From Genes to Memes: Meme-based Activities in the ESP Classroom

Markéta Dudová studied at the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Czech Republic. She holds a PhD in Literatures in English, specializing in English Romanticism. She currently works at the Masaryk University Language Centre where she teaches English for Specific Purposes (ESP) at the Faculty of Science. In her research, she is interested in the use of literature in ESP courses, metaphorical thinking and visual learning.

Introduction

Memes have become an everyday part of our online experience. Memes have a prominent position in the communication of our students, who, as digital natives, are permanently surrounded by visual images. Today, images dominate the conceptual world of the young generation, a generation which “thinks in pictures and communicates through pictures” (Wasilewska 2017, p. 43). Timothy Gangwer, one of the first advocates of visual teaching, describes today’s students as “by far the most visually stimulated generation that [the educational] system has ever had to teach” (2009, p. 1). To keep up with the increasingly visual world, language lessons should therefore approach images not just as a teaching aid or decoration but as a crucial communication means through which ideas and discussion can be encouraged (Donaghy & Xerri 2017, p. 3).

Memes, besides having a strong visual component, can also serve as an unexpected source of inspiration for the ever-despairing language teacher, always on the lookout for new activities. Some memes have great potential which can be harnessed by using them as a template for speaking activities, as memes seem to resonate with today’s students by triggering their emotions and stimulating conversation. Memes can be used in a language lesson “as a short warm-up or a filler” (Wasilewska 2017, p. 48) “to promote speaking with the ultimate goal to facilitate the acquisition of all the linguistic skills, productive and receptive” (Romero & Bobkina 2017, p. 60). Memes can also create a full-fledged lesson to make the most of their visual appeal to students. Despite the visually rich world we live in, our ability to understand images and communicate through them should not be taken for granted: the skill of visual literacy needs to be systematically fostered as image interpretation involves a broad set of skills ranging from simple identification “to complex interpretation at contextual, metaphoric, and philosophical levels” (Yenawine 1997 quoted by Romero & Bobkina 2017, p. 61). Further, memes are effective as enjoyable tools to develop these skills.

Theoretical background

The metaphoric dimension of images was one of the reasons why I decided to introduce memes into my English lessons. I use memes and meme-based activities in English for Life Science, which is a course for master’s students of various biological disciplines. The primary motivation to incorporate memes into the course was to gently draw students’ attention to the role metaphor plays in science. Though it is commonly thought that science and metaphor “mix about as well as oil and water” (Gibbs 1999, p. 169), a closer look at scientific language provides good evidence of the ubiquitous presence of metaphors in scientific disciplines, whether in the form of models (as in the plum pudding model of the atom) or in scientific terminology (for example, the term black hole). Generally, metaphors tend to be underestimated by scientists. Advocates of a more creative approach in science, nonetheless, stress the role of metaphors in giving rise to new ideas: “Metaphoric perception is, indeed, fundamental to all science and involves bringing together previously incompatible ideas in radically new ways” (Bohm & Peat 2000, p. 23). Metaphorical thinking thus should have a firm place in the training of future scientists as it can contribute to the development of visual literacy as well as promote scientific creativity.

The term meme itself is a metaphor. It was coined as an analogy to gene to express the idea of a piece of cultural information (e.g., religion) that “passes along from person to person” (Marwick 2013, p. 12). My meme lesson is preceded by a lesson on genetics and, due to its light-hearted character, it serves the role of a welcome break from highly specialized content. The biology students I teach are not usually aware of the original conceptual link between genes and memes—young as they are, they are familiar with the now popular format of a meme as an internet joke. Consequently, they are amazed to see that the popular social media phenomenon that has become a staple of our everyday communication in fact originated in their own discipline. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins introduced the concept in his 1976 bestseller The Selfish Gene in his attempt to explain the spread of cultural information on the model of biological evolution. According to Dawkins, memes, i.e. the cultural equivalents of genes, replicate by leaping from brain to brain via the process of imitation. In the late 1990s, Dawkins’ term was taken up by the internet culture to describe internet trends and jokes (Marwick 2013, p. 12), an event which even more fortified the connection between genes and metaphor (Marwick 2013, p. 13).

Practical examples

Although the following meme-based activities were used in English for Life Science, the activities can be modified and adopted in any ESP or GE course. The meme lesson starts by the students working in pairs, describing to each other the last meme they saw or the last meme they can remember. Students usually pull out their mobile phones to show the memes to their partners, putting them into context. This warm-up activity usually generates a lot of laughter and ensures a good start to the next part of the lesson.

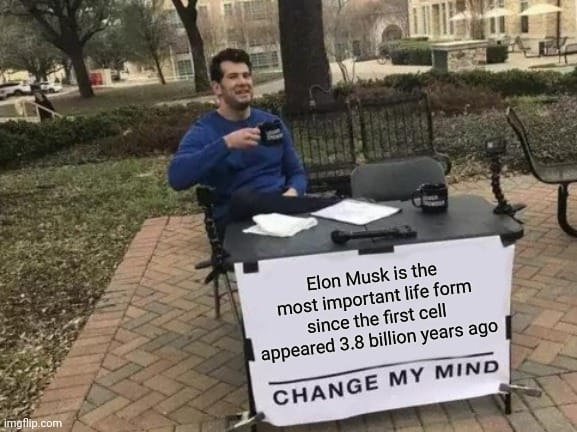

When students finish sharing their memes, I draw their attention to one particular meme to be used as a prompt for the next speaking activity. The meme depicts a man sitting behind a table. In front of the table, there is a statement expressing his opinion on a particular problem. The man is waiting for passers-by to come to talk to him, encouraging them with the “CHANGE MY MIND” sign written underneath his statement. The origins of the meme lie in a statement of a conservative podcaster and his view on male privilege but ever since its first appearance in 2018 (Steven Crowder’s “Change my mind” Campus sign), the meme has lived its own life—a typical feature of meme culture, which reacts to embarrassing behaviour, exposing it to ridicule in an incessant influx of new variants to parody the original one.

The statement up for discussion keeps changing in every new version of the “Change my mind” meme. The version of the meme I use in my lesson reads as follows: “Elon Musk is the most important life form since the first cell appeared 3.8 billion years ago / CHANGE MY MIND” (Fig. 1). The students are then asked to work in pairs: one student is going to defend the statement from the meme, giving reasonable arguments to support it, while the second student must come up with strong arguments to change their opponent’s mind. Students talk for about three minutes, in which they try to convince their opponent.

When the discussion is over, I ask half of the students to leave the classroom for about three minutes. In the meantime, the students in the classroom are going to create their own “Change my mind” meme on a sheet of paper with a marker. I ask the students to come up with statements related to biology or to science in general. The statement does not have to be controversial, though the nature of the meme deliberately calls for thought-provoking topics. I always have my own meme ready, borrowed from a statement made by Prince William, to give the students the idea: “Saving Earth should come before space tourism / CHANGE MY MIND.” Once the students are ready with their own statements, I invite the other half of the students back to the classroom, and they are welcomed by a sea of hands holding various signs. The entering students are asked to join the student whose statement is the closest to their interest and they try to change their partner’s mind. Their discussions take 3-5 minutes and in most cases the students speak enthusiastically about the topics.

When the discussion is over, I ask the students to take a quiz through which the parallel between memes and genes is revealed. The quiz has five questions such as:

1. A meme is

- the smallest unit of information capable of replication

- the basic unit of heredity which is transferred from parent to offspring

- an idea that is spread through social media

2. The term meme was coined by a

- sociologist

- marketing expert

- biologist

For some questions, there is more than one correct answer, and the quiz is made with the purpose of biology students realizing the conceptual connection between genes and memes. The quiz is followed by a discussion: Is the analogy between genes and memes helpful? In what sense are memes like genes? In what sense are they not? The students discuss these questions in pairs or small groups and then we go through their answers and opinions together.

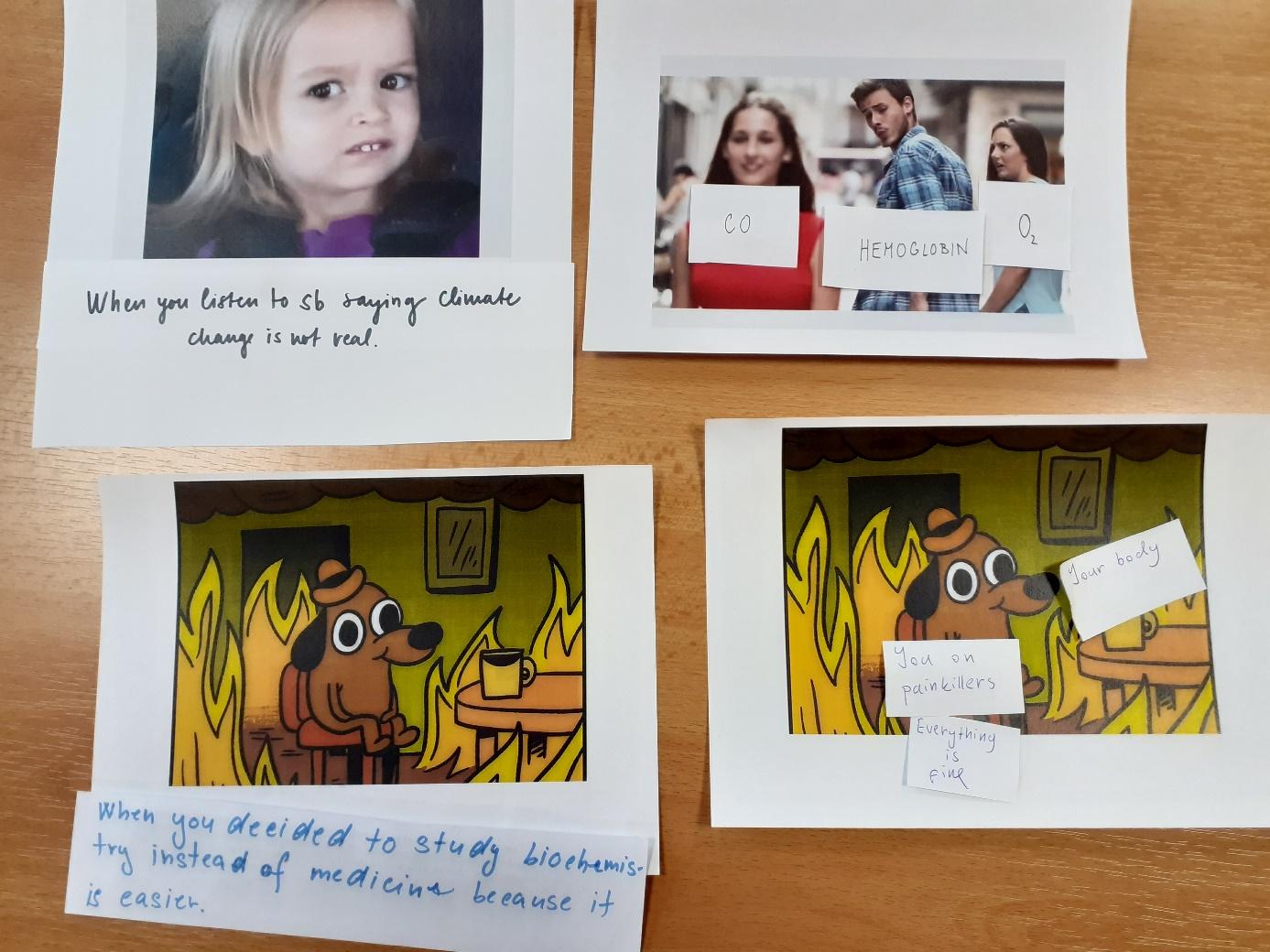

After the discussion, the lesson moves into its final stage in which the students are asked to create their own memes, thus moving from meme consumption and interpretation to independent production. There are various user-friendly meme generators (e.g., www.canva.com) that can be easily used in the class. In my lesson, however, the students are asked to create memes without the use of technology, which is quicker and more accessible for classrooms with slow internet connection. For the purposes of the activity, the students are divided into pairs or groups of three. Each group is given a set of popular memes which the students recreate by changing the caption. The caption should be science-specific in order to stick to the field of study of the course participants. When the students finish, the new memes are displayed on a desk for everyone to see and enjoy (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Even though there is no technology involved in the creation of the memes, the students’ final products still adhere to the definition of memes as the students’ collaboration brings up crucial aspects of internet meme culture, i.e. those of sociability, variability and participation (Marwick 2013, p. 13). The students are usually highly engaged in creating their own memes, laughing and talking vivaciously, and thus the activity fully harnesses “the participatory potential” of memes (Marwick 2013, p. 13). Online or offline, memes connect people together through a social, affective bond that creates an ideal environment for collaboration and creativity.

Conclusion

For students living in an increasingly visual world, in combining image and text memes offer practical tools for activating students’ creativity and speaking skills. The incorporation of memes into language classrooms, together with the need to process both words and pictures, helps to develop students’ visual literacy, enabling them to move fluently between text and images (Romero & Bobkina 2017, p. 61). Besides bringing a strong visual element into traditional classroom activities, memes are also perceived by the young generation of digital natives as authentic materials and as such they naturally stimulate their emotions, imagination, and conversation. Thus, the lessons into which memes were incorporated were characterized by smooth collaboration among students, lively conversations, and active engagement.

References

Bohm, D. & Peat, F. D. (2000). Science, order and creativity. New York: Routledge.

Donaghy, K & Xerri, D. (2017). The image in ELT: An introduction. In K. Donaghy & D. Xerri (Eds.), The image in English language teaching. Floriana: ELT Council.

Gangwer, T. (2009). Visual impact, visual teaching: using images to strengthen learning. New York: Corwin Press.

Gibbs, R. W. (1999). The poetics of mind: Figurative thought, language and understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marwick, A. (2013). Memes. Contexts 12(4), 12-13.

Romero, E. D. & Bobkina, J. (2017). Teaching visual literacy through memes in the language classroom. In K. Donaghy & D. Xerri (Eds.), The image in English language teaching. Floriana: ELT Council.

Steven Crowder’s “Change my mind” Campus sign. Know your meme.

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/steven-crowders-change-my-mind-campus-sign

Wasilewska, M. (2017). The power of image-nation: how to teach a visual generation. In K. Donaghy & D. Xerri (Eds.), The image in English language teaching. Floriana: ELT Council.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website

Escape Game as a Revision Tool

Katka Chudová, the Czech RepublicCasting a Podcasting Spell: Legal English Podcasts International

Štepánka Bilová, the Czech Republic;Radmila Doupovcová, the Czech Republic;Barbora Chovancová, the Czech RepublicFrom Genes to Memes: Meme-based Activities in the ESP Classroom

Markéta Dudová, the Czech Republic