- Home

- 21st Century Skills - Technology

- An Aggregated Automated Anonymized Assignment Collection (A4C) System for Translation Classes

An Aggregated Automated Anonymized Assignment Collection (A4C) System for Translation Classes

Daniel Svoboda is an Assistant Professor in the Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS) in Seoul. Over a teaching career that spans more than a decade, Daniel has worked with learners as diverse as kindergarten students and company executives, and just about every age level in between at private academies, elementary schools, high schools, universities and in-house corporate training programs. A fluent Korean speaker, Daniel has presented papers at more than thirty international conferences both in Korea and abroad on topics related to TESOL, literary theory and translation. Email: dansvo82@outlook.com

Introduction

This paper details the development and use of an ad-hoc Aggregated Automated Anonymized Assignment Collection (A4C) System in Korean-English translation classes at the Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation (GSIT) at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS) in Seoul, Republic of Korea. Prompted by a variety of unmet needs in the assignment submission process, the author considered a variety of different options to aggregate, automate and anonymize the submission of translation assignments and finally settled on the use of a free, flexible, cross-platform system that satisfied most of those same requirements. Following a brief introduction of the classroom environment and the rationale behind the need to collect and collate multiple student assignments anonymously in an automated manner, the paper will examine the existing systems in place and their inadequacies, the process of using the new system, benefits from use of the new system and directions for future research. Attention will also be paid to the advantages of anonymity in the classroom and why anonymizing assignment submission may be useful in select cases.

The problem

The Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul is a professional graduate school founded in 1979 that provides graduate-level courses and degrees to aspiring translators and interpreters in a wide range of different languages. Approximately half of the courses on offer each semester focus on translation, or the conveyance of text from one language to another in written form. Translation courses may take a variety of formats but essentially consist of a theoretical focus on translation theories as well as a practical component in the form of real-world translation. This practical component is made all-the-more realistic and effective with the provision of faculty feedback regarding student translations. A typical translation course will involve the completion and submission of a number of translation assignments, known as translated texts (TT), into the target language, followed by verbal or written feedback from the faculty member on the TT’s faithfulness to the original source text (ST), overall structure, lexis, grammar, punctuation, formatting and a myriad of other issues. This paper will limit itself to an analysis of the logistics involved in the submission of translation assignments from multiple students and one potential solution to such logistical difficulties developed by the author.

The existing system

The Hankuk University of Foreign Studies has in place a fairly standard school portal/learning management system (LMS) known as E-Class. The E-Class platform provides a range of tools that allow for file uploading, messaging, online quizzes and other functionality. A resource room page and open bulletin board page within the platform enable both faculty and students in each course to upload individual files for sharing. Files uploaded are posted individually and include a timestamp and the name of the user posting the file. Uploaded files cannot be viewed or modified online, but instead must be downloaded. This, along with support for only two languages and weak mobile device support, limits the flexibility of the system. Moreover, the interface and functionality of the platform as a whole have not been upgraded in any significant way over the past five years.

The university follows a typical sixteen-week semester, which means the average graduate-level translation class with up to twelve students includes anywhere from 12-14 separate assignments of approximately 200 words in length. Faculty members are free to implement their own assignment collections systems, with most choosing to utilize either submission of printed hard copies or uploading of Microsoft Word DOC-format files via E-Class. Since a key part of translation course methodology is the comparison of different versions of translated texts, faculty members must either manually retype segments from printed assignments or open each uploaded DOC file individually and copy-and-paste the relevant sentence/segment for inclusion within in-class feedback. This process is time-consuming and cumbersome as well as potentially bias-inducing for the reasons outlined the subsequent paragraph.

The root of the potential bias incurred is the lack of anonymity in the submission process. The submission of either printed assignments or upload of electronic files under a student’s user ID immediately identifies the student to the faculty member and potentially to all their peers in the same course. Students in classes at GSIT are typically part of the same admissions cohort and finish their degree with the same cohort over a two-year period. After graduating, they often work with graduates from the same cohort for the remainder of their professional careers. As such, some GSIT students are unnerved by the thought of potentially being embarrassed through the revelation of translation mistakes in front of their current peers and future colleagues.

The aforementioned limitations of the existing E-Class system and the unique needs of both the faculty and students of GSIT make clear the need for an efficient assignment collection system that ensures aggregation, automation and anonymity. Such a system must collect and collate translations from up to a dozen students, allow faculty to export translation segments for comparison or inclusion in class from multiple assignments in a variety of different file formats, make corrections on the fly to student translations and allow for both anonymity and student identification, if needed. The lack of an apparent turnkey solution and finite budget resources encouraged the development of an ad-hoc system that satisfied the stated requirements but didn’t impose an undue technical or monetary burden. The details of the said system are provided in the next section, after a discussion on the benefits of anonymity in the classroom.

The benefits of anonymity

Students at GSIT are generally well aware of the program requirements and associated pressures before they even sit for the admissions exam given annually in October. Once admitted, a majority of each cohort spend up to nine hours a day, five days a week together at school, often enrolling in the same classes and spending additional time in tight-knit small group study sessions. This cohesion enhances academic outcomes and encourages the study body to remain committed to the goal of passing the infamously difficult graduation exam but, as mentioned previously, may place a strain on interpersonal relations both within and outside the confines of the classroom. Additionally, the widespread adoption of the ‘critique’ method within classes, in which both faculty and fellow students enumerate an itemized list of assumed and actual errors in a particular student’s translation or interpretation, only increases the level of pressure students experience. Given that the goal of the two-year MA program is to train professional translators and interpreters of the very highest quality to advance the national interest, this pressure is not insignificant, especially when individual students are placed under the limelight.

Hoping to alleviate such potential tensions, the author sought out a system that would allow students to submit their translations anonymously while, at the same time, not impose a burden in terms of anonymizing each and every student’s submissions. The key principle to be upheld in the process was that submissions should be anonymous, to prevent faculty bias when selecting TT segments for analysis. Subsequently, all comparisons of translated segments brought up for review during classes remained anonymous by default, unless a student decided it was in their interest to come forward and reveal their authorship of the said segment. One key insight from the adoption of the system was that students were more likely to come forward and claim authorship if their translation was praised in front of the class or if a nagging translation issue such as inherent ambiguity was present and required clarification.

The esteemed playwright Oscar Wilde once noted that, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth” (Wilde, 2003). The same often applies to student participation in the language learning or translation environment. Students feel most comfortable analyzing and revising written work, be it their own or that of their peers, when authorship is not readily attributed.

Anonymity also promotes quality in the classroom. In a comprehensive study on the use of anonymous feedback in educational settings, Bergstrom, Harris, and Karahalios assert that “Students learn more when they actively engage in the classroom. Though some students participate, it’s expected that five students out of 40 will come to dominate any classroom discussion” (Bergstrom, et al., 2011). Although a typical GSIT class has only one quarter the number of students mentioned, the same principle applies. In the same study, they also claim, “Students try to present a positive image of themselves to their peers. Thus, they often avoid volunteering information due to evaluation anxiety, a fear of being judged by others for making a mistake or being the focus of attention. It’s all too easy to remain silent” (Bergstrom, et al., 2011). Other research outcomes back up this claim. The authors of Anonymity and Classroom Participation (Ray, et al., 2014) argue that “To increase student participation in the classroom, we need to ensure students feel comfortable. One way to achieve this is through the introduction of anonymous technologies, which allow students to share their opinion without being identified, and hence without the fear of being judged.” Anonymization helps blur the boundaries between the more active and less active student segments by easing evaluation anxiety and encouraging participation from the previously less active group. When students no longer fear judgment, a spirit of openness and participatory discussion can take root in its place.

Anonymity comes in many different forms. As part of a classification of how this multi-tiered concept is expressed in the classroom, Ray, Downs, Vey, Azmy, and Squires define three separate levels: “complete anonymity (unidentified to everyone), semi-anonymity (anonymous to one’s classmates but not the professor), and no anonymity (everyone can see your true identity)” (Ray, et al., 2006) To preempt any chance of bias on the part of the author that might impact subsequent scoring of graded assignments or exams, the solution needed to be designed for the first level – complete anonymity. In addition to the bias prevention argument, Freeman posits another factor in favor of a greater degree of anonymity in Anonymity and In-Class Learning: The Case for Electronic Response Systems that “Results suggest that anonymity is a critical factor affecting student willingness to participate with in-class exercises. Results also indicate that students’ propensity to engage with in-class questions increases with the degree of anonymity provided to the student in revealing their response.” (Freeman, 2014).

The solution

After much consideration of potential options, including free software such as Microsoft Office Online as well as financially-burdensome multi-user licensing options for Computer Assisted Translation (CAT) tools such as SDL Trados that encourage collaboration amongst translators, the author finally decided on the use of a combination of two applications and one add-on within the Google Drive suite, namely Google Forms, Google Sheets and Form Creator. The Google Drive suite of applications is free for educational and non-profit use, supports multiple users, languages and platforms, and features a growing range of add-ons that enhance the functionality of existing applications. Google Forms is Google’s pseudo-database application used to collect data; Google Sheets a spreadsheet program; while Form Creator is an add-on for Google Sheets that automates the creation of data input and output. Some key advantages of this ad-hoc approach include its cost (zero), optional opt-in user identification (data entry is anonymous by default), ease-of-use (no learning curve for web-based assignment submission via a web form), and output options (both entire assignments from individual students and translation segments from multiple students may be exported in XLS or PDF format, or simply displayed on screen in Google Sheets/Forms).

The process

The process of automating the setting up of a Google Forms file is outlined below. The instructions assume the existence of a free Google account, some familiarity with use of the Google Drive suite of applications and basic Internet skills.

The first step for a faculty member considering the use of the A4C system outlined above is to point their browser in the direction of Google Drive (http://drive.google.com). Once there, they are presented with a file manager interface that may remind them of an early iteration of Windows Explorer.

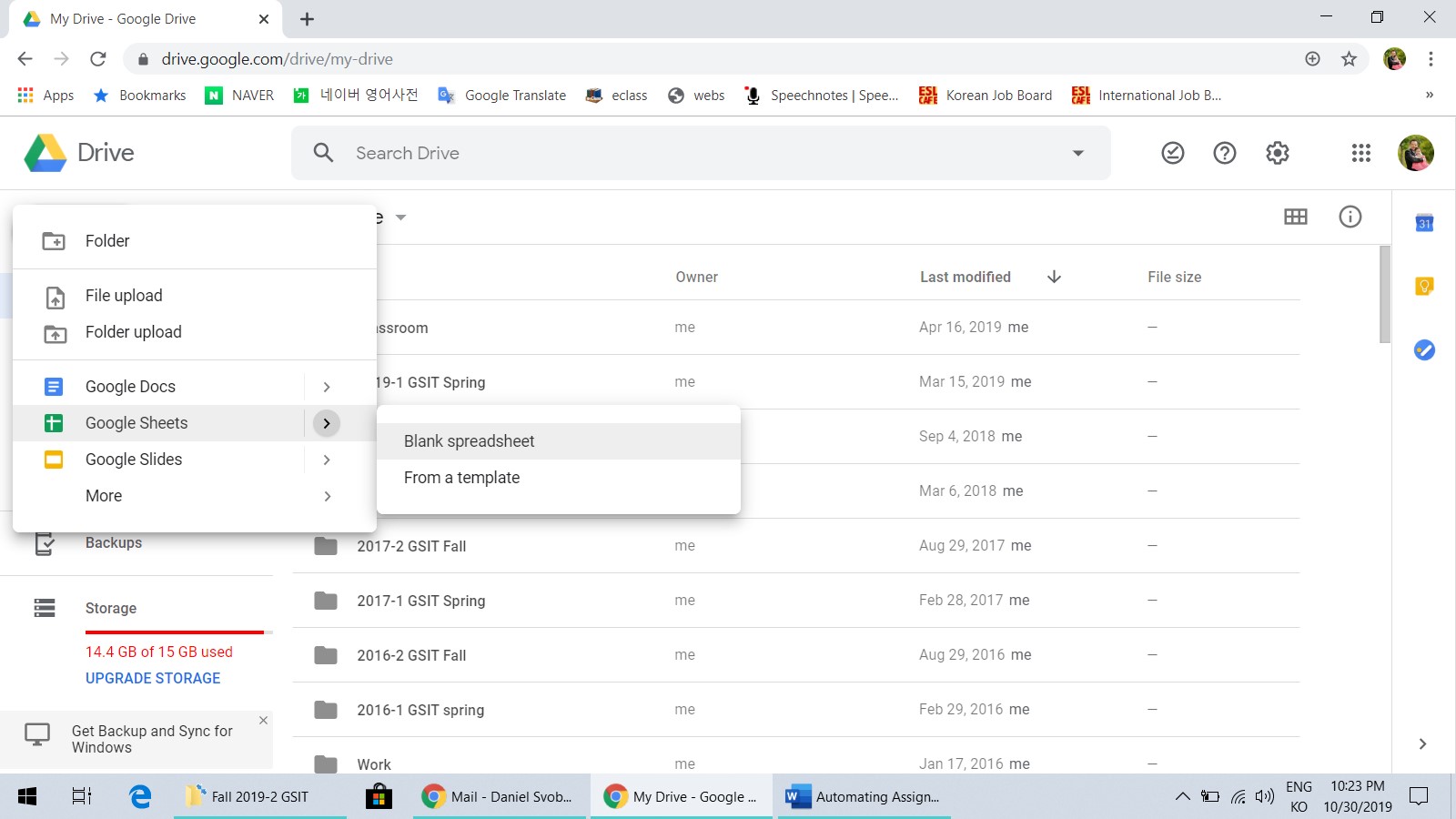

The next step in the process is to create a new Google Sheets spreadsheet.

(Figure 1 – Creating a blank Google Sheets spreadsheet in Google Drive)

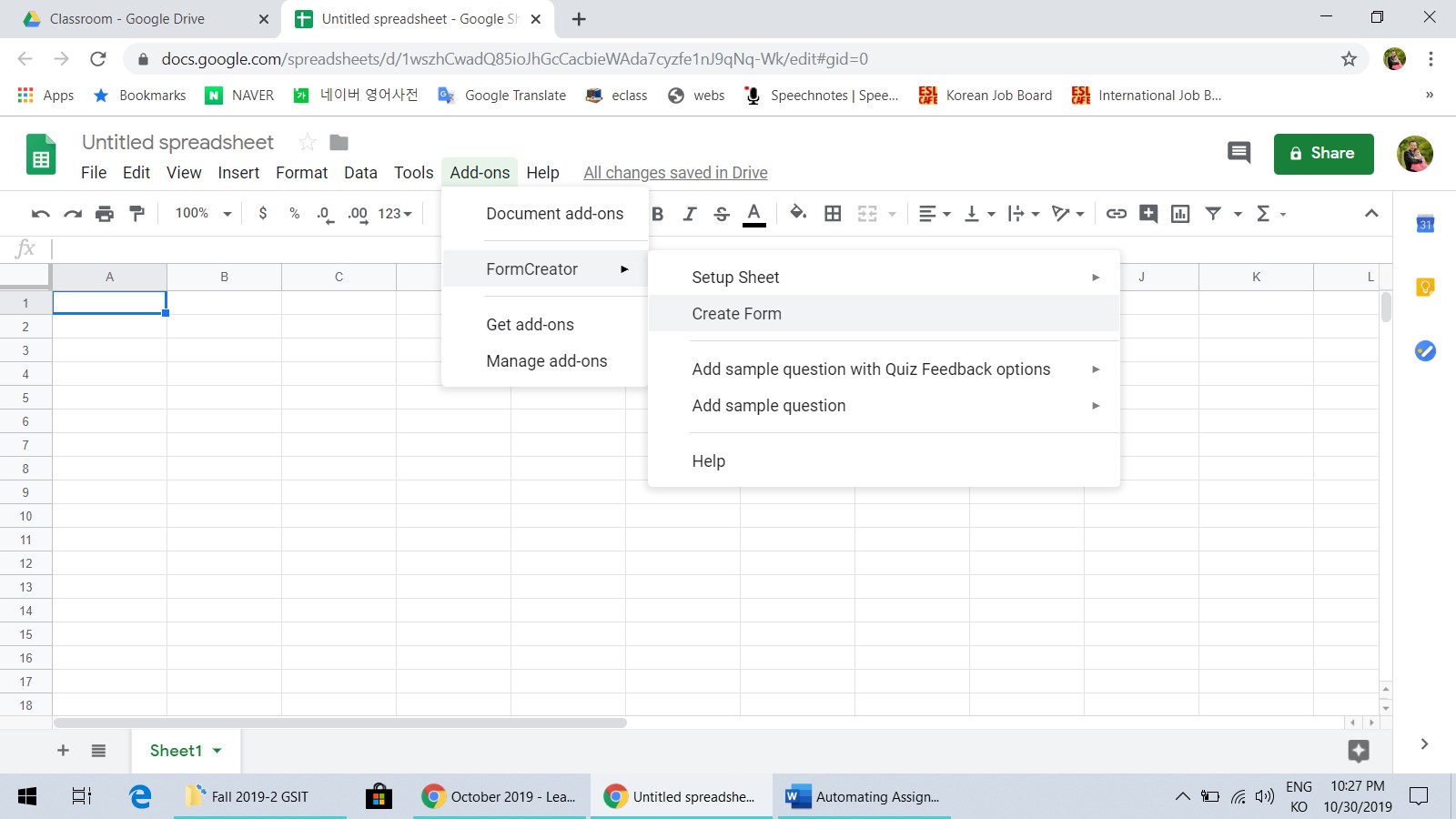

An empty spreadsheet will appear, at which point the Add-ons menu is used to install the Form Creator add-on. The add-on contains multiple menu selections. For the purposes of this paper, select Create Form.

(Figure 2 – Creating a new form using the Create Form function in Form Creator)

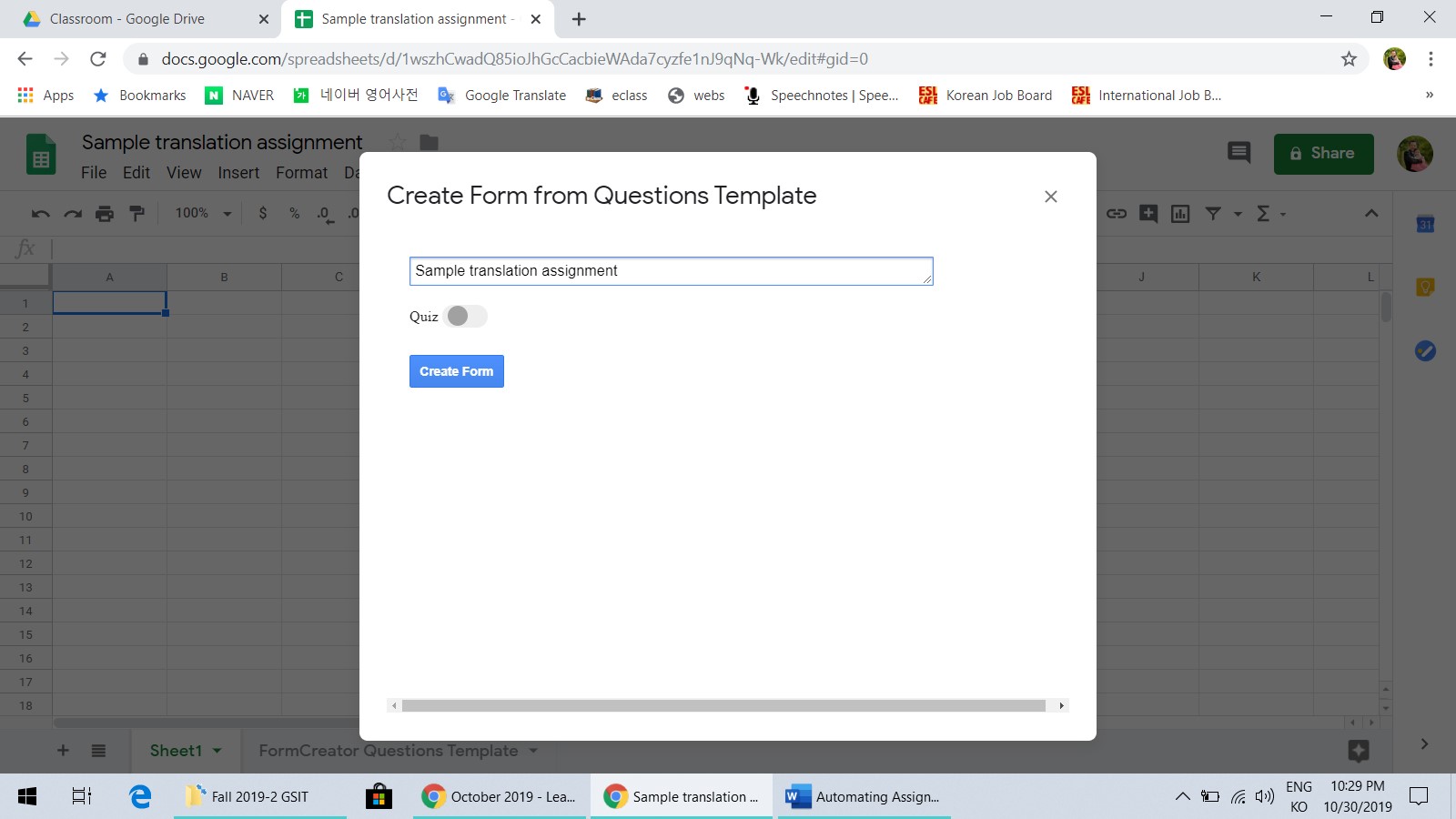

After navigating through several dialog boxes, a new form is created.

(Figure 3 – Navigating the dialog box that automates form creation)

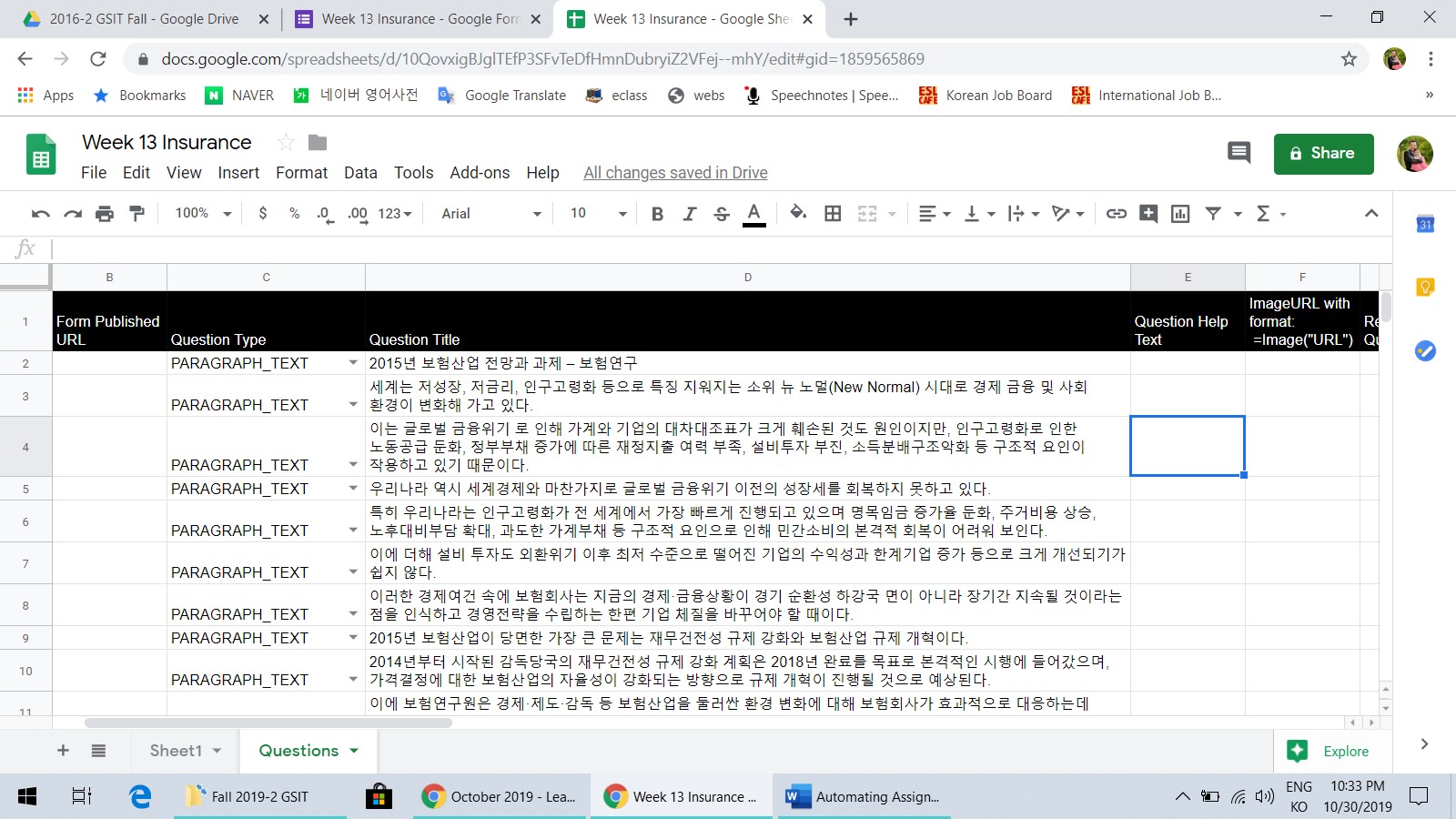

The previously empty spreadsheet is now automatically filled with a variety of different form fields for different data types. Decide on the data format required for the individual assignment. Writing and translation courses will typically require the “paragraph text” data format to enable input of single- or multiple-sentence length segments.

(Figure 4 – Specifying individual questions and data type (PARAGRAPH_TEXT) for each question.

A prompt for each input field (in this case, sentences from the ST) is provided for student convenience and future faculty reference. After the data type and prompt for each data field has been decided, click on the “Create Form” button.

Now, navigate away from the spreadsheet and find the automatically created Google Form in the root folder of Google Drive. You can now click on the Form to edit the fields manually, set a deadline for assignment submission, allow students to edit previously uploaded assignments or require students to login using a Google account for identification, if needed, as well as create a URL shortcut that students can access to upload translations or other written assignments according to the prompts provided.

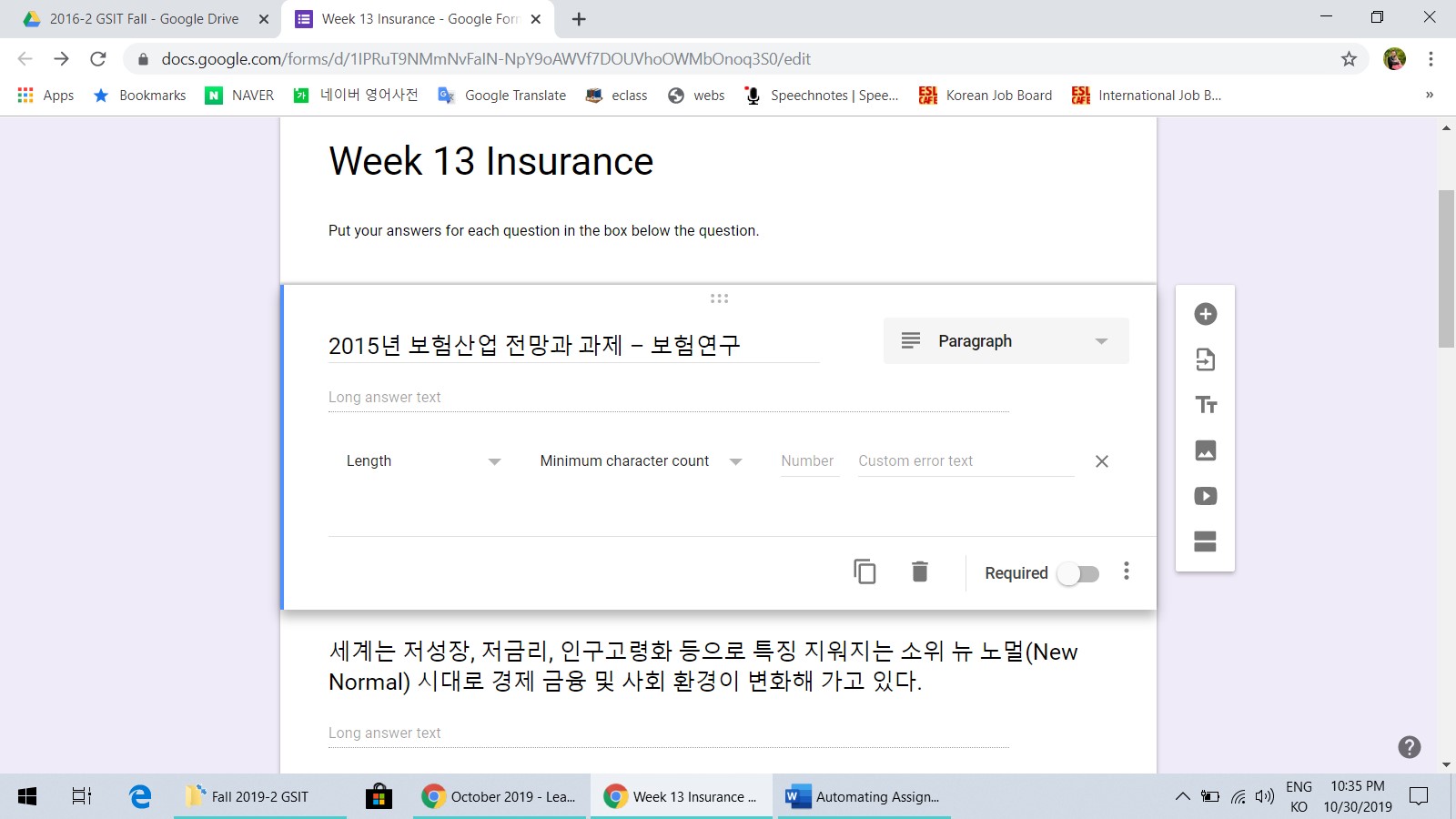

(Figure 5 – Reviewing individual questions manually before posting the form for student assignment submission)

After students have completed the data entry process, faculty can refer to either Google Forms or Google Sheets to review, revise and export student entries. The Google Forms interface provides for two distinct viewing options: all entries from a single student or an aggregated view of all the responses from multiple for a particular prompt.

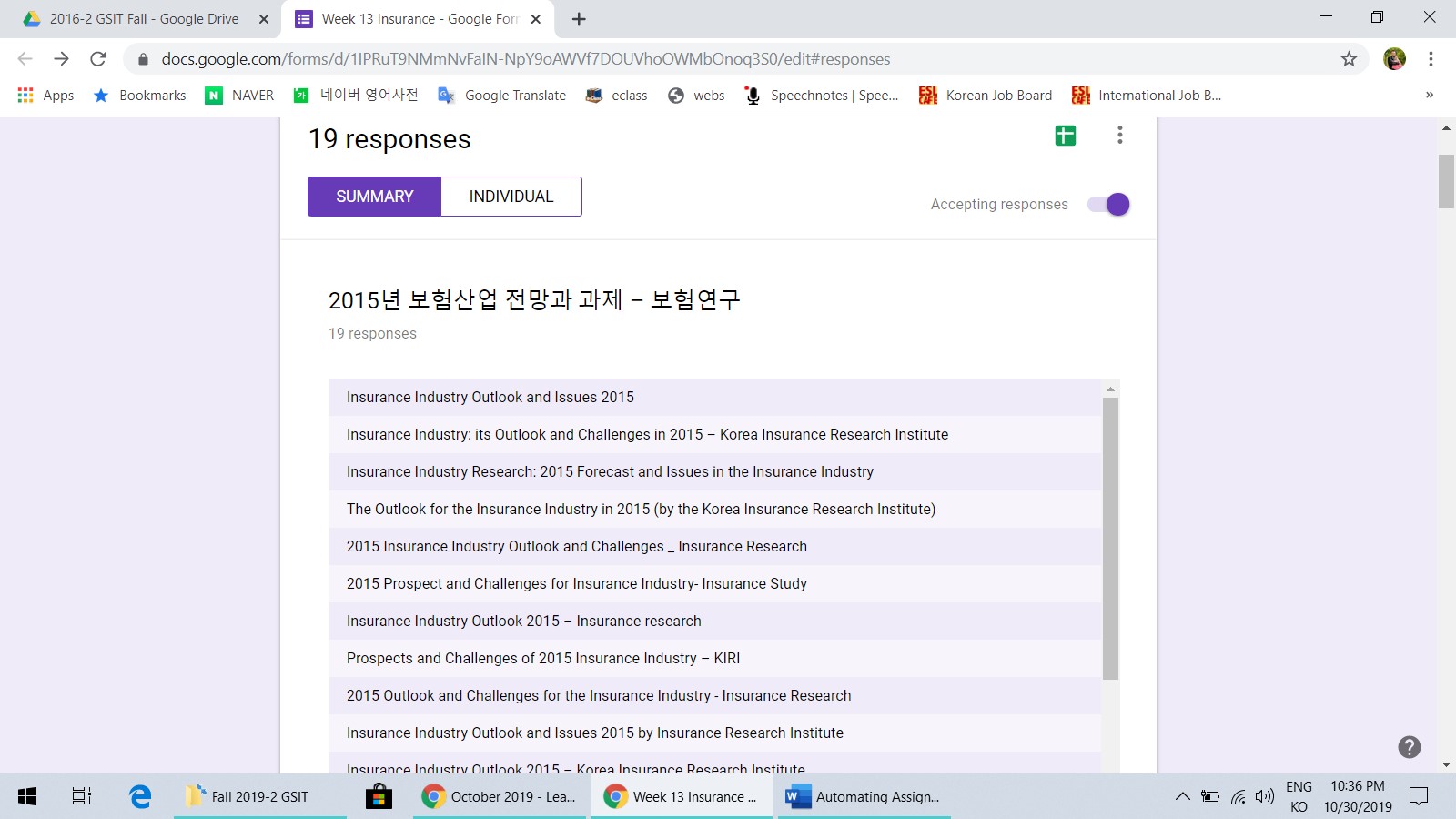

(Figure 6 – Reviewing multiple student answers for the same translation segment)

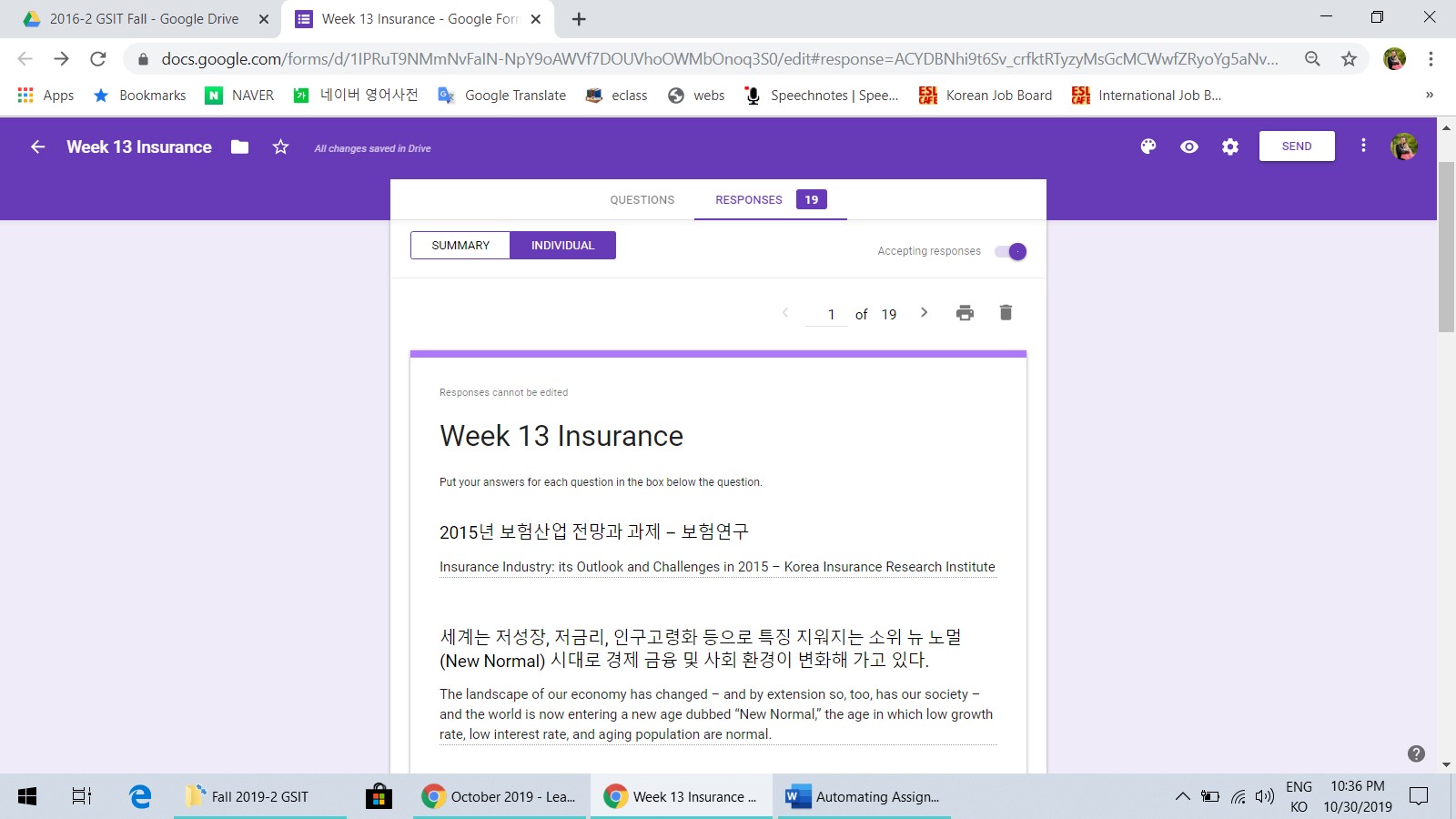

(Figure 7 – Reviewing an entire translation from a single student)

An complete translation of the text from just one student may be of use when focusing on textual coherence and unity as well as the use of transitions, while comparing translations from multiple students allows for a more microscopic view of a wide range of language issues detailed in the following section. Google Sheets presents the student entries in raw form and enables real-time revision of entries, perhaps with the aim of enhancing grammatical accuracy or manually copying a particular chunk of text. In terms of export capabilities, Google Forms allows for PDF export while Google Sheets lends itself to XLS output.

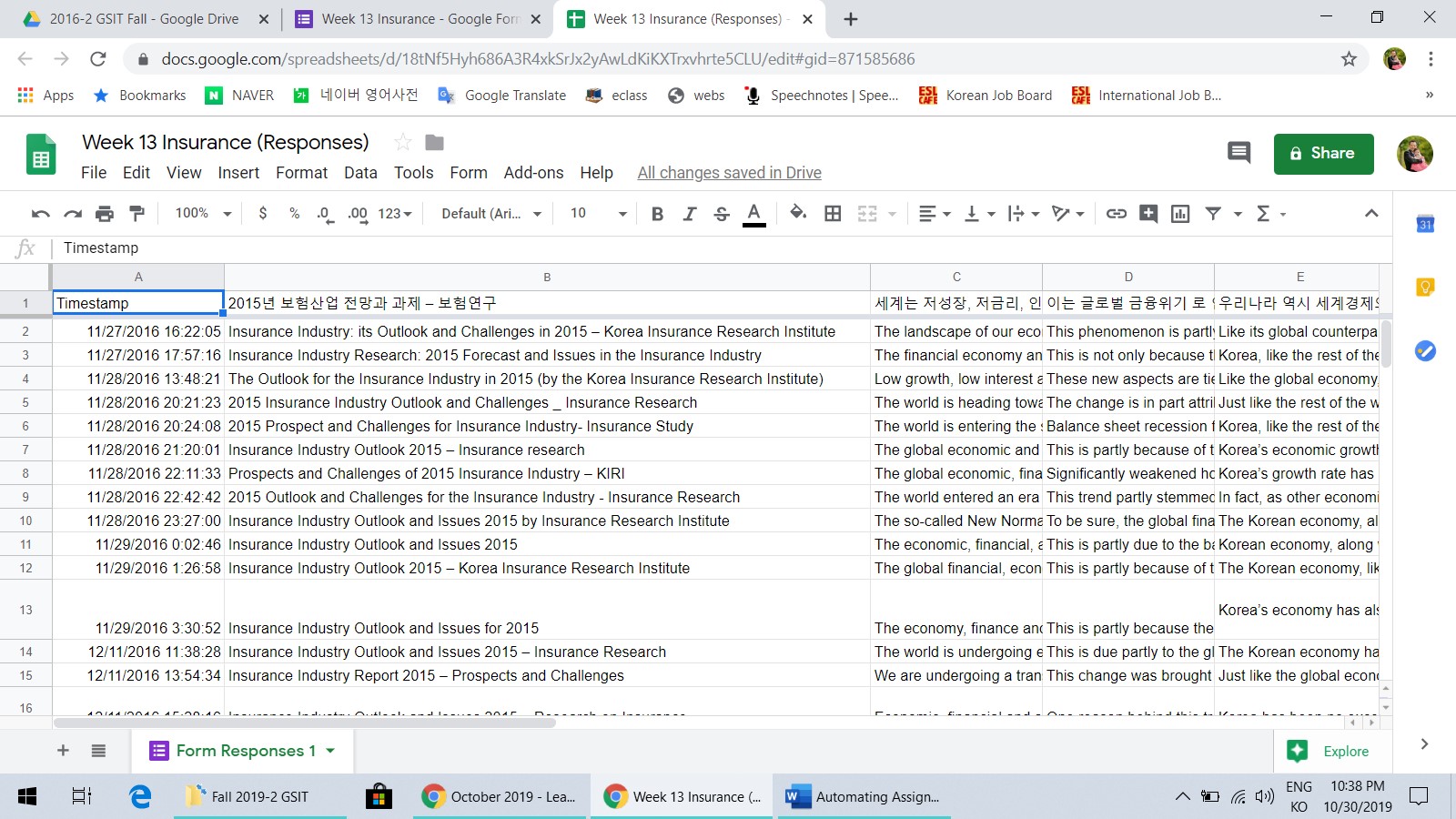

(Figure 8 – Reviewing, revising and exporting individual responses in Google Sheets)

The insights

The anecdotal results from the implementation of the new system included the ability to easily compare translation segments from multiple students (sometimes from different sections of the same course) as well as include the said segments in class materials and feedback, an improvement in the faculty member’s evaluations, increased participation by students in class, and reduced student anxiety stemming from the anonymity of not knowing which students made which mistakes. Both in informal discussions with the author at the end of class and on formal end-of-semester evaluations, students expressed admiration for the complete anonymity of the system as well as its convenience. While students previously made comments along the lines of “I’d prefer if you didn’t look at my translation this week” or “This is not really my best work” when it was their turn to read a segment from their translation, no such anxiety existed under the new system. The author also appreciated the ease with which real-time revisions could be made to student assignment submissions before sharing them with the class as well as the multiple display options (the entire assignment submission from a single student vs. sentence-by-sentence submissions from multiple students) and export formats (namely XLS and PDF formats).

Translation-specific insights

The comparison of sentence-by-sentence submissions from multiple students in the course, in particular, provided insights into a range of translation issues covered. Starting with a bottom up approach, comparing two or more student translations of the same sentence allowed for a closer examination of English formatting conventions and punctuation rules. Common formatting errors in Korean-English translation such as not leaving a space before opening or closing parentheses or using full justification that results in awkwardly large gaps between individual letters or words in the same sentence are immediately visible when placed directly above or below translations with the correct formatting. Likewise, sentences with an overabundance of dependent clauses separated by commas – another frequent mistake made by up-and-coming translators – can be pointed out during in-class feedback sessions and compared to more succinct and grammatical alternatives.

Other types of errors easily pointed out via a comparison of multiple translations include those related to missing or misused articles and prepositions. Students of translation often omit definite or indefinite articles as well as insert them incorrectly in front of plural nouns that do not require them. In the same manner, due to differences in grammatical structure between Korean and English, students will occasionally place a preposition where a postposition would ordinarily be or use the incorrect preposition for a specified location or time.

In terms of word choice, another category of error common in translation, a variety of different options for the translation of a particular word or phrase may be highlighted on screen in the middle of class, chosen from the assignments uploaded by students in the same class or course. The effect word choice has on nuance and register are also made more readily apparent when discrete chunks of translated text are compared. Real-time searches for specific words or phrases in either the source or translated text are easily conducted when the student output is viewed in the native Google Drive web application, or when saved in Microsoft Excel XLS or Adobe Acrobat PDF file format. In addition, decisions made by the translator regarding distinct grammatical choices such as those that involve the use of inversion, active or passive voice, nominalization, and modifiers can be brought to light by faculty members after a review of all student output for a specific sentence in the text.

Perhaps most importantly, however, automated aggregation of student translations for a specific phrase, clause or sentence emphasize the differences in translation approaches adopted by different students for different texts over the course of a semester. These approaches range from direct word-for-word translation that delivers the one-to-one correspondence appropriate for legal documents to more fluid thought-for-thought translation that is typically better suited to literary texts. Even within a specific overarching translation strategy - take thought-for-thought translation as an example – the translator may choose to pursue a foreignizing or domesticating approach that leaves Korean words transliterated in italics or seeks to substitute them with English words that convey a similar meaning or nuance. Comparisons such as these exhibit the broad spectrum of translation faithfulness, namely how closely a translated text follows its original source. Students are often struck by the completely dissimilar, yet equally valid translation strategies pursued by their peers sitting right next to them. Equally interesting to students is how disparate approaches to translations of the same text can yield surprising variations in word count, readability, unity and register.

4. Future research directions

Due to time and workload constraints, this paper depended almost entirely on anecdotal data from the author’s own classes for a description of the original problem, the solution and any insights gained. Such limitations magnify the limited scope and application of the solution adopted. There are a wide range of translation courses at GSIT taught by several dozen faculty, each with their own unique approach to the collection and in-class utilization of submitted assignments. The author hopes to present an abstract of this paper at a subsequent faculty seminar to gather feedback from colleagues and fine tune the ad-hoc system described herein.

Any future research studies would require a clearer delineation of the need for such a system evidenced by quantitative and qualitative student feedback on faculty evaluations across multiple classes taught by different faculty. Moreover, a comprehensive survey of assignment submission methods utilized at other similar institutions specializing in translation both in Korea and around the world might give rise to alternative solutions. If the same system were to be implemented on a pilot basis, a follow-up survey after the implementation of the system could be conducted to gauge faculty and student responses. More specifically, a detailed case study of in-class error correction before and after the introduction of the said system would highlight both its advantages and disadvantages.

Another potential opportunity for further development lies in integration with Google Classroom, a fully featured LMS that educators at all levels can customize to suit the needs of almost any course that involves the submission of written or audiovisual assignments. Google Forms can be tailored to automate assignment collection, give pop quizzes or conduct feedback surveys, all within the confines of the Google Classroom page for a particular class.

Yet another avenue for exploration is the adoption of such automated aggregation in writing classes. Since translation, by definition, involves writing in a target language, there are naturally many areas of overlap between translation courses and composition courses. While the types of mistakes or level of complexity involved in discourse analysis may differ depending on student level and course objectives, the end goal is often the same. Students in both courses hope to produce better-quality effective English writing with fewer mistakes. The author believes that, with appropriate modifications, the system described in this paper could easily be adapted for sentence, paragraph or even essay writing classes. The ability to share both student mistakes and achievements is a clear and present need in a wide range of courses where written assignments constitute a major portion of student grades.

References

Bergstrom, T., Harris, A., & Karahalios, K. (2011). Encouraging initiative in the classroom with anonymous feedback. IFIP Conference Proceedings on Human-Computer Interaction, 627-642. Retrieved October 27, 2019 from http://social.cs.uiuc.edu/papers/pdfs/bergstrom-interact2011.pdf

Freeman, M., Blayney, P., & Ginns, P. (2006). Anonymity and in class learning: The case for electronic response systems. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 22(4).

Latham, A., Hill, N. S. (2014). Preference for Anonymous Classroom Participation: Linking Student Characteristics and Reactions to Electronic Response Systems. Journal of Management Education, 38(2), 192-215.

Ray, K., Downs, D., Vey H., Azmy K., & Squires, A. (2014). Anonymity and Classroom Participation. Classroom Technology Report White Paper.

Sullivan, P. (2002) “It’s Easier to Be Yourself When You Are Invisible”: Female College Students Discuss Their Online Classroom Experiences. Innovative Higher Education, 27(2), 129-144.

Weaver, R.R., Qi, J. (2005). Classroom Organization and Participation: College Students’ Perceptions. The Journal of Higher Education 76(5), 570–601.

Wilde, O. (2003). The Happy Prince & Other Tales. Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. New York, NY: Collins.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Content-based Instruction: Application of Knowledge of Manual Camera Settings

Ed Topliffe, South KoreaAn Aggregated Automated Anonymized Assignment Collection (A4C) System for Translation Classes

Daniel Svoboda, South KoreaUsing Online Collaborative Writing to Illustrate Research Skills

Richard Prasad, South Korea