Academic Writing

Mahmoud Sultan is a lecturer at the CUCA College in Ajman. He has an MA in TESOL from the British university in Dubai and Birmingham University and is active in many international organizations such as TESOL Arabia, KTEFL and IAFOR. Email: Mahmoudsultannafa@gmail.com

Abstract

The concept of academic writing is one of the most debated topics in academia. This paper explores in-depth academic writing by defining it from different perspectives and exploring its main characteristics that discriminate between creative and informal. Furthermore, it discusses the broad guidelines for providing academic written tasks that develop learners' writing strategies. Moreover, this article guides learners to produce multi-tiered sentences that act as a springboard for creating independent writers capable of producing fully developed writing pieces. Moreover, it explicates the concepts of coherence and cohesion through the techniques for rendering written texts highly concise and expressive through the smooth flow of ideas among sentences and paragraphs.

Introduction

Academic writing is the core pillar of human heritage since it records global records following strict formal grammar, diction and lexeme rules. Thus, it is accredited by colleges, universities, businesses and other academic circles. Academic writing can be identified as the format that conforms to using strict rules, objectivity, and formal language in terms of vocabulary, structures, and resources. Poudel (2018,p.3) adds more depth to the concept of academic writing by identifying it as “Academic writing, in a broad sense, is any writing assignment accomplished in an academic setting such as writing books, research paper, conference paper, academic journal, and dissertation and thesis.” From another perspective, Irvin (2010,p.8) describes academic writing as "Academic writing is always a form of evaluation that asks you to demonstrate knowledge and show proficiency with certain disciplinary skills in thinking, interpreting, and presenting.”

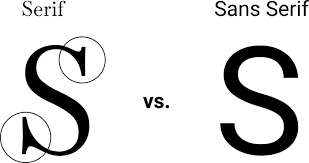

Oshima and Hogue (2007) probe the concept and the purpose of academic writing by purporting that it is the writing used at academic establishments such as universities, colleges and schools. Furthermore, they contend that it is distinguished from creative and personal writing in terms of requiring writing multi-tiered complete sentences, avoiding slang or colloquial expressions and contractions. Thus, they agree with Poudel and Irvin on the academic establishment's priority and function of academic writing. Academic writing also necessitates the total level of formality regarding using complete verbs instead of phrasal or prepositional verbs. Additionally, formality requires the following struct a strict format concerning the paper size, font type and size.

The characteristics of academic writing

Academic writing is distinguished by having explicit, definite attributes that differentiate it from other types of writing and makes it accredited in the academic circle.

Strict format

Academic writing follows strict formatting with paper choice, ink colour, font type and size, headings, and spacing. The paper should be white, 8.5 by 11.5 inches, while the ink must be black or dark blue. Additionally, font type and size are of pivotal vitality for academic writing. Therefore, writers should use sans-serif styles (without decorations at the end of the letter), notably Times New Romans, Arial, Helvetica and Calibri, because they are clear and do not obscure the written assignment when emailed. By contrast, other resources recommend Cambria and Veranda.

https://www.google.com/search?q=what+does+it+mean+sans+serif+font&sxsrf

According to Capstone Editing(2017), Time New Romans and Arial are the most accredited fonts at all universities as they are clear and add a touch of formality to the written tasks. Capstone does not recommend using fancy fonts since they render texts informal and may obscure the meaning when sent electronically. It also suggests using size 14, bold and centred for titles, size 12, bold left-aligned for headings. Regarding texts, Capstone confirms using size 12 with 1.5 spacing among lines; thus, it agrees with the APA and MLA referencing styles.

Coherence and cohesion

Coherence and cohesion are pillars of academic writing since their negligence complicates the meaning and cripples the smooth flow of ideas among sentences and paragraphs. Coherence can be identified as the logical order of information in sentences and paragraphs that demonstrates reasonable relations among ideas to convey the targeted messages directly and concisely. Wali and Madani (2020, p. 49) argue that coherence and cohesion are the keys to academic writing as they purport, "Coherence, cohesion and unity are considered the characteristic features of good writing. Thus, one should follow the mentioned characteristic to help the readers follow the logical sequence of the written text.”

Coherence and cohesion are mutually linked because they have a strong interdependence bond since coherence cannot be achieved without a high standard of cohesion. Cohesion implies the proper ways of connecting sentences or the glue that links sentences in such a way that allows a smooth flow of ideas throughout the whole text resulting in coherence. Taboada (2004) defines cohesion as the internal hanging links within the text that connect parts of the text. From another perspective, Yule (2008) identifies coherence as the ties or relations connecting all text parts. Thus, both Taboada and Yule agree on the crucial function of cohesion as a multi-levelled linking device that creates an expressive textual texture presenting a purposeful meaning.

Halliday and Hasan (1976) add more depth to cohesion perception as they divide it into two forms. Firstly, grammatical cohesion can be achieved through using specific structural devices such as coordinators, subordinators, ellipsis, references or carrying out clause reductions. The following sentences present the impact of grammatical cohesion, demonstrated through the conciseness and the strength of the texture and the meaning. These examples clarify grammatical coherence.

- The professor is highly appreciated. He understands our problems.

- The professor who understands our problems is highly appreciated.

- The librarian chose 20 books. These books consist of many chapters covering a plethora of themes.

- The librarian chose 20 books. They consist of many chapters covering a plethora of themes.

Lexical cohesion is complementary to grammatical cohesion as it renders texts more cohesive and coherent based on the meticulous utilization of vocabulary through synonyms, antonyms, collocation or reiteration. The following examples display how lexical devices can be used to make sentences cohesive.

- I saw a man running in the street. The man was wearing a T-short. (reiteration)

- Can I visit your friends tomorrow? You can call on them next week. (synonym)

- Where can I find a cheap car as I am short of money? Unfortunately, all cars are expensive these days. (antonym)

Referenced evidence

Academic writing requires solid evidence based on information collected from highly reputed resources to support all the arguments stated in the written tasks, increasing their credibility and enriching their impact.

Organized structure

Written tasks should be academically structured as they should have clear-cut parts based on the nature of the topic. However, most academic research papers should have an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion.

Balanced discussion

Academic papers are balanced as they probe all facets of the argument from different perspectives, objectively noting that writers should be fully knowledgeable about the assigned topic.

Critical view

When writing an academic paper, writers are not supposed to describe or paraphrase the main ideas of a specific topic. They must evaluate, assess, analyze and judge the collected data and their resources before integrating them into their work (Writers. net, 2021).

How can academic written tasks be produced?

Vocabulary Usage

Academic written tasks require following up strict rules of writing that distinguish it from creative or personal writing. Kemp (2007) argues that writers should avoid wordiness by eliminating buzz, fluffy words, and phrasal verbs. They should also write clearly and concisely using specific language, avoiding jargon, colloquial expressions and anthropomorphism. These terms are loaded with many connotations that disguise the meaning and make the texts more informal and subjective. Furthermore, academic writing necessitates evading using noun strings and redundancy since they form a kind of digression that makes the written texts rather lengthy, characterized by circumlocution resulting in more arduous efforts to grasp the theme of the texts.

Sentences variation

Varying sentences is another essential technique for producing exceedingly academic writing. Writers should use various types of sentences to express ideas precisely and unswervingly. For example, they should use simple sentences to highlight essential points, whereas compound sentences are used to add more details of equal importance. Complex sentences should be utilized when showing subordinating relations such as reasons, contrast, and conditions. The compound-complex sentences are mainly applied to show more complicated relations and more development of ideas.

However, sticking to one type of sentence undermines the quality of the written texts. For example, depending on simple sentences leads to choppy texts, results in shallow ideas, and slow reading due to the slow flow of ideas. By contrast, utilizing complex and compound-complex sentences results in a wordy style that perplexes readers and increases comprehension challenges.

Fire Hydrant or Garden Hose Approaches

Bowman (2010) examines the ways of producing academic written texts. He argues that the type and the quantity of information decide the most appropriate style for producing written tasks. Writers are to use the fire hydrant techniques for providing detailed information and discussing a particular topic from various facets minding explanations and considerations. Thus, this approach is appropriate for experts and advanced audiences since it enables them to comprehend the topic thoroughly to enrich their information. By contrast, the garden hose approach is used for conveying limited information to ordinary readers who aim to have an overall idea on the topic; nevertheless, this information is not necessary to be shallow or superfluous. Hence, he sums up this concept as “… provide the information desired by a more general reading audience or the answer to a specific question(275).” Accordingly, writers should use an approach that considers their audience's needs and interests to conform to the academic writing rules.

From another point of view, Bowman (2010) calls for diversifying the internal constituents of sentences to avoid the monotonous, boring washboard effect that results from following the firm English language structure “SVOCA”. This rule implies forming sentences as follows:

Subject++ verb++ object or complement.

When following this style strictly, the tone and the structure will be recurring, like passing the hand on a washboard. The sound will be high and influential at the beginning, fading away. Similarly, using the SVOCA writing style results in gradual fading focus due to the rhythmic structuring of sentences.

Therefore, writers should restructure their sentences to add more vividness and diversity to their written tasks.

1 Fronting

This strategy implies moving one part of the sentence to the initial part to sustain its significance.

- A policeman stopped me while I was driving my cart a little bit fast.

- While I was driving my car fast, a policeman stopped me.

2 Cleft Sentences

A Cleft sentence is another strategy that adds more focus to a specific part; thus, it shifts on a particular part of the sentence and breaks the structure's flatness.

I will use this book in my research since it responds to my audience’s needs.

It is this book that I will use in my research since it responds to my audience’s needs

It is because this book responds to my audience's needs that I will use this book in my research. (Swan,2002)

3 Voice

Active voice should be mainly used in academic writing since it conveys the text's message directly, clearly and economically. Furthermore, it is an attitudinal style because it highlights the performer of the action, so it has a more substantial impact and credibility. On the other hand, passive voice is not recommended in academic writing since it is wordy, resulting in a weak argument as the subject is subordinated or even deleted. However, writers can utilize passive voice when spotlighting the object of the sentence or when the doer is not essential or unknown.

- Someone invented the wheel thousands of years ago.

- The wheel was invented thousand years ago.

The second one is more expressive as the wheel is more important than someone. Additionally, it adds diversity to the sentence structure.

4 Hedging

Since academic writing is objective, using hedging language enriches this trend since it does not instil judgmental language. Hedging means using words such as seem, maybe, can be…, etc., that allows a broader scope of expressing ideas that opens the floor for free views that prevent biased tendency. For instance, the following sentences demonstrate the constructive impact of hedging on the discussion continuity.

- Smoking leads to many detrimental heart diseases.

- Smoking can lead to many detrimental heart diseases.

The first sentence is subjective as the writer states his opinion bluntly, so there is no chance for discussion. However, the second sentence conforms to the rules of academic writing as it is objective and non-judgmental; thus, the counterargument is welcomed. (Bovee and Thill, 2013)

5 Newness and weight

Nafa (2022, p.173) explores the impact of the newness and the weight impact on academic writing as he contends that “Owing to the criticality of academic writing, more precise rules should be considered when producing texts.” Firstly, familiar ideas or structures should be placed at the beginning of the sentence to introduce the new ones; consequently, it facilitates comprehension and adds a sense of engagement or suspense to the new idea. Furthermore, new ideas should be introduced in a familiar language, while familiar topics should be presented in more challenging language to simultaneously make the written text more comprehensible and demanding.

From another perspective, the weight approach also counts on the creditability of academic writing. Following the layout of English language sentences, important information should be placed at the end of the sentence as the beginning and the middle parts are used as essential elements. The first part of the sentence hosts the second important information through fronting, while the middle part has the lowest and the least important information. When examining the following sentences,

- The manager will take tough decisions at the end of the weekend.

- At the end of the weekend, the manager will make a serious decision.

It is noticed that “weekend” is the essential part in the first sentence since it is in the end, and then it becomes the second most important in the second sentence as it is in the initial position.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, academic writing is not only crucial for producing free-error pieces of writing, but it is highly vital for assessing students' syntactic and lexical abilities. Teachers can assess these potentials by utilizing academic writing as performance tests that evaluate students' knowledge of structures, vocabulary and writing mechanics mastery. This will enable teachers to locate the points of strengths and builds on them and the points of weaknesses and addresses them.

References

Bovee, C. and Thill, J., 2013. Excellence in Business Communication. 10th ed. Boston: Pearson, pp.178-181.

Bowman, D., 2010. 300 Hundred Days of Better Writing. New Mexico: Precise Edit.

Capstone Editing, 2017. How Should I Format My University Essay?[Blog] Capstone Editing, Available at: <https://www.capstoneediting.com.au/blog/how-should-i-format-my-university-essay> [Accessed 19 May 2022].

Irvin, L.L., 2010. What Is “Academic” Writing? Writing spaces: Readings on writing, 1, pp.3-17.

Kemp, A., 2007. Characteristics of Academic Writing in Education. Master. South Dakota State University.

Oshima, A. and Hogue, A., 2007. Introduction to academic writing (p. 3). Pearson/Longman.

Poudel, A.P., 2018. Academic writing: Coherence and cohesion in paragraph. Retrieved August, 8, p.2019.

Swan, M., 2002. Practical English Usage: International Student. 8th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.14-17.

Taboada, M. T. (2004). Building coherence and cohesion: Task-oriented dialogue in English and Spanish. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Wali, O. and Madani, A.(2020) "The Importance of Paragraph Writing: An Introduction." organization 3.07.

Writers.net, 2021. The Special Characteristics of Academic Writing. [Blog] Writing Blog, Available at: <https://4writers.net/blog/the-special-characteristics-of-academic-writing/> [Accessed 20 May 2022].

Yule, G. (2008). The study of language. (3rd ed). New Delhi: CUP.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

Academic Writing

Mahmoud Sultan Nafa, United Arab EmiratesAbstract Writing: Challenges and Suggestions For Non-English Researchers

Irina Tverdokhlebova, Russia;Liliya Makovskaya, Uzbekistan