- Home

- Various Articles

- Boosting Employees’ Intercultural Job Performance with a Flexible Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) Mindset as Agile Learning Companions

Boosting Employees’ Intercultural Job Performance with a Flexible Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) Mindset as Agile Learning Companions

After working in the export department of a beverage group, Katrin Lichterfeld (MA -CertIBET - authorized trainer/examiner for ‘Intercultural Competence in English’) has been working as a freelance in-company trainer (communication skills/intercultural competence) in Germany for nearly two decades. She participated in the EU-funded ENRICH project “English as a Lingua Franca practices for inclusive multilingual classrooms”. Email: info@communicationlights.de

Introduction

How to describe a world that seems to be changing faster than ever before. Even when using the acronym VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity), which was originally developed by the US military in the 1990s, many executives in the business world show a tendency of offering only one highly general solution for all the four of its components such as ‘innovate’, ‘be creative’, ‘be flexible’, or ‘listen more’. Other researchers speak about an enormous paradigm shift, which has even further been disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. How will the consequences look like for corporate learning and training in general and for corporate language and communication training in particular? What about the impact of English as number one medium of communication on employees’ confidence when having to speak up in virtual formats? How do corporate learning contexts look like in some German companies? How could a useful combination of structured formal training and self-directed informal learning highly boost employees’ intrinsic motivation and self-reflection? How could this be complemented by BE practitioners as agile learning companions supporting employees to adapt with a Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) mindset and inclusive BELF practices? Although this article focuses on the corporate context, most of the aspects are relevant for and transferable to many other areas of learning and communicating in English.

Digital transformation of corporate learning

BE practitioners in corporate contexts, who would like to keep having or increase their impact on their course participants’ lives, need to focus more on their cooperation with HR managers or any other stakeholders involved they may have access to (Bowie 2020). Focusing on the employees’ performance to get their jobs done in a better and faster way will only be possible after taking the HR manager’s perspective and getting an idea of the big picture. How have the challenges of a VUCA world had an impact on organizational and individual performance, on working and learning, on all the stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities, and on the company culture? Bennett/Lemoine (2014) are fully aware that when analysing a situation, the components of VUCA are often intertwined. Nonetheless, they suggest developing the discipline to look at the components on their own and how they are combined to both find adequate solutions and avoid frustration.

Table 1. Distinctions within the VUCA framework

|

|

What it is |

How to effectively address it |

|

Volatility |

Relatively unstable change: information is available, and the situation is understandable, but change is frequent and sometimes unpredictable. |

Agility is key to coping with volatility. Resources should be aggressively directed toward building slack and creating the potential for future flexibility. |

|

Uncertainty |

A lack of knowledge as to whether an event will have meaningful ramifications; cause and effect are understood, but it is unknown if an event will create significant change. |

Information is critical to reducing uncertainty. Firms should move beyond existing information sources to both gather new data and consider it from new perspectives. |

|

Complexity |

Many interconnected parts forming an elaborate network of information and procedures; often multiform and convoluted, but not necessarily involving change. |

Restructuring internal company operations to match the external complexity is the most effective and efficient way to address it. Firms should attempt to ‘match’ their own operations and processes to mirror environmental complexities. |

|

Ambiguity |

A lack of knowledge as to ‘the basic rules of the game’; cause and effect are not understood and there is no precedent for making predictions as to what to expect. |

Experimentation is necessary for reducing ambiguity. Only through intelligent experimentation can firm leaders determine what strategies are and are not beneficial in situations where the former rules of business no longer apply. |

Source: Adapted from Bennett/Lemoine (2014)

The term volatility often stands for the general definition of VUCA that is used in the business world such as describing an “unstable” or “unpredictable” situation. Agility is supposed to solve this volatile situation by analyzing the factors of fluctuation and the likelihood of possible causes and effects. In an uncertain situation, however, there is a lack of knowledge, but there may be no change at all. The process of gathering information has to be adapted by moving beyond existing internal or external networks. Addressing a complex situation with stockpiling (agility) or new networks (information) could cause the allocation of resources in inadequate locations or result in an information overload. Thus, restructuring is the most efficient way to adapt to environmental complexity. In the case of ambiguous situations, there is hardly any historical precedent concerning causes or effects. The solutions that may work for the other three elements may only make sense when experimenting with them and taking risks. Although the elements of VUCA may not always appear clearly separated, looking for solutions in an individual and a combined way will help taking appropriate decisions, especially with regard to the enormous need for adapting skills.

Reskilling and upskilling in a globalized world

According to the World Economic Forum (2020), about 40% of core skills will change for people keeping their current jobs, while reskilling and upskilling will be crucial for 50% of the employees in unprecedented numbers. Moreover, 85 million jobs will be moved from humans to machines, and nearly 100 million jobs will start to exist as a new version of labour division between humans, machines, and algorithms. Since the first report in 2016, critical thinking and problem-solving skills have been in top positions of the skill ranking. In 2020, skills in self-management (active learning and learning strategies in second position, resilience, stress tolerance and flexibility) emerged for the first time. Furthermore, Gartner (2020) highlights that the Covid-19 pandemic has “fast-forwarded the digital adoption by 5 years”. Digital skills have become essential across nearly all organizational functions and have to be combined with soft skills to achieve any form of successful transformation. Korhut (2020) compares this paradigm shift to the move from the agricultural to the industrial society about 100 years ago:

“There must be an industrial revolution in education, in which educational science and the ingenuity of education technology combine to modernize the grossly inefficient and clumsy procedures of conventional education.” (Sidney L. Pressey, 1924)

The OECD/Asia Society (2018) ask “how to prepare students for the complexity of a global society?” and suggest four key aspects together with the Center for Global Education:

- investigate the world beyond their immediate environment by examining issues of local, global, and cultural significance

- recognize, understand, and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others

- communicate ideas effectively with diverse audiences by engaging in open, appropriate, and effective interactions across cultures

- take action for collective well-being and sustainable development both locally and globally.

English as a global language at work

Additionally, the Cambridge English/QS Global Employer Survey (2016) highlights that “wherever you are in the world, English is the language of international business, science and research”. No other language has ever been as important as English. About 80% of academic journals is written in English and more than 85% of employees in international organisations make us of English in their working life. Using English as company language may even have a negative impact on employee morale and create an unhealthy divide between so-called native and non-native speakers. In spite of such an accelerated need for English at work, this survey is the first to provide in-depth research of English language skills that are required by employers (5,373) at work across different company sizes, industries (20) and countries (38) around the world. The key findings of the survey are that there is a skills gap of at least 40% regardless of the industry or the company size and in spite of huge and increasing investments in educational and in-company programmes. The biggest gaps of required English skills can be found in internal-facing roles (Human Resources, Accounting and Finance, Production and Logistics). Middle and top management have only a 25% skills gap. The survey reveals that this English skill gap will put further pressure on employees’ job performance, especially for so-called non-native speakers at lower hierarchical levels or with less intercultural (business) experience.

Employees and other stakeholders may not be aware of the global uses and users of English. Lichterfeld (2019) illustrates with Kachru’s “Three circles of English” from 1983 that the number of English users in the “expanding circle countries”, where English is still mostly taught as a foreign language, has enormously been increasing. According to Graddol (2006), about 80% of international communication already takes place without any so-called native speaker being present and the authors of the QS Global Employers Survey (2016) estimate that 1.5 billion people are currently learning English worldwide and China is the fastest growing and largest market (400 million people). By 2020, the number of people speaking English in China was supposed to be higher than the number of all the English native speakers worldwide together.

What does this ratio tell us about the ownership of English? What consequences will these changed uses and users of English have concerning the still dominating role models of native speakers from the UK or the USA and Anglo-American cultural norms? Although language and culture are inseparably connected, many employees and other stakeholders still think that above all linguistic resources like perfect grammar, correct vocabulary, sounding like a so-called native speaker and speaking fluently play a key role when communicating across cultures. Employees will have to become aware of their own and others’ rich linguistic and cultural diversity and will have to develop appropriate intercultural competence combined with a flexible mindset and agile learning to deal with the challenges of a VUCA world.

Agile Learning in a corporate context

Gartner (2020) stresses that the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic have provided evidence for what many employers already knew beforehand: “Legacy ways of working are outdated”. Thus, companies will have to embed agile work design to break roles and projects into skills. If the required skills cannot be provided internally or by departmental talent swap, freelancers like BE practitioners will be able to add value. Human resources will get a new role as digital change agent. For some years, employers have already been adapting in-company training and on-boarding programs to reduced attention spans (Techademy 2021). The term microlearning was first mentioned by Hector Correra in 1963. Due to the fast spread of mobile devices and the just-in-time approach from the Japanese automotive production, many consider the ‘bite-sized’ format as an important part of a company’s learning and development strategy. Most of the microlearning activities follow the recommendations of being accessible, holistic, interoperable, story-based, task-based, and timely. They could work as an ideal area for BE practitioners to contribute learning possibilities to a corporate learning ecosystem, because they are a cost-effective and smart learning tool, which increase learning transfer based on desired business outcomes and support self-directed learning.

Giddings (2015) clarifies that self-directed learning “has been one of the fastest-growing and most-researched areas“ in the past decades. After a paradigm shift to the constructivist approach, it has been considered as an essential skill for the 21st century and for life-long learning. Nonetheless, Graf (2019) explains that self-directed and life-long learning means handing over responsibility to the employee and taking over responsibility as an employee at the same time. These topics have mostly been dealt with in a rather superficial way in spite of Charles Jennings’s (2013) highly popular learning & development framework: 70:20:10. While only 10% of learning takes plays in formal training settings, 20% is provided by informal learning (exchange of information and learning in networks or communities of practice) and an overwhelmingly high percentage figure of 70% comes from on-the-job experience. This framework highlights the importance of self-directed and life-long learning as well. Graf et al. (2019) add that apart from defining how (self-directed learning), with whom (social learning) or where (workplace learning) you learn, there are other expressions or buzzwords that need further explanation. “Learning 4.0” stands for the interplay of the learner and digital tools to guarantee an increase in performance by efficient learning. It refers to “Industry 4.0” and the idea of increasing efficiency based on digital and technological networks. “New Learning” is closely related to the concept of “New Work” and its criticism of capitalism. While it focuses on experienced meaningfulness, self-realization, and development of potentials, it often takes place in a learning community too. Although there are a lot of overlapping areas with “agile learning”, not all activities or jobs may allow self-determination or self-development. Moreover, the focus is more on the learning individual employee, whereas “agile learning” describes adaptability at an individual and organizational level. Graf (2019) defines it as follows:

“Agile learning is derived from agile work and aims at the lifelong adaptability and innovative ability of people and organizations. Agile learning processes are characterized by short, clearly structured processes with simultaneous flexibility and individualization of the content (e.g., WOL, Bar camp). This approach is characterized by goal orientation, collaboration, self-regulation, and dynamics. In a broader sense, agile learning requires a suitable mindset (self-efficacy and ability to develop), skills (e.g., learning skills) and a suitable culture of mistakes and learning.”

Graf et al. (2019) explain that “agile work” started as a movement based on the “agile manifesto” in 2001. According to its four values, agile learning is characterized by four principles, which originate in a need for adapting to fast change: focus on employee’s needs, shift from delivery to co-creation, from content to context, and from training satisfaction to business impact. The most frequent model of agile learning is based on SCRUM.

Agile learning – redefining roles and learning culture

As a consequence of this paradigm shift the HR purpose shifts from input & output to outcome, from supply-oriented to demand-oriented personnel development, and the “ownership of learning” is supposed to move to the employee. Thus, the roles of all the stakeholders involved will have to be redefined. HR managers need to be the first to start this journey towards agile learning as role models of self-directed learning. Together with the respective supervisors, they need to demonstrate that agile learning has a high value within the company and need to support the employees as their learning companions. Even when HR is willing to hand over responsibility to an employee, a vacuum of responsibility may be created in the beginning, when the employee has not yet been enabled to take over this responsibility. This vacuum may be filled by asking questions, by co-creating the employee’s learning needs and by adapting them on a regular basis. Although HR managers are to remain learning experts, there may be many questions that can only be answered together with an individual employee or with a team/community of practice. Asking questions, you do not have the answers to, will have to be learned as a new skill.

Developing this mindset of agile learning is something most people are not familiar with. Even self-directed learning has not been a key element of educational or corporate learning in Germany so far. There will be several more questions to have a look at together. How does the company’s learning culture look like? What about the relationship between working and learning for a certain job? Does the job follow the traditional model, where learning is sometimes added as an incentive? Does the job already include some short additional learning periods like e-learning possibilities, which are even organized in a self-directed way? Does the structure of the job no longer separate working from learning? Is learning included on a constant basis in forms of iterative processes and planned periods of reflection (similar to SCRUM)?

Integrated learning ecosystems

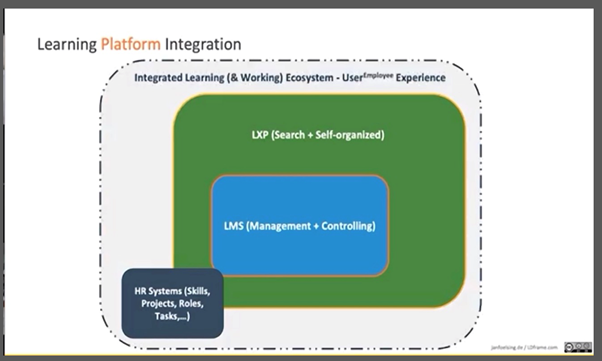

Foelsing (2020) explains the development from traditional learning spaces to “complex (new) learning spaces” in an integrated learning ecosystem. The former consists of events like conferences, workshops, or learning management systems (LMS). Due to the fast and constant information overload, content can be out-dated really fast. As a consequence, the importance of “complex (new) learning spaces” has been growing tremendously. Most of them are integrated into daily working processes, but also have to include projects for explorative learning and have to support the intensification of internal and external networks. These communities of practice are key elements of an integrated learning ecosystem. Moreover, valuable content could be added by external learning platforms (e.g., Cousera or LinkedIn) or by individual content producers (e.g., BE practitioners). While traditional learning spaces are externally controlled and often deliver one-size-fits-all content based on the top-down approach, complex new learning spaces provide learning experiences focusing on the learner’s perspective. Individualized and need-oriented content follows the bottom-up approach and offers opportunities for self-directed experimenting, co-creation, and collaboration beyond the company.

Figure 1. Integrated Learning (& Working) Ecosystem

Integrated corporate learning ecosystems in German companies

Korkut (2020) describes the future learning & development strategy of Mercedes Benz Consulting as “smart learning”. The learning culture consists of work-integrated learning with a small share of face-to-face learning and a clear focus on informal learning, where learning and working can no longer be separated from each other. This model will be supported by learning analytics based on artificial intelligence in order to provide each employee with the best possible learning experience in a modern and informal learning culture. When looking at Siemens, Liebert (2020) also mentions a need for an accelerated time to competency, which is to be achieved by a “corporate learning ecosystem”. He currently considers it as the most promising organizational model, which itself belongs to a ‘multiverse’ of ecosystems. Similar to a biological community of interacting organisms, all the parties involved in the ecosystems are important for the success of its functionality. Liebert (2020) compares it to an orchestra on stage. It does not matter whether they are visible or invisible for the public. BE practitioners could easily be involved as external contributors to this corporate learning system. Nonetheless, employees need time to get used to this job-oriented collaboration. While some early adopters may benefit from explorative learning, many employees still prefer to be at least partly guided on their user-centred learning journeys, where corporate contents and competences will have to be redefined too.

Agile learning – redefining contents and competences

As already mentioned before, the paradigm shift to agile learning in corporate contexts will as well have an impact on the contents and competences necessary for living and working in a VUCA world (Graf et al., 2019). Employees will no longer only remain consumers of contents but turn into (collaborative) producers too. Moreover, for many jobs, knowledge is not sufficient to carry out job responsibilities. Thus, the transfer of knowledge has shifted to action competence acquired in daily learning process. It may take some time to move away from a certificate as only valid proof, especially in German companies. Graf et al. (2019) stress the importance of three key areas: Adapting to a new working environment (digital competence, working in often intercultural virtual teams, and interaction with machines or artificial intelligence), agile working methods (SCRUM, Kanban, etc. requiring self-monitoring and self-awareness) and meta-competences for the transformation process.

The CEFR-informed Business English practitioner as agile learning companion

After having a closer look at the corporate learning context from an HR manager’s perspective, it has become obvious that digital transformation has disrupted traditional learning spaces to a large extent. Nonetheless, most BE practitioners are well-equipped to support employees, HR managers or any other stakeholders on their journey towards agile learning processes within the framework of an integrated corporate learning system. The paradigm shift from traditional to complex new learning spaces can be compared to a continuum. The extent and possibility of BE practitioners’ impact on an agile learning journey both at an individual or organization level will highly depend on their individual skills, competences, mindset, and above all their own agile learning journey. When they have already been able to think about and implement the recommendations of the CEFR Companion Volume (2020), which was published as a complement to the still valid Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR 2001), they will have been able to make the CEFR their friend and to further develop into CEFR-informed practitioners (Nagai et al. 2020).

Many people only associate the famous six-level can-do statements with the CEFR (2001), but it has much more to offer. Apart from the development of communicative language competences, it highlights general competences, which consist of four areas with a clear focus on intercultural topics: declarative knowledge (intercultural awareness), skills and know-how (cultural sensitivity overcoming stereotyped relationships), existential competence (development of intercultural personality) and, what has often been neglected, the ability to learn. The 4D educational model of the OECD 2018 demonstrates the importance of the 21st century learners developing their character, skills, and knowledge within the framework of the 4Cs (collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and creativity), meta-learning, meta-cognition, and a growth mindset. This model is also at the centre of the CEFR CV (2020).

The CEFR CV (2020) puts emphasis on the learner/user as social agents negotiating and co-constructing meaning in a specific context. Furthermore, it completely moved away from a deficit-oriented comparison with a so-called native speaker to inclusive ELF-oriented practices mobilizing general, plurilingual and pluricultural competences by means of interaction and the now even richer model of mediation. Mediation is based on Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory. It creates bridges, has a positive impact on relationships and creates a trusted and safe space for people to communicate. Moreover, completely new descriptors for online interaction were added as well to adapt to the digital transformation.

Lichterfeld (2019) clarifies how the first publication of the CEFR Companion Volume (2020) integrated among others the latest research results from linguistics, English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) and Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) in order to adapt to the challenges of the VUCA world. According to Barbara Seidlhofer (2011), ELF is any use of English choosing it as means of communication among speakers of different L1(s). ELF is constantly adapted by means of accommodation and intelligibility. Kankaanranta/Louhiala-Salminen (2018), researchers from a Finnish School of Business, stress the close relation between ELF and BELF. Professionals involved in international business focus on getting the job done and creating rapport. Additionally, they emphasis the key role of “communities of practice” (Wenger 1998) with competent and confident BELF-users with a flexible mindset. Lichterfeld (2020) shows that BELF researchers stress the importance of ‘collaborative learning’ and ‘situated learning’ with English as a language of identification aiming at an increase in both the ‘collective intelligence’ and in intercultural competence. While Ed Schein (2009), a pioneer in organizational psychology, supports the idea of creating “cultural islands” for successful communication, Camerer/Madder (2012) suggest setting up a ‘conversational contract’, which consists of thinking or talking about communication at a meta-level. The most important aspect will be “how to adapt your behaviour across cultures without losing yourself in the process” (Molinsky 2013).

Summary

Keeping a sufficient level of future employability will highly depend on the employee’s ability to move forward on their agile learning journey. CEFR-informed BE practitioners with a flexible BELF mindset will be able to offer the necessary skills and agile competences to support all the stakeholders involved in the corporate learning process with inclusive BELF practices. These are essential for diversity, equity, and inclusion in our working world, so that employees will be confident and proud users of their global English voice when communicating across cultures in probably mostly virtual teams in the future.

References

Bennett, N. and Lemoine, J. (2014). What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Business Horizons 57(3). Accessed: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260313997_What_a_difference_a_word_makes_Understanding_threats_to_performance_in_a_VUCA_world

Bowie, C. (2020). Understanding the HR manager’s perspective. Accessed: https://besig.iatefl.org/understanding_the_hr_managers_perspective_with_chris_bowie/

Cambridge English Language Assessment and QS Global Employer Survey. (2016) English at work: global analysis of language skills in the workplace. Accessed: http://englishatwork.cambridgeenglish.org/#page_q_skills

Camerer, R. and Mader, J. (2012). Intercultural Competence in Business English. Cornelsen.

Council of Europe, Council for Cultural Co-operation. Education Committee. Modern Languages Division. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Companion volume with new descriptors.

https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4

Foelsing, J. (2020) Integrated Learning Ecosystems. eLearning TV (2020) Summit webinar. Accessed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDsLzJ50Liw

Gartner (2020). Lack of skill threatens digital transformation. Gartner Inc. Accessed: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/lack-of-skills-threatens-digital-transformation/

Giddings, S. (2015). Self-Directed Learning in Higher Education: A Necessity for 21st Century Teaching and Learning. Accessed: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277009137_Self-Directed_Learning_SDL_in_Higher_Education_A_Necessity_for_21st_Century_Teaching_and_Learning?channel=doi&linkId=555dda3b08ae8c0cab2ba168&showFulltext=true

Graddol, D. (2006). English Next. Why global English may mean the end of ‘English as a Foreign Language’. British Council.

Graf, N. (2019) Intro Agiles Lernen für CL Sprint am 15.3.2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjQoKL3c6xU&feature=emb_logo

Graf, N. (2020) Agiles Lernen. Summit Podcast Vol. 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJCz9J7of4E [with English subtitles]

Graf, N., Gramß, D. and Edelkraut, Fr. (2019). Agiles Lernen: Neue Rollen, Kompetenzen und Methoden im Unternehmenskontext. 2. Auflage. Haufe-Lexware GmbH & Co. KG.

Kankaanranta, A. and Louhiala-Salminen, L. (2018). ELF in the domain of business—BELF:

what does the B stand for?. In Jenkins, J., W. Baker and M. Dewey (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca. Routledge, pp. 309–320.

Korkut, S. (2020) Integrated Learning Ecosystems. eLearning TV (2020) Summit webinar. Accessed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDsLzJ50Liw

Lichterfeld, K. (2019). (Business) English as a lingua franca and the CEFR Companion Volume – Implications for the classroom. HLT Magazine 21(2). Accessed: https://www.hltmag.co.uk/apr19/business-english-as-a-lingua-franca

Lichterfeld, K. (2020). Dealing with accent, identity and culture when using ELF. SIETAR Europa Webinar. Accessed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-yGImpaGlI

Liebert, K. (2020) Integrated Learning Ecosystems. eLearning TV (2020) Summit webinar. Accessed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDsLzJ50Liw

Molinsky, A. (2013). Global dexterity: How to adapt your behaviour across cultures without losing yourself in the process”. Harvard Business Review Press.

Nagai, N. et al (2020). CEFR-informed Learning, Teaching and Assessment. Springer Education.

OECD/Asia Society (2018). Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World. Accessed: https://asiasociety.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/teaching-for-global-competence-in-a-rapidly-changing-world-edu.pdf

Schein, E. H. (2009). The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. 2nd edition. Jossey-Bass.

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as a Lingua Franca. OUP.

Techademy (2021). Microlearning: The Future of Professional Training and Talent Development. Accessed: https://techademy.net/blogs/microlearning-the-future-of-professional-training-and-talent-development/

World Economic Forum (2020). These are the top 10 job skills of tomorrow – and how long it takes to learn them. World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. Accessed: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/top-10-work-skills-of-tomorrow-how-long-it-takes-to-learn-them/

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Reflecting on Fossilisation

Laura Edwards, GermanyTo Meta or Not to Meta

Vincent Wongaiham-Petersen, Germany/PhilippinesOtto's English

Thomas Martini, GermanyBoosting Employees’ Intercultural Job Performance with a Flexible Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) Mindset as Agile Learning Companions

Katrin Lichterfeld, GermanyClassroom Language and Teacher Language Proficiency – Ideas for Course Design

Khanh-Duc Kuttig, Germany