- Home

- Various Articles - SEN

- How to Bring English as a Foreign Language to Hospitalized Primary School Students

How to Bring English as a Foreign Language to Hospitalized Primary School Students

Giorgia Fattori works as an English teacher in public primary schools in Italy. She is focused on foreign language teaching and learning in meaningful contexts and in-hospital schooling. She has written an article based on research about storytelling in EFL acquisition in preschools that will be published in SeLM – Scuola e Lingue Moderne. Her current professional interest is foreign language teaching and learning through a social lens that embraces and connects us in the human experience and extends learning beyond the walls of the classroom. She enjoys working with teachers and professionals in the educational field from all over the world. Email: giorgia.fattori93@gmail.com

A new concept of health

Humanising the health care system means caring for patients from a holistic point of view (García, 2014; March, 2017). This concept has its roots in the 1946 World Health Organization (WHO) definition of “health”: health is a state of complete well-being (physical, psychological, social) and not merely the absence of disease. This has led to the development of a multidimensional and broader concept of health which is now characterized as being determined by biological, psychological and social factors (Schwartzmann, 2003; Molina 2020). Therefore, the goal of healing is not only combating disease but also working on quality of life by promoting global well-being (Terris, 1983; Aixa, 2004).

Why in-hospital schooling is part of the healing process

With this new, expanded concept of global well-being, at its core, in-hospital schooling serves as a bridge between the hospital and the school, guaranteeing emotional, social and cognitive support during illness or hospitalizations. It ensures children’s right to health and education (Modenini et al., 2012). It helps normalize the hospitalisation process, by constructing as familiar a learning and social environment as possible, even though the child’s life has been interrupted by an illness or disease (Axia, 2004; Martinez Soto et al., 2013). In-hospital schooling reduces school absenteeism (Grau, 2013) and the negative impacts of the disease, especially within the emotional sphere of the child and his/her family (De la Huerta et el., 2006; Espada et al., 2012; Grau et al., 2012). In addition, Bernales (2019) has proved how a chronic disease and its treatments (e.g., chemotherapy) has a deep cognitive impact on the learning process which characterizes natural child development. The author claims that, within the socio-constructivist framework, it is essential to offer emotional support and positive learning experiences to hospitalized children, by seeing them as students and not just ill patients. Within this context, the objectives of the in-hospital teacher are to promote learning and acquiring new skills, while at the same time, nurturing their students’ physical and emotional well-being. As Lizasoain (2021) claims, this support helps ill children build the essential resilience to fight the disease.

A few insights on in-hospital teaching and learning

As stated above, one of the main goals of in-hospital schooling is building a bridge between the child’s school, the hospital, as well as the other schools or institutions of the surrounding area, in order to promote awareness about paediatric diseases and hospitalized children. This could be accomplished by planning activities through which the students create artwork that they can share with their classmates and teachers at school, in order to document their learning process during their hospital stay (Capurso, 2001). It is also important that the children leave a mark, through their work, in the hospital (e.g., posters, drawings). This helps make it more familiar and comforting, therefore less scary and unknown, in case of a second hospitalization (Kanizsa et al., 2009). It is also essential that teachers pay careful attention to the social sphere of the students by planning activities where children can gather, get to know each other and interact in accordance with their health needs and restrictions (Kanizsa et al., 2009). In addition, it is essential to plan activities that build on what children already know and can do, as the starting point to develop new skills. This helps bolster self-esteem, as well as create positive associations with their stay in the hospital (Grau, 2013; Calvo, 2017). In other words, in-hospital schooling is a safe, positive, nurturing place where children are considered as children and students, not only as ill patients.

Since in-hospital teachers are part of the healing process, they are also part of the multi-professional network that supports the ill child and his/her family. They have to work as a team with the healthcare professionals, volunteers and other teachers in the hospital. They have to cooperate with the family and the teachers of the school of origin (Grau 2013; Lizasoain, 2021). In-hospital schooling follows the child’s health needs in accordance to his/her medical treatments. For example, some students are mobile, while others must remain lying down or are isolated. Because of this, teachers have to plan flexible activities that fit a variety of contexts and situations. There are a multitude of elements that must be considered: interests of the individual children, their skills and skill level, evolving physical and emotional needs and limitations. The teacher must also keep in mind that in this educational context, inclusion is a necessity (Kanizsa et al., 2009). From a methodological perspective, this is favoured by a playful approach. By using methodologies that guarantee flexibility in how students access material and allowing them to show what they know and what they want to learn, teachers can better meet their psycho-affective needs (Capurso, 2001).

Foreign language teaching and in-hospital schooling: theoretical references

As outlined above, in-hospital teaching requires putting careful consideration on the psycho-affective aspects of the learning process. Therefore, teaching foreign languages in an in-hospital school can be theoretically supported by the approaches, methodologies and research in educational linguistics that stress the role of psychological and social factors, like emotions, in language learning and acquisition (Freddi, 1994; Schumann, 1994; Cardona, 2010; Fabbro, 2018). The Natural Approach by Krashen and Terrell (1983) fits in this humanistic perspective of language teaching and learning. This approach emphasises the need of acquiring, rather than learning, a foreign language in authentic and motivating communicative contexts. For young learners, this can be carried out by having them experience the language through many different types of daily activities (Daloiso, 2009). The activities are centred around a specific topic and have the important role of exposing learners to the related key vocabulary and structures, encouraging students to use and re-use them in different ways and meaningful contexts (Balboni et al., 2001; Masoni, 2016). Krashen and Terrell (1983) stress the importance of offering comprehensible language input, in order not to block cognition with the affective filter. By scaffolding the language, teachers help students to understand and use the target language through linguistic and non-linguistic communicative strategies (Daloiso, 2009). As can be deduced, the affective filter concept plays an essential role in in-hospital language teaching and learning. Its activation with young learners can be avoided by using the target language as a vehicle to play (Freddi, 1990). It is also essential to understand the natural language learning curve of students, including the initial silent-period that EFL young learners can experience. This way, at first, language acquisition must focus more on comprehension rather than production (Daloisio, 2009). Lastly, storytelling through storybooks, thanks to their linguistic and non-linguistic characteristics, guarantees young learners an enjoyable and inclusive approach to experience foreign languages (Cameron, 2001; Daloiso, 2009; Costenaro, 2012; Ellis et al., 2014; Masoni, 2016).

Key strategies for flexible foreign language teaching

This article is based on a teaching experience that took place in “San Bortolo” hospital in Vicenza (Italy). The paediatric ward of this hospital includes a general paediatric care ward, (where children with different diseases are hospitalized) and a paediatric surgery ward. The hospitalizations last on average from three to ten days and there are a great number of children with chronic diseases who must undergo recurring day-hospital treatments. Therefore, language teaching had to be planned with a high level of flexibility due to the short and recurring hospitalizations. Because of Covid restrictions, teaching was mostly individual or could only include children in the same room. When possible, a puppet called Spotty, who only spoke English, was used in order to make English use meaningful and emotionally engaging. Spotty, and his English magic box, would help the teacher speak mostly in English during the activities and motivate students to speak in English. In the English magic box students could find a variety of materials such as storybooks, board games and art and craft activities to choose from.

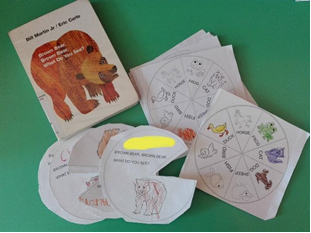

Storytelling, through books, was an important part of activities to help bring English to life with younger students. As an example, Little green peas, a big book of colors by Keith Baker was used to talk about colours. Firstly, students would pick objects of different colours from a bag, to introduce the key vocabulary of the story. Secondly, Spotty would read the book, encouraging students’ participation in order to have them repeat the key words. Then, the teacher would arrange different activities to practice the new vocabulary. In this case, she would propose to make and play Memory or Bingo of colours, listen to and sing songs about colours, and play digital games related to the topic. Mix It Up by Hervé Tullet was also the perfect input to play and experiment with paint and watercolours. Colours and animals were also the main topics of the storybook Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see? by Eric Carle. In this case the teacher and the students played with animal sounds to introduce the key vocabulary and build a wheel of animals, as you can see in the picture, following the story lane.

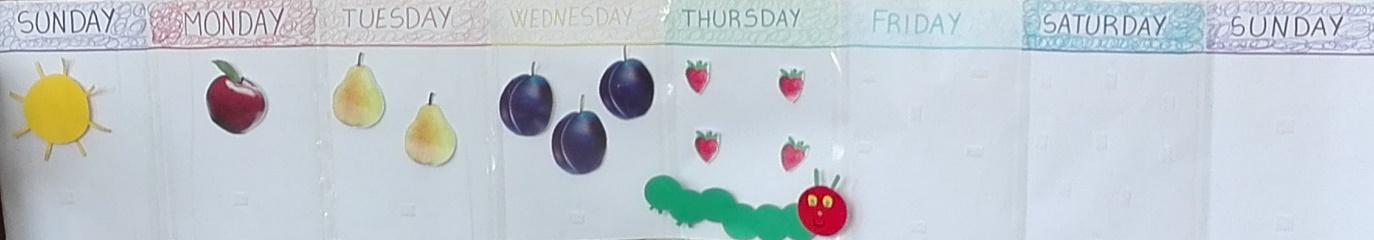

Another well-known storybook was The very hungry caterpillar by Eric Carle. This book was used to talk about food, numbers and days of the week. Firstly, the teacher would introduce a puppet of the tiny caterpillar and, with its help, she would read the story encouraging students’ verbal and non-verbal participation. As you can see in the picture, this story could also be told by using a board with the days of the week on it and having the students stick on the pictures of the foods that the caterpillar eats each day. This can encourage counting and repeating the new vocabulary.

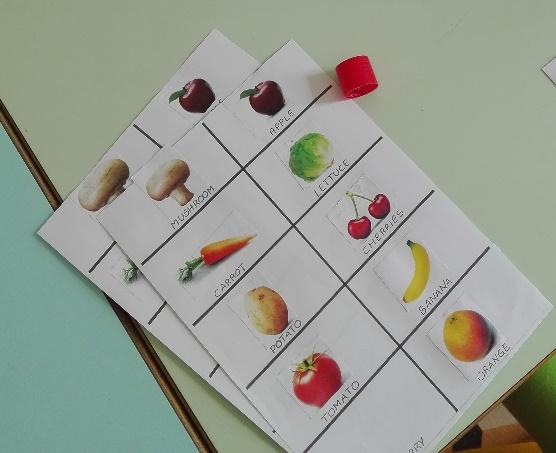

Other activities related to this story, were making and playing Memory or Bingo of food (as you can see in the picture), listening to and singing songs about the days of the week or numbers, creating a book of the story with the shape of the caterpillar and playing digital games related to the main topics.

With older students Spotty would mostly propose famous board games such as Bingo, Domino, Memory, Guess Who and Battleship. Students were given substitution tables about the linguistic structures needed for the game in order to guide their participation and interaction in English. As an example, they would use picture dictionaries about physical description to play Guess Who. The teacher would also work on famous English songs that the students liked or videos related to their interests (e.g., football) to learn the related vocabulary. For older students it was also very important to have a calendar to keep track of time during hospitalization. The teacher would help them build this calendar in English so they could leave a mark in their room and review the vocabulary and structures related to days, months, seasons, numbers and time.

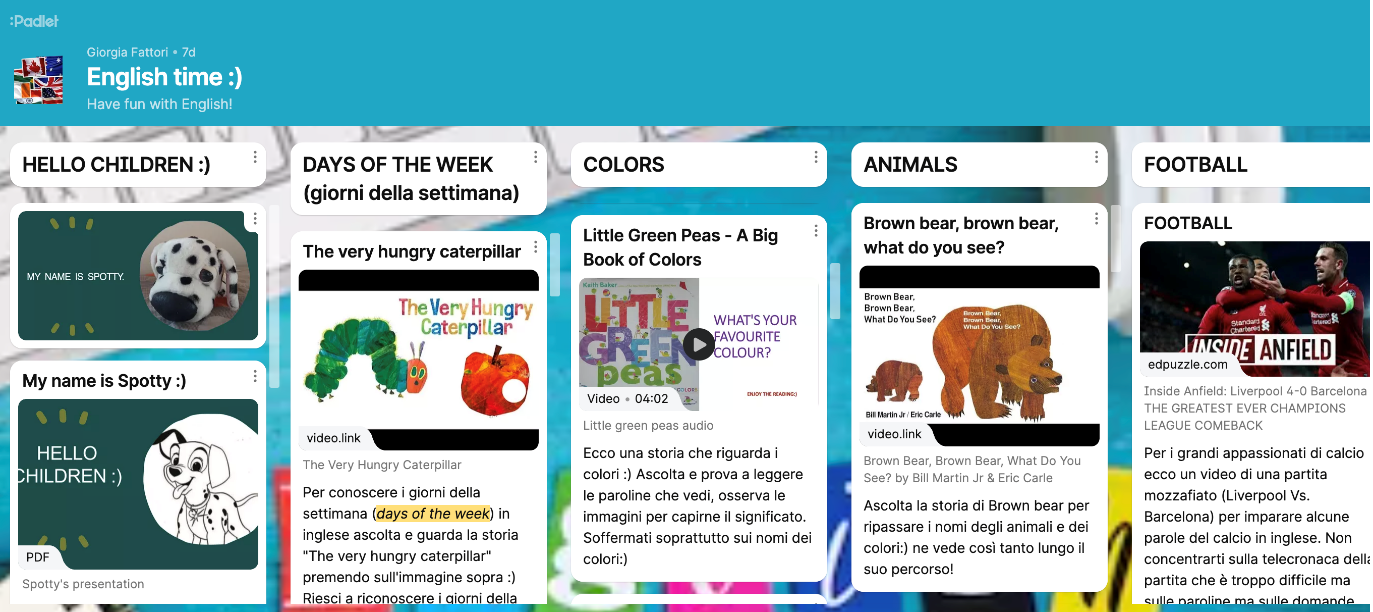

In conclusion, the use of varied activities and strategies, as described above, helped students access the materials in different ways, according to their individual interests, needs, and physical abilities. The activities related to one topic could be linked together in case of longer or recurring hospitalizations, but could also be proposed separately in case of shorter stays. The activities could easily be adapted to cover a wide age range (primary school level: 6-11 in Italy) including single or group work, according to the students’ age and health needs that almost always were not known in advance. Sharing all the digital games, videos, songs and stories with parents and students, through the platform “Padlet,” helped extend the ‘lesson’ time for English throughout the day (see picture below).

Most of the activities included art and craft projects. These were extremely important to make children’s hospital rooms more familiar and cosier, as well as to strengthen the relationship with their teachers and classmates at school. Sharing work that the children made during in-hospital schooling, is significant for a variety of reasons. It helps strengthen the tie between the hospital schooling and the school, keeping students more connected with their friends and teachers and keeping the children at school connected with the hospitalized child. In addition, it helps create a more fluid transition between hospital stays and returning to school which is an important goal to work for since the first day of hospitalization. However, creating and sharing work with the student’s classmates and teachers is also extremely important in order to have the child be proud of the work he/she has done. This means treating and making him/her feel as a school student and child and not a sick child; in other words, taking care of her/him in terms of global and broad well-being.

References

Axia, G. (2004). Elementi di psico-oncologia pediatrica. Carocci Faber.

Balboni, P. E., Coonan, C. M., Ricci Garotti, F. (2001). Lingue straniere nella scuola dell’infanzia. Guerra.

Baker, K. (2014). Little Green Peas: A Big Book of Colors. Simon & Schuster.

Bernales,C. (2019). El aprendizaje de los niños hospitalizados con cáncer. Revista de educación, (24), 1-5.

Calvo, I. (2017). La pedagogía hospitalaria: clave en la atención al niño enfermo y hospitalizado y su derecho a la educación. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 23, 33-47.

Cameron, L. (2001). Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge University Press.

Capurso, M. (A c. Di). (2001). Gioco e studio in ospedale: creare e gestire un servizio ludico-educativo in un reparto pediatrico. Erickson.

Cardona, M. (2010). L’approccio cognitivo-emozionale e il visconte dimezzato. In F. Caon (Ed.), Le lingue di Babele. Facilitare l’apprendimento dell’italiano L2 e delle lingue straniere. UTET Università.

Carle, E. (2002). The very hungry caterpillar. Puffin books.

Carle, E. (2020). Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What do you see?. Puffin books.

Costenaro, V. (2012). Storytelling linguistico-acquisizionale: una proposta per favorire l’acquisizione spontanea dell’inglese LS nei bambini. In M. Santipolo (Ed.), Educare i bambini alla lingua inglese. Teoria e pratica dell’insegnamento dell’inglese nella scuola primaria e dell’infanzia. Pensa multimedia.

Daloiso, M. (2009). La lingua straniera nella scuola dell’infanzia: fondamenti di glottodidattica. UTET Università.

De la Huerta, R., Corona, J. y Méndez, J. (Enero-Marzo 2006). Evaluación de los estilos de afrontamiento en cuidadores primarios de niños con cáncer. Revista de neurología, Neurocirugía y Psiquiatría, 39(1), 46-51.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2014). Tell it again! the Storytelling Handbook for Primary English Language Teachers. British Council.

Espada, M.C. y Grau, C. (2012). Estrategias de afrontamiento en padres de niños con cáncer. Psicooncología, 9(1), 25-40.

Fabbro, F., & Cargnelutti, E. (2018). Neuroscienze del bilinguismo: il farsi e disfarsi delle lingue. Astrolabio.

Freddi, G. (1990). Azione, gioco, lingua: fondamenti di una glottodidattica per bambini. Liviana.

Freddi, G. (1994). Glottodidattica: fondamenti, metodi e tecniche. UTET libreria.

Grau, C. y Espada, M.C. (2012). Percepciones de los padres de niños enfermos de cáncer sobre los cambios en las relaciones familiares. Psicooncología, 9(1), 125-136.

Grau, C. (2013). Fomentar la resiliencia en las familias con enfermedades crónicas pediátricas. Revista Española de Discapacidad. 1(1), 195-212.

Kanizsa, S. y Luciano, E. (2009). La scuola in ospedale. Carocci.

Krashen, S. D., & Terrell, T. D. (1983). The natural approach: language acquisition in the classroom. Pergamon Press.

Lizasoain, O. (Septiembre 2021). De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de pedagogía hospitalaria. EDUTEC. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, (77), 5-16.

March, J.C. (2017). Humanizar la sanidad para mejorar la calidad de sus servicios. Revista de calidad asistencial, Vol 32 (5).

Martinez Soto, A., Bautista Girona A. B. (2013). Vivir aprendiendo. Protocolo de actuación para alumnos con cáncer. Asociación de Familias de Niños con Cáncer de Castilla-La Mancha (AFANION).

Masoni, L. (2016). Inglese lingua utile: language users nella scuola dell’infanzia, in Infanzia, (6), 385–388.

Modenini, M. & Rivoltella, P. C. (eds). (2012). La lavagna sul comodino: scuola in ospedale e istruzione domiciliare nel sistema lombardo. V&P.

Molina, M.C. (2020). Pedagogía hospitalaria. Claves teóricas y enfoques para la práctica. Octaedro.

Organización Mundial de la Salud. (1946, 19-22 de junio). Preámbulo de la Constitución de la Asamblea Mundial de la Salud [sesión de conferencia]. Conferencia Sanitaria Internacional, Nueva York, Estados Unidos.

Schwartzmann, L. (2003). Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: aspectos conceptuales. Ciencia y enfermería IX (2), 9 -21.

Schumann, J. H. (1994). Where is cognition? Emotion and cognition in second language acquisition, in Studies in Second Language Acquisition, (16), 231–242.

Terris, M. (1980). Tres sistemas mundiales de atención médica. Cuadernos médico Sociales, 14, 27-35.

Tullet, H. (2014). Mix it up!. Chronicle Books

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

How to Bring English as a Foreign Language to Hospitalized Primary School Students

Giorgia Fattori, ItalyStrategies for Assisting English Language Learners with Specific Learning Difficulties (SLDs) in the Writing Centre

Jimalee Sowell, US