of specific concepts directly within the text (Davis, 1989; Nation, 2001). Moreover, interactive glosses in multiple-choice formats have been shown to be particularly effective. In one study, 45 intermediate Thai EFL learners benefited from immediate feedback while verifying word meanings, which facilitated more effective vocabulary learning (Srichamnong, 2009).

Studies on annotation can generally be classified into three main categories: the presentation format of annotations, the effectiveness of different multimedia modes, and the impact of the type of information presented within annotations (Chen & Yeh, 2013). Empirical research has explored the influence of multimedia annotations on EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition, focusing on variables such as the location of annotations within the text (AbuSeileek, 2008, 2011) and the types of annotations used (Ahangari & Abdollahpour, 2010; Aljabri, 2011; Aldera & Mohsen, 2013; Yeh & Wang, 2003; Yoshii, 2006; Yoshii & Flaitz, 2002). While vocabulary learning remains a central focus (Sabet & Zarat-ehsan, 2014), several studies have also examined the role of annotations in enhancing reading comprehension (Chen & Chen, 2014; Chen & Yeh, 2013) and listening comprehension (Aldera & Mohsen, 2013; Jones, 2003, 2009; Jones & Plass, 2002) among EFL learners.

Yoshii (2006) investigated vocabulary retention among 151 adult English as a Second Language (ESL) learners at beginning and intermediate proficiency levels who received different types of annotations. The results indicated that learners who received both pictorial and textual annotations outperformed those who received only text-based or picture-based annotations. Similar results have been reported in other studies examining the impact of multimodal annotations on vocabulary acquisition. For example, Aljabri (2011) conducted a pre- and post-test vocabulary assessment with 88 male EFL learners in Saudi Arabia to evaluate the effects of various annotation types (L1 text-only, L2 text-only, L1 text-picture, and L2 text-picture). The findings revealed that participants in the L1 text-picture group achieved the highest scores in both immediate and delayed definition-supply tests. Similarly, Yeh and Wang (2003) employed pre- and post-tests along with a questionnaire to examine the effectiveness of four annotation types—auditory, visual-verbal (text), visual-nonverbal (pictures), and mixed modes—on the vocabulary acquisition of 82 Taiwanese EFL freshmen learning Thanksgiving-related terms. Their results showed that the combination of text and pictures was perceived as the most effective annotation type. However, the study also found that learners’ perceptual learning styles did not significantly influence the effectiveness of the annotations.

Moreover, Yeh and Wang (2003) emphasized the importance of raising EFL learners’ phonological awareness by highlighting the correspondence between spelling and pronunciation. Similarly, Al-Seghayer (2001) investigated the effects of multimedia annotations on vocabulary learning among 30 ESL learners in the United States, using questionnaires, interviews, and both production and recognition vocabulary tests. The findings revealed that video-based annotations were more effective than picture-based annotations for learning unfamiliar vocabulary. Al-Seghayer attributed this effectiveness to the video’s ability to create a mental image through a combination of vivid visuals, audio, and printed text. Consistent with Yeh and Wang’s (2003) conclusions, Al-Seghayer (2001) also stressed the importance of incorporating both written and spoken forms of word knowledge into vocabulary instruction.

Based on an analysis of vocabulary and reading comprehension tests as well as questionnaire responses, AbuSeileek (2008) found that intermediate adult EFL learners in Saudi Arabia who accessed online annotations outperformed those who used traditional glosses in both reading comprehension and vocabulary assessments. Regarding the location of annotations—whether at the end of the text, in the margin, at the bottom of the screen, or in a pop-up window—participants expressed a preference for marginal annotations, describing them as “easier” and “faster” to use. In a subsequent study, AbuSeileek (2011) investigated the effects of annotation placement on 78 college students in Jordan and similarly concluded that annotations positively influenced learners’ vocabulary acquisition and text recall, with glossaries placed immediately after the target word being particularly effective.

According to Nation (2001, 2005), knowing a word entails an understanding of its form, meaning, and use. Knowledge of word meaning encompasses awareness of its spoken and written forms, as well as its morphological components. Moreover, vocabulary knowledge includes both receptive (listening and reading) and productive (speaking and writing) dimensions. For example, understanding a word in its spoken form requires learners to recognize its pronunciation and produce it accurately. In terms of word form, learners must understand the relationship between form and meaning, including its conceptual and referential dimensions, as well as its associations with other words. Finally, knowledge of word use involves understanding its grammatical functions, common collocations, and the sociolinguistic and pragmatic constraints that govern its appropriate usage.

Mayer (2009) proposed the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML), which posits three primary memory systems: sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory. According to CTML, multimedia presentations combine verbal information (words) and visual information (pictures) to facilitate learning. Sensory memory processes acoustic representations (sounds) and iconic representations (images). These representations then enter working memory, where verbal and pictorial models are actively manipulated and integrated. Finally, prior knowledge or schemas stored in long-term memory interact with new information to support meaningful learning.

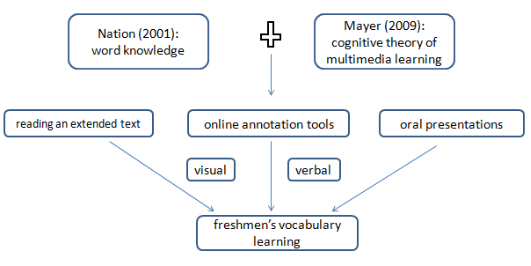

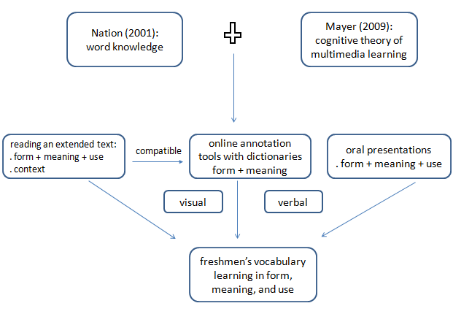

This study is grounded in a conceptual framework derived from Mayer’s (2009) Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) and Nation’s (2001) model of vocabulary knowledge, as illustrated in Figure 1. The participants acquired vocabulary through three primary activities: reading extended texts, utilizing online annotation tools, and delivering oral presentations. These activities provide both visual and verbal learning inputs that facilitate the acquisition of word knowledge—including word form, meaning, and use—by engaging sensory memory and working memory, and ultimately supporting the consolidation of knowledge into long-term memory.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework

Current empirical research on multimedia annotation tools predominantly focuses on the types and locations of annotations. However, these studies have largely overlooked the dimension of word knowledge within multimedia annotation tools. To date, no empirical research has specifically examined how multimedia annotation tools contribute to different aspects of word knowledge. This study addresses this gap by investigating the word knowledge facilitated by three online annotation tools and their impact on freshmen’s vocabulary learning. Furthermore, while prior studies have primarily employed pre- and post-vocabulary tests to evaluate the effectiveness of multimedia annotations on EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition, the present study adopts a more comprehensive approach. It analyzes EFL learners’ online projects, oral presentations, and questionnaire responses to provide a more nuanced understanding of vocabulary acquisition.

Method

This study adopts a case study approach, focusing on a real-life context as defined by Yin (2003)—specifically, a university course. The unit of analysis comprises the vocabulary learning of 26 Taiwanese freshmen facilitated through the use of online annotation tools.

Setting and participants

The case was selected using convenience sampling. The study involved 26 Taiwanese freshmen enrolled in an intermediate-level English course at National Hsinchu University of Education (now as National Tsing Hua University), a comprehensive university located in northwest Taiwan. All participants had studied English for at least nine years prior to university admission. Their intermediate proficiency level was determined based on their college entrance examination scores, which ranged from 11 (equivalent to 63.21 to 69.52 out of 100) to 13 (75.85 to 82.16 out of 100). The sample consisted of 22 females and 4 males. Most participants were majoring in Early Childhood Education (n = 18), followed by Art and Design (n = 5), and Physical Education (n = 3). The English course met once a week for 100 minutes throughout the duration of the study.

Data collection

The data collected in this study included participants’ annotation projects, audio recordings of their oral presentations, and responses to questionnaires. These data sources were used to investigate students’ vocabulary learning processes and the challenges they encountered while using the online annotation tools.

First, the textbook used in the freshman English class was Anderson’s Active II (2013). Active II has 12 units, and each unit contains two reading texts. Participants were asked to choose one online article related to the topics covered in the textbook. For Units 1 to 6, each participant chose one article and chose another article for Units 7 to 12. If all the articles were chosen, participants could choose articles related to their majors (early child education, art and design, or physical education). When the online article was chosen, participants used one of the following three online annotation tools for their projects: Lingro, VocaGrabber or WordSift 2. They read the article, chose five to 10 key words they had learned, copied and pasted what they had learned into a worksheet, made a list of the key words, and uploaded their worksheet to the school’s learning platform. After the mid-term and final exams, participants gave an oral presentation on their final projects. Participant oral presentations were recorded.

Unlike other annotation tools functioned as software needed to be purchased to be used in the empirical studies (i.e., AbuSeileek, 2008; Al-Seghayer, 2001), Lingro, VocaGrabber or WordSift 2 were free, easily accessed and operated. Learners typed in the website address of a reading text on Lingo and they clicked on word that they did not know. VocaGrabber and WordSift 2 functioned similarly. Learners cut and pasted any text into VocaGrabber or WordSift 2 and these two tools could quickly identify important words that appeared in the text and created word maps that blossom with meaning and branch to related words.

To elicit further participant feedback regarding the three online annotation tools, a questionnaire was designed based on the conceptual framework and two other studies: Aljabri (2011) and Al-Seghayer (2001). Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire at the end of the course. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part of the questionnaire was about participant demography in terms of name, age, gender, and language proficiency levels. The second part involved 14 open-ended questions regarding participants’ vocabulary learning through online annotation tools, such as their preference, difficulties they encountered, and their vocabulary learning.

Data analysis

Peer review performed by the researcher’s colleagues was employed during the data coding and analysis procedure. To ensure the trustworthiness of this study, triangulation was employed by comparing participants’ projects, questionnaires, and sound clips of the participants’ oral presentations. Descriptive statistics consisted of frequency counts obtained from the questionnaires and projects. Sound clips of the participants’ oral presentations were transcribed.

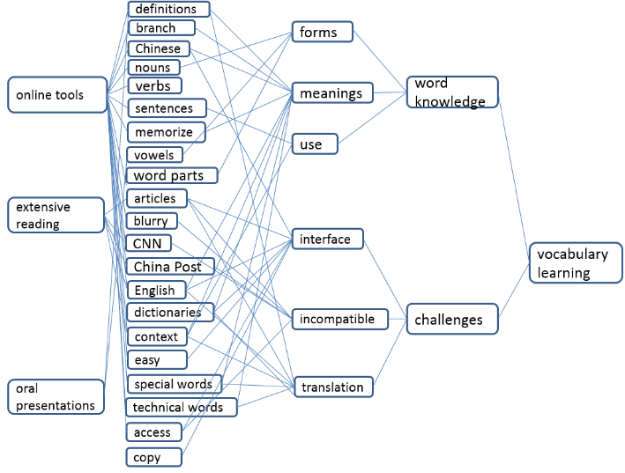

All the data were closely analyzed to identify any emerging themes and patterns, as in Figure 2. Since the data were all processed electronically, the researcher first read through the three major sources (online tools, reading an extended text, and oral presentations), labeled all the codes (i.e., definitions, branch, Chinese) and used consistent themes (i.e., forms, meanings, use). Based on the conceptual framework and research questions, major themes were identified (i.e., word knowledge, challenges) and finally into the overarching issue (i.e., vocabulary learning).

Figure 2.

Data Analysis

Analysis

Based on the data analysis and research questions, three issues were discussed in terms of the word knowledge provided by the online annotation tools, the 26 participants’ vocabulary learning through these online annotation tools, and challenges they faced while using these tools.

Word Knowledge Provided by the Online Annotation Tools

Of all the 52 projects completed by the learners, the majority were completed through Lingro (n=42, 80.7%). Only seven and three were completed through VocaGrabber (13.5%) and WordSift 2 (5.8%), respectively. The primary reason why participants chose one particular tool was because it was easy to use.

As outlined in Table 1, these three annotation tools provided limited word knowledge, and only for receptive skills. None of them provided word knowledge in terms of word use, but mainly for form and meaning. Language learners not only have to learn the spoken and written form of the vocabulary and its meaning, they also have to learn its grammar, collocation links, connotations, appropriateness of use, and relationships with other items in English and in learners’ L1 (Ur, 2012). Therefore, the primary word knowledge that language learners need to acquire include form, meaning and use (Nation, 2001).

Table 1

Word Knowledge Provided by Online Annotation Tools

|

Word knowledge |

|

Lingro |

WordSift 2 |

VocaGrabber |

|

|

Form |

spoken |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

written |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

word parts |

Receptive |

ü |

|

ü |

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

Meaning |

form and meaning |

Receptive |

ü |

|

ü |

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

concept and referents |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

association |

Receptive |

|

ü |

ü |

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

use |

grammatical functions |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

collocations |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

|

constraints on use |

Receptive |

|

|

|

|

|

Productive |

|

|

|

||

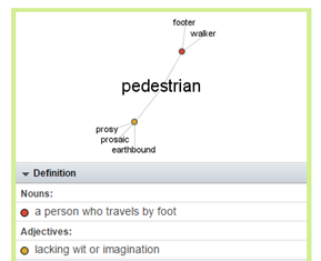

VocaGrabber provided three types of word knowledge including word parts, form and meaning; see the association of the word “pedestrian”, as in Figure 3, completed by Claire for her project. Claire wrote, “I like VocaGrabber because vocabulary words are organized in different categories with word parts, such as nouns, verbs, etc.” Learners can acquire vocabulary by making words from different components (Harmer, 2012). Learners can learn a word consisting of different elements: the root word, suffix and prefix. Moreover, learning word parts can also facilitate learners to acquire the word family of a single word, e.g., able: adjectives (i.e., able, unable), adverb (i.e., ably), noun (i.e., ability, inability, disability), and verbs (i.e., enable, disable).

Figure 3.

Claire’s Project via VocaGrabber

Figure 4 is Ivy’s project via Lingro. Lingro provided word parts (i.e., noun, verbs) and word meaning. Mimi wrote, “I like Lingro, because I can click on the words I do not know. Lingro provides clear word definitions and meanings”, and Janet wrote, “I can easily understand the English definitions.” This is in accord with AbuSeileek (2008), in that participants prefer marginal glosses because they can click on a word, and see the meaning of the word near the same line in the text. The access to the annotation tools provides language learners with the desired meaning immediately while they read, without stopping to look up words in a dictionary (Martinez-Lage, 1997).

Figure 4.

Ivy’s Project via lingro

However, Iris identified a problem with Lingro: “Lingro provides only simplified Chinese definitions, but not definitions in traditional Chinese. I cannot read the simplified Chinese characters.” In addition, Chloe wrote, “It would be better if Lingro could provide some sentences or examples rather than word definitions alone.” These concerns regarding the provision of sentences or examples are in accord with Srichamnong (2009). The interactive, multiple-choice gloss, referring to the target word with L1 equivalents (one correct, one semantically related and one opposite meaning translation) in Srichamnong (2009) helped Thai EFL learners to acquire more in-depth vocabulary. Once target words were chosen, learners inferred the correct meaning from the context, based on the choices provided in the glosses.

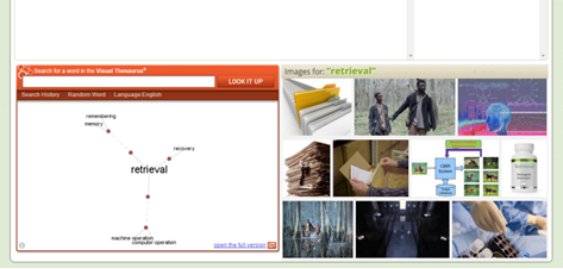

WordSift provided word knowledge primarily through word associations, as illustrated in Figure 5. For example, the word “retrieved” was linked to related terms such as “memory,” “recovery,” and “machine operation,” based on the article selected by Wendy. One participant, Allie, commented, “I like the branches, because they help me to associate words.” In contrast, Rosita expressed dissatisfaction, stating, “WordSift did not provide word definitions. I did not understand the word meanings.” Research suggests that associations or word maps can facilitate vocabulary retention by promoting cognitive engagement. Unlike rote drilling or repetition, word associations encourage learners to categorize words and form meaningful relationships among them (Harmer, 2012). As an effective vocabulary learning strategy, word associations involve creating links among listed items and organizing groups based on associative attributes, such as part-whole relationships.

Figure 5.

Wendy’s Projec via WrodSift

Vocabulary learning through online annotation tools

With regard to the vocabulary learning through these three online annotation tools, the most success was with “learn more words and their meanings” (n=18), followed by “word associations” (n=6) and “review vocabulary words” (n=2). Ivy claimed, “When I browse through the article and I encounter words that I don’t know, I click on the word and I can know the meaning. It can save my time. Moreover, the definitions are written in English. When I read the definitions, I learn more words and have a deeper understanding of the words.” Ling and Chloe agreed with Ivy’s ideas of English definitions and they all claimed, “English definitions help me understand and memorize the meanings of the vocabulary words.”

Reading English definitions in this study aided participants such as Ling and Chloe in gaining a better understanding of English vocabulary. Miyasako (2002) investigated the effects of L1 and L2 glosses on vocabulary acquisition and found that learners who used L2 glosses significantly outperformed those who used L1 glosses on immediate tests. Furthermore, Miyasako (2002) concluded that L2 glosses tend to be more effective for learners at higher proficiency levels, whereas L1 glosses are more beneficial for learners with lower proficiency.

Regarding vocabulary expansion, participants Allie and Tania emphasized the importance of word association, noting improvements in both word recognition and associative skills. Research suggests that annotations combining text or definitions with pictures engage multiple areas of the brain, promoting deeper cognitive processing than text or definitions alone (Ahangari & Abdollahpour, 2010). This aligns with findings that visual memory plays a crucial role in learning, as learners tend to remember images more effectively than words (Underwood, 1999).

In addition to learning these words visually, participants were asked to give oral presentations on the projects. They read through the projects as one of the examples in the following scenario. Chloe demonstrated her word knowledge in terms of receptive word association, receptive word parts, receptive meanings (Chinese and English definitions), receptive collocations (understanding the meaning in the context of the article), and spoken form. Chloe had difficulties in pronouncing the vowels of the words “dubious” and “arousing.”

Scenario 1: Chloe’s Oral Presentation

Chloe: (read the word dubious) [dʌ]

Instructor: [ˋdjub]

Chloe: [ˋdjubaɪ]

Instructor: [djubɪəs]

Chloe: [djubɪəs]

Chloe: Adjective.

Instructor: It’s an adjective.

Chole: (arousing doubt) [raʊz] [doubt]

Instructor: [əˋraʊzɪŋ]

Chole: [əˋraʊzɪŋ] [doubt]

Although Chloe experienced difficulties pronouncing words such as dubious and arousing, the visual support provided by the online annotation tools, combined with verbal practice during oral presentations, contributed to improvements in her vocabulary learning. This supports the idea that integrating both verbal and visual representations through multimedia enhances vocabulary acquisition (Ahangari & Abdollahpour, 2010). Chun and Plass (1996) also emphasize that learners benefit when they connect verbal and visual information in working memory, as these connections facilitate the organization and integration of new information into existing mental models stored in long-term memory.

Challenges of using the tools

The most frequently reported challenge among participants was an “incompatibility problem” (n = 16), followed by “the interface of the tool is in English” (n = 6), and “inability to find definitions” (n = 4). The incompatibility issue primarily stemmed from Lingro’s limited ability to process certain websites. For instance, Lingro was unable to load or annotate articles from CNN, causing the webpage to appear distorted or blurry, as illustrated in Figure 6. As a result, participants had to seek alternative sources. One participant, Maggie, shared her experience: “I wanted to read articles from CNN but in vain. So I searched articles from the China Post.” This limitation influenced learners’ selection of reading materials and suggests a need for greater tool compatibility with a broader range of authentic online texts.

Figure 6.

Blurry Page on Lingro

Second, since these three tools have English interfaces, it was difficult for EFL learners to easily use these three tools. It may take a little time to become familiar with them. Jeff wrote, “I tried hard to figure out how to use the website.” Rosita also wrote, “It was difficult in the very beginning, because the tool is in English. After using it for a while, it became easier.”

The annotation tools used in this study are in English rather than the learners’ first language. Chen and Yen (2013) recommend that instructors provide learners with an orientation on how to effectively use these annotation tools. Such instruction and demonstration can increase learners’ awareness of the tools’ features and enhance their ability to utilize them for improving English proficiency (Al-Ali & Gunn, 2013). By receiving proper guidance, learners are better positioned to maximize the benefits of these supportive technologies.

Next, participants claimed that not all word meanings could be easily found via the three tools, particularly the proper noun or technical terms. Participants used other definitions to find the meanings or read the words from the context. Chloe responded, “I cannot find the definitions via the tool, so I used other tools.” Kelly also responded, “The definitions from special words cannot be accessed, such as kryptonite, or in-your-face. So I tried to read the article again and again.”

The difficulties experienced by Chloe and Kelly reflect Ko’s (1995) observation that annotations in many textbooks and software predominantly focus on providing meanings in either the learners’ first language (L1) or the second language (L2). However, as Ur (2012) notes, an English word may not always have a direct equivalent in the learners’ L1, which can complicate the annotation process and learners’ comprehension.

Discussion

This study explored the influence of three online annotation tools on 26 Taiwanese EFL freshmen’s vocabulary learning. Based on the conceptual framework drawn from Mayer’s (2009) CTML and also Nation (2001), word knowledge, the data analysis of participants’ projects, questionnaire, and sound clips from participants’ oral presentations indicated the following major findings. First, these three tools provided limited word knowledge in terms of association, word parts, and meanings. Second, the tools focused more on word knowledge than on receptive skills. Third, participants suggested that word meanings provided through the annotation tools should be presented in both the participants’ first language and also the target language. The annotation tools should also provide sentences and clear definitions. Fourth, participants gained word knowledge, particularly in meanings and association. Fifth, participants faced three major challenges: (1) the tools were easy to use for the majority of participants but the interface was completely in English, (2) some of the online articles were incompatible with the online annotation tools, and (3) the annotation tools were limited and no definitions could be retrieved based on some of the technical words or terms.

Based on the above major finding analyzed based on the conceptual framework in Figure 1, in order to have an effective integration of online annotation tools to foster EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition, a new framework was revised, as in Figure 7. First, reading an extended text can provide visual presentations for learner and be used to develop learners’ word knowledge in form, meaning and use. Second, reading an extended text can provide a rich context for learners’ vocabulary learning. Third, the online articles for should be compatible with the online annotation tools. Fourth, online annotation tools can be used with other online dictionaries in order to provide EFL learners with visual presentations on word knowledge in form and meaning. Fifth, the oral presentations provide the EFL learners with both visual and audio presentation and opportunities to demonstrate their word knowledge in form, meaning, and use.

Reading an extended text, checking vocabulary via online annotation tools compatible with online dictionary, and giving oral presentation can provide both visual and verbal forms of vocabulary learning in order to help freshmen acquire word knowledge in word form, meaning, and use from sensory memory, working memory, and then into long-term memory. In order to effectively use the new framework for EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition, two major issues should be taken into consideration in terms of complete word knowledge as rich input, and learners’ demonstration of word knowledge.

Figure 7.

Integration of Annotation Tools on EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Learning

Complete word knowledge as rich input

The three online annotation tools in this study provided only limited word knowledge. Language teachers can search for other annotation tools with complete word knowledge, such as definitions, synonyms, grammatical notes, translations, cultural or historical references, or even guiding questions (AbuSeileek, 2008). Such annotation tools can provide language learners with rich input, increase their vocabulary learning (Sabet & Zarat-ehsan, 2014), and enhance their reading comprehension (Chen & Yeh, 2013). Annotation tools can become useful language learning aids (AbuSeileek, 2008). Moreover, Davis and Lyman-Hager (1997) claim that annotation tools can facilitate language learners to become independent because they can find the definitions on their own without asking others to help them.

Learners’ demonstration of word knowledge

Through visual presentations using online annotation tools, reading extended texts, and delivering oral presentations, participants in this study demonstrated various aspects of word knowledge, including receptive word association, recognition of word parts, receptive meanings, receptive collocations, and productive spoken forms. To further support learners in showcasing their word knowledge, specific instructional strategies and classroom practices can be implemented. For example, during oral presentations, learners can be encouraged not only to read aloud the target words and their definitions but also to elaborate on additional word knowledge. This may include discussing typical collocations, identifying appropriate or inappropriate contexts for use, exploring related words within the same word family, and composing sentences that connect two or more vocabulary items (Ur, 2012).

Conclusion

This study moved beyond the current empirical studies on annotations, their effectiveness, and types. This study has the major findings. First, these three annotations tools provided limited word knowledge in terms of association, word parts, and meanings. Secondly, the annotation tools helped participants gain word knowledge, particularly in meanings and association. Findings drawn from this study extend knowledge in the emerging area of annotation. From a theoretical perspective, the conceptual framework demonstrated the importance of examining EFL learners’ vocabulary acquisition. The conceptual framework offered a detailed explanation of how learners can acquire word knowledge in terms of use, form and meanings via visual and verbal means.

Several limitations were present in this study. The first concern was the small size of the participant sample (26) and the limitation in the duration of the study (one semester). In order to have a clear picture of Taiwanese EFL freshmen’s vocabulary learning through online annotation tools, this study can be replicated with learners of various majors and age ranges at different universities. A further study can be devised for longer periods. Second, the participants shared similar backgrounds. They were at the intermediate English proficiency size and had completed 9.5 years of English instruction starting from elementary school. Therefore, further studies can focus on EFL learners at lower or more advanced proficiency levels.

References

AbuSeileek, A. (2008). Hypermedia annotation presentation: Learners’ preferences and effect on EFL reading comprehension and vocabulary acquisition. CALICO Journal, 25(2), 260-275.

AbuSeileek, A. F. (2011). Hypermedia annotation presentation: The effect of location and type on the EFL learners’ achievement in reading comprehension and vocabulary acquisition. Computers & Education, 57(1), 1281-1291.

Ahangari, S., & Abdollahpour, Z. (2010). The effects of multimedia annotations on Iranian EFL learners L2 vocabulary learning. The Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 1-18.

Al-Ali, S., & Gunn, C. (2013). Students and teachers expectations of web 2.0 in the ESL classroom: do they match? Study in English Language Teaching, 1(1), 156-171.

Aljabri, S. S. (2011). The effect of pictorial annotations on Saudi EFL student’s incidental vocabulary learning. Journal of Arabic and Human Sciences, 2(2), 43-52.

Aldera, A. S., & Mohsen, M. A. (2013). Annotations in captioned animation: Effects on vocabulary learning and listening skills. Computers & Education, 68, 60-75.

Al-Seghayer, K. (2001). The effect of multimedia annotation modes on L2 vocabulary acquisition: A comparative study. Language Learning & Technology, 5(1), 202-232.

Boers, F., Warren, P., Grimshaw, G., & Siyanova-Chanturia, A. (2017). On the benefits of multimodal annotations for vocabulary uptake from reading. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(7), 709-725.

Chen, C. M., & Chen, F. Y. (2014). Enhancing digital reading performance with a collaborative reading annotation system. Computers & Education, 77, 67-81.

Chen, C. M., Li, M. C., & Lin, M. F. (2022). The effects of video-annotated learning and reviewing system with vocabulary learning mechanism on English listening comprehension and technology acceptance. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(7), 1557-1593.

Chen, I. J., & Yen, J. C. (2013). Hypertext annotation: Effects of presentation formats and learner proficiency on reading comprehension and vocabulary learning in foreign languages. Computers & Education, 63, 416-423.

Chun, D. M., & Plass, J. L. (1996). Effects of multimedia annotations on vocabulary acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 80(2), 183-198.

Davis, N. (1989). Facilitating effects of marginal glosses on foreign language reading. The Modern Language Journal, 73(1), 41-48.

Davis, N., & Lyman-Hager, M. (1997). Computers and L2 reading: Student performance, student attitudes. Foreign Language Annals, 30(1), 58-72.

Huang, Y., Zou, D., Wang, F. L., Kwan, R., & Xie, H. (2020). Investigating the effectiveness of vocabulary learning tasks from the perspective of the technique feature analysis: The effects of pictorial annotations. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 27(3), 254-273.

Jones, L. (2003). Supporting listening comprehension and vocabulary acquisition with multimedia annotations: the students’ voice. CALICO Journal, 21(1), 41-65.

Jones, L. (2009). Supporting student differences in listening comprehension and vocabulary learning with multimedia annotations. CALICO Journal, 26(2), 267-289.

Jones, L., & Plass, J. (2002). Supporting listening comprehension and vocabulary acquisition in French with multimedia annotations. The Modern Language Journal, 86(4), 546-561.

Ko, M. H. (1995). Glossing in incidental and intentional learning of foreign language vocabulary and reading. University of Hawai’i Working Papers in ESL, 13(2), 49-94.

Lo, J. J., Yeh, S. W., & Sung, C. S. (2013). Learning paragraph structure with online annotations: An interactive approach to enhancing EFL reading comprehension. System, 41(2), 413-427.

Martinez-Lage, A. (1997). Hypermedia technology for teaching reading. In Bush, M. & Terry, R. (Eds.), Technology enhanced language learning, (pp. 121-163). National Textbook Company.

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Miyasako, N. (2002). Does text-glossing have any effects on incidental vocabulary learning through reading for Japanese senior high school students? Language Education & Technology, 39, 1-20.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

Papin, K., & Kaplan-Rakowski, R. (2024). A study of vocabulary learning using annotated 360 pictures. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(5-6), 1108-1135.

Sabet, M. K., & Zarat-ehsan, M. (2014). The impact of multimedia glosses on intermediate EFL learners’ vocabulary learning and retention. International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 7 (3), 599-608.

Srichamnong, N. (2009). Incidental EFL Vocabulary Learning: The effects of interactive multiple-choice glosses. ICT for Language Learning, Florence, Italy.

Underwood, J. (1984). Linguistics, computers and the language teacher: a communicative approach. Newbury House.

Ur, P. (2012). A course in English language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Wolfe, J. (2002). Annotation technologies: A software and research review. Comput. Compost. 19, 471-497.

Yeh, Y., & Wang, C. W. (2003). Effects of multimedia vocabulary annotations and learning styles on vocabulary learning. Calico Journal, 131-144.

Yin, R. K. (2003). A case study research: Designs and methods. Sage.

Yoshii, M. (2006). L1 and L2 glosses: Their effects of incidental vocabulary learning. Language Learning & Technology, 10(3), 85-101.

Yoshii, M., & Flaitz, J. (2002). Second language incidental vocabulary retention: The effect of text and picture annotation types. CALICO journal, 33-58.

Zhang, R., & Zou, D. (2020). Influential factors of working adults’ perceptions of mobile-assisted vocabulary learning with multimedia annotations. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 14(4), 533-548.

Zou, D., & Teng, M. F. (2023). Effects of tasks and multimedia annotations on vocabulary learning. System, 115, 103050.

Please check the Pilgrims in Segovia Teacher Training courses 2026 at Pilgrims website.

Reducing Second Language Learning Anxiety Among ELT Diploma Trainees in Sri Lanka: The Role of AI Duolingo

Priyanka Kumarasinghe, Sri LankaTaiwanese Freshmen’s Preferences and the Effects on Vocabulary Acquisition of Online Annotation for Reading an Extended Text

Chin-Wen Chien, TaiwanAssessing Listening Placement Tests in English through Digital Technologies

Alexis Vasquez, ColombiaFormative Assessment Using Time Sequenced Analysis: Assessing Learning According to the Way Languages are Acquired

Miriam C.A. Semeniuk, Canada