Impressive First Class Meeting: Jigsaw Technique Oriented

Siti Mina Tamah is a full-timer at the English Department of Widya Mandala Catholic University, Surabaya, Indonesia. She has great interest in language teaching methods. Her current research topics are related to cooperative learning and assessment.

Introduction

An English class of which the topic was “Greetings and Partings” was just over. It was the end of the school day. The students were joyful to tidy the class as it was also time to go home. At home these two questions might appear: “What has the teacher taught you?” and “What have you learnt?” The answer is undeniably the same: “Greetings and Partings”; the reply will to a certain extent make the respective teacher happy. Well, what about the surprising answer “No idea.” or “I forget it.” The reason of such an unexpected reply is that the class is not yet engaging. Harmer (2007) argues the less engaging the students are, the less likely they remember what they encounter in class.

Literature on teaching method has long upheld the teaching paradigm which is in favor of the notion that knowledge is not transferred but that knowledge is constructed (Kaplan, 2002; Williams & Burden, 1997). Nobody can plant the knowledge into the students; the students are to do the knowledge planting themselves (Sumarsono, 2004). Since then it is vital for teachers to transform their traditional class into a ‘constructive’ class (Tamah, 2011) or to abandon their spoon-feeding technique (Tamah, 2013). Teachers are challenged with the constructivist thinking of how to involve students in relevant tasks so that the students are really engaged in the classroom. This constructivist thinking is refined more by the presence of another affective-oriented perspective that has gained increasing prominence in language teaching. Harmer (1994, p. 35) puts it: “… language teaching is not just about teaching language, it is also helping students to develop themselves as people.” Teaching should center on students as a ‘whole person’ emphasizing the ‘emotional being’ of students (Rogers, 1977 cited in Brown, 2007, p. 97). Interpersonal relationship has been the core element.

Classroom instruction should provide room for student engagement. This idea is in line with the humanistic approach which put emphasis on how students learn. Harmer (1994) reminds teachers of two primary tasks: to count on the experience of the students and also to ponder the essence of the development of students’ personality and the encouragement of positive feelings.

As construction of knowledge is considered as a social and dialogical process, student participation or student classroom engagement is significant. Making use of Jigsaw technique is one of the paramount means to involve more student participation.

The word ‘technique’ in Jigsaw technique is occasionally used interchangeably with other words like ‘activity’, ‘approach’, ‘design’, ‘method’, ‘process’, ‘procedure’ (Tamah, 2011). In this paper, Jigsaw is used interchangeably with Jigsaw technique.

Jigsaw, which is initially introduced by Aronson in 1978, is one of the earliest documented cooperative learning techniques (Slavin, 1994). It is commonly characterized by students’ working in two teams: home teams and expert teams. A student is put firstly in the expert team whose members are those having the same task and materials for discussion. At the end of the expert team discussion, the student becomes, as the name implies, the expert of a particular material. The student is then put in the home team to share his or her expertise with the other home team members. It is in the home team that the students are expected to learn the whole materials. Aronson (2005) puts it: “This “cooperation by design” facilitates interaction among all students in the class, leading them to value each other as contributors to their common task.”

In Jigsaw technique, students move from the expert team to the home team setting. The movement of the students working in groups by using Jigsaw technique will justly mean the abandonment of traditional class setting where students work in a tidy row facing the teacher. This swift from a traditional class to a moveable class will reassuringly mean the endeavor toward a more active class. Comparing between a traditional class and a moveable class, McCaughey (2018) suggests that teachers keep the moveable class for more active and healthful class. The idea that students get out of their seats at least once per lesson to be involved in more group work is in line with the Jigsaw implementation.

Referring to Lefstein and Snell (2014), Sedlaceka and Sedova (2017) further put forward that since students learn best through active participation, a rich and stimulating condition should be created. The increased student engagement in classroom communication will lead to better learning results.

Open discussion which is established in a class will bring about the increasing number of students who speak and the increasing number of high-quality student utterances as well. Sedlacek and Sedova (2017) further argue that discussion which is open stimulates student engagement more than other communication forms like the prevailing IRF pattern of teacher’s initiation, student’ response, and teacher’s feedback.

This Humanistic approach highlights “the development of human values, growth in self-awareness and in the understanding of others, sensitivity to human feelings and emotions, and active student involvement in learning and in the way human learning takes place” (Richards, 2002, p.23).

Focusing on first class meeting

The first class meeting, as its name suggest, is solely the very first session of the classroom instruction. It is the first meeting of a course or a class in a new academic year. It is the session when teachers taking humanistic approach are obliged to establish interpersonal relationship to touch the affective domain of teaching.

The very first meeting in which a teacher meets a group of student strangers produces both excitement and anxiety for students as well as the teacher (Mc.Keachie, 1994). If we have prepared well before entering the class – preparing the syllabus covering the preparation of objectives, materials, methods, and evaluation, we are in good shape. The preparation beforehand will increase our self-confidence. On the other side, the students will be pleased that the instruction is under control; they are glad to have a well-prepared class.

Students attending the first class want to know what the class is all about and what sort of person the teacher is. The first class is worth considering since our class is not the students’ only class. They come to us from other classes. The first class meeting is worth spending on special activities to smoothen the chaos. McKeachie (1994, p. 22) more particularly puts it, “The first few minutes need to help this varied group shift their thought and feelings to you and your subject.”

It is therefore arguable to say that the first class meeting is encouragingly tough to prepare. We need to think wisely about what to do to engage students from the very class meeting to win their heart.

Before the class period begins, we can make use of the time by communicating non-verbally by such things as arranging the seats in a circle and putting our name on the board. Another way to kill the time before the bell of the first class meeting rings is chatting with early arrivals – students who come early. Finocchiaro (1974) claims that teachers transmit not only knowledge but also more specifically enthusiasm, desire, and interest in students as human beings.

After introducing himself or herself briefly, the teacher can form small groups of 3-4 students. When small groups are formed, ice breaking activities can be carried out. Tamah (2017) presented step-by-step procedures of two types of activities: a cocktail party and two truths one lie.

The small groups formed are to be named, and the group naming should be meaningful. As character building is widely recommended to be inserted in all lessons – not only confined to a special class of character building, adjectives to show good characters can be used in our English class also. Important values for quality life can be introduced indirectly. Here are ten adjectives that can be chosen for group naming: (1) Enthusiastic, (2) Caring, (3) Honest, (4) Humble, (5) Loyal, (6) Polite, (7) Reliable, (8) Sincere, (9) Tolerant, and (10) Wise.

After group naming, the teacher can continue with classroom rule establishment which is an issue of classroom management. As pointed out by Orlich et al. (1985) the very first day of school is critical in the establishment of standards. Carrying out the establishment of a code can be performed through discussion to discover some kind of conducts. The discussion of code establishment with adult students is different from the one with younger students. Harmer (1994, p. 249) puts it, “It is worth emphasizing that the establishment of a code will be done differently, depending the age of the students. With adults you may discuss the norms of behavior that should apply, whereas with younger children you may be a bit more dictatorial …” In this establishment of a code, the key is, Finocchiaro (1968) claims, that teachers have to make sure students understand exactly the forms of conduct or behavior expected of them.

The syllabus or course outline sharing usually ends the class. It is certainly useful for students to know what the class is all about and how the class objective will be attained. It provides a roadmap for students to achieve class objectives.

Setting the impressive first class meeting, this paper will center on making use of Jigsaw technique for group naming and classroom rule establishment. This is at the same time expected to be the enactment of ice-breaking activities. Yes, the iceberg is there blocking and it is essential that the iceberg coming between the students and the teacher be shattered. A corresponding idea of Brown (2007, p. 159) is worth revealing: ‘walls of inhibition’ inside students is lowered when the teachers ‘provide cocktails’ or ‘prescribe tranquilizers’.

Procedure: Group naming - Jigsaw-oriented

General information

The adjectives determined to be used in this particular exemplification cover Caring, Honest, Loyal, and Polite since an example of a 16-student class will be taken to provide procedural steps.

Four 4-student groups are formed. They are initially called as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3, and Group 4. After the activity is completed, they are named Caring, Honest, Loyal, and Polite.

Materials preparation

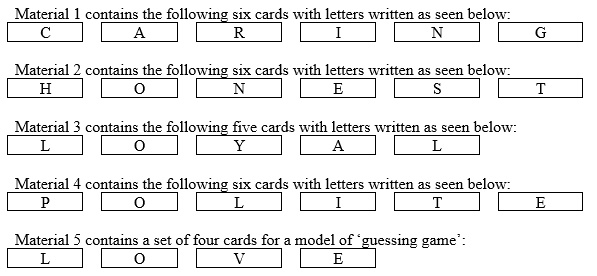

Five kinds of materials are prepared for a guessing game session. Material 1 (inside Envelope 1) is for Expert Team 1; Material 2 (inside Envelope 2) is for Expert Team 2; Material 3 (inside Envelope 3) is for Expert Team 3; Material 4 (inside Envelope 4) is for Expert Team 4. Material 5 (inside Envelope 5) is for a model of guessing game.

Four kinds of spare materials are prepared. They are exactly the same as Materials 1-4. They will be used after the guessing game session – for unscrambling activity. The spare materials are prepared for the comfort of group discussion. Instead of one set of materials, it is wiser to have two sets of materials for a 4-student group.

Spare Material 1 contains six cards as seen in Material 1. Spare Materials 2, 3, and 4 also contains the same cards as in Materials 2, 3, and 4.

Final sentence to close Materials Preparation: It is prudent to laminate the cards in each Material. The durable cards can be reused in every first meeting class in future academic year

Classroom implementation

- After simple grouping, tell students that they are now in their home teams. Inform that members of Group 1 are labelled S1.1, S1.2, S1.3, and S1.4. Members of Group 2 include S2.1, S2.2, S2.3, and S2.4. Members of Group 3 are S3.1, S3.2, S3.3, and S3.4. Members of Group 4 are labelled S4.1, S4.2, S4.3, and S4.4. Make sure each student in each group is then labelled.

- Tell the students to form their expert teams. Expert Team 1 consists of S1.1, S2.1, S3.1, S4.1. Expert Team 2 consists of S1.2, S2.2, S3.2, and S4.2. Expert Team 3 consists of S1.3, S2.3, S3.3, and S4.3. The rest S1.4, S2.4, S3.4, and S4.4 belong to Expert Team 4. In simple terms: All 1 get together as one expert team. Likewise, All 2, All 3, and All 4 get together. Four expert teams are then formed.

- Provide expert teams with an example of a group activity: a guessing game. Choose one expert team. Three students in the chosen expert team are sincerely requested to be in front of the class facing against the whiteboard (they are facing all the other classmates). Take Material 5 (Take out the four cards inside Envelope 5). Put them face down on a table. Scramble the cards.

- Start illustrating to the three students: The cards inside the envelope are now on the table. As you can see, all cards are face down. I take one card and OK, I will help you to get the letter. I will give clues, and you guess. Write the letter which appears on the card chosen. Write it on the whiteboard so that all other students are engaged – they can see it in order that they can follow the exemplification more easily.

- As the card chosen has ‘O’, continue illustrating: The opposite of INSIDE. What is it? When one, or two, or three students respond OUTSIDE, say: Take the initial. The initial of the word you just said. When one, or two, or three students respond ‘O’, say while revealing the card with the letter O: Yes, that is the one. ‘O’ is guessed. Ok, I now put this card face up because it is guessed already. We use any clues to help our friends get the letter. All right, another example. I take another card and …

- As the card chosen has ‘V’, continue illustrating: I love you bla bla bla much. Showing degree. What is it? Or Well, this is a letter somewhere the end of Roman alphabet. When we double this letter, it becomes ‘double you’ ‘W’. What letter is it? When one, or two, or three students respond VERY, say: Take the initial. The initial of the word you just said. When one, or two, or three students respond ‘V’, say: Yes, that is the one. ‘V’. ‘V’ is guessed. I put the card face up now. OK, I hope you get it. Guessing game. Guessing the letters. Use clues to assist the group members to get the letters. Do it in turns. When all cards are face up already, shout BINGO. I will give you another set of cards.

- Distribute Material 1 to Expert Team 1. Distribute Materials 2, 3, and 4 to Expert Teams 2, 3, and 4 respectively.

- Ask them to enjoy the guessing game activity. Circulate and facilitate when necessary.

- When the expert team completes the activity, or when BINGO is heard, give the spare materials. Spare Materials 1, 2, 3, and 4 are for Expert Teams 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively. Have the cards in each Spare Material taken out and they are face up directly. The four-student teams are now paired and each pair gets a set of cards to unscramble. Say: OK, you form pairs now and each pair will have a set of cards to unscramble. When they are unscrambled, they can be a word, a good word in English. Find out what the word is.

- Circulate among expert teams making sure that all expert teams get the words. Expert Team 1 will have ‘Caring’. Expert Teams 2, 3, and 4 will have ‘Honest’, ‘Loyal’, and ‘Polite’. Ensure that only Expert Team 1 knows ‘Caring’. This is not to be revealed to the other expert teams.

- Ask each team to find ways to illustrate the word. When they go back to their home team, they are expected to be able to assist their home team members to guess the word. Students of junior high school can be assisted with some guides to be written on the board: “This character starts with ‘__’ and ends with ‘__’. When we have this character, we ____________. In our language Bahasa Indonesia, it is ______”

- Give an example for WISE: This character starts with ‘W’ and ends with ‘E’. When we have this character, we are like Judge Bao. Remember the serial film some time ago? We have good judgements based on deep understanding of life. In our language Bahasa Indonesia, it is “bijaksana”.

- Dismiss the expert teams and form the home teams. In each home team there are four students bringing a different word each. Ask them to do the task of Home Team (guessing a word) in turns. Each shares his/her expertise.

- When all four words – all four good characters – are revealed, enforce the good characters for the whole class. Educating issue of character building is touched upon. The class is not just teaching but also educating.

- Close the group naming activity by saying: Well, we have a nice class here. We have good people. We have Caring Group [pointing to Group 1]. We have Honest Group [pointing to Group 2]. We have Loyal Group [pointing to Group 3], and we have Polite Group [pointing to Group 4]. Let us keep these good characters in our class.

Procedure: Classroom rules establishment - Jigsaw-oriented

General information

A set of classroom rules will be revealed to the students. Unlike in the traditional way, the students are exposed to the classroom rules not from listening passively to the teacher but they get the rules from actively engaging themselves in a Jigsaw activity.

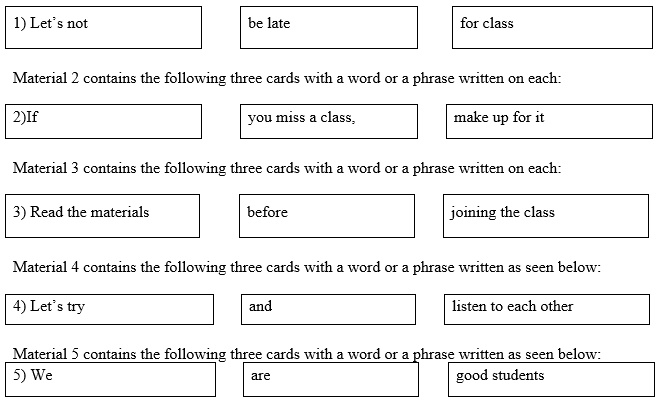

The classroom rules prepared say: 1) Let’s not be late for class, 2) If you miss a class, make up for it, 3) read the materials before joining the class, 4) let’s try and listen to each other.

A paper of Tamah (2013) has presented the use of Jigsaw technique to reveal classroom rules. This section is similarly presented to have the same purpose; nevertheless, this paper will reveal a modified design to suit younger learners. The materials are a bit differently prepared as they will be presented to less adult learners. In the previous paper, the sentences which are written in full are given to be discussed in the expert team. Here the group task is made easier – the sentences are put into phrases and to be unscrambled. The group names in a 16-student class include Caring, Honest, Loyal, and Polite.

Materials preparation

Five kinds of materials are prepared for the group task in the expert teams (first dictation activity and then rearrangement of the words dictated). Material 1 (inside Envelope 1) is for Expert Team 1; Material 2 (inside Envelope 2) is for Expert Team 2; Material 3 (inside Envelope 3) is for Expert Team 3; Material 4 (inside Envelope 4) is for Expert Team 4. Material 5 (inside Envelope 5) is for a model of dictation activity followed by rearrangement activity.

Material 1 contains the following three cards with a word or a phrase written on each:

Classroom implementation:

- Confirm that students are now in their home teams of Caring, Honest, Loyal, and Polite. Inform that members of Caring Group are labelled C1, C2, C3, and C4. Members of Honest Group include H1, H2, H3, and H4. Members of Loyal Group 3 are L1, L2, L3, and L4. Members of Polite Group are labelled P1, P2, P3, and P4. Make sure each student in each group is then labelled.

- Tell the students to form their expert teams. Expert Team 1 consists of C1, H1, L1, P1. Expert Team 2 consists of C2, H2, L2, and P2. Expert Team 3 consists of C3, H3, L3, and P3. The rest C4, H4, L4, and P4 belong to Expert Team 4.

- Provide expert teams with an example of a group activity: dictation. Choose one expert team. Three students in the chosen expert team are sincerely requested to be a model group. Take Material 5 (Take out the four cards inside Envelope 5). Put them face down on a table. Scramble the cards.

- Start illustrating to the three students: The cards inside the envelope are now on the table. All cards are face down. I take one card and I will write first. Now I dictate it to you, and you all write (Each student writes including the one dictating).

- Distribute Material 1 to Expert Team 1. Distribute Materials 2, 3, and 4 to Expert Teams 2, 3, and 4.

- Ask them to do the dictation activity in turns. In Expert Team 1 for instance, after C1 takes a card and writes and dictates to H1, L1, and P1, the turn goes to H1 to do similarly: choosing a card, writing, and dictating. Circulate and facilitate when necessary. As only three cards are available, only three students will be the ones getting the opportunity to choose a card.

- When the expert team completes the dictation activity, ask them to rearrange the dictated words. Say: Try to rearrange the words. Find the expected sentence, and make sure you know the meaning of the sentence.

- Write on the board: Who says the sentence? When? What for/Why? (This is expected to include higher order thinking skills, popularly shortened as HOTS). Ask each expert team to discuss it – the classroom rule discussion. This is not to be revealed to the other expert teams. Circulate making sure that all expert teams get and understand the sentence.

- Ask each team to find ways to negate the sentence (make a contradictory sentence). When they go back to their home team, they say the meaningfully wrong sentence for a classroom rule and ask their home team members to correct it.

1) “Let’s not be late for class” can be easily converted into “Let’s be late for class”.

2) “If you miss a class, make up for it” can be converted into “If you are absent from a class, just do nothing to catch up. “

3) “Read the materials before joining the class” can be converted into “Come to class without reading the materials.”

4) “Let’s try and listen to each other” can be converted into “Let’s pay no attention to our friends, or Let’s pay attention to our teacher only.”

- Dismiss the expert teams and ask them to go back to their home teams. In each home team there are four students bringing a different sentence each. In turns the students read the sentence to be corrected by the other members. A set of classroom rules are discussed in the home teams.

- When all four sentences – all four classroom rules – are revealed, some time can be spent to have other additional rules to discuss.

- Close the classroom rule establishment by wrapping up the rules.

Conclusion

This paper has provided new ways of communicating knowledge within a game-like environment by uplifting Jigsaw technique – a technique of cooperative learning which is broadly a student-centered mode of teaching. This is in fact an attempt to realize the notion that productive student engagement in classroom instruction will yield quality learning. This corresponds with the fundamental insight of humanistic approach which runs an awareness of concepts of maintaining low affective filter in students’ learning so that the learning is fostered – the dream of all teachers.

References

Aronson, E. (2005, 2010). Jigsaw Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.jigsaw.org 2000-2005; 2000-2010

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). New York: Pearson Education.

Finocchiaro, M. (1968

Finocchiaro, M. (1974). English as a Second Language: From theory to practice. New York: Regents Publishing Company, Inc.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of language English language teaching (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Kaplan, E. (2002). Constructivism as a Theory. Retrieved from http://online.sfsu.edu/~foreman/itec800/finalprojects/eitankaplan/pages/classroom

McCaughey, K. (2018). The moveable class: How to class-manage for more active and healthful lessons. English Teaching Forum, 56(1), 2-13.

McKeachie, W. J. (1994). Teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company.

Orlich, D. C., Harder, R. J., Callahan, R. C., Kravas, C. H., Kauchak, D. P., Pendergrass, R.A., Keogh, A. J., & Hellene, D. I. (1985). Teaching strategies: A guide to better instruction. (2nd ed.). Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company.

Richards, J. C. (2002). Theories of teaching in language teaching In J. C. Richards & W. Renandya (Eds.). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. pp. 19-25. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sedlacek, M. & Sedova, K. (2017). How many are talking? The role of collectivity in dialogic teaching. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 99–108

Slavin, R. E. (1994). A practical guide to Cooperative Learning. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Sumarsono. (2004). Otonomi pendidikan. Jakarta: Komisi Pendidikan KWI.

Tamah, S. M. (2011). Student interaction in the implementation of the Jigsaw technique in language teaching. Dissertation. Groningen University. https://www.rug.nl/ research/portal/files/2541505/thesis.pdf

Tamah, S. M. (2013). Introducing classroom rules using the Jigsaw technique: A model. English Edu Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(1), 34-41. http://repository. uksw.edu/handle/123456789/3480

Please check the How to Motivate Your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Lesson Ideas: Discussing Religious Values in English Classrooms, In an Intercultural Way

Fenty Lidya Siregar, IndonesiaTo-Too-Two, Price-Prize, See-Sea

Johanna B. S. Pantow, IndonesiaBilingual Short Story for Translation Class

Junaedi Setiyono, Indonesia“Where is Komodo?”: Student-tailored E-books for Indonesian EFL Learners

Ju Seong Lee, Hong Kong SAR, China;Nicole Lam, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaA Private Reading Lesson: A Story with Cia

Sandi Ferdiansyah, IndonesiaImpressive First Class Meeting: Jigsaw Technique Oriented

Siti Mina Tamah, Indonesia“Switching” to Critical Reading: Reading within the Four Resources Framework

Endang Setyaningsih, IndonesiaTeaching Students on How to Summarize Journal Articles

Dyah Sunggingwati, Indonesia