Strategic Competence and Why We Don’t Love It As Much As We Should

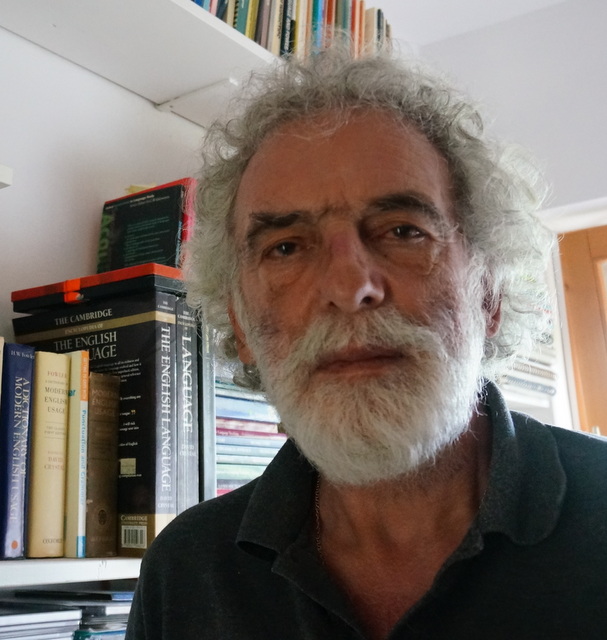

Steve Hirschhorn is a British language teacher and teacher trainer with 40 years of experience at all levels of the profession both in the private and public sectors. Although officially retired, Steve still travels delivering training, workshops and seminars for teachers and other professionals. His special interests include Silent Way, the use of the Cuisenaire Rods (for which he has written a book to be published in 2022) and generally challenging the current apparently irresistible trends in language education. He has a Master’s in Applied Linguistics, a Post Graduate Certificate in Higher Education (distinction) and is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. He has twice won the Walpole Prize for Excellence in Teaching. Email: hirschhs@zoho.com

I’m no expert on language testing. I dislike it and I dislike what it makes teachers and students do. From what I have seen it corrals both categories of participant into boxes and then applies a score (to the latter category) represented by a letter and perhaps a number or worse, a vague reference to being ‘intermediate’. These letters and numbers can then be used to explain what ‘level’ one is and whether or not one can do certain things – apply for a university place, a job, a further course of language and so on. But what has been tested? Grammar – for sure. Lexis – almost certainly. The ability to communicate? Not as far as I can see. But then, I’m no expert on language testing.

Consider this: “Please… I like for buy this thing what make stop raining. You have?” This, in the context (and all language must exist in context) of a shop selling coats, boots, waterproof items etc. and accompanied by appropriate gesture can leave no doubt in the mind of the shop keeper that the speaker wants an umbrella. But wait: the grammar is quite wrong, the lexis is almost non-existent. So how did this piece of communication achieve the success it so clearly has? Its success is due in part to context but it’s also due to the risk-taking of the speaker, and the use of strategic competence (SC).

SC can be defined as verbal and non-verbal activity that is used to support a communicative act which is missing some otherwise vital component - structure or lexis, for example. Its components can include paraphrasing, circumlocution, repetition, avoidance in the verbal camp and gesture, mime and ‘air-drawing’ in the non-verbal.

SC requires a good deal of courage on the part of the speaker, what we, in the business, call ‘risk-taking’. You could, after all, end up with metaphorical egg on your face if the interlocutor doesn’t or won’t understand you! I’m sure that as L2 learners, we have all engaged with SC in a variety of different ways. I recall trying 16 different pronunciations of ‘mayonnaise’ in a tiny Greek grocery shop to be met each time with the same negative tongue click and backward head movement. I also remember camping in Germany with my girlfriend (both of us 16) who needed sanitary products; now my German wasn’t up to that and she refused to go in to the chemist’s, so I was left with some words and sign language. I came out with water purifying tablets! But employing SC doesn’t presuppose a low level of competence, one might be at C1 or C2 (there, I’ve used those arbitrary letters and numbers) but still be missing a structure or item of lexis. What SC does do is increase the chances that a particular communication or speech act achieves success where without SC, it may not. And the icing on the cake is that the risk-taking involved offers a window onto students’ interlanguage development.

SC then is a massively important part of a learner’s directory of support mechanisms but do we prize it? Do we teach it? Do we foster it? Do we include it in our testing? The answer is generally in the negative, speaking from quite long experience. In fact, I would go further and say that teachers often don’t recognise that it’s occurring and may ‘correct’ an utterance which contains elements of SC. And this raises some interesting questions…

A learner is trying to express something and can’t do it without some aspects of SC use – what should a teacher do?

- Step in and ‘help’: thus denying the learners an opportunity to stretch and practice habits which will serve her well.

- Ignore completely: thus leaving the learner with no direct feedback on the acceptability or intelligibility of his utterance.

- Correct: thus training the learner not to risktake since it will result in intervention – however benign.

Or could we do better? Could we perhaps engage with the learner and ‘play the game’ using subliminal processes to offer support.

Let’s look at a couple of actual examples:

L: “Yes, I erm.. I stayed for the er bus, you know but it is very … it not coming. 8 o’clock … 8.30 o’clock I stay there so now I think I must to walk!”

T: “Ha! So you were waiting for the bus for a very long time”

L: “Yes, yes, I waiting…”

T: “Ok, and then you decided to walk?”

L: “Yes, I decide to walk”

T: “Wow! And it’s a very long way, a long walk isn’t it!”

L: “Yes, it was maybe 9.30 o’clock I arrive here”

T: “Ok, so you got here at 9.30? Half past nine?”

L: “Yes, yes, half past nine, I got here.”

Now this interchange seems to value the communicative act the learner is undertaking since the teacher is engaging as a human being rather than as a teacher. The teacher responses are designed to give additional information rather than directly correcting and all require some kind of response from the learner if only in agreement. Twice the teacher rephrases (grades) so that the learner can benefit from some extra, useful information. This kind of interaction does not magically fill the gaps in the learner’s store but what it does do is to encourage the learner to take a risk in the certain knowledge that she will be understood and supported.

Here’s another:

L: “I was lucky, you know, if I didn’t … if I didn’t saw her that day, maybe you know, we can’t, couldn‘t got married. What a disaster!”

T: “Wow! Yes, so I wonder what would have happened if you hadn’t seen her that day.”

L: “Yes, she would marry some other guy!”

T: “Right, she probably would’ve married someone else but you did see her and so you were able to get married!”

A slightly more complex interchange but the principles remain the same. The teacher tries to subliminally offer more information and the learner has access to some fairly tricky structure but at the same time is understood, supported and engaged.

If what I am saying seems to make sense, why is the focus of language testing so geared towards correctness in structure and lexis? Why are we not measuring the SC of learners – their ability to do what language is made for: communicate? In my very first example, the speaker went into a shop to buy an umbrella and presumably came out with that article! As such, the communicative act was as successful as it would have been had she gone in and said “Hello, I’m after a decent umbrella, it’s pouring down out there, do you have any nice ones?” And yet in a testing situation the former would be unacceptable and the latter would get full marks.

I’m arguing for several things but at the top of my list is that teachers foster SC, literally showing students what they can do to substitute an as yet unknown structure, get around an item of lexis not yet known, setting activities which specifically challenge students to use their SC to achieve communicative success. I’m also arguing that we should be including SC in our language testing. We should be acknowledging that even if an utterance is completely ‘wrong’ in conventional terms, if it achieves its aim, it must be valued and marked as such.

I’ll go a step further and suggest that a C1 students who produces a perfect 2nd conditional (excuse my anachronistic references here) certainly deserves acknowledgement that she has learned and perhaps automatised that tricky bit of language but an A2 student who manages to get the meaning of that structure across using unconventional means (SC) deserves at least as much appreciation, if not more.

But what do I know? I’m no expert on language testing.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Strategic Competence and Why We Don’t Love It As Much As We Should

Steve Hirschhorn, UKWhere Are We? Who Are We? Why…? Changing Realities

Susan Holden, Scotland, UKStaying Positive in Difficult Circumstances

Marjorie Rosenberg, AustriaTeaching in the New Normal – Challenges and New Opportunities

Mojca Ketiš, SloveniaSo What Do You Do Then?

Steve Hirschhorn, UK