Language Learning Technologies: A Study

Letizia Cinganotto, PhD, Researcher at INDIRE (National Institute for Documentation, Innovation, Educational Research, Italy). Her main research areas are CLIL, language teaching/learning and technologies, teacher training, school innovation. She is involved in different Working Groups and Committees both at national and international level.

Abstract

The paper is aimed at investigating teachers’ beliefs in using learning technologies for language learning and for CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning). Starting from a brief outline of the latest research in the field of technology-enhanced language learning, the paper will describe the main outcomes from a questionnaire delivered by the author to 228 teachers from across the world attending a free MOOC. The questionnaire was meant to understand the teachers’ reactions to the use of technologies for learning and teaching English, in order to ascertain what added value web and digital media can contribute to different aspects of the teaching and learning process. The paper will also try to add volume to the teachers’ voice by reporting directly some of their comments and notes.

Introduction

The massive use of technologies which is reshaping the organization and the setting of school learning environments implies rethinking teaching practice, integrating learning technologies throughout the whole process.In particular, learning technologies may represent an added value to the teaching of a subject in a foreign language, in our case English. The research design which will be presented here places itself within this background, with the aim to investigate the perceptions of a sample of teachers attending a MOOC with regard to the use of technologies for teaching a subject in English.

The question behind the research design was the following:

- What are the teachers’ beliefs on learning technologies for teaching and learning English and/or a subject in English?

The research design places itself within a vast literature in the field of language learning technologies, which will be briefly outlined. In order to find answers to the question above, a questionnaire was delivered to a sample of teachers from all over the world, aimed to investigate their perceptions and beliefs about the potential of learning technologies for teaching and learning English or a subject in English, as in CLIL methodology (Cinganotto, 2018). Ideas, suggestions and comments from the teachers will be also collected and commented on.

After a brief overview on Technology-Enhanced Language Learning, the paper will describe the methodology of the research, the profile of the respondents and the main outcomes from the data analysis. From the respondents’ comments and feedback, general positive beliefs towards the use of technologies can be assumed.

Technology-Enhanced CLIL: background

Acquiring a foreign language is a long, natural process (Lightbown & Spada, 2006), therefore considerable exposure to naturally occurring language is necessary to ensure the achievement of a good level of competence: learners need to have access to spontaneous speech, in an interactive context where they can concretely experience the functioning of the foreign language: learning technologies (Hockly, 2016) can provide such an interactive, multi-functional and meaningful learning environment, taking advantage of a wide range of dynamic and engrossing multimodal techniques and strategies, which can help put the learner at the centre of the learning pathway.

A wide range of studies has recently proved the potential of learning technologies for language learning and for CLIL, in terms of students’ learning outcomes and teachers’ innovative teaching strategies.

Pokrivčáková et al. (2015) widely use the expression “Technology-enhanced CLIL classroom”, which refers to the integration of CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning) or MALL (Mobile Assisted Language Learning) in a CLIL environment. Both the approaches are aimed at fostering and improving authentic language for communicative purposes and at practising language and cognitive skills through the use of tasks and hands-on activities. Littlewood (2004:324) also considers Task-Based Language Teaching as “a development within the communicative approach”, in which the crucial feature is that communicative “tasks” are not only components of the methodology but also units of an entire syllabus.

Task-based language learning and teaching with technology have been considered closely interconnected and complementary (Thomas & Reinders, 2010): through the use of technology learners are highly motivated to carry out tasks and this can positively impact students’ learning outcomes.

A wide range of studies have focussed on the combination of TBLT and CALL (Hampel, 2006). In fact, CALL is constantly increasing in popularity among teachers and learners, as it can meet the students’ needs and help teachers innovate their teaching strategies. These aims can also be reached thanks to the use of MALL approach, which refers to mobile devices, not only as communication tools but also as learning tools: in particular, mobile learning has turned out to be particularly effective in the improvement and expansion of vocabulary (Duman et al. 2015). Other studies have shown the effect of CALL on listening comprehension (Brett, 1997) and on reading comprehension (Murphy, 2007). The weakest skills in CALL have turned out to be the speaking skills: most CALL-based teaching and learning has tended to focus on non-oral activities such as software or Web-based reading, writing, or gap-fill type activities, considering oral pair and group role-plays and discussions as aspects peculiar to face-to face learning.

CALL and MALL can have a huge potential in language learning as they add the multimodal dimension, i.e.

“the use of several semiotic modes in the design of a semiotic product or event, together with the particular way in which these modes are combined – they may for instance reinforce each other […], fulfil complementary roles […] or [be] hierarchically ordered” (Kress, van Leeuwen, 2001: 20).

According to Levy, digitally mediated communication is creatively multimodal, including

“multi-purpose, multifunctional technologies that involve layers of complexity and application in L2 learning that are unique among the technologies of the modern world” (Levy, 2009: 779).

The potential of multimodal environments has been highlighted by a wide range of scholars with reference to the language field:

“The widespread availability and sophistication of multimodal communication tools have captured the imagination of practitioners and scholars alike, who have identified interesting learning opportunities and fields of enquiry for language teaching” (Calvo-Ferrer et al., 2016: 247).

The explicit link between CALL and CLIL has been recently highlighted by the literature (Stoller 2008), even if there is a call for further investigation in this direction.

The integration of learning technologies in a foreign language or a CLIL environment was strongly supported by the 2014 European Commission report, titled “Improving the effectiveness of language learning: CLIL and Computer Assisted Language Learning”, which mentioned the following successful criteria: teacher training with proper pedagogical design, effective adoption and integration; teaching approaches including selection of online materials; adoption of student-centred learning; learning processes with references to constructivist tools and game-based tools (p. 28).

The study: methodology and participants

The aim of the study was to investigate the perceptions and reactions of a sample of teachers to the use of learning technologies for teaching English or a subject in English, in the context of a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) on FutureLearn platform.

A questionnaire was planned to investigate the teachers’ beliefs about the use of learning technologies for English Language Teaching and for CLIL. The questionnaire was made up of both closed and open questions: relevant comments and notes were grouped and commented on by using the “Framework Analysis” (Ritchie et al. 2014) as a qualitative research method.

Taking into account baseline positive attitudes to online and digital aspects of learning, the MOOC participants were deemed a good target for the survey.

Profiling the participants

The survey was launched in April 2017 and was delivered to the participants registered for the winter edition of the MOOC.

228 teachers answered the questionnaire: the largest nationality represented was Italian (26.8%) followed by Spanish (18%); the other respondents were from a number of other countries across the world, for example UK, Russia, Mexico, Portugal, Kazakhstan, Colombia. They were mainly teaching in state schools (53.5%). 35.5% of them worked in schools which provided an international curriculum. 64% of the participants were upper secondary school teachers, with 11 or more years of work experience. The majority of respondents taught English as a foreign language (73.3%), but there were also some teachers of Italian (11.8%). Their level of English according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) was generally high: C2 (36.4%), C1 (32.5%), and B2 (26.3%).The lower levels were distributed over the remaining smaller percentages.

The majority of the respondents stated they had excellent (14.9%), very good (31.6%) or good (33.8%) competences in using technology ‒ a very encouraging figure, showing positive attitudes towards learning technologies for CLIL.

One question in the survey aimed at investigating the participants’ previous experience in teaching a subject in English: 39,47% regularly taught a subject in English, while 31,14% had some experience in this field, 12,28% were experienced teachers of a subject in English and also a trainer to other teachers; the remaining respondents were totally inexperienced.

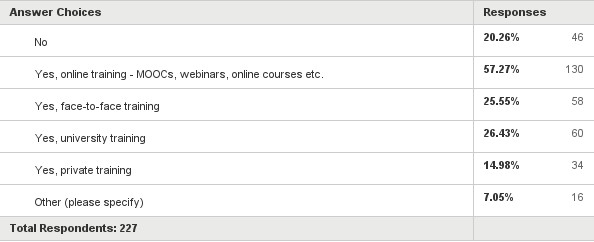

The questions aiming at eliciting the respondents’ previous training initiatives on CLIL in English is particularly meaningful, as online training events or MOOCs got a quite high percentage of answers (57,27%), as in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 – Previous training initiatives on CLIL in English

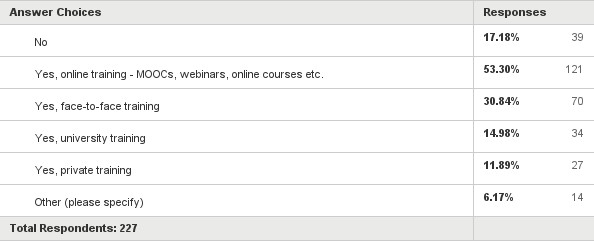

A very similar result comes from the parallel question relating to previous training initiatives on using technology for teaching and learning: 53,30% attended MOOCs and similar online initiatives (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 – Previous training initiatives on using technologies for teaching and learning

The level of competence in using technology for teaching was generally high: about 80% of them stated they had a good/very good/excellent level of competence. Only about 20% answered sufficient/weak.

The target was quite skilful both in the use of technologies and in the teaching of a subject in English.

Results and discussion

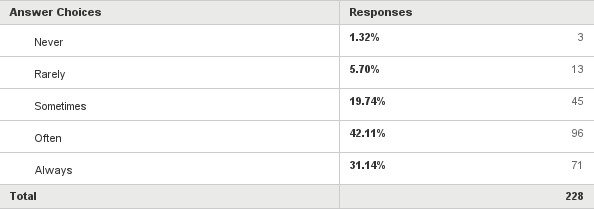

The first question was aimed at investigating the teachers’ habits and frequent use of learning technologies. The answers to the question “How often do you use digital tools and resources in your teaching?” are registered in the table below:

Fig. 3 – Use of digital tools in the teaching practice

42,1% of the respondents answered “often” and this is a very positive datum, as it means technology is becoming crucial to teaching practices.

The answer to the question “Do you use classroom teaching materials from the internet?” leaves no doubt: 92.9% of the respondents answered “yes”, confirming the crucial role of the web in the teaching process, in particular in finding materials and resources for the different activities.

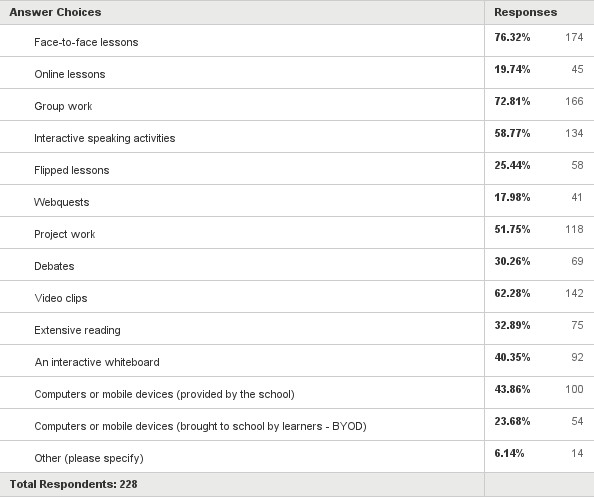

One question was aimed at understanding the main habits of the respondents as far as the different teaching strategies were concerned: “Which of the following do you use when you teach subject lessons in English?” The table below collects the results: unfortunately, a high percentage (76,32%) still uses face-to-face lessons for teaching a subject in English: a traditional, bottom-up format which CLIL methodology tends to replace with more active, interactive and multimedia strategies. 62,8% of the respondents use videoclips during the lesson and this is an encouraging outcome: videos can be very effective in an English or a CLIL lesson for different purposes. Videos can also represent a crucial part in a flipped classroom: 25,44% of the respondents adopted the flipped model.

An interesting issue concerns the use of computers or mobile devices provided by the school (43,86%) or brought to school by the students as in BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) (23,68%): the use of computers, laptops and mobile devices is increasing and is becoming more popular in the CLIL curriculum, but some resistance still remains against the use of personal devices brought in by the students.

Fig. 4 – Teaching strategies for language learning and CLIL

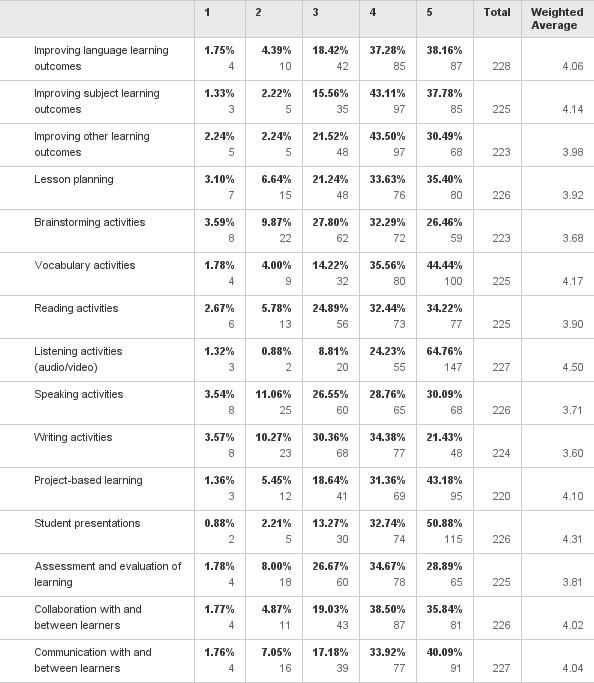

The question aimed at investigating the perception of the added value of technologies in teaching a subject in English is the following: When you teach a subject in English, how much value do you think technology adds to the following aspects (1 = technology adds no value, 5 = technology adds a lot of value)?

The highest value (m = 4.5) was registered for listening activities. Audio oral skills are often complicated to practise in the classroom as these skills need specific support. Technology can help for example, with the use of videos, podcasts and movie clips etc. that can be used within an ESL or a CLIL activity. The second highest value was for students’ presentation (m = 4.3): a wide range of teaching strategies and techniques can take advantage of technology to share students’ individual or group work with the teachers and with their peers, such as webquests, Task-based Language Learning and PBL (Project-based Learning). Technologies can help create multimedia products as individual or collective and cooperative work to be shared in class or to be assessed by the teachers or their peers. Vocabulary activities also scored highly (m = 4.2): there is a wide range of online dictionaries, translating tools and other web tools which are specifically designed to practise and extend vocabulary. Many other options also scored well: collaboration and communication with and among learners (m = 4), lesson planning (m = 3.9), reading activities (m = 3.9), assessment (m = 3, 8). The lowest score was for writing activities (m = 3.6). The reason for this could be that in order to develop writing skills in English, teachers prefer “traditional” pen and paper. However, there is a wide range of tools designed to help students practise their writing skills and some of the following were mentioned by the respondents: “Storybird”, for digital story-telling; “Write&Improve”, for improving writing skills; and tools for blogs or wikis (eg. “Wordpress”, “Wikispace”).

Fig. 5 – Teachers’ perceptions on the added value of technologies for language learning

The comments collected through the questionnaire as answers to the question: “In your opinion, what are the benefits of introducing the use of digital tools and resources into your curricula?” have been grouped in two categories, according to the Framework Analysis:

- the potential for teachers

- the potential for students.

The potential for teachers

The majority of the comments highlight the potential of ICT in terms of teachers’ innovative and successful teaching strategies. These are some of their remarks:

“Excellent source of learning, understanding how to use different digital tools, to make creative mind to students.”

“Keeping up with the times.”

“There is more sharing and quick communication.”

“The benefits of the use of digital tools and resources are the most outstanding! They help us to teach more easily and comfortably, pupils like to use video clips and cartoons in English”

“It is more attractive and easier and helps students to understand the topic because it is more interactive and visual, and you could show more media resources.”

“Boosting 21C skills; introducing new methodologies s.a. Flipped Classroom, Blended Learning, Peer Review.”

“Digital resources broaden the possibility of offering the students a large number of different learning objects, so that they can meet different learning styles. Videos and interactive simulations are much more captivating than text books and in addition, they spur the students to work independently and be creative. Last but not least, digital tools are the most common tools for today’s students, who are very familiar with and enjoy using them.”

“There are a lot of resources that are easy to find if teachers and students know how to look for the correct ones. Saving time and having fun learning new things.”

“Effective technology integration is achieved when the use of technology is routine and transparent and when technology supports curricular goals.”

“Technology motivates and challenges the teacher, who can actually learn a lot from his/her learners too - role reversal which is very satisfying for the students especially - but also changing the type of lessons delivered which adds pace, makes them more memorable, more hands-on, more collaborative, more self/peer assessed, and so on”.

The comments made by the respondents point out the potential of technologies in making the lesson more interactive, engaging and effective in order to foster retention and enhance learning outcomes. It seems to be perceived as a need: teachers must innovate their teaching techniques in order to keep up with the progress of the Knowledge Society. These remarks summarize the teachers’ point of view: technology motivates and challenges the teacher and the students as a consequence.

The change of paradigm is particularly interesting: teachers must be trained to use technologies in the right way and they can also learn from their students (“role reversal”).

This remark draws the attention to the particular role of the teacher: a moderator and facilitator, who masters the content, the context and the target and adjusts the use of technologies accordingly, as the following comments highlight:

“Always remember that they are only tools; their benefits depend on the context the teacher operates in.”

“It is useful because it can bring more ideas for presenting a more interactive class that is attractive to students and motivates them. The problem would be the lack of adequate resources at the schools, the large amount of investment required, and teacher training on how to use technology in the classroom.”

These final comments refer to some critical issues related to learning technologies, such as the need for adequate resources and investments in technologies at school and the teachers’ need to be properly trained in the use of ICT as an integral part of the curriculum and as a means to support the learning goals.

The potential for students

The majority of the comments highlight the potential of ICT in terms of students’ motivation and learning outcomes. These are some of the respondents’ remarks:

“It allows more focused teaching, tailored to students’ strengths and weaknesses, flexibility of ‘anytime, anywhere’ access, opportunities to collaborate on assignments with people outside or inside school.”

“It’s a good idea as long as the students don't abuse it!! Like sending messages in class and surfing the net instead of paying attention in class. I have to be very strict when and how they use their iPad during my lessons.”

“Makes a task easier in less time; it may be fun for the students (e.g. Kahoot).”

“Students' attention and motivation are amplified by the use of technologies in the classroom.”

“Students are digital natives and with digital tools teachers speak the language of their students.”

“Learning through audiovisual medium is an effective one as the learners tend not to forget such activities.”

“Students have a clearer overview of course objectives and expectations, have resources that direct and support their study activities available 24/7. Technology can also support students with dyslexia better. They may lower students', institutional and teachers' expenses especially when open access tools are used.”

“You are more likely to keep your students’ attention if you use audiovisual aids. Students are used to using digital devices in their daily life, so they feel comfortable learning with them. It is very important because it's their environment, we now live surrounded by technology.”

“Digital resources allow personalisation of course content, they stimulate different types of learners (visual/auditory), they are great confidence boosters as students' comprehension skills improve and they allow a virtuous learning circle to get started boosting self-directed study and real participation in the classes.”

These remarks show that teachers recognize the potential of ICT for their students: they can be more motivated and more engaged in the activities by using learning technologies, even if there are still some teachers who “have to be strict when and how they use their iPad during the lessons”.

This is part of the teachers’ training needs: they need to be trained on how to use ICT for personalizing their teaching according to the different learning styles, from an inclusive perspective as well. Audiovisual and multimedia aids will help students feel more comfortable at school, avoid feeling that their digital and multimedia habits outside school are disconnected from their traditional, linear, “pen and paper” habits at school.

Conclusions

The research was designed to investigate the added value of learning technologies in teaching and learning English or a subject in English according to the perceptions of a sample of teachers (228) attending a MOOC run by FutureLearn.

A questionnaire was delivered to the teachers who had enrolled in the first version of the MOOC. The teachers who responded had a high level of awareness of using technologies in teaching a subject in English as they had already attended other online training initiatives both on CLIL and on learning technologies, moreover, this was confirmed by the data analysis.

Their perceptions and feelings toward the use of technologies were generally positive: they regularly access the internet for materials and ideas to use during their lessons; they think that technologies can have a strong impact on their teaching practices and on the development of the students’ skills, in particular audio oral skills, vocabulary skills and student presentations.

As the literature shows, the use of multimedia and digital tools for language learning and CLIL has huge potential. However, this potential must be realised by the teacher who continues to have an indispensable role as a facilitator of learning processes and knowledge building.

The answers to the research question were very interesting and stimulating:

What are the teachers’ beliefs on learning technologies for teaching and learning English and/or a subject in English?

The teachers have a positive idea of the use of learning technologies for teaching and learning English or a subject in English. From the wide range of webtools and apps mentioned with reference to the different language skills and to the different activities involved in the teaching/learning process (lesson planning, presentation, project work, assessment etc.), it is easy to understand how skilful in the digital and multimedia field the teachers are: they are keen on using specific tools according to the particular teaching and learning needs. They are technology-sensitive and strongly believe in the power of learning technologies for CLIL in English.

The comments and notes collected through the questionnaire show that the respondents believe learning technologies are powerful and crucial in all the steps of the teaching and learning process.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to Juliet Wilson, director at Cambridge Assessment English, for her cooperation at the project discussed in the article.

References

Brett, P. A. (1997). ‘A comparative study of the effects of the use of multimedia on listening comprehension’. System 25 (1), pp. 39-54.

Calvo-Ferrer, J.R., Melchor-Couto, S., Jauregi, K. (2016). ‘Multimodal Environments in CALL’. ReCALL, Volume 28, Issue 3, pp. 247-252.

Cinganotto, L. (2018). Apprendimento CLIL e interazione in classe. Rome, Aracne.

Duman, G., Orhon, G., Gedik, N. (2015). ‘Research trends in mobile assisted language learning from 2000 to 2012’. ReCALL, 27(2), pp. 197-216.

Hampel, R. (2006). ‘Rethinking task design for the digital age: A framework for language teaching and learning in a synchronous online environment’. ReCALL 18 (1), pp. 105-121.

Hockly N. (2016). Learning Technologies, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Kress G., van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication, London, Arnold.

Levy, M. (2009). ‘Technologies in use for second language learning’. Modern Language Journal, 93 (1), pp. 769–782.

Lightbown, P., Spada, N.M. (2006). How languages are learned, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Littlewood, W. (2004). ‘The task-based approach: Some questions and suggestions’. ELT Journal, 58 (4), pp. 319–326.

Murphy, P. (2007). ‘Reading comprehension exercises online: The effects of feedback, proficiency and interaction’, Language Learning & Technology, 11 (3): pp. 107-129. 63.

Pokrivčáková, S. et al. (2015). CLIL in Foreign Language Education: e-textbook for foreign language teachers, Nitra, Constantine the Philosopher University. 282 s.

Ritchie J., Lewis J., Nicholls C.M., Ormston R. (2014). Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, London, Sage.

Stoller, F. (2008). ‘Content-based instruction’. In N.H. Hornberger, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Vol. 4 – Second and foreign language education. New York: Springer, pp. 1163–1174.

Thomas, M., Reinders, H. (2010). (Eds.) Task-based Language Learning and Teaching with Technology, New York, Continuum Publisher.

Please check the Creative Methodology for Using ICT in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Mobile Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Language Learning Technologies: A Study

Letizia Cinganotto, ItalyGlobal Awareness for the 21st Century. Environmental Education in ELT Coursebooks

Ka Hang Wong, AustraliaLife is a Journey. A Creative Project

Milka Hadjikoteva, BulgariaAn MI Lesson Around the Poem: The Rime of Ancient Mariner, by S.T. Coleridge

N Shesha Prasad, IndiaPoems as Creative Writing Activites for ESL Students

Mihaela Schmidt, Croatia