- Contents

- Various Articles - Trends – something old, something new

- The What, Why and How of CLIL for English Teachers

The What, Why and How of CLIL for English Teachers

Aleksandra is a Geography and English teacher from Toruń, Poland, with 30 years of experience in Geography and EFL/ESL teaching, teacher training, translating, examining and materials writing, including over 10 years of Content and Language Integrated Learning. She has worked extensively as a teacher and teacher trainer in Poland, the UK (incl. Pilgrims) and other European countries, as well as in Asia (Qatar, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iraq and China). She regularly conducts CLIL training for teachers in Poland for a local publishing company. In 2014 her geography workbook for lower secondary ‘Earth and People 1’ was nominated for the British Council ELTons Award in the category of Local Innovation and in 2016 she was the winner of the award as a Tigtag CLIL team member.

Aleksandra has presented at national and international conferences, such as IATEFL World, IATEFL Poland and HERODOT network, mostly on topics related to CLIL and Global Issues in an English classroom. In April 2019, she is going to be a plenary speaker at the 53rd International IATEFL Conference in Liverpool.

Introduction

One of the courses offered by Pilgrims deals with CLIL methodology, that is combining teaching non-linguistic concepts through the vehicle of a foreign language. The acronym stands for ‘Content and Language Integrated Learning’ but in fact when English is involved the more precise terms should say ‘Content and English Integrated Learning’, or CEIL.

About twenty-five years from coining the term CLIL (1994; Coyle et al. 2010) it is time to make it more ‘English teacher-friendly’. In this short article I would like to dissect the notion of CLIL in an English classroom and offer some suggestions on what, why and how to introduce content during regular English classes.

What is CLIL?

Originally, the idea of language practitioners involved in this type of teaching and teacher training was based on the fact that subject teachers often lacked both linguistic mastery and methodological knowledge on how to combine their subject with the foreign language requirements (so called ‘hard CLIL’). Recently, however, English teachers, followed by major publishers, have realised CLIL gives yet another opportunity to increase students’ motivation to learn foreign languages (‘soft CLIL’).

In fact, the very term CLIL wrongly suggests that there are two separate elements that need special attention if we want to combine them in one lesson. In reality, there is no content without the language and there is no language without the content. Subject teachers are responsible for teaching their students the language of this very subject, be it geography, history or physics. Without it, there will be no communication between students and the teacher on the concepts this subject is trying to teach (Green 2016). And the other way round - no language lesson is possible without some text to read. So, advocating for more content in an English classroom means a more conscious approach to the process, rather than a revolution in education.

Why should you try it?

One of the more obvious reasons for engaging in CLIL is the exposure of the students to some academic vocabulary, which might be useful in their later careers. Moreover, as the usual content included in the general English coursebooks revolves around history, literature, arts, customs and/or geography of various countries, especially the English-speaking ones, tapping into the wider curriculum might be of interest to those keen on chemistry, physics or other disciplines. The engagement in a task, especially when the language itself is used as a tool rather than an ultimate goal, might boost students’ grasp of the language.

There is at least one more reason for involving more content in a foreign language class. Since the 19th century, for pragmatic reasons school curricula have been chopped into smaller and smaller bits of knowledge. As various disciplines do overlap and rely on each other, teachers and educators alike often stress the need to counteract this fragmentation through interdisciplinarity, at least during some classes. Maths is the basis for physics, there are strong correlations between biology and chemistry, whereas literature cannot function without the historic background. In fact, almost all traditional school subject can be linked to each other, besides foreign languages. Language curricula, revolving around grammar points and language functions, are not in any way related to other school subjects, especially in higher school levels. If introduced properly, CLIL might bridge this gap making the language curriculum at least partly reflect the curricula of other subjects.

How to do it?

Convincing English teachers to try and include some non-linguistic content into their repertoire might not be the biggest challenge. In the end, the aim is to help students master the language, and if there is a method that helps achieve just that, no teacher needs to think twice. A completely different issue is, however, giving the teachers enough guidance and tools to successfully introduce some biology or geography content into their teaching.

The original rule of 4Cs of CLIL, developed by Coyle (2010), that is Content (concepts to be taught), Communication (language needed in the process), Cognition (thinking processes involved) and Culture (awareness of self and ‘otherness’) can be further extended into 10 CLIL parameters, as suggested by Ball, Clegg and Kelly (2015). These authors, in their book Putting CLIL into Practice for the first time address the concept of ‘soft CLIL’.

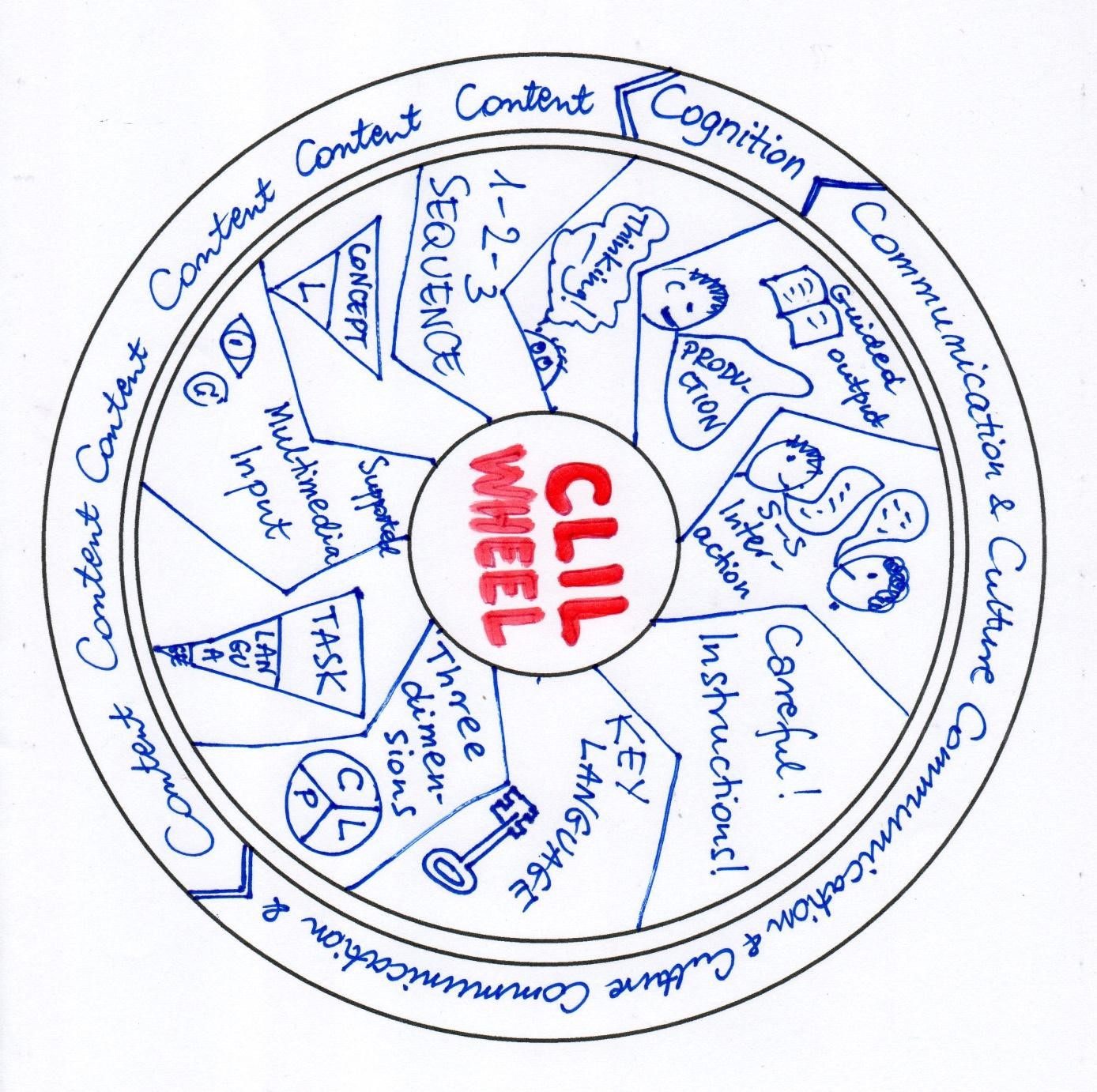

CLIL Wheel of 10 parameters

Although the authors list the ten parameters, it seems that there are no more or less important issues to be tackled when introducing content in an English classroom. This way the idea of a CLIL Wheel has been developed by the author. It treats all the elements as equally important. Moreover, it tries to merge the 10 characteristics of a CLIL lesson with the 4Cs.

- CONTENT

- 1-2-3 Sequence

One of the issues a language teacher is advised to remember, is that the subject curricula offer a specific sequence of knowledge, unlike the language curriculum which revolves around grammar points. So, it is crucial that the language teacher designes a sequence of lessons rather than offer the students one randomly selected theme. This could be, for instance, a series of lessons of the life on the Tudor court or a series of lessons on acids and bases. This way, the teacher and the student will be able to refer to the previous lesson or lessons and see the connection between different elements of the curriculum. Even if this is the first lesson, students do have prior knowledge so it is a good idea to evoke interest by referring to what students already know in a given field.

- Concept > Language

What might be hard to digest for language teachers is the idea that in a CLIL setting the lessons are concept-driven rather than language-driven, even if delivered during a general English class. However, the language used to teach a specific concept is dictated by this very concept. If we decide to offer students a lesson on history, they would have to use Simple Past tense even if they have not studied it in an English class. If we want to compare the structure of a plant cell with an animal cell, we need to teach a large number of specific vocabulary items, such as mitochondria and cell membrane. It does not mean the language is not important, but just that the language is a tool to understand the studied concept rather than the goal of the lesson.

- Guided multimedia input

Input means all the information directed at the students. As such, it needs to be carefully designed and delivered. It also should be ‘chopped’ into smaller bit rather than delivered to students in large chunks. After every input instance, the teacher should stop and check understanding before moving on. The word ‘multimedia’ clearly delivers the message - the content should be accompanied by a plethora of, mainly visual, tools. Although it goes without saying that modern classroom often uses multimedia, in a CLIL setting it becomes even more important. Mini-films with appropriate commentary would help students understand concepts better that a dry description of the same process in a textbook. Last but not least, this multimedia input should be guided. In this regard, language teachers can easily design pre-, while- and post-watching tasks to make sure that the students do not just sit idly watching a video but have support in the form of handouts to refer to.

- Task > Language

Whatever task the teacher decides the students need to do in a CLIL class, it becomes the factor leading the language. Depending on the nature of the task, the students might need the appropriate language to describe the process or talk about a sequence of events. This would require specific language items, such as first, later and then, and they need to be limited to the necessary ones.

- COMMUNICATION & CULTURE

- Key language

Key language items need to be highlighted and made salient. This is because the students will not be able to discuss the studied concepts if they do not understand and cannot write and pronounce the necessary vocabulary. The teacher can follow the six-step process of dealing with academic vocabulary designed by R.J. Marzano (2004), which involve stages aimed at presenting, personalising and recycling vocabulary, or use elements of Interactive Science Notebook. As vocabulary is part of general language classes, the teacher has a variety of ways of managing this issue, from odd-one-out, crosswords, word-search squares and bingo to multiple choice tasks and picture dictionaries.

- Careful! Instructions!

The relationship between the text the students are to read or the video they need to watch and the task they are to do is based on what lies in between, that is instructions. They should be carefully planned and staged so as not to add to the burden of understanding the text/video and doing the task. An important issue here is whether the students actually know what to do. A simple question: Do you know what to do? is not going to prevent problems. Some students find it difficult to acknowledge they do not know what the task entails. Thus, the teacher should ask more detailed questions, like: How many pieces of information do you need to find? or What are you going to do when you finish the task?

- S-S interaction

A well-designed CLIL lesson should also include ample opportunities for students to interact in pairs or groups. This might seem obvious for a language teacher that students need to practice the language. However, in a CLIL setting student-student interaction has an extra weight. It is the time for checking the understanding of the content and the correctness of language the students need to express the studied concept. It is the time to rehearse the answer to the task before it can be given to the class. This postponed answer to the teacher’s question or the written task is an important element of the CLIL lesson.

- Supported output

Another crucial issue is supporting the students’ output, both written and oral. Again, here language teachers can use their typical repertoire, like substitution tables or models of written texts. Another great tool are graphic organisers, which help organise not only vocabulary but also content, and thus can support oral and written production as well as revision.

- COGNITION

The fact that the students are learning a non-linguistic content through a foreign language does not mean the teacher needs to simplify knowledge or spoon-feed the students. On the contrary, they need to be challenged so as to make sure they grasp the concepts to be learnt. They need to be physically engaged and/or mentally involved in the learning process.

- THREE DIMENSIONS OF CLIL

Last but not least, the idea of three dimensions of CLIL spans across both content and communication. At the base of it is the realisation that besides the content and the language every CLIL lesson includes some procedures, that is the technicalities of what needs to be done with the content using the language as a vehicle. Before the lesson the teacher needs to decide, which of those three elements is potentially going to pose the largest difficulty for the students. If this is the content itself, it needs to get special attention and support. On another instance, this might be the language needed to describe a process. The vocabulary thus would need extra work on pronunciation, spelling and meaning. The last element in this trio is a procedure. This may mean reading the text on similarities and differences, for example of the Arctic and Antarctica, and transferring the information into a two-circle Venn diagram. If the students have never seen or made such a graphic organiser, the procedure might require extra time and careful explanation.

Content to consider

Once we know the what, why and how of CLIL in an English classroom, there is one last issue to address, that is to decide what content to choose. English teachers may be tempted just to stick to ‘CLIL pages’ offered by coursebooks they use in their everyday work. Such an approach, although is does focus on some subject-specific content, is somewhat crippled. First of all, in no way can it be connected with the themes covered by the students in the subject lessons at that very moment. Thus, such a random ‘CLIL lesson’ still does not tune into the real-life school curricula in non-linguistic subjects. Moreover, ‘CLIL pages’ offer a little bit of everything with no continuation in terms of the content. A ‘CLIL page’ on 2D figures in maths in one unit has no connection whatsoever with the types of animal groups in the following unit.

In order to make ‘CLIL pages’ a meaningful learning experience, why not consulting the subject teacher on what the class is actually studying in their lessons at the moment? Maybe they are not doing 2D figures but some completely different Maths topic. Then the English teacher can take a decision whether to postpone the ‘CLIL page’ content or maybe substitute it for something that the students are actually covering. Whatever the decision, it would be great if the content was extended into a series of lessons on a given topic, rather then be just one incident.

Another suggestion is to try and ‘extend’ the traditional content offered by coursebooks, such as clothes, food or technology, and introduce some global issues. In terms of the first theme, this can be a project studying shopping habits of the class, exploring the information on sustainability and social programmes of leading clothes producers or checking what it takes to produce one pair of jeans. Food can be explored in terms of its origin (food miles) or food waste, while a technology project might explore what goes into producing a mobile phone and what happens to those devices we have stopped using.

Last but not least, the teacher can act irrespectively of the English coursebook and consider teaching non-linguistic content that he/she feels comfortable in. Whatever the subject, it is highly recommended to consult with the subject teacher to either cover a similar theme (e.g. practising fractions in English at the same time the students are doing it in Maths) or extend the theme the students are studying in the subject class (e.g. get a more detailed insight into the court of Henry VIII at the same time when the students are studying the history of the 16th century). One theme that always works well with younger students revolves around science delivered through catchy experiments, like making a lava lamp or catching gas in a balloon. Such content is both engaging and academic language-rich.

Final remarks

Whatever the content the English teacher chooses, there are a few challenges ahead. One of them might be connected with the fact, that the language itself takes the secondary role in a CLIL setting. As a result, there is no need to correct every linguistic error as long as the students are communicative and they do show the grasp of the concept we were trying to teach.

Yet another issue is the teacher’s lack of confidence in their content knowledge. This is why is is advisable language teachers try to select the themes that are closest to their hearts. Besides, there is nothing wrong in admitting that we do not have the expertise to explain all the issues related to the theme of the CLIL lesson. In such a case, the teacher may simply refer the students to their subject teacher or ask them to research the issue on their own. It would also be good to seek the subject teacher’s advice. It is them, in the end, who are experts on their subject.

Last but not least, there is the question what and how to assess from a series of CLIL lessons. As soft CLIL refers to a language class should we stick to the language? What about the content then? Should it be omitted altogether? This is the teacher’s decision, but it is advisable that the content knowledge is included in the assessment. This way we would send a signal to the students, that it does matter how they deal with the concept the series of CLIL lessons has been on. Whatever the decision, the students need to be aware of what lies ahead in terms of the assessment.

Bibliography

Ball, P., Kelly, K. & Clegg J. (2015). Putting CLIL into Practice. Oxford Handbooks for Language Teachers. Oxford: OUP.

Coyle, D., Hood, P. & Marsh, D. (2010). Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Green, C. (2016). How to Teach Secondary Science. Carmerthen, Wales: Independent Thinking Press.

Marzano, R.J. (2004). Building Background Knowledge for Academic Achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Please check the CLIL for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website

The What, Why and How of CLIL for English Teachers

Aleksandra Zaparucha, PolandStories: Their Importance In and Out of the Classroom

Andrew Wright, HungaryYou Are Never Too Old to Learn But You Can’t Teach an Old Dog New Tricks… Some Reflections on Teaching

Malgorzata Szwaj, Poland