- Home

- Lesson Ideas

- Stimulating Students’ Creative Thinking During a Primary Research Task in the Academic English Module

Stimulating Students’ Creative Thinking During a Primary Research Task in the Academic English Module

Aisulu Kinjemuratova is an Academic English lecturer at Westminster International University in Tashkent. Her research interests are critical thinking development, methods of teaching and learning foreign languages, language and culture, power of feedback. E-mail: akinjemuratova@wiut.uz

Dildora Tashpulatova has been teaching Academic English to foundation students at Westminster International University in Tashkent (WIUT). She holds MED in Educational Psychology from Texas A & M University. Her research interests include critical thinking development, student motivation and academic performance, learned helplessness and learning goals. E-mail: dtoshpulatova3@wiut.uz

Introduction

From the previous years, we have observed that the research report assessment task that we teach to first-year students at Westminster International University in Tashkent poses obstacles due to its complexity and novelty. The students often struggle to choose a topic for their research, narrow it down to define the focus, do secondary as well primary research selecting appropriate research tools, and, as an outcome, analyze and interpret collected data to reflect upon the findings in a report. To facilitate students’ work and enable them to have a positive experience, we design activities that encourage students to think critically and reflectively. We also have been convinced that the use of creativity-building activities is also an efficient strategy to make sure students reach their goals and are satisfied with their performance.

Forming and developing students’ creative thinking skills have become one of the most significant attributes of the 21st century education in many fields. The importance of creativity has been remarkably emphasized in many research articles and projects by scholars and professionals from various fields (Akpur, 2020; Puccio & Lohiser, 2020; Facione, 2018; Benade, 2017; Seechaliao, 2017; Donnelly & Barrett, 2008; Marks & Huzzard, 2008; Gurteen, 1998).

Definition

So, what is creativity?

Normally, creativity is accepted as the generation of ideas when innovations turn ideas into action (Gurteen, 1998; Marks & Huzzard, 2008). It is associated with inventing something new. Facione (2018) defines creative thinking as the form of thinking that leads to new views, innovative approaches, and perspectives, novel ways of perceiving and considering concepts. He believes creative thinking encompasses brainstorming, analytical thinking skills, metaphorical thinking, communication, creative problem solving, and originality. Another definition of creative thinking is the ability to solve a problem and the development of a structured way of thinking logically related to the content of knowledge (Prusak, 2015). In general, creative thinking is a mental activity in the form of thinking that can produce concepts, ideas, knowledge, understanding, and discoveries.

Academic English, research, and creativity

Psychologists, educators, and trainers unanimously agree on the importance of integrating creative thinking into teaching Academic English, stating that it can engage in cognitive activities which require the application of problem-solving skills, decision-making as well as content knowledge and group work skills (Gladushyna, 2019; Sieglova, 2017; Gaspar & Mabic, 2015; Hughes, 2014).

Furthermore, research skills help students to critically investigate problems, and if appropriate, produce and evaluate relevant data and test ideas that characterize the information age. To develop abilities such as communicating, collaborating, critical thinking, and creativity, an effort is made with research-based learning. Students must be triggered to think outside of their existing habits by involving new ways of thinking. These skills can be improved and optimized by doing research (Kembara, Rozak & Hadian, 2019).

The role of a teacher

Creative thinking can be incorporated into learning by teachers, so teachers should be able to carry out the mandate of developing students’ creative thinking skills. This is in accordance with the opinions of Wheeler, Bromfield, and Waite (2002), who stated that the teacher's task is to provide the best conditions for students to acquire relevant thinking skills.

The instructor’s level of motivation is an important factor that relates to students’ creative thinking (Horng et al., 2005; Davis et al., 2014; Palaniappan, 2014, cited in Wongpinunwatana, Jantadej & Jantachoto, 2018, p.48). If the ability to be creative is indeed vital for students’ future success, teachers must explicitly foster and teach creativity in school (Robinson, 2001, cited in Gregory et al., 2013, p.3). Teachers should include learning that is hands-on and experience-based to motivate students, supply sufficient information and experiences so mental models can be formed and used flexibly, and provide variable practice.

Approaches

To understand and be able to organize instruction that reinforces creative thinking in students, it is reasonable to look at different approaches that could serve the purpose. There are several approaches that could be utilized, and we have selected several that are most relevant and effective. They are collaborative, decision-making, problem-based, content-based, motivational, and reflective approaches.

Collaborative approach

Collaborative learning is a joint effort by all participants within a group of students, where they work together to search for understanding, meaning, or solutions to accomplish a task (Hong, 2011, cited in Wongpinunwatana, Jantadej & Jantachoto, 2018, p.48). Collaborative learning requires individuals to take responsibility for a specific section and then coordinate their respective parts together (Kyndt et al., 2013, cited in Wongpinunwatana, Jantadej & Jantachoto, 2018, p.48). Knowledge can be created within members in a group where members actively interact sharing experiences and taking on asymmetric roles (Mitnik et al., 2009, cited in Wongpinunwatana, Jantadej & Jantachoto, 2018, p.48).

Decision-making approach

Creativity, according to the investment theory, is in large part a decision. The view of creativity as a decision suggests that creativity can be developed. Simply requesting that students be more creative can render them more creative if they believe that the decision to be creative will be rewarded rather than punished (O’Hara & Sternberg, 2001, cited in Sternberg, 2006, p.90). Being creative involves first making the decision to produce new ideas, examining them, and then proposing them to others (Sternberg, 2006).

Problem-based approach

The problem-based approach enables students to engage in real-life issues to tackle and come up with achievable solutions. Benade (2017) states that in problem-based classes, “students work collaboratively, solving real-world problems, along with content knowledge and a range of skills, which help to motivate students” (p.36). Applying this approach, teachers provide a range of problems as “the initial stimulus and framework for learning” (the Center for Teaching and Learning, 2001, p.1). Students’ problem solving, self-directed, collaborative learning skills, and motivation levels are aimed to be developed during the problem-solving process (Hmelo-Silver, 2004 cited in Birgili, 2015, p.75).

Content-based approach

A student’s ability to creatively apply the information they have learned—creativity derived from content knowledge—is best supported when creative thinking is taught in tandem with subject matter content, rather than in a standalone way, divorced from content. Many researchers have argued that every individual possesses the ability to think creatively, at least within contexts (Amabile, 1996; Kaufman & Beghetto, 2009 cited in Gregory et al., 2013, p.3). It has been stated that domain-specific content knowledge is the basis for creative thinking (Weisberg, 2006, cited in Gregory et al., 2013, p.6).

Motivational approach

Further, research has shown that creative thinking is influenced by various circumstances, including whether work is collaborative and the extent to which individuals are motivated to solve a problem (Brophy, 2006, cited in Gregory et al., 2013, p.3). Intrinsic, task-focused motivation is also essential to creativity. The research of Amabile (1983) and others has shown people rarely undertake truly creative work in an area unless they are truly interested in what they are doing and focus on the task rather than the prospective rewards, according to the necessity of such motivation for creative work (cited in Sternberg, 2006, p.89).

Reflective approach

Students’ responsibility is to engage in detailed examination of novel subject resources and immerse into profound thinking. As Halpern (2007) contended, there is a worldwide demand for educational systems that empower students with the skills and abilities required for deep and reflective learning. Reflection is employed when students reassess the previous action and perform the next one.

Students’ reflection needs to underpin all stages of assessment through providing opportunities for their decision-making, initiation, and creativity. A potential benefit to make the link between learners’ engagement and success can be obtained through promoting a reflective approach to learning where they take responsibility for what and how they learn (Djoub, 2017).

Activities

Mind-mapping

According to Al-Jarf (2009), the mind map is an effective tool for increasing students' ability to develop, visualize, and formulate ideas (cited in Zubaidah, 2017, p.80). A mind map is also a tool that converts tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. It can be used in conjunction with a range of approaches for productive learning to encourage students to investigate the relationships between material and to stimulate creative thinking (Davis et al., 2000, cited in Zubaidah, 2017, p.80).

In the AE module, the mind map is used at the early stage of students’ research. The students, for example, develop mind maps both individually and in groups when selecting a general topic from the suggested options and narrow down the focus by brainstorming ideas. Their task could be facilitated if the students are given questions, and at the same time, formulate their own questions to determine the focus. For example, questions such as who? where? when? how? could be used first, and then students could apply their questions such as which aspect? what characteristics? To illustrate, we chose the topic of Presents/Gifts and created a mind map on it.

|

Hand-made gifts |

Traditional gifts/presents |

Gifts/presents for teenagers |

|

Value of gifts/presents |

Presents/Gifts |

Selecting gifts |

|

Necessity of gifts/presents |

Superstitions and gifts/presents |

Future of gifts/presents |

Questions that students could use:

How important are gifts for the young generation today?

What are the most popular gifts among the older generation?

Why do people living in Tashkent give gifts?

What gifts do students of WIUT prefer to receive?

Free research

Another activity students could do using the inquiry learning model is by encouraging students to exercise autonomy. The students could be tasked to think of a topic themselves and create a list of issues or develop a project by using their imagination. They could, for example, set a goal of finding out the most likable library facilities. Then, they could first think of the list of aspects to consider such as the colors, space, shelves design, books’ categories allocation, furniture. They could make up questions for each of the aspects listed and when they come to class, they could ask their peers to answer the questions they prepared. Having collected the answers, they could analyze the collected information at home, or if possible, in class and figure out the most preferred library design. The peers could also be asked to evaluate the questions they responded to by focusing on criteria such as clarity, logic, relevance, importance, and actuality. This activity could be used rotationally. This activity involves collaboration and boosts student motivation as the students will have freedom of choice and learn about areas for improvement.

Peer-teaching

Creative learning takes place in student-centered environments and through active learning experiences including role-plays. Students can benefit from trying themselves in the role of teachers as they see the task from a different angle, thus, are more motivated to complete the task at hand. In the role of a teacher, they could implement an activity they designed in their small groups. For example, the teacher could assign students to teach their peers to design survey and interview questions. They could also share other smaller roles such as teacher assistant, handouts developer, note-taker, and facilitator. The creative part of this type of activity is that students try on new roles and learn to make autonomous decisions. They decide on what to teach, how to teach it, and have control over the atmosphere in the classroom during the process. This, in turn, might have a motivational effect on their own learning and they could start seeing their task as more interesting and manageable.

Sharing academic experiences through guest seminars

To spark students’ interest even further, the teacher could use multiple resources to vary the classroom activities. One such activity could be done with the help of students from senior levels who had experience in conducting research in the previous years. The teacher could invite some students to the class and negotiate their mission beforehand. Materials and ideas could be provided to the invited students who could also suggest how to teach students to prepare the task. For example, the teacher could ask the students to participate in an interview by less experienced students who could ask their questions about their experiences. The teacher could instruct students to ask questions in small groups and make a list of questions that they cannot ask (as they are too obvious or simple) to encourage creative thinking. This is a productive experience exchange and can help students build some confidence as learners.

Case studies

From our observation we have seen many issues students face during completion of the task. Thus, to prevent similar scenarios from happening students could study different cases of issues in completing the task such as writing literature review, designing surveys and interviews, analysis, and interpretation of data. Thus, students can benefit from studying scenarios and finding creative solutions to the issues described.

For example

Case study 1

A small group of student researchers have selected a topic for their research and have decided on the focus of their study. They now need to search, find, and review research-based articles on a similar topic. However, the students are not sure how to organize their work. They cannot decide on the sequence of steps to cope with the challenge. What steps could they follow to maximize the efficiency of their work?

Case study 2

A small research group have collected quantitative data from a recent survey they conducted on The Most Common Issues Students Face When Entering a University. They have explored aspects such as internal and external issues, gender differences, student performance at entrance, facilities and services, rules and regulations, and academic life. How can the findings be presented in an interesting and clear way?

When doing such tasks, students could be asked to vote for the best solutions by their peers to stimulate their interest and increase their motivation in doing their work for the CW.

Discussion forums

An additional tool to facilitate students’ work can be use of discussion forums where they can share their thoughts, exchange questions, provide both peer and instructor feedback. One advantage of this online activity is that the teacher can detect any issues students might be having and suggest ways to overcome them. This can be beneficial for small groups as it can enable them to make individual contributions and have more time to post well-balanced ideas.

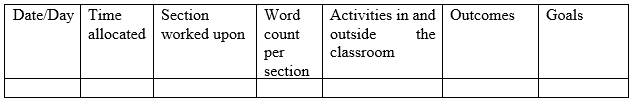

Log files

Log files could be used by students to monitor, control, and track their progress in completing parts of their research work. This tool could be utilized throughout the semester and presented during feedback sessions. It boosts students’ creativity, and at the same time, helps them to see what they have achieved and what areas they need to give more attention to.

Reflective journal

After each session, we can ask students to prepare a written journal to deliberate on what they have learned from the lesson, how they learned the material, and what their weaknesses and strengths were. Students can reflect on what they have learned from their teacher, research report writing experience, and class discussions.

Conclusion

In sum, activities targeting stimulation of creative thinking in students in the Academic English module can help build dynamic and student-centered learning environment and boost their autonomy. It is recommended to employ the activities in teaching practices to encourage students to be more creative in their learning, and thus, enable them to enjoy the academic process as well as cope with the assigned tasks.

References

Akpur, U. (2020). Critical, Reflective, Creative Thinking and Their Reflections on Academic Achievement. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100683

Benade, L. (2017). Being a Teacher in the 21st Century: a Critical New Zealand Research Study. Auckland:Springer.

Birgili, B. (2015). Creative and Critical Thinking Skills in Problem-based Learning Environments. Journal of Gifted Education and Creativity, 2(2), 71-80.

Center for Teaching and Learning (2001). Problem-Based Learning. Speaking of Teaching. 11 (1) https://arrs.org/uploadedFiles/ARRS/Life_Long_Learning_Center/Educators_ToolKit/STN_problem_based_learning.pdf

Djoub, Z. (2017). Supporting Student-Driven Learning: Enhancing Their Reflection, Collaboration, and Creativity. In: Alias, N. & Luaran, J. (Eds) Student-Driven Learning Strategies for the 21st Century Classroom. Pp. 331-351. Hershey: IGI Global.

Donnelly, R., & Barrett, T. (2008). Encouraging Student Creativity in Higher Education. In B. Higgs & M. McCarthy. (Eds.) Emerging Issues II: The Changing Roles and Identities of Teachers and Learners in Higher Education. Cork: NAIRTL.

Facione, P. (2018). Creative Thinking Skills for Education and Life (teaching creativity). https://www.asa3.org/ASA/education/think/creative.htm

Gaspar, D. & Mabik, M. (2015). Creativity in Higher Education. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3(9), 598-605, doi: 10.13189/ujer.2015.030903.

Gladushyna, R. (2019). Challenging Critical and Creative Thinking in Foreign Language Teaching and Learning. Slavonic Pedagogical Studies Journal, 8 (1). http://www.pegasjournal.eu/files/Pegas1_2019_7.pdf

Gregory, E., Hardiman, M., Yarmolinskaya, J., Rinne, L. and Limb, C. (2013). Building Creative Thinking in the Classroom: from Research to Practice. International Journal of Educational Research, 62, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.06.003

Gurteen, D. (1998). Knowledge, Creativity, and Innovation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2 (1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673279810800744.

Halpern, D. F. (2007). Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking. 3rd. edition, Psychology Press.

Hughes, J. (2014). Critical Thinking in the Language Classroom. https://cdn.ettoi.pl/pdf/resources/Critical_ThinkingENG.pdf.

Kembara, M. D., Abdul Rozak, R. W. and Hadian, V. A. (2020). Research-based lectures to improve students' 4C (communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity) skills. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 306, 21-26. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Lohiser, A. & Puccio, G. (2020). Dare to be Disruptive! The Social Stigma toward Creativity in Higher Education and a Proposed Antidote. In: Jain P. (2021). (Ed.) Creativity - A Force to Innovation. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93663

Marks, A. & Huzzard, T. (2008). Creativity and Workplace Attractiveness in Professional Employment. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting. 12. 225-239. 10.1108/14013380810919868.

Prusak, A. (2015). Nurturing Students’ Creativity through Telling Mathematical Stories. In: Singer, F. M., Toader, F. & Voica, C. (Eds.) The 9th Mathematical Creativity and Giftedness International Conference Proceedings. Romania https://www.mcg-9.net/pdfuri/MCG-9-Conference-proceedings.pdf#page=18.

Seechaliao, T. (2017). Instructional strategies to support creativity and innovation in education. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(4), 201-208. http://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n4p201

Sieglova, D. (2017). Critical Thinking for Language Learning and

Teaching: Methods for the 21st Century. In Cross-Cultural Business

Conference 2017, 189.

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The Nature of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 18(1), 87–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1801_10

Wheeler, S., Bromfield, C. & Waite, S. (2002). Promoting Creative Thinking Through the Use Of ICT. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18 (3), 367-378. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0266-4909.2002.00247.x

Wongpinunwatana, N., Jantadej, K. and Jantachoto, J. (2018). Creating Creative Thinking in Students: a Business Research Perspective. International Business Research, 11 (4), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v11n4p47

Zubaidah S., Fuad, N. M., Mahanal, S. and Suarsini, E. (2017). Improving Creative Thinking Skills of Students through Differentiated Science Inquiry Integrated with Mind Map. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 14(4), 77-91. doi: 10.12973/tused.10214a

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Stimulating Students’ Creative Thinking During a Primary Research Task in the Academic English Module

Aisulu Kinjemuratova, Uzbekistan;Dildora Tashpulatova, UzbekistanEffective Activity Modification Techniques For EFL/ESL Teachers

Gulbakhor Mamadiyeva, Uzbekistan;Dilrabo Babakulova, Uzbekistan;Malika Kasimova, Uzbekistan