- Home

- Various Articles - General

- British Council-St Giles Educational Trust: Classrooms in Action and Mentors in Action, Cuba

British Council-St Giles Educational Trust: Classrooms in Action and Mentors in Action, Cuba

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-38467299

Mike Williams is Head of Teacher Training at St Giles International Brighton and he leads on the design of global teacher training projects for St Giles’ linked charity, the St Giles Educational Trust (SGET): https://www.stgiles-international.com/about/st-giles-educational-trust

Mike’s English teaching career in ELT commenced in 1978: he held teaching posts in Egypt, Spain, Portugal, Brazil and the US as well as the UK. He has been a teacher trainer for 30 years, having delivered courses for teachers and teacher educators in a wide range of countries. Mike is a Cambridge CELTA and Delta tutor and an ICELT and CELTA assessor for Cambridge. He is also a Chief Moderator for the Cambridge ICELT.

Introduction

English language has always had a place within the Cuban curriculum. However, the continued growth of the country’s tourist industry as well as Cuba’s increasingly international focus during recent years has resulted in a greater emphasis on this within the government’s education policy. For 21st century Cubans, English is a key life skill.

A number of pioneering educationalists have striven for many years to ensure high quality pedagogy and resources. There is now an even stronger focus on the way in which English is taught in Cuba and in which teachers are prepared to embark upon their careers. 2019 saw the launch of a new English language curriculum.

There are two Ministries of Education in Cuba: the Ministerio de Educación (MINED) and the Ministerio de Educación Superior (MES). Their responsibilities include the implementation of policy and the national curriculum, commissioning or undertaking research, student assessment, materials design and Didactics (Methodology in ELT). They are outward-looking in their approach and they regularly invite external contributions to conferences from organisations from all parts of the world. In broad terms within the sphere of ELT, the former is responsible for the teaching/learning of English in secondary schools and the latter at university level, as well as teacher training.

Undergraduate trainee teachers of English aiming to work in the secondary or tertiary sector currently undertake a five-year programme of university training during which time (in addition to their pedagogical studies) they need to develop their own level of English proficiency to at least B2 level (CEFR). Their undergraduate degree programme has a strong theoretical element and it also includes teaching practice and action research. After graduation, some teachers work in secondary schools whilst others remain at their university, helping to raise the level of English of future graduates and taking responsibility for some key areas of input on theory. Working alongside all of these undergraduate and newly qualified teachers are the university tutors who oversee their initial and continued training and development.

In 2017, the British Council Cuba met with the representatives from the two Ministries of Education to share information about new approaches and strategies within English language teaching. The Ministries were interested in finding out more about the approaches used in the UK and whether aspects of these might be adapted for use in the Cuban context. The British Council has experience of supporting this process in more than 100 countries across the world. In order to help the Ministries to achieve their goals, it was decided that the collaboration agreements between the Council and the Ministries would include the organisation of some related professional development for teachers in secondary and tertiary sectors.

The St Giles Educational Trust (SGET) worked with the British Council to design and deliver this professional development. The SGET, which is linked to St Giles International language school, specialises in supporting teacher education and training in a number of countries in different parts of the world and it has substantial experience of working with partner organisations in Latin America.

The initial objectives for a ‘pilot’ course were:

- To align the teaching of listening and speaking skills in Cuba with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR)

- To consider different approaches to teaching these skills

- To explore other elements of communicative teaching

This investigation was firmly rooted in the Cuban context and it built upon the existing pedagogical knowledge base in Cuba.

The St Giles Educational Trust worked with the key stakeholders and the British Council Cuba to design a pilot course for under-graduate trainee teachers of English studying at Universidad de Ciencias Pedagógicas in Havana. Based on the success of the pilot, the Ministries and the British Council (working with the SGET) decided to expand the programme to other parts of Cuba: this became ‘Classrooms in Action’. The name of the project embodies its primary focus on practical teaching and training skills.

With additional support from the British Embassy, the project has since grown to include different groups of participants across Cuba: these range from undergraduate teachers to university professors with up to forty years’ experience in the field of English language and teacher education. However, the practical focus has very much remained at its heart.

The aim of this article is to share the SGET’s experience of the project so far.

Classrooms in Action

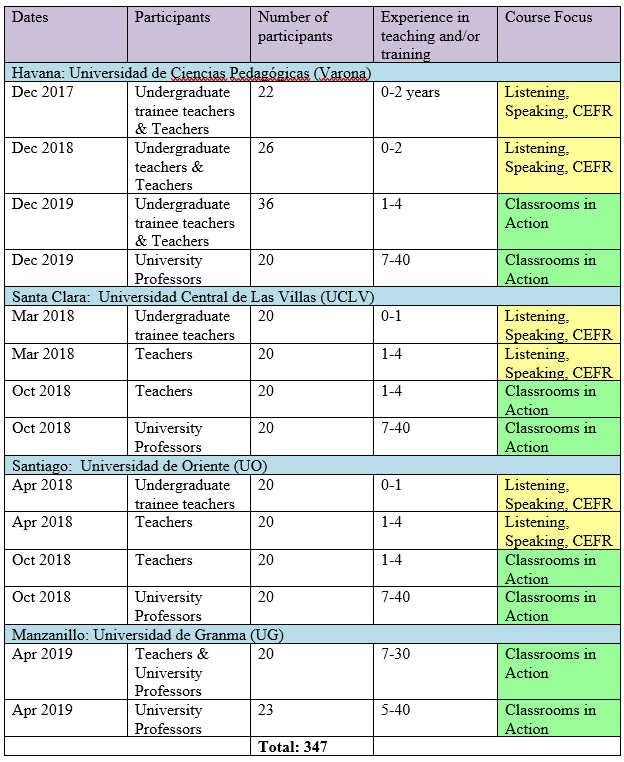

In order to implement the project, MINED, MES and the British Council Cuba enlisted the support of key universities across the country:

- Havana: Universidad de Ciencias Pedagógicas (often referred to as Varona)

- Santa Clara: Universidad Central de Las Villas (UCLV)

- Santiago: Universidad de Oriente (UO)

- Manzanillo: Universidad de Granma (UG)

Clockwise from top left: Santa Clara - Universidad Central de Las Villas (Mar 2018), Santiago - Universidad de Oriente (Oct 2018), Manzanillo - Universidad de Granma (Apr 2019), Havana - Universidad de Ciencias Pedagógicas (Dec 2019)

The involvement of the universities has been crucial: they have convened the groups of participants who have been selected by the Ministries, provided logistical support for the SGET teacher trainers coming to Cuba and made practical arrangements to enable these trainers to observe actual lessons in either secondary schools or at universities. Along with the Ministries, they have also ‘cascaded’ the outcomes of the project via the conference events which are part of the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) infrastructure for teachers and teacher educators across Cuba.

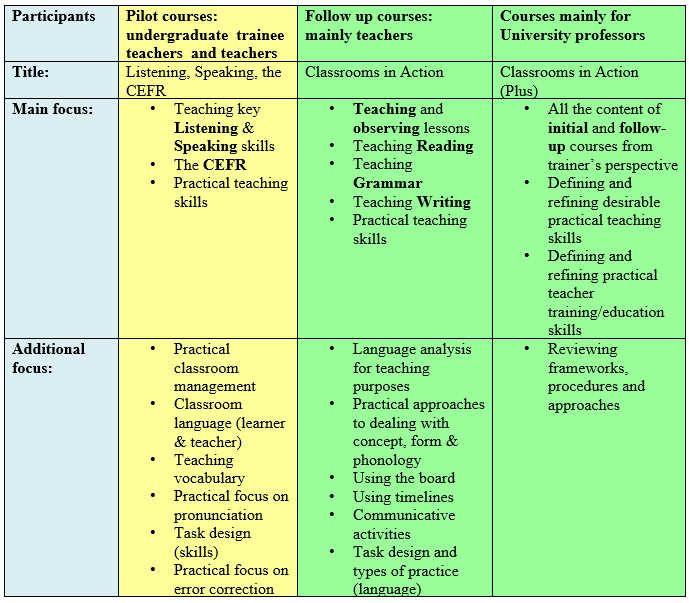

Table 1 below provides a summary of the way in which the project developed from the pilot phase into the various stages of Classrooms in Action.

Each course was given a main focus in order to guide its design and to ensure that it would meet identified needs. Inevitably however, a number of additional areas of focus emerged mid-course and so a degree of flexibility was needed throughout.

Table 1

A note on terminology: From primary school onwards, all Cubans call all their teachers ‘profesor’. As this is a ‘false friend’ in English, I have used the following term for ease of reference

- ‘undergraduate trainee teachers’

- ‘teacher’ - teachers of English, either in a school or a university context.

- ‘university professors’ - the teacher trainers/teacher educators for former students of the university (who are either now working as teachers in schools or who remained working in a teaching role at the university)

Though the courses were mainly designed for specific groups (as above), some of the cohorts were a mixture of the three. It was common for participants to find themselves in a room with course-mates who were currently their own students or who were their revered ‘profesors’ from many years ago and who had since been involved in producing the curriculum, assessment tests or teaching materials for Cuban schools across the country. This mix of age, experience and perspective as well as the openness and willingness of participants to share and discuss all aspects of teaching was partly what has made the project so interesting and rewarding. Despite some punishing temperatures and humidity, the degree of engagement from participants was high and all the people with whom we worked were extremely welcoming and enthusiastic.

All the courses were observed either by representatives of MINED, MES, the British Council Cuba and/or senior management of the universities (sometimes up to four people at a time). This was important in order to ensure that the courses were meeting the stakeholders’ objectives and also for effective ‘cascading’. More often than not, however, the observers ended up becoming actively involved in the sessions!

Our preconception was that participants were very familiar with ELT theory: this proved to be true and so the need to clarify terminology or references to developments in ELT over the last century hardly ever arose. However, the interesting challenge (from the pilot stage onwards) was arriving at a shared understanding of the practical skills which are specific to effective teaching/training and the development of techniques to build these skills. In general, the approach we used within the programme was, ‘practice to theory’, i.e. experiential learning which is then summarised within a more theoretical framework. Feedback from the participants suggested that their previous experience had mostly been of the opposite approach: we have found this to be the case in a number of the countries and contexts in which the SGET has worked. In order to focus more specifically on the development of actual teaching and training techniques, we needed to shift the emphasis away from just an awareness of theory to actual ‘hands-on’ teaching. This involved a lot of activities such as demonstrating, analysing, practising, coaching, reflecting and refining . This shift in focus from theory to practical skills is reflected in the name Classrooms in Action.

In order to extend the training beyond the confines of the courses’ input sessions and to help us to measure the impact of the training, we decided it would be useful to observe some of the participants teaching their in their real-life work context (secondary school or university). Though this process was not always straightforward, MINED, MES, as well as the local schools and universities themselves, provided the logistical support to enable us to see some real teaching in progress.

Taking this essential ‘next step’ (even though it only provided a ‘snapshot’) was something of a sea change within the project and it was perhaps our own greatest moment of learning. Despite our existing awareness of the Cuban context, nothing can compensate for the experience of being a ‘fly on the wall’ in a classroom. Until that point our planning and delivery involved creating hypothetical teaching situations during input sessions. For the participants, this meant playing roles at certain points (e.g. as school-age learners, observer trainers, givers of feedback, input tutors, peer teachers). When we were allowed into actual classrooms to see and feel the authentic context of the teachers’ work first-hand, the whole project was brought into sharper focus. This enabled us to work much more effectively with the stakeholders to set clearer goals.

The way in which the project subsequently progressed is summarised in Table 2 below:

Table 2

Mentors in Action

In early 2019, the stakeholders in Cuba selected a number of of the strongest participants from the Classrooms in Action groups who they believed would benefit from a further training/CPD course in the UK. These candidates were mainly drawn from the groups of ‘teachers’. The rationale for this was that they had some concrete teaching experience whilst at the same time this experience was still at a formative stage. Investing in and nurturing the future generation of teachers is a priority within Cuba’s ELT policy and peer mentoring is seen as an important vehicle for this.

In August 2019, in partnership with the British Council and with support from the British Embassy, the St Giles Educational Trust ran a two-week course for a group of 14 teachers from different Cuban provinces at St Giles International’s Brighton centre. This was given the name ‘Mentors in Action’. The course built upon the areas which had been covered during the earlier stages of the overall programme and it aimed to enable the participants to experience a different teaching and learning context. The young teachers then returned to Cuba to cascade the teaching methodology, skills and ideas to their peers and colleagues within their own and with other regions and provinces. The group was accompanied by members of MES, MINED and the British Council Cuba and a cultural and social programme was organised.

The members of this first group of mentors has certainly been ‘in action’ since they returned! With invaluable support from MINED and MES, they have run in-service training courses for trainee, newly qualified and experienced teachers and also teacher educators all over Cuba and they have spoken at a number of conferences. One of the most striking things about the 3-year programme as a whole has been the enthusiasm of the participants to share their experiences and to act as its ambassadors.

The project is by no means at an end. Both Classrooms in Action and Mentors in Action have the support of the Ministries and further courses are planned which will help to spread ideas and new developments to more provinces in Cuba. The British Council Cuba and the St Giles Educational Trust will continue to work closely with MINED and MES but Mentors in Action is itself an important vehicle though which the programme can eventually be delivered autonomously within Cuba.

Projects such as these are very organic, both in terms of the way in which they are conceived and in the way in which they grow. At the pilot course stage, we could not have envisaged how this project would evolve. The strong working relationship between all parties involved has been key to its success to date and for the St Giles Educational Trust, it has been a privilege to be involved thus far.

Writing in Foreign Language Teaching

Elisabeth Dumpierres Otero, Cuba;Vilma María Pérez Viñas, Cuba;Raquel Guerra Ceballos, CubaAn Overview of English Language Education in Cuba: Achievements and Challenges

Eduardo Garbey Savigne, Cuba;Isora Enríquez O´Farrill, CubaBritish Council-St Giles Educational Trust: Classrooms in Action and Mentors in Action, Cuba

Mike Williams, UKThe ArrowMight Program: Cuba´s Contribution to a Literacy Project for the Canadian Context

Matilde L. Patterson Peña, Cuba