The Art of Writing Tests for Dyslexic Students

Barbara Skrok is a teacher, teacher trainer and a conference speaker. She helps students with special educational needs and she particularly enjoys working with dyslexic students. She is an author of training videos available on Pearson websites and an online course for eduNation. E-mail: 1basia.s@interia.pl

Special Educational Needs. Dyslexia. Dyslexic Students. These are words that teachers often hear. But do they know exactly what these words mean?

Some of the teachers describe dyslexia as a kind of disability or disease, while others still believe that dyslexic children can outgrow the disorder.

In fact, dyslexia is neither a learning disability nor a disorder - it’s a learning difference specific for every single learner. It’s a lifetime condition and can never be cured. It manifests itself in difficulties such as word-decoding, reading, spelling and other learning-related skills. But it will affect dyslexic students throughout their lives.

Dyslexia might be of different types or degrees or strength variations and because of these factors each dyslexic learner is unique, and has a personal characterization. No two individuals with dyslexia are alike so they should not be treated in the same way by their teachers.

Along with poor literary skills learners with dyslexia can have:

- a shorter memory span (they can remember fewer pieces of information at one time)

- motor skills problems

- difficulty organizing tasks

- poor concentration

- attention problems (they often face difficulties to sustain their attention for a long time)

- problems with processing verbal instructions

- slow speed of processing

- emotional problems

- low self-confidence and motivation

Not all these symptoms are innate in each person and it doesn’t mean that dyslexic learners have only weaknesses. They might be exceptionally creative in problem-solving. Thinking ‘outside the box’ they can come up with excellent ideas. They are picture-thinkers and have fantastic visual skills. Students with dyslexia often see things more holistically and, what seems to be most important, is that they are not less intelligent than their non-dyslexic peers, they just need more time, more effort and more self-confidence to be able to succeed.

Having dyslexic students in a foreign language teaching classroom is not only a challenge, but it is a kind of mission. The teacher’s role is to find such strategies, techniques, methods and activities which are dyslexic-friendly. Their role is also to stop all the negative feelings dyslexics experience in their school career: humiliation, low self-esteem, failure or even fear of attending school.

Whenever we ask dyslexic students what the worst thing about school is, they answer in one word only: TESTS.

Testing is a kind of assessment whether the objectives of the course or unit are achieved.

Do the tests results always precisely mirror the level, skills and competence of dyslexic learners?

Teachers should bear in mind that the reading difficulties dyslexic students experience affect all language skills and consequently will never provide ‘real’ information about their actual knowledge. Sometimes they cannot understand the questions therefore cannot answer them correctly. But in many cases, even if they do know the answer, they make a lot of mistakes while writing them down.

Many, if not most, teachers feel they are not appropriately trained to deal effectively with learners who have dyslexia in a classroom context and complain that preparing handouts or tests for students with special educational needs is a nightmare.

No wonder. There is a great lack of generally accepted rules and regulations how to write, compose or prepare tests and handouts for dyslexic learners.

There are some solutions and arrangements called ‘accommodations’ offered to learners in order to help them prove their skills and knowledge. They can deal with:

- classroom management

- special conditions during tests or exams

- curriculum

- feedback

- homework

- timing

but none of them inform what should or shouldn’t be in the tests or appropriately-prepared handouts.

Kormos J. and Smith A.M. in their book ‘ Teaching languages to learners with specific learning difficulties ( 2012 p. 160) draw teachers’ attention to some important questions to consider in selecting and designing assessment tasks.

The questions they form can direct teachers towards the proper path which can show them what to concentrate on:

- Does the task measure the targeted skills or knowledge?

- Is the task relevant for the students?

- Can the task be marked reliably?

- What kind of difficulties might students with dyslexia experience when doing the task?

- Is the time needed to complete the task sufficient for students with dyslexia?

- Are the instructions clear?

- Is the level appropriate?

All these questions seem to be the perfect guideline to test strategies that are easy to put into practice.

Good teaching is possible with bad testing but bad teaching

cannot result in good testing.

Marina Marinova, Humanising Testing.

Pilgrims June 2019

Timing

Allotting extra time in testing is one of the most essential in the case of dyslexic students, because:

- they read more slowly than their peers so they might not find the time sufficient to complete all the tasks as their eyes work more slowly

- they are not fluent enough in automated reading

- they usually do not have enough time to double check the test

- sometimes they lose precious minutes on the test because it takes them longer to overcome their stress while working towards a time deadline

- generally, dyslexic students have problems with time management

Researchers found that dyslexic children need a larger print than non-dyslexic learners to achieve their reading speed. It concerns both the font size and number of words per line.

Font

The minimum size font should be 12 while the best one is 14-16.

Serif fonts such as Time New Roman can be too decorative. Sans serif fonts such as Arial, Comic Sans, Verdena are recommended but it often depends on personal taste. Tahoma or Century Gothic are further options of dyslexic-friendly font.

Lines

Lines should not be long: 60 to 70 characters or 12-15 words per line. We should avoid starting a sentence at the end of a line. It is recommended to keep 1.5 spacing between lines.

Italics

Italics are not dyslexic-friendly, so should be replaced by bold instead. Both underlining and italics make the text appear to run together.

In headings and titles we should avoid block letters. They are often harder to read so it is better to use bold in lower case.

Design

The design should be simple and consistent throughout the test. We should avoid narrow columns as used in newspapers, and pages cluttered with information.

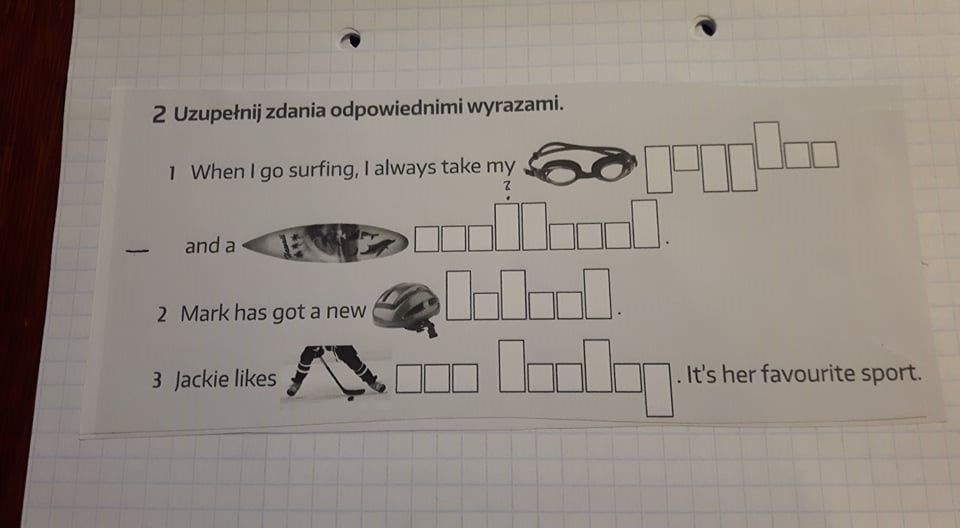

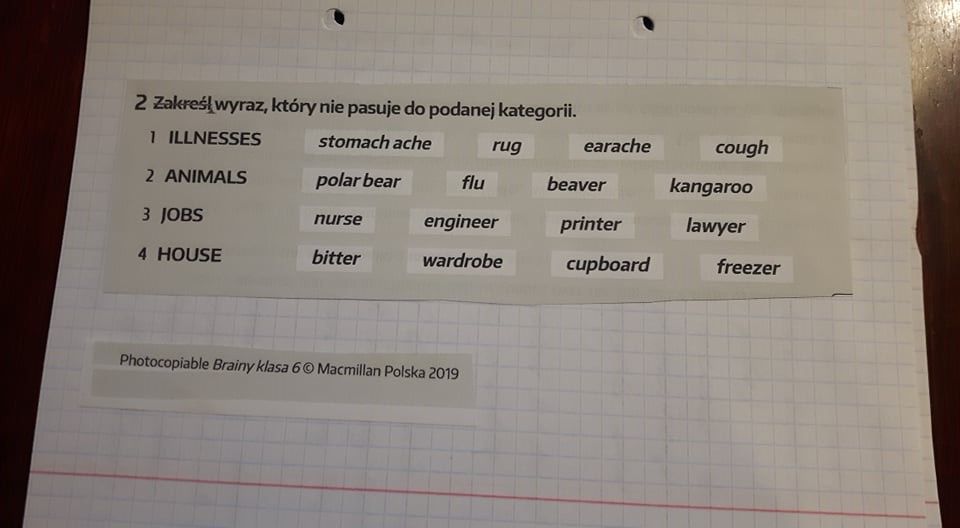

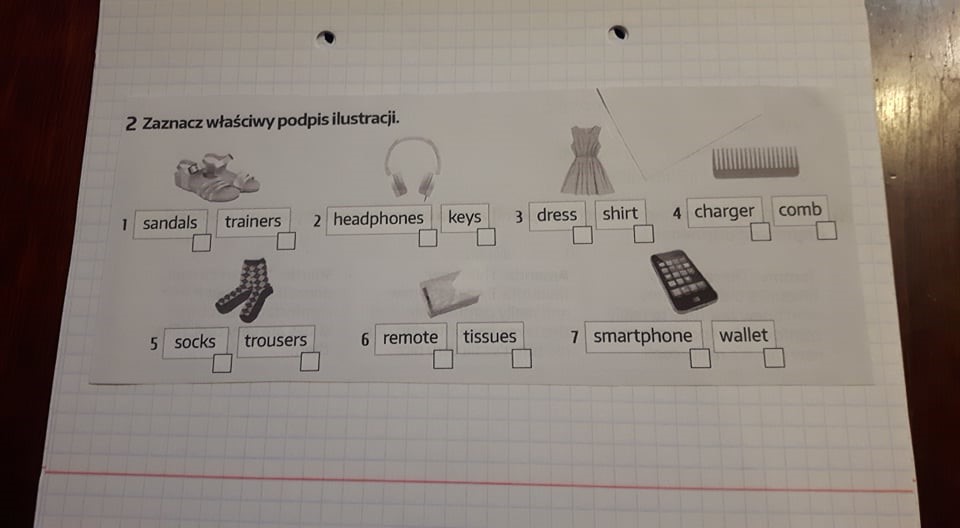

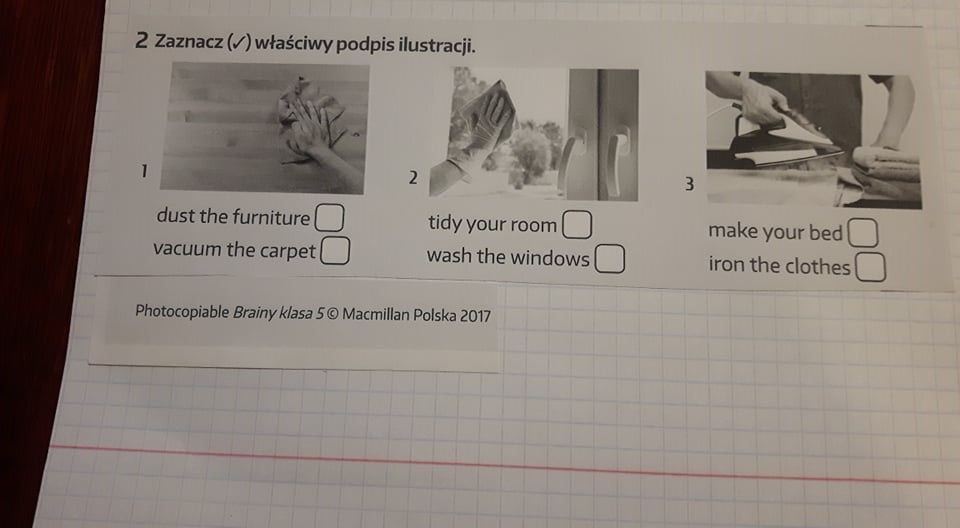

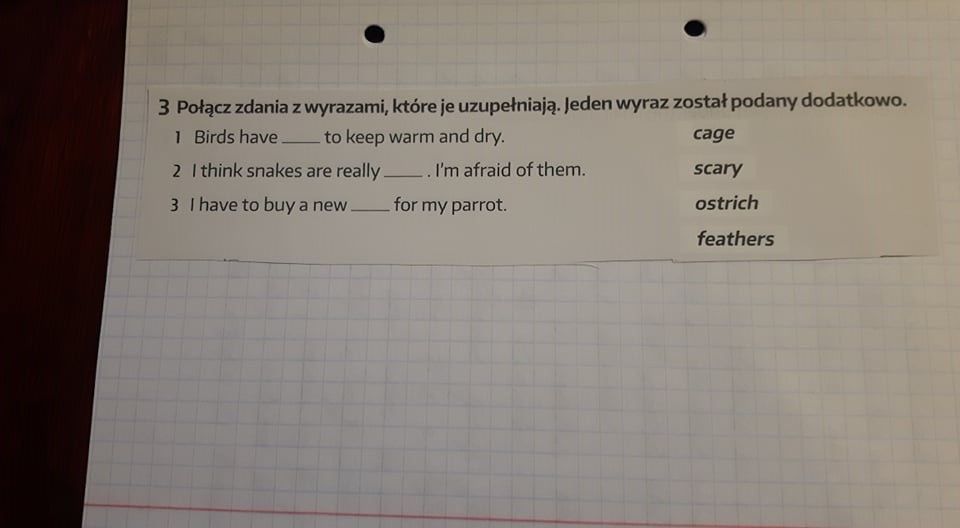

Most dyslexic students are visual thinkers so illustrations, pictures and cliparts can help them complete the tasks in the vocabulary parts of the test. Below are some examples of the dyslexia-friendly vocabulary tasks:

Brainy klasa 6, Macmillan Polska 2018

Paper

The paper given should be thick enough to prevent the other side showing through. Cream or other coloured paper is highly recommended because can reduce ‘glare’ and can be easier to read. Blue or grey ink is much better than black ink on white paper as can lead to eyestrain.

Instructions

While preparing tests, teachers must ensure that the instructions are simple, clear, do not require multiple tasks and are not ambiguous.

Example: The instruction ‘Choose the correct answer’ does not give information about how to select the correct answer: by underlining, crossing or circling.

‘ Circle the word which is the best for each sentence’ is much more precise.

If providing information or instructions, these should be displayed as numbered points, not bullet points as dyslexics can read the same piece of information twice or skip it entirely.

Examples

While preparing tests teachers should set suitable types of tasks: motivating, already experienced, appropriate and not causing difficulties.

Giving an example in every task is important and helpful. The students can understand or even guess what should be done in this task precisely.

Answer sheets and self- checking

Dyslexic learners find it difficult to proof read and edit their work. They also have difficulty in copying the answers onto the answer sheet, which very often results in inaccuracy. They definitely prefer writing or ticking the answers in the test rather than on the answer sheets.

Reading

As far as reading tasks are concerned, there are a lot of strategies that can be easily put into practice.

See instructions and examples below:

- Reading texts can be placed in boxes, especially if there are more than two, and all the post-reading tasks should be clear and placed below the boxes.

- Different coloured paragraphs can help students save time looking for the answers to the post–reading questions as the colour of the questions correlate with the intended paragraph.

|

Jim’s party. My name is Jim. It was my birthday on Saturday .I was eight. My three cousins came to see me in the morning, and in the afternoon I had a party at my house. Nine of my friends came. We played some games outside and then we went inside to have some lemonade. Then Mum said ’Go out in the garden again’. There was a clown there! He had square glasses, yellow hair and a long green beard. He told us a story about the jungle and drew some pictures. My friends and I laughed very loudly because he was very funny. My Mum was there, but I couldn’t see my dad. We went inside and had ice cream and cake in the kitchen. Then my friends went home. I helped Mum to clean the kitchen and then we sat down and had some more cake there. ‘Where’s Dad?’, I asked Mum. ‘In the living room’, she said. I went to find Dad, but I could only see the clown there. Then I looked at his face. He took off his funny beard, his hat and the glasses and smiled at me. It was Dad! ‘Thank you, Dad’, I said. ‘This was the best birthday party’.

|

A line between paragraphs should be left as it indicates a new part of the story.

- Dividing texts into smaller parts reduces the overwhelming challenge for the student. They can complete the post-reading tasks after each short section.

|

Jim’s party. My name is Jim. It was my birthday on Saturday .I was eight. My three cousins came to see me in the morning, and in the afternoon I had a party at my house. Nine of my friends came. We played some games outside and then we went inside to have some lemonade. Jim’s birthday was on ………………………………………. There were………………………………..of Jim’s friends at his birthday party. After the games, the children had ……………………………. in the house.

Then Mum said ’Go out in the garden again’. There was a clown there! He had square glasses, yellow hair and a long green beard. He told us a story about the jungle and drew some pictures. My friends and I laughed very loudly because he was very funny. My Mum was there, but I couldn’t see my dad. We went inside and had ice cream and cake in the kitchen. Then my friends went home. When the children went outside, they saw a …………………………..in the garden. The clown had green beard and wore some………………………..which were square. The …………………………….was about the jungle.

I helped Mum to clean the kitchen and then we sat down and had some more cake there. ‘Where’s Dad?’, I asked Mum. ‘In the living room’, she said. I went to find Dad, but I could only see the clown there. Then I looked at his face. He took off his funny beard, his hat and the glasses and smiled at me. It was Dad! ‘Thank you, Dad’, I said. ‘This was the best birthday party’. Jim and his mother ate………………………………..in the kitchen. The clown …………………………………..at Jim. The clown was Jim’s…………………………………………… |

4. In the reading tasks key words can be marked in bold to help dyslexic students focus their attention on the most important vocabulary and phrases to enable them to complete the post-reading questions correctly.

|

Hi Sonia, I’m writing to you from a film-making summer school. It’s located just outside London, close to a film studio. We actually spend some time working in the studio. It’s amazing. My friend had to talk me into going because at the beginning, I wasn’t all sure if it was a good idea. However, once I’d made up my mind, my parents actually agreed to pay for the whole course, so I didn’t need to touch any of my savings. I’m new to the world of film-making, so I’m doing the course for beginners. We’re learning some basic things about how to make a film. I enjoy nearly all of the classes. I’m focusing on the scriptwriting workshops, but most of the other teens here are just attending the acting lessons. It’s probably because they get to meet some real-life film stars. I’ve only been here for four days, but it’s been so much fun. I’m definitely coming next summer! Let me know how you’re spending your summer. ( based on the Brainy7 Macmillan test) |

5. Teachers can simplify the standard text and give dyslexic students the easier or shorter version.

6. Teachers can also allow more time for reading tasks or enlarge the text for easier reading

Grammar

Providing students with an example in grammar tasks is very important and helpful. Sometimes they cannot understand the instructions correctly, but following the example given he/ she can do what is expected of them. It is obvious that giving an example makes the task more visual and therefore easier to deal with.

It might be a good option to write grammar task instructions in L1 or in both languages to make them more understandable for the students.

We should avoid ‘Correct the mistakes’ tasks as most dyslexic students cannot even see their own mistakes so there is a great probability that they will leave that task undone.

In multiple-choice tests of choosing up to 4 options, the best suggestion is to reduce the number of alternative answers to 3 or even 2, as too many distractors can be confusing and complicated.

Gaining more knowledge and crucial information about dyslexia, teachers will be able to prepare dyslexia-friendly tests.

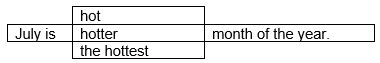

Here are some examples.

Standard test

- Translate into English

July is usually (najcieplejszym)…………………………………….month of the year.

Dyslexia-friendly variation

1a. Choose the correct word/s and colour it/ them in the box

Put the words in the correct order to make a sentence.Standard test:

the hottest, year, month, is, July, of the

Dyslexia friendly variation:

2a. Put in the missing words. Some letters are given.

July is _ _ e_ _ _ _ e _ _month of the year.

Assessment and evaluation

When a standard/ basic test is ready teachers should think carefully which parts of the test are ‘must haves’ and which are ‘extras’. The ‘extras’ can be omitted or eliminated to make the test shorter for those with special educational needs.

Generally, teachers may find it difficult to evaluate the accuracy of dyslexic learners because in many cases it is not clear enough whether a mistake is made because of the reading, spelling or writing difficulties due to the fact that the student doesn’t understand or hasn’t comprehended a rule.

It is much better to use a formative assessment rather than a summative one. In a formative assessment the teacher gives feedback to the students with difficulties, so that they can improve their learning skills.

Good testing practices and formative assessment can benefit dyslexic students a great deal, motivate them, give them satisfaction and boost their self-confidence.

References

Dyslexia for teachers of English as a foreign language, Teacher’s Booklet, unit 10, The assessment of dyslexic language learners, DysTEFL

Kormos,J., Smith,A.M. ( 2012) Teaching languages to learners with specific learning difficulties

Power,K., Forsyth, K.I. ( 2017) The illustrated guide to dyslexia and its amazing people, Jessica Kinsley Publishers

Reid, G. ( 2005) Dysleksja, K.E.Liber

Please check the Special Needs and Inclusive Learning course at Pilgrims website.

The Art of Writing Tests for Dyslexic Students

Barbara Skrok, Poland