Scaffolding Presentation Skills with Peer Feedback and Assessment

Blanka Pojslová works at Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno, Czech Republic where she teaches Business English and is passionate about feedback and how it can contribute to her students´ language development.

Introduction

Presentation skills are an indispensable part of many ESP and EAP courses, and the methods teachers use to develop these skills in such courses may evolve over time. This article describes the evolution of the methods gradually adopted to develop Business English students’ presentation skills in an undergraduate ESP course. The process started with simple instructions on preparing a PowerPoint presentation on a topic related to the students’ studies and gradually developed into a more scaffolded design. Simultaneously, the primary focus shifted from seeing the presentation as a product to seeing it as an interactive process in which students should be given opportunities to learn from and with each other. This was achieved by gradually incorporating peer feedback, peer assessment, and self-reflection in the course design to complement and enhance teacher feedback and assessment.

The main reason for shifting the focus was the need to engage the students more actively in the processes taking place in the classes in which students’ presentation skills were developed. Involving the entire audience in feedback provision and assessment was believed to draw the experience of delivering and observing presentations closer to real-life situations where there is not usually only one person in the audience (i.e., the teacher) who should have an ultimate opinion about the quality of the presentation but rather it is the entire audience whose voices should be heard and counted. Thus, the teacher’s feedback and assessment were complemented by feedback and assessment from fellow students, thus making the feedback on the presentations more comprehensive and understandable and the assessment more objective and balanced overall.

Background

Feedback is a powerful teaching tool that assists learners in identifying their strengths and weaknesses and improving their understanding and performance. It might take the form of suggestions or comments for improvement that are provided through recognizing the quality of performance (Sadler, 1989). The main purpose of feedback is to reduce discrepancies between a student’s current understanding and performance and the goal of the work (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Feedback can be conceptualized from the perspective of Sociocultural Theory originating in the work of Vygotsky (1978), who views learning not as an individual activity but one with social and collaborative dimensions which is mediated through social interactions with an expert, between learners, or among more capable peers.

Learning, including language learning, can take place within a learner’s zone of proximal development (ZPD) with the help of scaffolding. The zone of proximal development is a theoretical construct defined as a state between a learner’s current levels and potential levels of development, and scaffolding is supportive behaviour by which an expert or a peer can help a novice learner achieve the developmental level of independent functioning, at which point the scaffolding is removed (Wood et al., 1976, p. 90).

Context

Presentation skills taught in the four-semester Business English course are systematically developed in the second and third semester of this course. In the second semester, students deliver an individual presentation in which they mediate a chosen text dealing with a topic from their academic field. This presentation is given during the semester in class and becomes part of their end-of-course oral exam at a B2 level of CEFR. In the third semester, students deliver a group presentation to share the results of a team project they undertook during the semester.

In both cases, students are encouraged to provide peer feedback and peer assessment of their colleagues’ presentation skills, using ICT tools to make the most of the time available in the 12-week course. The use of ICT tools was further accelerated when the Covid-19 pandemic necessitated online learning, and some of these tools became very useful in the post-Covid period after we returned to face-to-face classes.

Scaffolding peer feedback and assessment over time

Where we started

Before the introduction of the B2-level exam in the second semester of the four-semester Business English course, presentation skills were developed as one of the assignments students were given to complete the course. Before delivering presentations, students were given class input on delivering academic presentations, which consisted of group discussions, pair and individual work regarding presentation structure, signposting language, and tips for an effective presentation accompanied by practice in pairs or in front of each other.

Before each class presentation, students were divided into peer groups and given evaluation forms to assess the presenter. After the delivery, the students were asked to provide short written feedback on the presenter’s strengths and room for improvement regarding his or her presentation skills together with an assessment of the presenter’s performance by completing a pen-and-paper evaluation form covering assessment criteria. This form was also used by the teacher.

After the class presentation, each peer group gave immediate oral feedback on the presenter’s performance, which was complemented by the teacher’s oral feedback. Finally, the presenter was given the evaluation forms with the assessment and feedback from individual peers and the teacher to see how they assessed his or her performance and which recommendations the presenter might follow in the future. The presenter thus received immediate peer and teacher oral feedback as well as peer and teacher written feedback and assessment, though no overall score was given. In fact, the formative nature of this assignment, which had no effect on the final grade, did not require an overall score.

Covid-19 experience

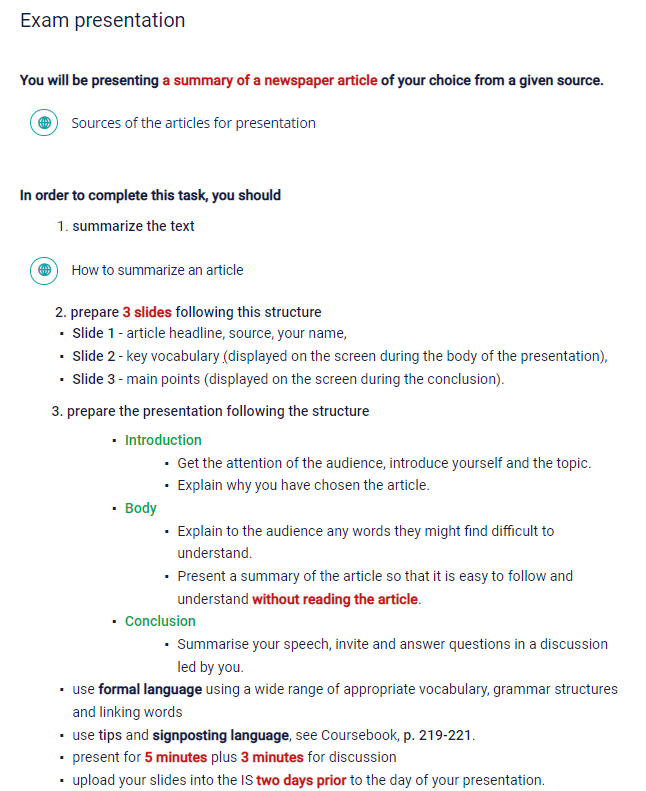

After the introduction of the B2-level exam in the second semester, which coincided with the Covid-19 lockdown and transition to 100% online synchronous teaching, the design had to be adapted to this mode of teaching and learning. To compensate for less extensive class input on delivering presentations in online classes, mainly caused by time constraints and limited space for practice in pairs and in front of each other, a practice presentation was introduced. Students were asked to prepare their practice presentations and record them in video format following the exam presentation guidelines. Figure 1 illustrates these guidelines.

Figure 1: Presentation guidelines

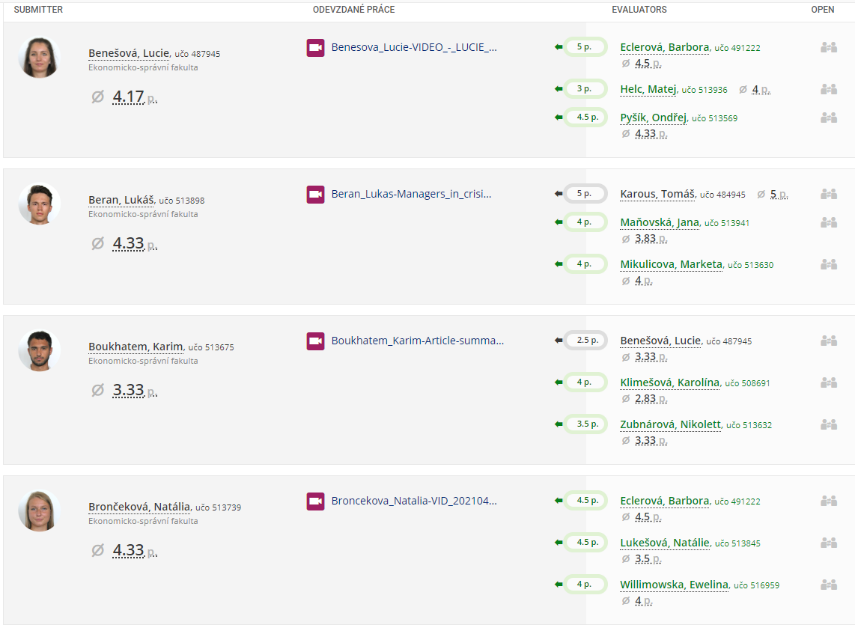

The recorded practice presentations were then submitted for computer-mediated peer review carried out using the Learning Management System (LMS) developed and fully supported by the university. The LMS offers the Peer Assessment application which facilitates asynchronous peer review. The application randomly assigns each student three peer practice presentations for peer review, and in return each student receives three peer reviews from their colleagues. In this case, the peer review consisted of peer assessment using exam assessment criteria for presentations and peer feedback in the form of comments on the presenter’s strengths and room for improvement. Figure 2 illustrates the Peer Assessment application.

Figure 2: Peer assessment application in the Learning Management System

Following the computer-mediated peer review of the practice presentations, students then prepared their exam presentations, reflecting the peer feedback and assessment they received from their peers in the final presentation. These exam presentations were delivered synchronously in Zoom classes with peer and teacher feedback and assessment provided immediately after the delivery of the presentation. However, this time it was necessary to give an exam score for the presentation.

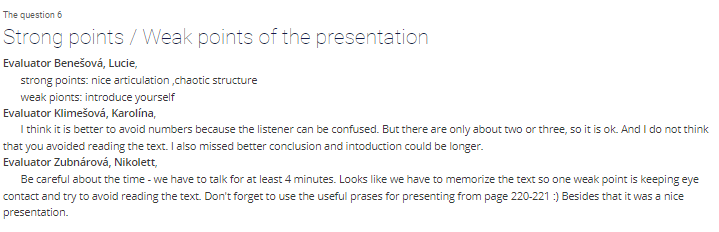

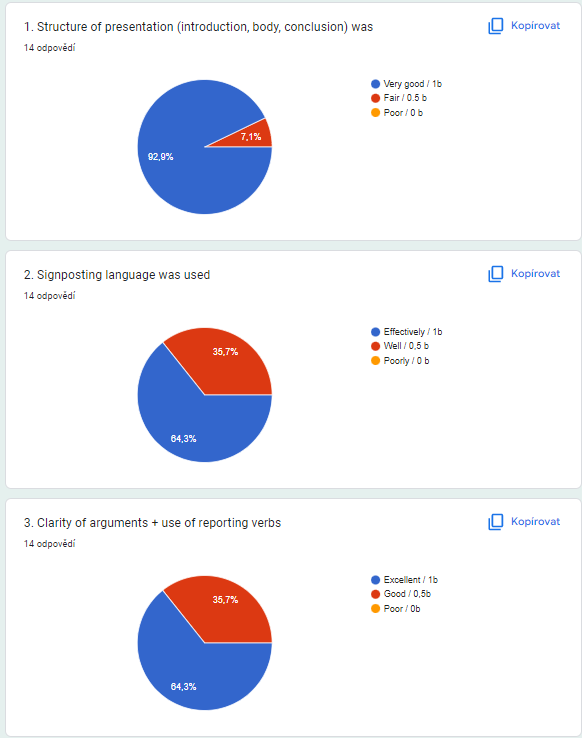

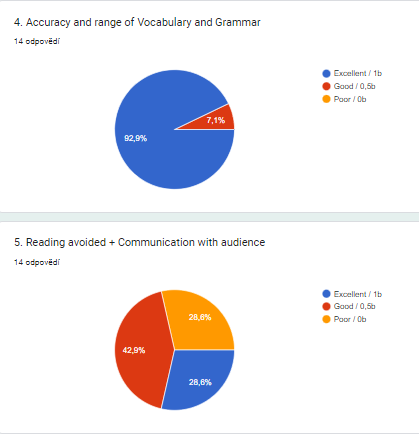

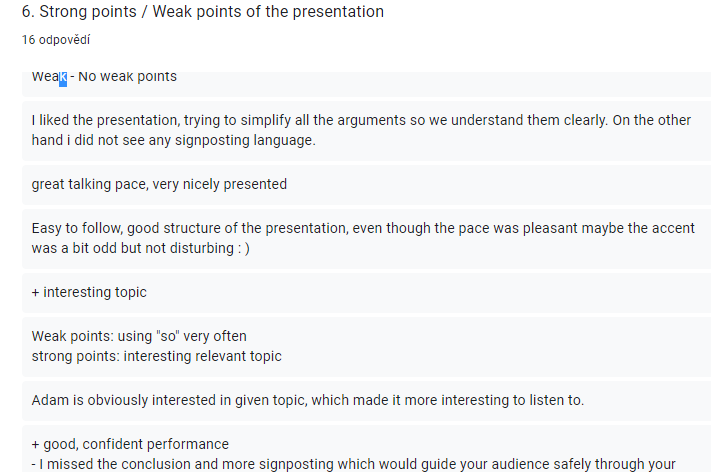

In order to determine the exam score for the presentation while engaging the entire presentation audience, Google forms, which are part of the free, web-based Google Docs Editors suite, were used. Before each exam presentation, the other students received a link to the given presenter’s Google evaluation form and were asked to complete it by giving their feedback and assessment once the exam presentation and Q&A session had finished. The aggregated results of the individual peer and teacher assessments together with short written feedback were shared with the presenter via the Google form after oral peer and teacher feedback was given. The exam presentation score was then calculated from the individual peers’ scores and the teacher’s score and later added to the score of the second part of the oral exam taken at the end of the course. An example of combined peer–teacher assessment and feedback is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Example of combined peer–teacher assessment and feedback

Back in the classroom

After returning to face-to-face classes, the design for scaffolding the development of presentation skills was further enhanced and received its final form. This form strove to combine the features of the previously used design while adding one more form of peer response to the student’s performance. The pre-Covid design, which included extensive class input on delivering presentations along with peer assessment and feedback after the exam presentation, was still used and further enriched by adding the video practice presentation with computer-meditated peer review and online peer–teacher feedback and assessment via Google forms used during Covid classes to share peer and teacher written feedback and calculate the final exam presentation score.

Moreover, to take advantage of being back in the classroom, an additional form of peer feedback was implemented. After the students received peer reviews on the video practice presentations through the LMS application Peer Assessment, they were instructed to deliver the same practice presentation in class reflecting the feedback they were given. In class, students gave their practice presentations in groups of three and commented on each other’s performance immediately, focusing on aspects of presenting that were absent or were not so prominent in the video presentations, such as body language, audience engagement, and Q&A session. The presenters also thereby experience the presence of a real audience while coping with anxiety, stress and other pressures entailed by face-to-face presentations.

Having received a plethora of peer feedback in different forms while also providing the same feedback to their peers, students became closely familiar with the assessment criteria and exam presentation requirements and expectations and thus better prepared for their exam presentations. For the remainder of the semester, students delivered their exam presentations in class while being assessed jointly by the teacher and peers who were present in class on the day of their presentation. For this in-class assessment, the students and the teacher used the Google evaluation forms in the same way as during online classes.

Conclusion

Developing presentation skills in a foreign language in an academic context is often a daunting task for undergraduate students. The assistance given to them in their zone of proximal development might be provided not only by the teacher but also by their peers in the form of peer feedback and assessment. Thus, the students not only receive feedback but also provide it, and this dual role can further contribute to developing their knowledge and skills toward the desired goal (Mory, 2004).

Peer assistance might take different forms and can be scaffolded for both givers and receivers of this assistance. In this case, it started for the givers by providing computer-mediated peer feedback and assessment, which furnished students giving feedback and assessing their peers’ video presentations with sufficient time to return to class materials when evaluating the extent to which presenters had met expectations. The second form of peer response to the practice presentations took place orally in class within small groups. This time the response was enhanced by peers’ experience with providing feedback in the computer-mediated environment and familiarity with the expectations and assessment criteria, which is considered crucial for the effectiveness of peer feedback (Saito, 2013). Finally, when assessing the exam presentations in class, students have already had practice with this process, which contributed to the acceptance of combined peer–teacher final scores for the exam presentations by the presenters as peer assessment strongly correlates with teacher assessment (Ahangari et al., 2013).

On the other hand, the presenters benefited from this gradual support in many ways as well. First, when recording the practice presentation, presenters had the opportunity and time to reflect on their performance and undertake revisions. While delivering the same practice presentation in class to a small audience consisting of two peers, they focused more on presentation skills rather than the content of their presentations, as this aspect had already been practised in their video presentations. The exam presentation then combined both aspects—content and presentation skills. The familiarity with the expectations established through practice presentations and the dual role of being a feedback giver and receiver equipped the presenters with sufficient support to function independently when delivering their exam presentations (Susan, 2012; Kusumayanthi, 2022).

References

Ahangari, S., Rassekh-Alqol, B., & Hamed, L. (2013). The Effect of Peer Assessment on Oral Presentations in an EFL Context. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 2(3), 45–53.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Kusumayanthi, S. (2022). The Effect of Peer Feedbacks on Students’ Speech. English Journal Literacy UTama, 7(1), 603–611.

Mory, E. H. (2004). Feedback research revisited. In Jonassen, D. (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp.745–783). Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah.

Sadler, R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119–144.

Saito, Y. (2013). The value of peer feedback in English discussion classes. In N. Sonda & A. Krause (Eds.), JALT2012 Conference Proceedings (pp. 430–438). Tokyo: JALT.

Susan, O. (2012). Enhancing Peer Feedback and Speech Preparation: The Speech Video Activity. Communication Teacher, 26(4), 224–227.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem-solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Scaffolding Presentation Skills with Peer Feedback and Assessment

Blanka Pojslová, the Czech RepublicFeedback Time, The Time of Learning: Guiding a STEM-oriented Presenter in Learning to Self-reflect

Eva Rudolfová, the Czech Republic;Marcela Sekanina Vavrinová, the Czech RepublicEnhancing Teacher Feedback on Student Writing with SkELL

Blanka Pojslová, the Czech Republic