Casting a Podcasting Spell: Legal English Podcasts International

Štěpánka Bilova, Radmila Doupovcová and Barbora Chovancová are teachers of English for Lawyers at Masaryk University Language Centre in Brno, Czech Republic. All three are involved in material design. They promote student autonomy and motivation and are also interested in innovation and creativity. Recently, together with other colleagues from the department, they have published a book of texts and accompanying activities entitled Právnická angličtina (Legal English) aimed at Czech lawyers, law students, translators and other professionals interested in the language of law. Emails: stepanka.bilova@law.muni.cz, radmila.doupovcova@law.muni.cz, barbora.chovancova@law.muni.cz

Introduction

When everything comes together and works as it should, what happens in the language classroom is a kind of magic. Students get so engrossed in their tasks that they learn without consciously noticing. But this magic does not always come naturally; it often requires effort. When planning for a mini project that would truly engage our students and make them work hard on their professional English, in our case Legal English, we decided to add an unusual and appealing task (creating podcasts), a little bit of technology (online recordings), work with peers (teams of students), and an international element (cooperation with a foreign university) in the hopes of sparking something magical.

What to expect

This article shows how the above-outlined plan was put into practice by teachers from Masaryk University and the University of Pécs who designed a project with the aim of incorporating an international element involving student-made podcasts into the existing fixed-syllabi Legal English courses at both institutions. The reader is given a step-by-step account of the project planning and implementation stages and, most importantly, insights into what worked well and what did not. The text does not aspire to be a technical, academic article but more of a practical manual helping other teachers planning similar projects to learn what worked well and what might be wiser to do differently.

Preparatory phase

The teachers from both institutions designated to take part in the project met several times online, first for introductory/fact-finding meetings and later for planning purposes. When thinking out the whole project, they had to plan carefully around several constraints, the most significant of which was the lack of overlap between the syllabi topics at the two Faculties of Law. The Legal English courses at each institution run for several terms and the areas of law covered in the concurrent sessions did not match at all. After much discussion, the decision was made to form single-nationality teams (Czech and Hungarian) rather than mixed ones. The students in each national team would pick a topic relating to what they are covering in class and create podcasts. It was a tough decision to make because the downside is obvious and significant, i.e., no real necessity to communicate in English when creating the podcasts. To counterbalance this problem, a requirement was made for the students to obtain information from their foreign counterparts and present the findings in their podcasts. They would thus still need to communicate in English on technical issues in their respective national legal systems and, equally important, to practice the linguistic skill of mediation when presenting the findings to their Podcast audiences.

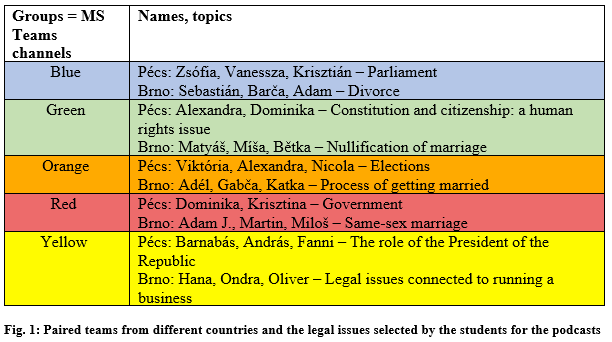

Phase 1: Topics + Teams

Students at both law faculties were put into teams of three and were asked to agree on a legal issue connected to a topic covered by their respective syllabi and to prepare a podcast on it. They were asked to incorporate both information they could research themselves (concerning the laws in their own countries and those from abroad) but also information that could only be obtained from the law students from the other country. The latter requirement was essential for the task, as it created an information gap and made the activity relevant and meaningful. The instructions thus explicitly said the information sought must not be ‘Googleable’, i.e., should concern inside information, first-hand experience, or personal views.

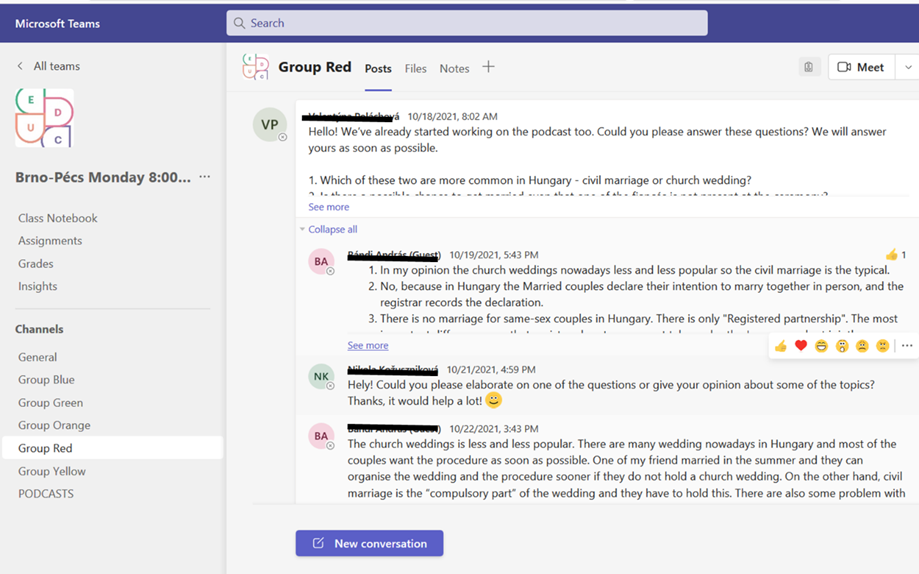

Each team from a given country was then assigned their counterpart from abroad and thus Czech–Hungarian working groups were created. MS Teams was used as the main communication platform for this cooperation. The working groups met together twice under their teachers’ supervision in shared sessions during their class time, and they also worked autonomously, exchanging information and completing tasks outside their lessons in any way they saw fit (e.g., in writing and/or in MS Teams meetings or via social media of their choice).

Preparation at home institutions

The initial interaction between the international working groups was carefully scaffolded by the teachers. Before the students met online, they were each asked to prepare a short professional/personal introduction of themselves and upload an “About me” post, together with their photo, into their MS Teams group channels. This proved to be a very good idea as having a few interesting facts about the other team members beforehand helped the students to break the ice and kept the initial conversation going.

|

My name is Václav. I’m 20 years old and currently in the second year of law school. I love sports and fitness. I’ve been playing volleyball since I was little and last year I started passing my experience onto younger players through coaching. When I’m not playing or training volleyball, I’m either in the gym or doing some other sports. I also love travelling with my friends and family. So far the most interesting class for me was the Roman Law. Despite my deepest hatred towards history I find the genius of ancient Romans somewhat exciting and learning how their principles survived to this day is very intriguing to me. |

Fig. 2: A sample of an “About me” post

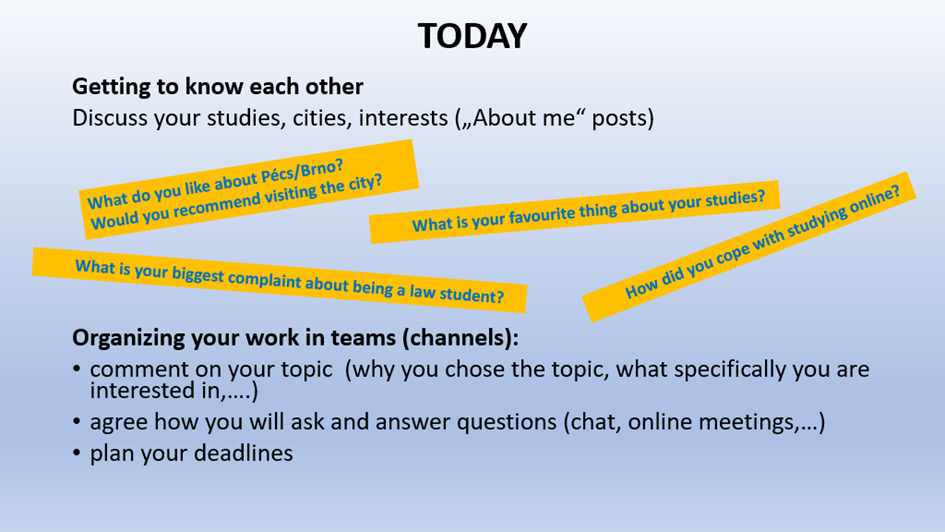

Kick-off meeting in MS Teams + meeting international partners in the MS Teams channels

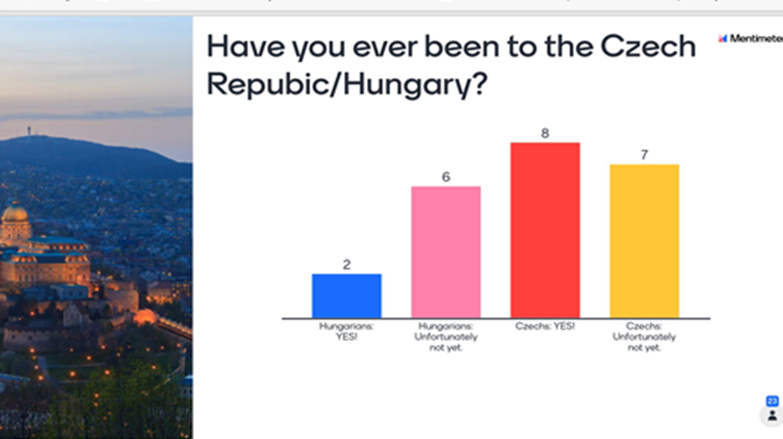

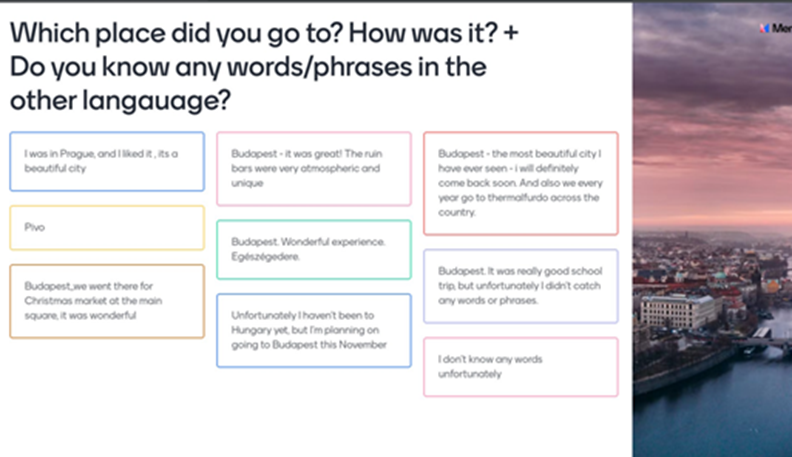

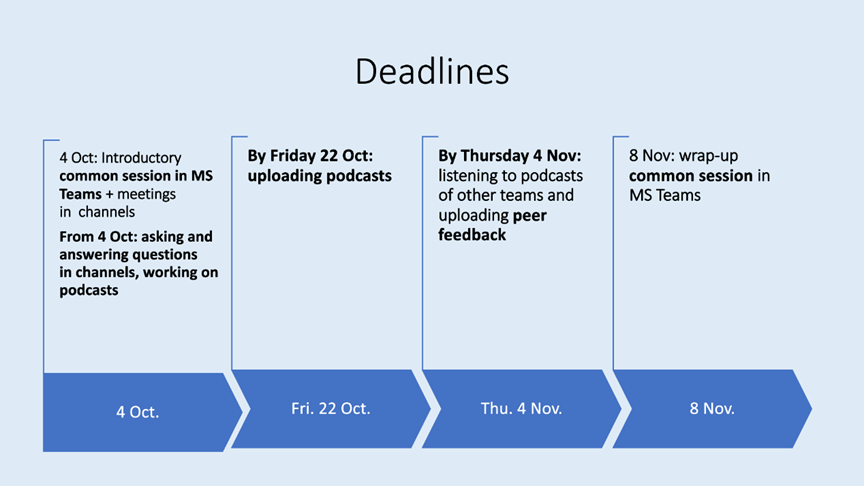

The first direct contact between the participants happened in what we chose to call a kick-off meeting. It took place in a shared lesson led together by a Czech and a Hungarian teacher. An icebreaker focusing on students’ experiences with the other culture (Czech/Hungarian) was conducted with the whole class (see Fig. 3). Students were then provided with more details about the project, its aims, description of tasks, and deadlines (see Fig 4). This clarity of instruction was believed to be essential for the success of the undertaking.

The second part of the kick-off meeting was reserved for individual interaction of the working groups. The paired Czech/Hungarian teams were assigned a pre-prepared channel in MS Teams. They were given time first to get to know each other and after that to plan their cooperation and strategy for obtaining the information needed for their respective podcasts. The team members introduced the legal issues/topics they had chosen, explained what would be needed from their counterparts, and agreed on how they would exchange information. Last but not least, they were asked to agree on their own internal deadlines.

Phase 2: Producing the podcast

Gathering and exchanging information – asking questions

Since one of the aims of the project was to promote learner autonomy, it was left to the groups of Czech and Hungarian students to decide how they would interview their colleagues. Most of them used the space provided in MS Teams for online meetings and chat exchanges or for online documents where they asked and answered their questions, but some teams used alternative platforms like Facebook or Messenger.

|

Questions by Hungarian students Hello! Answers by Czech students Valentýna: 1. Personally, I've been talking about politics a lot. I'd say that these days it's a general topic of conversation between people. Because elections took part (sic) in our country 2 weeks ago and brought us surprising results.

Nikola: 1. For me I can say, that I talk about politics often as well. I feel like in our country there is always something going on in that area that you can never run out of things to talk about. For example right now the most discussed topic is our president's illness.... 2. I think we (specifically at our school) live in a big bubble, where we think a lot of young people are interested in politics but I personally think it is not the case. I think mostly young people who are at universities think about politics and vote. We just had the elections to the Czech Parliament and I was sitting at one of the places where people from Brno could go vote and the percentage of young people that came in that specific area was not more than 20% I would say. So I think there's this misconception, since we study law and deal with politics a lot I'd say, that a lot of young people vote but I think the reality is really different. |

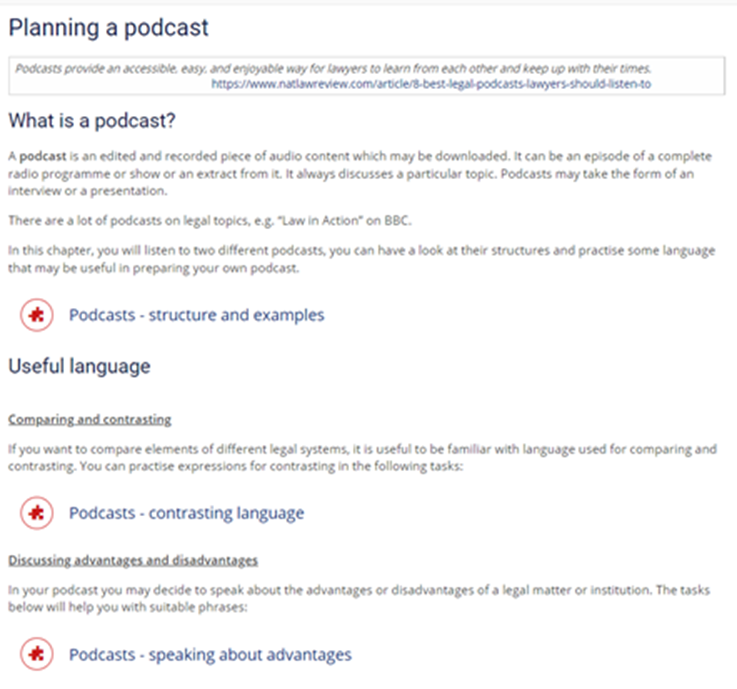

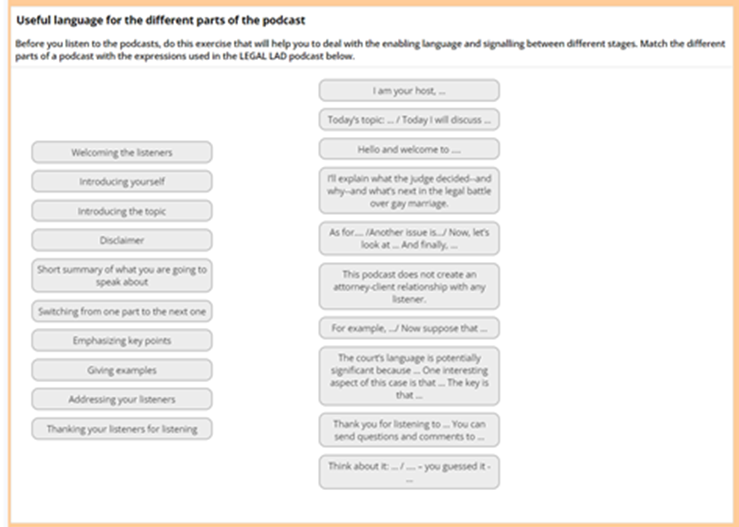

Creating podcasts – preparation

How does one go about creating a podcast? Adequate preparation and careful scaffolding are crucial to foster student success in any endeavour, and podcast creation is no exception. The teachers therefore designed e-learning support consisting of activities on podcast structure, examples, tips for a good podcast, and useful language (e.g., for speaking about legislation, mediating information, signalling, comparing and contrasting).

The students were shown a format used by professional podcasters illustrated by model examples from the area of law (e.g., https://www.quickanddirtytips.com/ and https://studylegalenglish.com/). They were encouraged to make a professional sounding podcast including a jingle, disclaimer, and other features, though these were not obligatory. As for the technical side, the teams were free to use any platform or software.

Creating podcasts – the task and preferred formats

Students were given the following instructions: prepare and record a podcast of 10–15 minutes comparing and contrasting the Czech and Hungarian legal systems in relation to a specific legal issue. Include information you have obtained from your colleagues from the other country. All team members must be equally involved.

As each podcast was created by a team of three members, the students had to decide on the format, either as a series of monologues or as a more interactive form such as a discussion or interview (a more detailed explanation of formats was provided through e.g. https://rachelcorbett.com.au/blog/podcast-types/). The most popular choice of format was a series of monologues by three consecutive speakers. The reason seems obvious—it is simple to prepare. The students shared the knowledge they had gained through the interviews of their colleagues from the other country and by researching the details of the topic. Those podcasts in interview or discussion format, which some teams selected, were much more dynamic and as a result more attractive for listeners. Students often assigned roles to each member of the group, and we witnessed the following combinations of speaker interactions:

- a single host and two guest speakers, e.g. an expert on Hungarian law and an expert on Czech law;

- two hosts (one host and a co-host) and an expert in the field, e.g. a constitutional judge from the Czech Republic;

- conversational and co-hosted podcasts in which all speakers explored their topic by asking and answering questions and sharing their opinions and experience.

Comparing the results

The results were impressive. All the podcasts students created demonstrated an incredible level of sophistication, insight into the topics, professionalism and respect, appreciation of different opinions on controversial issues, but often also wit and understanding of the genre.

It was also interesting to observe the differences in style between the podcasts produced by Czech and Hungarian students, even though it is hard to establish what was the cause—be it cross-cultural differences, different expectations concerning course work, or simply coincidence.

It is possible to generalise that the Czech students allowed themselves to fully explore the boundaries of the genre, aiming for infotainment, rather than just presenting the facts. There was often banter between the presenters, some of it improvised in places. They also used the full range of podcast formats.

The Hungarian students, on the other hand, tended toward a more serious approach. Their podcasts were more technical and scripted and typically focused on the content rather than on the overall appeal and entertainment aspects. The legal information they offered tended to be more in-depth, presented in formal legalese rather than mediated for the benefit of the general audience. They also followed the instructions more closely, using the suggested phrases and echoing the e-learning examples. Their preferred format was the monologue, in which the three individual speakers presented one by one.

Phase 3: Peer feedback

After all the teams had published their podcasts on an MS Teams podcast channel, the students were asked to listen individually to three podcasts produced by other groups (one Czech, one Hungarian, and one of their own choice) and subsequently to provide feedback on them. To ensure that every podcast would receive feedback, it was compulsory for the students to listen to the podcast of the paired foreign team from their MS Teams channel.

Peer feedback was considered a very important element of the whole experience. Students were therefore given detailed instructions and sufficient support for providing it. A series of e-learning tasks focusing on the respective language, strategies, tips and examples were designed for them. An activity worth mentioning here was one that trained students to use meaningful adjectives to express their opinions on the reviewed podcasts. In class, we explained that the phrase “your podcast was interesting” was forbidden, due to the dual meaning of the phrase and the general vagueness that it conveys. Students were asked to brainstorm as many synonyms of “interesting” as possible. Involving all students using the interactive tool Mentimeter made the activity even more… captivating, amusing, engaging, gripping.

|

Comment on the:

Write down at least 70 words in your feedback. Do not use the word “interesting” in your comment. |

Fig. 10: Instructions for peer feedback

|

Nikola: Okay where do I start? I very much enjoyed basically the whole thing. The beginning was great, all of you sounded super enthusiastic and I really liked the whole structure of your conversation. It was easy to follow you all along and the transitions between your speeches were smooth so it really seemed like a real interview. Even though I thought I already knew about this topic enough you surprised me with even more new information. Overall your English sounded really nice so it was pleasant to listen to you the whole time. I think you should start recording podcasts for real, you were such great actors.

Gabriel: You had a great energy and you charge your listeners, I enjoyed listening to you. And the sound effects? I loved it! There were a few slips of the tongue but that is a part of it, nobody’s perfect 😊 You followed up each other nicely, the concept of the conversation was well-structured and pleasant to listen to and the topic was understandable. I liked you mentioned also children, surnames and money. The technical side was shipshape, I have no objections 😊

Vanessza: I really liked the fact that each of you had a role and there was an interviewer and legal counsel from both the Hungarian and Czech sides because it made the podcast even more dynamic. You’ve used the information we gave you very well. The conversation is well structured, contains a lot of useful information and the language is understandable. It was a good idea to take a “break” between the different parts—so people can’t lose concentration. In conclusion, this is a very informative and enjoyable podcast, you have solved this task very well. Thanks for this cooperation! 😊 |

Fig. 12: Unedited samples of peer feedback

Phase 4: Wrap-up session

The final step of the student cooperation was a wrap-up session in MS Teams. In the first part teachers summarized the activities and commented on the students’ achievements in all areas, namely:

- Communication: meeting new people, agreeing on deadlines/task management, asking questions, answering questions.

- Creating podcasts: podcast planning, dividing the labour, doing research, scripting, disclaimer forming, summarizing information, recording + revising, overcoming technical problems and other obstacles, posting the final product (requires LOTs of courage).

- Giving feedback: choosing appropriate language, being diplomatic and considerate.

- Professional knowledge building: learning about various branches of law, expanding technical vocabulary.

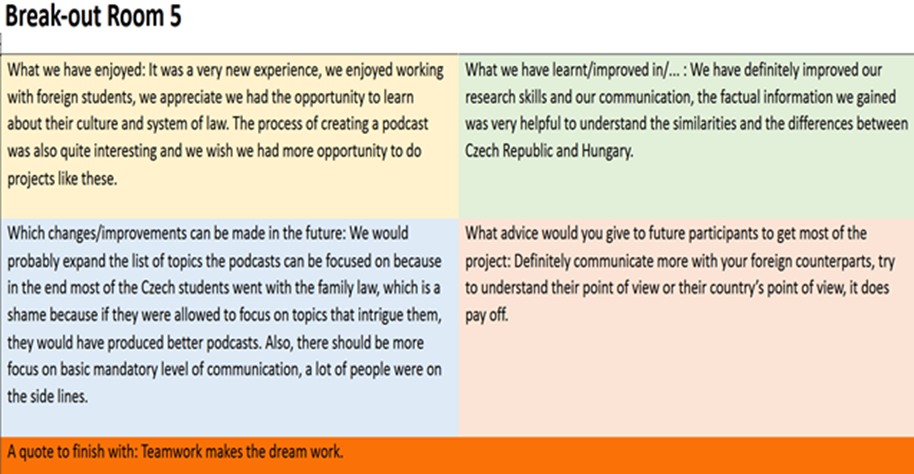

In the second part of the wrap-up session, students provided their feedback in breakout rooms. They filled in a shared document commenting on what they had enjoyed, what they had learnt and in what areas they had improved, and what changes and advice they would suggest for future projects. They were also asked to choose a quote to finish with. You can see a sample of one group’s work below (Fig. 13). Below we summarize the comments the participants made.

Students enjoyed that the whole experience was something new and fresh. Some found the process of creating and recording a podcast “worthful and amazing”, ad many said it was truly enjoyable. Others observed the tasks had been challenging but attractive. Students were happy that they made new friends and cooperated with lawyers-to-be from abroad, and they appreciated the opportunity to get to know another culture and its legal system. They liked that they expanded their knowledge of the law and the other country, had to communicate in English, and had a lot of writing and speaking practice.

Many groups stated that they had improved their communication and research skills, and some mentioned they had become more fluent in speaking. On the other hand, some students found it difficult to communicate freely online, to keep the conversation going, take turns, and find topics for small talk. Some said it was tricky to coax some shy or unwilling participants into talking. The groups also mentioned that they practised their legal English and extended their technical vocabulary.

The ideas for future changes included mainly having more time to complete the tasks and more joint sessions. Also, some students called for more supervision by the teachers, namely intervening in groupwork when the cooperation was failing and being more specific about the podcast content. Some suggestions were not feasible, such as visiting the other country to meet in person or being provided with professional technical equipment for creating podcasts.

The advice given to future participants concerned both intercultural communication and the process of creating podcasts. They suggested finding more time for casual conversation (getting to know each other) and at the same time starting early with the work. Many groups offered practical tips focused on housekeeping, such as setting and keeping deadlines, choosing an attractive topic for the podcast, finding relevant information, and rehearsing the podcast before recording it. The key advice was: “don’t leave everything to the last minute”, “think about how you present the information, not just what you say”, and “don’t take it too seriously, enjoy”.

Final thoughts

To summarise and to reflect, we decided to follow the same feedback format our students were asked to complete. It is interesting… sorry, inspirational to put oneself into one’s students’ shoes from time to time.

We have enjoyed having a chance to work and connect with colleagues from abroad. Working with the Hungarian teachers was a treat, and it was nice to share the workload and double the brainstorming potential. Owing to this project, we have learnt more about our own students (e.g., unexpected hobbies, like them being tap dancing pros, playing in a Metal band or reading Dostoyevsky and Kafka) and made stronger bonds with them.

We have improved our international project drafting and implementation skills, cross-border classroom management, and ability to think on our feet and outside the box.

Next time, we would change or, more precisely, expand the training support for the students when dealing with online communication as such, e.g. awkward silences, too long utterances of a colleague, managing a partner who is too pushy, and the like. We have felt that more emphasis should be placed on scaffolding the speaking element by the teachers beforehand.

Our advice would be to focus on trying to strike the right balance between student autonomy and checking the progress of the group’s work but not hesitating to step in early in case of communication difficulties while handling the teamwork.

As often happens when doing something for the first time, there was a learning curve both for the teachers who designed the whole project and for the students who took part in it. All in all, we have found the experience truly rewarding. It was so delightful to listen to the final podcasts. The students were smart, open-minded, relaxed and funny, and fully engaged in the activity, and it left us with the wonderful feeling that all the hard work paid off, on the part of both the students and the teachers. And that was, believe us, magical.

This project was made possible by the support provided by an EDUC project (https://educalliance.eu/).

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

Escape Game as a Revision Tool

Katka Chudová, the Czech RepublicCasting a Podcasting Spell: Legal English Podcasts International

Štepánka Bilová, the Czech Republic;Radmila Doupovcová, the Czech Republic;Barbora Chovancová, the Czech RepublicFrom Genes to Memes: Meme-based Activities in the ESP Classroom

Markéta Dudová, the Czech Republic