- Home

- Various Articles - Teaching Adults/Advanced

- Making the Pieces Fit - ELT Curriculum Renewal in Cuban Universities

Making the Pieces Fit - ELT Curriculum Renewal in Cuban Universities

Roadshows

The annual British Council ELT Roadshow takes a teacher development event to universities all over Cuba. In January 2018, the Roadshow lived up to its name, and Dr Claire Whittaker (McIlwraith Associates) and I travelled by road from Santiago de Cuba in the extreme southeast of the island to Holguin, then to Villa Clara, and ending in Havana – a road trip of some 750 kilometres – with two-day workshops in each location. With invaluable support and guidance from Dr Eduardo Garbey Savigne of the Havana Medical Sciences University, our talks and workshops dealt with communicative methodology and the application of the CEFR to the use of a newly-adopted coursebook (face2face). The coursebook had been well received by teachers and students alike, and we concentrated on adaptation strategies and developing teachers’ skills in making the best use of the material. In each of the universities we visited the teachers were responsive and highly committed, and despite limited access to / availability of resources, many of them displayed an impressive level of professional awareness.

In response to our feedback, the British Council, Cuba organised an expanded version of the Roadshow in May 2019, which involved two teams delivering parallel three-day workshops, (Claire and I returning to Villa Clara and Havana, and Robert Williams (University of Westminster) and Tom Connelly (for TransformELT) going to Santiago de Cuba and Holguin. This time we focused more intensively on the CEFR as a basis for the assessment of listening and speaking skills. Again, participants were highly engaged and keen to develop their assessment practices, though it was clear that the Roadshows were one of the few such professional development opportunities available to them.

Although our experience of the Roadshow had been positive in itself, we were acutely aware of the disconnect between the work we were doing and other factors impacting on learners’ progress. We felt that addressing individual topics such as materials or assessment without addressing the whole system of ELT was bound to have very limited impact. So I was pleased after the first Roadshow to have the opportunity to lead two intensive workshops in Havana, supporting the policy working group set up by Dr Santiago Rivera Peréz from the Ministry of Higher Education.

Policy workshops

The aim of the workshops was to develop an approach to curriculum renewal in the teaching of English in Cuban universities, with a view to achieving exit levels of B1 / B1+ (IELTS 5.5) for graduating students.

The literature on educational change management (e.g. Fullan 1982, 1993; Fullan & Stiegelbauer 1991) strongly suggests that for an educational reform initiative to take root, a systemic approach is essential. In the Cuban university context, this suggested that it would ultimately be unproductive to focus individually and exclusively on teacher training, professional development, teaching materials, learning resources or assessment practices without considering the nexus of interrelationships between all of these factors, what Bowers (1983) refers to as ‘interlocking systems’.

Theory of change

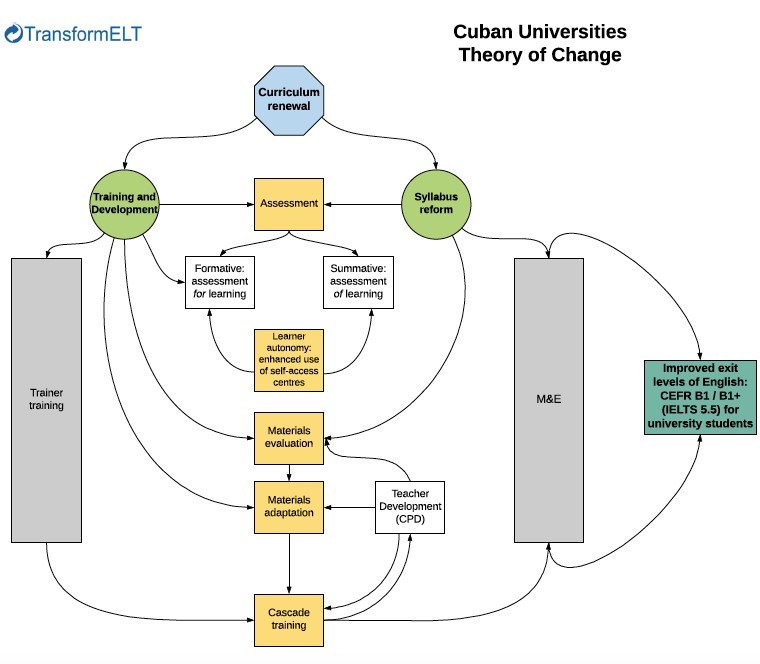

The first workshop in October 2018 developed a theory of change designed to describe the complex set of factors to be taken into account in planning a coherent process of curriculum renewal. This systemic approach is best represented graphically, as a process diagram:

The various interrelationships between the different nodes in the system are described below.

Syllabus reform and teacher training and development

The desired improvement in exit levels for English implied the need for broad-based curriculum renewal, encompassing the need for both syllabus reform and a programme of teacher training and professional development. Investing resources in training teachers without reviewing and revising the syllabus was unlikely to effect deep and sustainable change. Equally, syllabus reform without a coherent programme of teacher training offered little chance of transforming teaching practices. To achieve uptake of a reformed syllabus, there needed to be a programme of training and development designed not only to ensure that teachers have a clear understanding of syllabus goals, but that they are fully equipped with the knowledge and skills required to adapt their current practices and implement the new methods and techniques they need to enable students to attain the required learning outcomes, and crucially, to achieve the desired exit level.

Syllabus reform and assessment

The role of assessment is paramount, as there is inevitably a washback effect of assessment on teaching and learning (Taylor 2005). Summative tests, understandably, have a direct influence on learners’ attitudes and teachers’ practices. And however carefully the syllabus is calibrated to learning outcomes, if the mode and content of summative tests are not adjusted to reflect a revised syllabus, teachers will be under great pressure from all stakeholders to ‘teach to the exam’, even though the exam, if it is not revised, no longer matches the reformed syllabus.

Teacher training and assessment

All language assessment is designed to gather information about learners’ knowledge of language and their ability to do things with language. Since assessment invariably exerts a powerful influence on teaching and learning, it is imperative that teachers be made fully aware of changes made to modes of summative assessment (assessment of learning) in end-of-year and final exams. But it is also important for teachers to broaden their view of assessment, and to integrate formative assessment (assessment for learning) into their classroom practice (OECD 2008). This is informal, ongoing assessment that forms an integral part of classroom practice, that may involve learners in the assessment process (Tomlinson 2005), that is drawn from work that students are doing in the classroom, and that rather than a ‘snapshot’ of what learners can do on a single occasion, provides both teacher and learners with a longitudinal record of progress over time. A portfolio approach is a highly effective way of ensuring maximum student involvement in formative assessment (Romova and Andrew 2015).

Assessment and learner autonomy

An approach to assessment that valorises formative assessment also has important implications for the role that learners themselves can play. Equipped with suitable instruments for self-assessment (e.g. CEFR ‘can do’ statements), students can be fully involved in goal setting, tracking their own progress and collaborating with their teachers in identifying suitable activities to address their individual needs and support further development. In the Cuban university context, much greater use could be made of existing self-access centres, with teachers providing guidance and supplementary practice materials to address particular needs.

Syllabus reform and the coursebook

In any teaching context, there is always a risk that the coursebook becomes a de facto syllabus, and in the Cuban context, where resources are limited and a particular series of coursebooks has been adopted, this risk may be exacerbated. A rational approach to the challenge of shaping the syllabus to ensure that it is more congruent with curriculum goals is to identify and analyse the knowledge and skills required by learners to reach B1 / B1+ and then to reverse engineer the syllabus so as to produce a programme of learning that will take learners to that level. Such a programme can then be mapped against the coursebook to verify the extent to which it matches the syllabus and identify any areas that are insufficient, or lacking entirely.

Teacher training and materials development

To fulfil the goals of the revised syllabus, as well as upskilling in terms of classroom practice, a teacher training programme needs to encompass approaches to materials development. Given constraints with regard to the availability of materials, teachers need to acquire skills in both evaluating and adapting the published materials they are working with. Evaluation implies the need for teachers to interrogate course materials from a critical perspective, in order to identify the extent to which those materials favour the attainment of curricular goals, and the gaps they may identify between what the materials provide and what their learners need. The prerequisites for this process are a clear appreciation of the revised syllabus goals and a critical apparatus to conduct a robust evaluation (for example checklists see McGrath 2002). Having identified those areas where course materials may be insufficient, or lacking entirely, teachers will then need to apply the results of their evaluation. They will require the confidence and the practical skills to adapt materials in ways that match their learners’ specific needs (Islam & Mares 2003). The teacher’s interventions may include:

- extending given material so as to provide more practice

- modifying or supplementing some elements of the material to make it more context-appropriate

- introducing a greater degree of challenge or support

- replacing the material altogether in cases where it is deemed inappropriate or inadequate.

As with formative assessment procedures, learners may also be involved as collaborators in this process (Clarke 1989).

Teacher training and professional development

While a teacher training programme may address the knowledge and skills required to ensure the effective implementation of a reformed syllabus, it is unlikely to be sufficient in itself without teachers developing a local culture of CPD. This may involve a wide spectrum of teacher-led practices, from informal initiatives (e.g. individual action planning, self-help discussion groups, professional reading groups etc.) to more formal, structured approaches such as classroom investigation and action research (Head & Taylor 1997; Hopkins 2014). In contrast to teacher training, which is likely to be compulsory, time-bound and product-oriented, CPD should be voluntary, ongoing and process-oriented, a means of teachers examining and developing their own practice. The essential quality of CPD is that it needs to be teacher-inspired and teacher-directed, and not perceived by practitioners as imposed by academic management – although it can be guided and to some extent co-opted by academic managers to complement a training programme.

Curriculum renewal and cascade training

A cost-effective method for dissemination of teacher training is to employ a cascade model, whereby training is received by a cohort of master trainers, who then go on to replicate the training, delivering training sessions to colleagues. An obvious risk in a cascade model, however, is that the trainers may simply adopt a transmission mode and in so doing unintentionally dilute the effect of the training, with content becoming less and less substantial as it is disseminated.

In a case study of a cascade programme for teachers in Sri Lanka, Hayes (2000) suggests an approach to cascade training designed to avoid such dilution by encouraging active participation, and not expecting “rigid adherence to prescribed ways of working”. He continues: “…it is a basic tenet that development strategies must promote a sense of ownership in teachers and trainers of the programmes in which they are involved and the centres through which they operate”. Hayes goes on to propose a set of basic principles, three of which should be highlighted:

- Normative re-educative models of training: Teachers examine the principles underlying classroom or workshop activities, evaluate the effectiveness of their existing practice, and use this heightened awareness as a basis for modifying that practice.

- Reflexivity: Trainer training exemplifies models of training, and in the same way training exemplifies models of classroom instruction.

- Classroom-centredness: Training is informed by theory, but firmly located in classroom practice.

Action planning

The main thrust of the 2018 workshop was to devise a policy that took into consideration the systemic nature of educational change and that would not attempt to address any single component of the system without attending to its impact on the others. It was agreed that one major implication of this approach was the overriding need for a consolidated action plan, which formed the basis for a follow-up workshop in October 2019. A key development had been the development of new English curriculum documents aligned to Levels A1, A2 and B1 of the CEFR, which provided a vital backdrop to work on integrating the components illustrated above.

Objectives and programme content

To achieve its intended impact, the process of educational change depends on the following criteria:

- Teachers are well prepared for the change.

- There is sufficient time in the curriculum for the change to be accomplished.

- Teaching-learning approaches and materials are appropriate to the revised curriculum.

- Adequate time is allowed for the preparation of new materials.

- Appropriate and timely in-service training is given to teachers in the use of the materials and teaching-learning approaches.

- Teachers receive adequate in-house advisory support as they implement the curriculum.

- Appropriate evaluation procedures are in place to evaluate the effectiveness of the change.

- Adequate material and human resources are available to implement all of the above.

Thus, our main objective was to formulate a combined action plan that would enable the policy working group to implement a coherent programme of interventions to serve the goal of achieving B1 exit levels for graduates by 2022. The workshop focused on identifying SMART objectives and practical procedures in three key areas: teacher training, assessment and materials / resources.

Core principles and key questions

In its general guidelines for curriculum reform, the Ministry of Higher Education had identified multiple challenges in terms of teaching and learning, availability of resources, teacher training and CPD. Accordingly, we identified three core principles informing the new curriculum to form an essential set of guidelines for action planning, viz. that learning should be:

- Student-centred

- Task-based / Project-based

- Content-driven

Detailed discussion centred on a numberof key questions arising out of the Ministry’s general guidelines, with three sub-groups tasked with drafting action plans for these strategic priorities:

- Teacher training / CPD – Teacher ‘buy-in’ is an essential prerequisite for the successful implementation of curriculum renewal. Teacher training must lie at the heart of the reform process, but has to be linked to parallel developments in terms of content and assessment.

- Materials and Resources – Work done within the ELT Roadshows has to some extent raised teachers’ awareness of the options open to them for evaluating, exploiting and adapting published materials, while university self-access centres provide a potentially rich resource to complement teaching and learning in the classroom. This third aspect needs to be developed in harmony with teacher training and assessment to develop a change model that is effective and robust.

- Assessment – Assessment needs to be congruent with the thrust of the curriculum and teacher training. The work done with Prof. Claudia Harsch (University of Bremen) on assessment has evidently brought a great deal of practical awareness to the team, which has provided a sound foundation for this major priority.

Planning for success

An iterative process of peer editing and redrafting was accomplished through successive editorial rounds, with members of each group circulating to read and suggest modifications to the other groups’ draft plans.

The Teacher Training group produced an outline of a nationwide teacher training programme, including specifications of objectives, actions, success criteria, progression milestones, monitoring and evaluation instruments and processes, and responsibilities for each stage of the process. The group acknowledged a number of potential risks in relation to selection of materials, stakeholder commitment, and university management, and proposed appropriate mitigation strategies.

The Materials and Resources group planned to conduct surveys and interviews identify to identify universities’ needs and determine the financial resources required to meet those needs.

The Assessment plan included recommendations for:

- a national research project

- an iterative process of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) to track stakeholder response to the implementation of new assessment practices

- cascade trainer training and rater training

- a series of workshops for teachers to cascade new approaches to assessment, supported by M&E processes for impact assessment

- the introduction of portfolio assessment as the principal method of formative assessment into curriculum guidelines and monitoring implementation

- monitoring the implementation of revised syllabuses aligned to the CEFR

- piloting new high-stakes testing instruments

- reviewing and finalizing rating scales

- validating test specifications and rating scales against the CEFR

On the final day the three sub-groups had the opportunity to revise and refine their action plans and develop timelines. With reference to Kirkpatrick’s (1998) 4-level model (Reaction, Learning, Behaviour, Results), particular emphasis had been placed on the importance for a complex, multi-dimensional project to ensure that M&E processes were fully integrated throughout, that evaluation was not prioritised over monitoring, and that “the opportunity to use monitoring data to take action during the lifetime of the development process” (Markee 1996) was not neglected.

Finally, the following risks were highlighted:

- Poorly thought through monitoring can generate too much data to be efficiently processed, or the wrong kind of data to make useful decisions.

- Unsystematic data collection can lead to biased representations of the project / inaccurate reporting of teacher development needs.

- Little or no monitoring prevents learning from taking place and decreases the likelihood of current and future success.

Conclusion

In developing their action plans and the resultant timelines, the groups took full account of these key considerations and produced practical, actionable plans. It was gratifying to see how much progress had been achieved since the initial workshop in 2018 in terms of participants’ awareness of relevant issues and the development of the new curriculum guidelines. The group worked energetically to produce practical and hopefully feasible action plans for advancing this ambitious project. My first visit to Cuba was in the mid-90s to attend the GELI teachers’ conference. I was immediately excited and inspired by the energy and creativity of a teaching community severely constrained by the effects of the US embargo (known in Cuba as the blockade). One memorable example was the development of an entire English for Science and Technology course built around technThe relaxation of the embargo under Obama was short-lived, and Cubans are again struggling with shortages of essential goods and facilities.

Two memorable examples were a teachers’ newsletter printed out painstakingly on an old dot-matrix printer and the development of an entire English for Science and Technology course built around techno- thrillers left behind in tourist hotels (Diaz-Santos 2000). Sadly, the relaxation of the embargo under President Obama was short-lived, and Cubans are again struggling with shortages of essential goods and facilities. But the inventiveness and professional determination of the Cuban ELT community persists, and it has been an enormous pleasure to be able to make a small contribution to their current enterprise.

References

Bowers, R. 1983. “Project planning and performance”. In Brumfit (ed.) Language Teaching Projects for the Third World. ELT Documents 116. London: BritishCouncil / Oxford: Pergamon Press. Retrieved from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Y299%20ELT-09-screen_0_Language-Teaching-Projects.pdf

Clarke, D. 1989. “Materials adaptation: Why leave it all to the teacher?” ELT Journal 43.2: 133-141.

Diaz-Santos, G. (2000) "Technothrillers and English for science and technology” English for Specific Purposes 19(3): 221–236

Fullan, M. 1982. The meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fullan, M. G. 1993. The complexity of the change process. In Change Forces: Probing the depth of educational reform. pp. 19-41. London: Falmer Press.

Fullan, M., & Stiegelbauer, S. 1991. The new meaning of educational change. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press / London: Casell.

Hayes, D. 2000. “Cascade training and teachers’ professional development”. ELT Journal 54/2: 135-145

Head, K. & Taylor, P. 1997. Readings in Teacher Development. Oxford: Macmillan.

Hopkins, D. 2014. A Teacher’s Guide to Classroom Research. 5th ed. London: Open University Press.

Islam, C. & C. Mares. 2003. “Adapting classroom materials”. In Tomlinson, B. (ed.) Developing Materials for Language Teaching. London: Continuum.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1998. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, 2nd Edition. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

McGrath, I. 2002. Materials Evaluation and Design for Language Teaching. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Markee, N. 1996. Managing Curricular Innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD/CERI International Conference. Learning in the 21st Century: Research,

Innovation and Policy. 2008. “Assessment for Learning / Formative Assessment”. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/site/educeri21st/40600533.pdf

Romova, Z. and Andrew, M. 2015. Embedding learning for future and imagined

communities in portfolio assessment. Unitec ePress Research Report Series (4). Retrieved from http://www.unitec.ac.nz/epress/

Taylor, L. 2005. “Washback and impact”. ELT Journal 59/2 154-155.

Tomlinson, B. 2005. “Testing to learn: a personal view of language testing”. ELT Journal 59/1 39-46.

TPRS, a Valid Procedure in the TEFL Classroom

José Alberto Peña Almora, CubaTeaching Adults a Foreign Language: A Rewarding or a Helpless Task?

Juan Luis Hernández Pino, CubaEnglish as Means or Medium of Instruction (EMI) Within the Policy to Improve English in Cuban Universities Framework. A Case Study at Pinar del Río University

Rubén Alejandro Pérez Gutiérrez, Cuba;Tamara Gutiérrez Baffil, CubaMaking the Pieces Fit - ELT Curriculum Renewal in Cuban Universities

Alan Pulverness, UKAn Analysis of Parallel Forms of the English Language Entrance Test

Daniel Lawrence Schneiter, Czech Republic;Pavel Svoboda, Czech Republic