- Home

- Various Articles - Teaching Primary

- The Use of Multiple Intelligence Based Activities to Reduce Students’ Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety While Adapting to a Bilingual System

The Use of Multiple Intelligence Based Activities to Reduce Students’ Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety While Adapting to a Bilingual System

Leyla Saavedra holds a BA in education and teaching of English and an MA in innovation of teaching, learning, and assessment of English, both from Universidad de Concepción (Chile). She is currently working at English Online Program, as part of Universidad de Concepción. Email: leysaavedra@udec.cl

Verónica Yañez holds a PhD in Assesment in Education and an MA in Education. She also holds a BA in Education. She is part of the department of curriculum and instruction at Universidad de Concepción, Chile.

Abstract

The following article is based on an action research study, which aims to describe the contribution of the use of Multiple Intelligences activities in a group of Chilean young learners from 3rd and 4th grade, who were adapting to a bilingual system during their first school term, in order to reduce their levels of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The research was conducted in a semi-public bilingual school located in Concepción, Chile. The intervention was carried out in the English Club, which is a compulsory extracurricular activity for new students in the school. Eighteen students from 3rd and 4th grade participated in the intervention of two sessions, where activities based on the Multiple Intelligences Theory (Gardner, 1986) were implemented. Students’ levels of anxiety before and after the intervention were gathered through a Likert scale. Their perceptions of the intervention were collected through a focus group after the intervention. Data was analyzed using frequency and thematic analysis, respectively. Findings showed a consistent decrease in students’ levels of anxiety after the implementation of the activities. Furthermore, their perceptions about the intervention provided evidence that the use of this methodology seems beneficial, easier to perform and more engaging.

Introduction

According to what the Chilean Ministry of Education (Mineduc) proposes, the subject of English Foreign Language (ELF) is for students to learn English and use it as a tool to deal with simple communicative situations of various kinds (Curriculum en linea, n.d.). However, the lack of practice that students get given the few hours per week in which children are exposed to English, in general, makes difficult for them to develop their language learning (Al Hosni, 2014; Zhang, 2009; Ur, 1996). Moreover, there is a big gap between the regular schools that adopt the Ministry’s study program, and the ones that decide for their own, creating special study programs oriented to bilingual education (Ayudamineduc.cl, n.d.). These schools’ main characteristic is that they impart most of their subjects in the target language, using it in other contexts, trying to encourage students to use it in different situations.

In light of this, it is not difficult to imagine how it is like for a child to move from a regular school where English is just a subject that they check 2 hours a week; to one in which most of the subjects are taught in a foreign language. Consequently, negative emotions, as anxiety, tend to be present all along the learning process and may act as obstacles at the moment of language use and acquirement (Chan & Wu, 2004).

The American Psychological Association poses that anxiety is “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes” (APA.org, n.d.). Baba (2018) points out that students may experience this foreign language classroom anxiety (FLCA) due to the presence of several factors as tests, communication apprehension and negative evaluation. Horwitz (1986) adds factors related to the learner, the instructor, and the institutional practices. For these reasons, it is crucial for teachers to include activities that enhance students’ feeling of comfortability within the classroom environment, reducing their levels of anxiety and helping them to explore their abilities and reach their maximum potential (Altan, 2012).

Based on the previously stated, the action research study in which this article is based, aims to describe the contribution that the use of multiple intelligence theory has on 3rd and 4th grade students’ level of foreign language classroom anxiety while adapting to a bilingual system. Additionally, it has as specific objectives to examine the extent in which the use of these activities reduces students’ levels of foreign language classroom anxiety; and finally, to describe students’ perceptions regarding the use of this methodology.

Conceptual framework

Bilingual schools in Chile

In Chile, English foreign language subject becomes compulsory at school since 5th grade. Before that, schools decide whether they adopt or not the ministry’s proposal for 1st to 4th grade regarding this subject. However, there are some schools that decide for bilingual models. These institutions teach not only the subject itself, but science, history, art, technology and mathematics in English from playground to 5th grade. These programs follow what literature describes as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), proposed by Marsh 1984, which includes the use of a target language as bridge of content communication. As in the country there is currently no study program designed solely for schools that offer bilingual education, these institutions have the right to create their own study program, which is later reviewed and accepted by the MINEDUC (Ayudamineduc.cl, n.d.). Thus, it is difficult to know the parameters in which English will be taught, or what academic requirements students must have at the moment of transferring from traditional to bilingual education.

Teaching English to young learners

Teaching English to young learners requires the ability of teachers to discuss content knowledge, but also the capacity to foster students’ engagement, in order to help them to increase their cognitive development, motivation and attention (Nunan, 2010). Within a similar perspective Cameron (2003) advocates that it is crucial for teachers to increase their skills in order to teach effectively. This entails to get the pupils’ attention and also to keep them mentally active while they are participating in an English lesson. Among the factors that could affect language learning for these students, Yilorm (2018) points out that two of the most important agents regarding learning are related to affective-motivational and behavioral perception of the students. The first one states that elements that enhance language comprehension are related to the motivation, the concern they show for the subject and activities, and the way in which they are aware of the benefits of learning. On the other hand, behavioral perception has to do with the learning environment itself. Children need to feel that they are free to explore language and make all the mistakes necessary without the risk of being mocked at the moment or ever later (Clapper, 2010). The anxiety caused by the feeling of being unable to modify frames could discourage students. Thus, they may feel frustrated, which in turn might lead to language acquirement indifference.

Foreign language classroom anxiety

According to the American Psychological Association, anxiety is described as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure” (APA.org, n.d.). Chan & Wu (2004) state that, within the research area, anxiety can be distinguished into three different perspectives: State anxiety, trait anxiety and specific-situation anxiety. This last one focuses on respondents to experience and manifest their anxiety to particular sources (Chan & Wu, 2004). This emotion is described as the anxiety experienced in a well-defined situation and it is constant in time (MacIntyre & Gardner, 1991). When anxiety arises among language learning situations, it classifies as a specific debilitating anxiety reaction. Baba (2018) points out that students may experience this foreign language classroom anxiety (FLCA) due to the presence of several factors as tests, communication apprehension and negative evaluation. There could be also factors related to the learner, the instructor, and the institutional practices (Horwitz, 1986; Sulimenova, 2012). Huang, Eslami and Hu also mention that peers have higher levels of influence on students (2010). Arnold (2000) declares that anxiety could start in early stages of language learning, so the emotion could lead students to associate anxiety with the target language itself. Moreover, foreign language learners often express feelings of stress, nervousness or anxiety while learning to speak the target language (Suleimenova, 2012), as they claim to have “mental blocks”. They face similar situations when their perceptions regarding their peers or teacher are negative. To avoid this, teachers must work on reducing anxiety levels by helping learners to recognize their own discomfort and orient them to establish achievable goals, reasonable in regards to their learning stages (Horwitz, 2001).

Multiple Intelligences in EFL context

The theory of multiple intelligences (MI) was proposed by Gardner in 1983. There, he abandoned the idea of sticking to one pragmatic intelligence and argues that there are eight different kind of intelligences according to the different ways in which people acquire, use and remember knowledge through time. These are: Verbal -linguistic intelligence, logical-mathematical intelligence, spatial intelligence, musical intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, intrapersonal intelligence and naturalistic intelligence. Many studies support the idea that human beings perceive and process information in different ways, thus, MI theory is a reliable answer to these differences. Moreover, according to Liu and Chen (2014) one important aspect of the multiple intelligence theory is that various intelligences work at the same time instead of just one working prominently. This means that even though people could feel identified with a particular method to learn, this does not mean that it is impossible for them to understand and internalize in different ways.

Throughout the years, different studies have implemented this methodology in order to improve EFL acquisition from the perspectives of vocabulary, writing, instructions, proficiency and motivation (Ghamrawi, 214; Günduz & Ünal, 2016; Kim, 2009; Hou, 2016; Altan, 2012). However, there is no previous research combining the use of MI to reduce anxiety levels specifically in the context of students moving from traditional to bilingual schools. Thus, my research interest has to do with helping a group of students in the transition they are facing from a traditional to bilingual system.

Methodology

Research Question

How does the use of multiple intelligence activities influence the levels of anxiety of a class for 3rd and 4th graders adapting to a bilingual system?

Specific Objectives

- To examine the extent to which implementing multiple intelligence activities reduces students’ levels of anxiety in the EFL lesson.

- To describe students’ perception towards multiple intelligence activities in relation to their anxiety levels.

Participants

This action research was carried out in a bilingual semi-public school in Concepción, Chile; with a group of 18 students aged between 8 to 10 years old from 3rd and 4th grade as participants. 2019 was their first year immersed in a bilingual system and they presented difficulties at the moment of participating actively in the classroom, despite the fact that 3rd and 4th graders have 14 pedagogical hours exposed to English language, as the subjects of science, social studies, art and technology besides English subject are taught in the target language. For this reason, the school has implemented a workshop named English activities club in which they have two additional pedagogical hours of practice per week. In this workshop, the intervention took place.

Field Notes in Classroom Observation

Mason (2002, p. 85) states that “classroom observation at some point reveals the generation of multidimensional data on social interactions in specific contexts as it occurs”. In this study, lessons were observed one week before the Multiple Intelligence based activities were implemented, and they were oriented to pursue the first objective which is to check students’ levels of anxiety when they face speaking activities in front of their peers and the teacher. The purpose of using this technique was to become familiar with students’ classroom environment in order to address better their weaknesses at the moment of implementing the intervention activities. The field notes were taken by the researcher in class as cryptic jotting and complemented by self-audio-recordings (Berg & Lune, 2017) with the purpose of complementing and reflecting on the researcher’s practice and students’ reactions.

Children Foreign Language Anxiety (Likert) Scale

In 1986, Horwitz designed a specific Likert scale to determine anxiety levels, which was called Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale. This instrument was claimed to be one of the most effective when it comes to measure anxiety in teen and adult students (Aydin, 2016). Thus, in 2017, Aydin validated the adaptation for young EFL Arabian students, and it was called Children Foreign Language Anxiety Scale (CFLAS) which is more precise and appealing for young learners. Based on these notions, this researcher aimed to apply an adapted Spanish version of Aydin’s scale, considering the most important dimensions seen as factors that might affect the sample, to collect data about students’ anxiety levels.

The adjusted scale was validated All the comments received from the experts were considered to improve the instrument. The final version of the scale was piloted before its actual implementation. When the Likert scale was administered to the students, the questions were socialized in order to clarify the meaning of every question so all participants could understand the same purpose behind each item.

The focus group

The purpose of carrying out a focus group at the end of the action research implementation was to gather students’ perception towards multiple intelligence activities in relation to their anxiety levels. Hence, the focus group included only five questions with the respective probing questions (Villard, 2003) that emerged from the conversation. Questions were classified only into two different categories regarding the participants’ perception towards English lessons in general, and their perceptions on the intervention.

The questions were also validated by two teachers in the school where the intervention was applied. The parents of the participants were requested to sign a consent for the children to be audio-recorded. The day of the focus group, six children who participated in both intervention sessions were chosen (Gibson, 2007). Before the questions were presented, they were informed of the rules of the activity. Just like the Likert scale, this instrument was also designed in the students’ mother tongue, Spanish, in order to avoid students’ confusion or misunderstandings; and also for them to express their perceptions clearly.

Data and Discussion

Specific objective - One

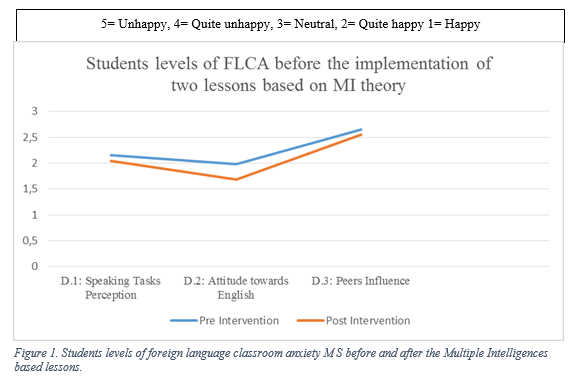

One of the purposes of this study was to examine to what extent, if any, the implementation of multiple intelligence activities influenced students’ anxiety levels regarding the EFL lessons. The results obtained from the Pre and Post Likert scales evidenced that, according to the mean scores’ differences, there was a decrease, even though it was slightly, of anxiety in the three dimensions considered as anxiety factors. Figure 1 below illustrates the decrease of anxiety levels of students after the two session interventions.

In relation to students’ perceptions on speaking tasks, questions from the Likert scale were oriented to determine which situations in specific made student feel more or less anxious. The results that presented higher changes were the ones related to the opportunities to speak in English (From 1,7 to 1,2). It is important to mention that during the first lesson observed, students resisted to speak in the target language. Nevertheless, they volunteered and participated actively during lesson interactions which involved speaking tasks, as self-recordings exemplify. All this might indicate that after the implementation of MI activities, students felt more confident, or in a safer environment (Clapper, 2010). Post intervention, results came closer to the lowest emotion, demonstrating that in general, these kind of activities make these participants more comfortable.

Regarding students’ attitude towards English language, data collected through the Likert scale and complemented with the field notes suggests that their attitude towards the language improved, as learners’ levels of anxiety diminished in this category. The most notorious change was associated to the feelings of students when someone spoke English near them. In this aspect, anxiety mean score reduced from 2,3 to 1,8. In this context, Arnold (2000) explains the importance reducing the constant error correction or drawing attention to activities that require self-investment in front of others. With reference to this, Hou (2016) poses that the use of Multiple Intelligence activities could improve students’ tolerance towards a specific subject and their performance in this, which could have been the case with these participants. It is also important to highlight that during the observation period, students showed a clear preference towards activities presented with games, and during the focus group they linked this preference to the Multiple Intelligence activities. Thus, it could be argued that the intervention contributed positively to the participants’ anxiety levels regarding attitude towards English because of the way the lesson activities were presented, including several MI tasks oriented to different intelligences while trying to reinforce the same content.

Regarding the last anxiety factor, data indicates that before the intervention, students had higher levels of concern in relation to their peers’ views when they face learning English activities. Mean score of the first Likert scale varies from 1,3 to 3,8; which is at this level, the highest anxiety indicator. On this subject, literature describes classmates’ support as essential to language learners due to the time they spend together and the importance that children give to their peers’ opinions (Huang, et.al., 2010). Multiple intelligence activities consider the idea of group work as part of interpersonal intelligence, where learners should have the chance to solve problems by interacting and reaching agreement in teams (Luengo, 2014). This is also illustrated by the results of the post intervention as is suggested by data from the Likert scale. From the five questions used as indicators of anxiety regarding this dimension, four of them decreased although slightly. However, in the question from the Likert scale regarding feelings when classmates laugh at me, mean score after the intervention increased from 3,8 to 4,3. This could be due the importance that each participant gave to the sample group, considering that it was smaller than their traditional class group. Additionally, from the extracts of the self-recordings, there are moments when students manifested their preference for working with their classmates during the intervention, and the comments collected during the focus group evidence that team work is something that they enjoy and consider useful for their learning process.

Specific objective - Two

The second specific objective of this study was to gather students’ perceptions on the implementations of lessons based on the Multiple Intelligence theory. The data was gathered through a focus group and analyzed with thematic analysis. Extracts from the focus group and self-recordings, support the idea about how the implementation of Multiple Intelligence Theory results beneficial for students’ learning process, as they perceived these type of activities as more comfortable tasks to perform successfully.

One of the main topics that needs to be highlighted attention was students’ honesty regarding they discomfort when writing and speaking in the target language. In this sense, they contrasted the idea saying that they enjoyed the intervention because there were games and not presented as homework. This results interesting, because during the interventions students were actually requested to write and speak. However, the presentation of the activity was projected, they were allowed to work with partners if they wanted to, and they had the chance to use their mother tongue to clarify some doubts. Thus, it could be argued that creating the adequate environment, the four main language skills could be practiced in this context (Clapper, 2010).

Participants did not reach an agreement about their favourite activity during the intervention. However, there were repeated comments about enjoying group work support the idea that the interpersonal intelligence during lessons promotes critical thinking and collaborative learning (Luengo, 2014). In contrast to this, there is evidence collected from the self-recordings which might prove that some activities that were part of the traditional evaluation system as logical-mathematical or linguistic, encouraged students to work independently (Dueñas, 2003). Besides, other thing that students kept repeating was how much they enjoyed the activities in which they “had to do things”. Kudryashova et.al., 2016) describes this as active role or active learning and it is characterized by learning opportunities that allow the students to construct meaning by connecting with prior knowledge, socializing and developing authentic tasks. Finally, activities regarding kinaesthetic, visual-spatial and musical intelligence, contributed to support content and given the comments during the focus group, these remained in students’ memory as meaningful, and easier to perform than regular classroom activities (Ghamrawi, 2014).

Limitations and further study

As a result of this action research study, it was acknowledged that the use of multiple intelligence based activities help to reduce students from 3rd and 4th grade levels of foreign language classroom anxiety in the context of adapting to a bilingual system.

The findings presented along this action research study have contributed to the planning period conducted after this intervention, which hopefully will improve students’ learning and performance. Therefore, possible practical applications could consider some modifications or improvements, as, for example, replicate the same study, but in a longer period of time. It could also be included to work with students from other levels to compare results according their age range. As it was mentioned previously, due to the size of the sample, results might have varied from a bigger group of students. Thus, another option could be having this intervention integrated in the English lesson, or any other lesson taught in the target language that involved a wider sample, instead of having it as a complementary subject like in this case. Moreover, lessons could be either separated to address a different intelligence at a time in each class. At the end, as part of the Likert scale application, ask which lesson or lessons made participants feel more comfortable; or could be divided into control and sample groups to compare their performances in time. Insights extracted from the focus group had contributed directly to the perceptions and improvements that, as a teacher, one is able to make in order to engage students to the lesson. It is the desire of this practitioner that these contributions will motivate other professionals to study in depth the implementation and further investigation of this approach to enhance students’ integration into bilingual classrooms.

Conclusion

The present study has not only accomplished its general purpose to reduce students’ levels of FLCA while adapting to a bilingual system, but it has served to this researcher’s own teaching practices as a way to remember the importance of being aware of the differences among the students. It has shown how significant it can be to create a safe classroom atmosphere in which all members feel free to experiment with language with different learning opportunities, interacting with others and having time to reflect on their own work.

References

Anxiety. (n.d.) American Psychological Association. Retrieved on December 15th, 2018, from https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety/

Al Hosni, S. (2014). Speaking Difficulties Encountered by Young EFL Learners. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL), 2 (4), 22-30.

Altan, M. (2012). Effects of Multiple Intelligences Activities on Writing Skill Development in an EFL Context. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 32 (32) , 57-64 . DOI: 10.9779/PUJE474

Arnold, J. (2000). Seeing through listening comprehension exam anxiety. TESOL Quarterly, 34 (4), 777-786.

Aydın, S., Harputlu, L, Uştuk, Ö., Güzel, S., & SavranÇelik, Ş. (2017). The Children’s foreign language anxiety scale: reliability and validity. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 13(2), 43-52. ISSN: 1305-578X

Ayuda Mineduc: Atención ciudadana del Ministerio de Educación del Gobierno de Chile (n.d.) Ayuda Mineduc. Retrieved on November 3rd, 2019, from https://www.ayudamineduc.cl/ficha/reconocimiento-oficial-5

Baba, Y. (2018). English Language Anxiety and the Big Five Personality Factors. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 8, 191 -200. ISSN 2220-8488

Berg, B. L. 1., & Lune, H. (2012). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Cameron, L. (2003). Challenges for ELT from the expansion in teaching children. ELT journal, 57(2), 105-112

Chan, D. Y. C., & Wu, G. C. (2004). A study of foreign language anxiety of EFL elementary school students in Taipei County. Journal of National Taipei Teachers College, 17(2), 287-320.

Clapper, T. C. (2010). Creating the safe learning environment. PAILAL, 3(2), 1-6.

Inglés. (n.d). Currículum Nacional. Retrieved on December 15th, 2018, from https://www.curriculumnacional.cl/614/w3-propertyvalue-52050.html

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. Chicago, 15th ed.

Gibson, F. (2007) Conducting focus groups with children and young people: strategies for success. Journal of research in nursing. 12(5) 473–483 DOI:10.1177/

Gündüz, Z. & Ünal, I. (2016) A Teachers’ Action Research: Diminishing Students’ Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(7): 1687-1697. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2016.040722

Ghamrawi, N. (2014). Multiple Intelligences and ESL Teaching and Learning: An Investigation in KG II Classrooms in One Private School in Beirut, Lebanon. Journal of Advanced Academics, 25(1), 25-46. DOI:10.1177/1932202X13513021

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112– 126

Hou, Y. (2016). The Impacts of Multiple Intelligences on Tolerance of Ambiguity and English Proficiency— A Case Study of Taiwanese EFL College Students. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 6, 255-275.

< >Huang, S., Eslami, Z., & Hu, R.-J. S. (2010). The Relationship between Teacher and Peer Support and English-Language Learners’ Anxiety. English Language Teaching, 3(1), 32–40. DOI:10.5539/elt.v3n1p32

Kim, I. (2009) The relevance of Multiple Intelligences to CALL instruction. The reading matrix. 9 (1) 1-21.

Kudryashova, A.; Gorbatova, T.; Rybushkina, S. & Ivanova, E. (2016) teacher's Roles to Facilitate Active Learning. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 7 (1). 460 - 466.Doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n1p460

Liu, H. & Chen, T. (2014). Learner Differences among Children Learning a Foreign Language: Language Anxiety, Strategy Use, and Multiple Intelligences. English Language Teaching, 7, 1-13. 2018. doi:10.5539/elt.v7n6p1

Luengo, E. (2015) Learning styles and multiple intelligences in the teaching-learning of Spanish as a Foreign Language. Enseñanza & Teaching,33, 79-103.

MacIntyre, P.D., & Gardner, R. C. (1991). Investigating language class anxiety using the focused essay technique. The Modern Language Journal, 75, 296-304.

< >D. (2010). Teaching English to young learners. Anaheim, CA: Anaheim University Press. Ur, P. (1996). A course in language teaching.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Suleimenova, Z. (2012). Speaking anxiety in a kazakhstani foreign language classroom. Sino-US Engish Teaching, 1766-1774.

Yilorm, Y., Acosta, H., & Martinez, E. (2019). Desarrollo de la habilidad comprensión auditiva de la lengua inglesa en estudiantes socialmente vulnerables. ATENAS. Vol.I, N°. 33, p. ISSN: 1682-2749.

Zhang, S. (2009). The role of input, interaction, and output in the development of oral fluency. English Language Teaching,2(4),91–100.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Through Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

The Use of Multiple Intelligence Based Activities to Reduce Students’ Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety While Adapting to a Bilingual System

Verónica Yáñez Monje, Chile;Leyla Saavedra Saavedra, ChileThe Meaning of Teacher Centeredness in The Teaching English to Young Learners Curriculum Design

Thi Minh Huyen Nguyen, Vietnam;Ngoc Tung Vu, Vietnam